“What I think is quite clear is that we can work together in the last analysis. And that what has been going on with the United States over the period of the last 3 years- the divisions, the violence, the disenchantment with our society… whether it’s between blacks and whites, between the poor and the more affluent, or between age groups or over the war in Vietnam — that we can start to work together again. We are a great country, an unselfish country and a compassionate country. And I intend to make that my basis for running.”

— Robert F. Kennedy’s final speech, June 5, 1968

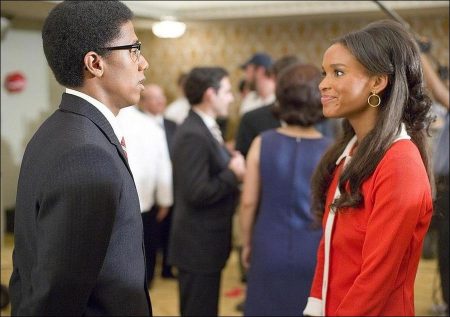

“Bobby” re-imagines one of the most explosively tragic nights in American history. By following the stories of 22 fictional characters in the Ambassador Hotel on the fateful eve that Presidential hopeful Senator Robert F. Kennedy was shot, writer/director Emilio Estevez and an accomplished ensemble cast forge an intimate mosaic of an America careening towards a moment of shattering change – as different characters navigate prejudice, injustice, chaos and their own complicated personal lives, while seeking the last glimmering signs of hope in Kennedy’s idealism. In exploring the diverse experiences of ordinary people, the film celebrates the spirit of an extraordinary man and servers as a snapshot of this emblematic time in history.

Deftly combining fact, fiction and fate, the interwoven human stories of “Bobby” unfold on June 4th, 1968. The film begins its imaginative and stirring re-creation of that catalytic day just a few hours before Kennedy’s assassination, as party-goers, performers, hotel employees and campaigners all descend on the hotel in preparation for the big night.

They include the Ambassador’s retired doorman (Anthony Hopkins) who can’t seem to leave his old haunt behind and plays chess in the grand lobby with fellow retiree Nelson (Harry Belafonte); the hotel’s current manager, Paul Ebbers (William H. Macy), a kindhearted but flawed businessman whose wife Miriam (Sharon Stone) is the hotel’s hairdresser; the stifled hotel switchboard operator Angela (Heather Graham) who hopes her affair with Ebbers will lead to a promotion, to the dismay of her co-worker Patricia (Joy Bryant); the hotel’s kitchen workers, including the bigoted boss Timmons (Christian Slater), learned sous chef Edward Robinson (Laurence Fishburne); Latino workers Jose (Freddy Rodriguez), who would rather be watching the night’s pivotal Dodgers baseball game, and Miguel (Jacob Vargas); and the coffee shop waitress Susan (Mary Elizabeth Winstead), newly arrived from Ohio and hoping to become a big star.

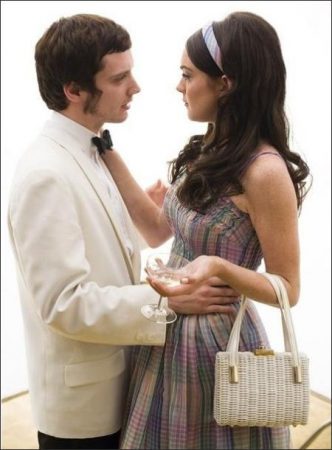

Meanwhile, the hotel’s many guests include the alcoholic singer Virginia Fallon (Demi Moore), who is scheduled to introduce the Senator at his California Primary party, and her frustrated husband Tim (Emilio Estevez); a young bride-to-be (Lindsay Lohan) who is about to marry a young man (Elijah Wood) to save him from going to Vietnam; and his younger wife (Helen Hunt) who are in California on a strained second honeymoon.

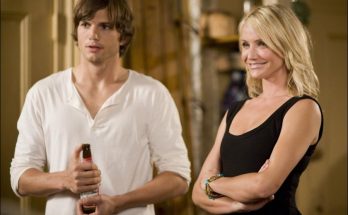

Also gathered in the Ambassador are Kennedy campaign followers including devoted young aides Wade and Dwayne (Joshua Jackson and Nick Cannon); persistent Czech journalist Lenka (Svetlana Metkina); and novice volunteers Jimmy and Cooper (Brian Geraghty and Shia Lebeouf) whose day of campaigning is radically changed when they run into a drug dealer (Ashton Kutcher) who initiates them into the infamous acid trip experience.

As the day progresses, each of these characters will encounter their own battles between the sexes, between races, between social classes, between personal despair and public hope as they all converge on the ballroom for Kennedy’s speech, never to be the same again.

Creating the world of the 1960s-era Ambassador Hotel is a behind the scenes team that includes director of photography Michael Barrett (“Goal!,” “Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang”) production designer Patti Podesta (“Memento,” “Annapolis”), Academy Award-nominated costume designer Julie Weiss (“Frida,” “American Beauty”) and Academy Award-winning editor Richard Chew (“Star Wars,” “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest”).

The day Bobby Kennedy won the California Primary on his way to likely becoming the next President of the United States is one that still haunts America. It was a time not unlike our own – a time of war and fierce divisions – and in an America tearing at the seams, Kennedy was the sole candidate who seemed able to unite people of differing races, classes and beliefs. Having lost his own brother to unthinkable bloodshed, he had publicly transformed into an impassioned, yet pragmatic, advocate for creating a new American future – one that would look beyond rhetoric for credible ideas to end poverty, racism, injustice and, most of all, the growing epidemic of violence. A champion of the underdog, and a man compared to such magical cultural avatars as Dylan and the Beatles, Kennedy was a politician who crossed into territory never entered by a politician before or since.

But Bobby’s vision for what might have been possible never got the chance to be explored. Instead, he was gunned down, along with five others, shortly after midnight in the kitchen of the Ambassador, moments after giving his moving victory speech, only to collapse in the arms of a Mexican busboy. Shot in the head at close range, Kennedy would die at age 42 a day later. The other five victims survived. Despite all the shocks that had come before – the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King (who was killed just 2 months before Bobby), the agonizing violence of the Vietnam War and the protests at home – Bobby Kennedy’s death felt to millions of Americans like the ultimate knockout blow to American idealism. It left many wondering, and still waiting, for a time when that kind of hope and belief in a better America might return.

“Bobby Begins”

“If a single man plant himself on his convictions and then abide, the huge world will come round to him.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson in a favorite quotation of Robert F. Kennedy

In many ways writer / director Emilio Estevez feels he was fated to make “Bobby” all of his life. Just six years old when Robert F. Kennedy died, Estevez vividly remembers that night through a child’s eyes — seeing the horrific announcement that the Senator had been shot on television, and rushing to awaken his father, actor Martin Sheen, a long-time Kennedy supporter, with the shocking news. Soon after that, Sheen took his son to visit the spot where Kennedy had delivered his final speech, a heartfelt, impromptu call for American unity and action in the face of escalating rifts and violence, in the Ambassador Hotel. “I remember my dad holding my hand as we wandered through those grand halls and I remembered my father talking about what we had lost,” recalls Estevez.

Years later that loss would continue to weigh heavily on Estevez. Like many, he began to see RFK’s assassination as the shot that had stopped in its tracks the idealism and optimism of an earlier generation of Americans – and ushered in today’s much harsher world of cynicism, apathy and disenfranchisement. Kennedy’s legacy of refusing to be silent in the face of injustice, of advocacy for the downtrodden and of speaking plainly about what he believed was wrong in America seemed to have far too few successors. “From that moment of June 5, 1968 on, it seemed we became more and more cynical and resigned, and I think it’s a big part of why we are where we are at culturally today,” says Estevez. “It’s heartbreaking ”.

Meanwhile, Estevez had developed into a promising writer/director who was in search of that one special project that would take him to creative places he’d never been. While conducting a photo shoot in the Ambassador Hotel, Estevez was suddenly reeling with memories from that trip with his father and inspiration struck – he decided he would start writing about the night that Kennedy had been assassinated. “All I knew in the beginning is that I wanted to tell a story that would celebrate the spirit of Bobby”, explains Estevez.

Rather than attempt to hunt down all the people who were in the Ambassador that night to request their life rights, Estevez decided to take a novel approach – he would merge the basic facts of the evening with his own imagination. Turning the story completely inside out, he chose to focus not on Kennedy and his convicted assassin Sirhan Sirhan’s movements, which are widely covered in myriad books and documentaries, but instead on a widely varied group of ordinary people whose lives were profoundly changed in those few terrible moments. He began to weave a web of diverse characters, each of whom brings their own individual struggle into that catalytic night in June, as events build, conversation by conversation, to the piercing moment of change. He would use the hotel as a microcosm of what was happening in the country at that time.

Right from the start, the project felt like the most meaningful of Estevez’s life – but he had no idea that this would be the beginning of an intense, years-long journey and fight to get his film made. “So much of what happened in the making of this film was random, so much was coincidence and accidental, and yet nothing was random and nothing was coincidental,” he remarks.

After developing a case of what Estevez calls “paralyzing writer’s block,” he set the script aside. But then came another twist of fate. Estevez set out to re-tackle the screenplay in a remote hotel on the Central California Coast, near Pismo Beach. When he checked in, the woman at the desk recognized him and asked what he was doing there. “I’m writing a script about the night Bobby Kennedy was killed,” he told her. Tears instantly welled in her eyes. “I was there,” she replied.

Estevez interviewed the woman, who had been a Kennedy volunteer in 1968, eventually turning her personal story, which included marrying a young man to keep him out of Vietnam, into the Lindsay Lohan character in the film. “She really helped me crack the spine of the story and give it a beating heart,” he says. “After that, it just started to flow.”

One character strand seemed to lead to the next as Estevez carefully laid out the interwoven stories of the 22 fictional people. They were inspired at once by the spirit of the times and by Estevez’s personal experiences. “I wanted to create characters who would be emblematic of the era and who would really open up the story,” he says. “They are archetypes to a certain degree — but I also know each and every one of these characters intimately. They are all based on people who have been in my life in some way or another.”

Some of the script’s most compelling stories turned out to be those of women – women on the cusp of revelation and change at the very beginnings of the women’s movement, including Demi Moore’s sinking alcoholic singer, Sharon Stone’s stoically betrayed wife, Heather Graham’s ambitious hotel worker and Helen Hunt’s Manhattan socialite. “I think in writing the women characters, my mom was a big influence,” says the writer / director. “She’s a really strong person and I think her voice is in this piece as well.

Estevez completed the screenplay one week before another American tragedy: the events of September 11, 2001. At the time, he chose to keep the screenplay under wraps for another six months, then slowly began to show it to friends and family, receiving lots of enthusiastic responses. But when he tried to get the project off the ground, Estevez was suddenly in the position himself of being a definite underdog. “I had this script that was very large in scope and would obviously be dependent on performances and execution and I hadn’t really proven myself to be that kind of director,” he says. “There wasn’t that kind of trust that I could pull this off.”

But ultimately, over time, the strength of the writing and of Estevez’s passion won out over reservations. Says Producer Michel Litvak, “When I read the script, I knew it was a film we had to make. I believe that the story of Bobby Kennedy belongs not only to the American people, but is an inspiration to all the people of the world. His message and his dream live on.

Once on the set, Estevez revealed that he had the kind of guiding vision that could in fact hold together a star-studded, multi-layered story meshing fact and fiction. “It was madness on the set,” Estevez laughs. “But we made the movie in a real, shoot-from-the-hip, fast-paced, guerilla style that I think suits the subject matter.”

The cast of the film had their own perspective on how Estevez was able to maneuver through so many characters and themes. “He’s just so passionate about what he does,” observes Anthony Hopkins. “He actually lets you do what you want to do and then he comes in with a few suggestions. I think he held complete control of the movie by not trying to over control it.”

For Estevez, a large part of what kept him motivated through the years of fighting to get the film made and then the ultra-fast, high-pressure shoot was simply that he never ran out of inspiration. “Everyone got involved in this film, because we all really care about the things Bobby Kennedy was talking about, and what’s really clear is that the issues he was addressing back then are the same issues we’re facing today. I hope this movie raises the question of why haven’t we moved forward from those times and reveals how relevant Bobby’s ideas still are to us right now.”

22 Characters in Search of RFK

“Some look for scapegoats, others look for conspiracies, but this much is clear: violence breeds violence, repression brings retaliation, and only a cleansing of our whole society can remove this sickness from our soul.” — Robert F. Kennedy, Speech in Ohio, April, 1968

When Emilio Estevez’s screenplay started making the rounds in Hollywood, its themes and his obvious fervor for the project rallied a remarkable ensemble cast to take on the roles of the film’s 22 main characters – each of whom becomes indelibly intense in a very short frame of time. Says co-producer Lisa Niedenthal: “It’s rare that you find a script that has so many incredibly meaty roles in it. Actors were attracted not only by the opportunity to tackle great characters, but to work with their peers on a project that felt so meaningful to all of us.” In a show of loyalty, all of the film’s actors agreed to work for scale.

The very first actor to be cast set the ball in motion: Academy Award winner Anthony Hopkins. Hopkins still has a profoundly strong memory of RFK’s death decades later. “I remember exactly where I was,” he recalls. “I was sitting in a makeup chair in a London studio when the news came through. I said: `They’ve gone insane. The world’s gone mad.’ We had JFK, Malcolm X, Dr. King and now Robert Kennedy. I thought it’s coming apart at the seams. And it was.”

In taking on the role of retired Ambassador doorman John Casey, Hopkins especially relished the opportunity to work in concert with the legendary screen star Harry Belafonte.“It was so wonderful to work with such a distinguished figure from Hollywood history,” says Hopkins about his scenes with Belafonte. “Harry is a dynamic force of nature, a revolutionary force. And the fact that he was so personally close to Bobby Kennedy brought so much more meaning to me.”

Indeed, Belafonte had been preparing to meet with Bobby Kennedy shortly after his life was so cruelly cut short. “I had worked for him, and I had known him for a good spell,” says Belafonte. “Our lives had come together in very unusual and impactful ways.” It was this personal perspective on who Bobby Kennedy was and what he might have meant to the country that compelled Belafonte to take on the role of Nelson. “The moment seen in this film is one which forever changed the course of not only this nation, but one I think changed the course of all human history,” he states.

As for working with Hopkins, Belafonte felt a mutual sense of excitement. “There was not a moment in his presence where I wasn’t being challenged and awakened to great opportunities with just his slightest nuances,” he says.

Having Hopkins as the first member cast in the film became an immediate drawing point for other actors. “He was one of the reasons I took this role,” says William H. Macy, the Academy Award and Golden Globe nominee who plays the hotel’s manager, Paul Ebbers, a man besieged by a raft of personal and professional crises in the course of this one historic day. “I’d act the Yellow Pages with Anthony Hopkins.”

The actors were also pulled into the project by the complexities of their characters. Academy Award and Golden Globe nominee Sharon Stone, who portray Ebbers’ cheated-upon wife, loved the idea of playing a 1960s hairdresser. “I liked the part because I think the beauty salon was really the psychiatrist’s office in the `60s. Everyone comes in to tell her their personal story,” she observes. “I also like the way the script deals with how Miriam is betrayed by her unfaithful husband in a way that feels so true to the times.”

For Stone, there was a feeling on the set of “Bobby” unlike any other film she’s made in her extensive and diverse career. “It was a poetic feeling,” she comments. “To be in the Ambassador and touch those powerful moments and be educated by that time again — it was something very special.”

Many of the cast members also noted the film’s relevance to today’s world – as America faces some of its deepest divisions in decades. “There is still a real need to bring people together,” says Demi Moore. “After Bobby Kennedy was shot there seemed to be a great loss of innocence, and with it came an unfortunate loss of passion and a feeling of helplessness that has endured.”

Moore plays one of the film’s saddest characters, the chanteuse Virginia Fallon, a once glamorous, now drunken lounge singer who has reached rock bottom upon her final performance at the Ambassador. “This was the first time that I’ve had the opportunity to play a woman that drinks way too much,” Moore notes. “It’s exhausting and exhilarating at the same time because you can let go about caring how you look because it’s irrelevant. There’s something very raw about going to a core place and giving your body permission to do anything. There’s no censorship necessary; you can be and say whatever you want.”

Moore especially enjoyed collaborating with her long-time friend Estevez, with whom she worked in his directorial debut, “Wisdom.” “Even though he’s also the writer, he didn’t hold anything as precious,” she comments. “He’s giving but not controlling. He’s especially open to improvisation on the part of actors because he really trusts them. He allowed us to create and share, and at the same time he guided us too.”

Laurence Fishburne, who plays the sous chef with his own ideas about how to deal with a racist society, also has a long past with Estevez. The two have been friends since they were fourteen years old. Yet for Fishburne the power of the screenplay transcended even that. “I just knew that people of all generations would relate to this film,” he says.

For Martin Sheen, Emilio Estevez’s father, the project was a labor of love on many levels. In addition to proudly watching his son come into his own as a director, “Bobby” also continued Sheen’s long-lived relationship with the Kennedy family. The Emmy Award-winning actor previously played Robert Kennedy in “The Missiles of October,” in 1974. In “Bobby” he plays a very different role, that of a wealthy East Coast man who has entered into therapy and is examining the very roots of his modern malaise, much to the discomfort of his younger wife, Samantha, portrayed by Academy Award and Golden Globe winner Helen Hunt.

“Robert Kennedy was a very great personal hero of mine,” Sheen says. “He continues to be a great source of inspiration to me personally. I’m privileged to work for the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Foundation. Each of the last few years I’ve narrated a film that explores the foundation’s involvement in social justice and furthers the work of Robert Kennedy.”

Sheen continues: “I think it’s important for us to celebrate heroes and to try and inspire people to higher and more humane service to their fellow men – and I think this film will do that by honoring the spirit of Robert Francis Kennedy. And that my son has been responsible for this just makes me so hopelessly proud.”

For some of the younger stars, the film was an introduction to the idealism that marked the era preceding the 1968 election. Says star Joshua Jackson, who plays a young Kennedy aide in the film: “The main thing that attracted me to my character was that it seemed so cool to be a true believer without veering off into extremism. Kids who worked for Kennedy were giving everything they had because it was a time before they were disaffected by the political process.”

Hearing Kennedy’s speeches had a profound effect on Elijah Wood, the screen star who came to fore as a heroic Hobbit in “The Lord of The Rings” trilogy and here plays William Avary, a young man about to get married in order to change his draft classification.

“Kennedy’s words are incredibly powerful and really resonated with me,” Wood says, “especially seeing what we are lacking in our world today. Since his death we really haven’t had a political leader that has spoken to so many people, and has provided people with a sense that our country really could turn things around. It’s incredibly sad, actually, when you realize that in a way, when Bobby was shot, the hope of the country was shot, too.”

Others in the cast saw the film as calling out for a new generation to take things in their own fresh direction. “I think that a lot of the things that were going on in ’68 — the Vietnam War, poverty, civil rights — we can draw a direct parallel to what’s going on right now,” says Joy Bryant, the former Yale student and model, who plays hotel switchboard operator Patricia. “I think that we can still take some of those ideals from the `60s, make them more modern. We can’t recapture what happened then. We can’t fully recover from it. But we can move forward.”

Russian actress Svetlana Metkina who stars as the tenacious Czech journalist had another unique point of view, coming from behind what was once the Iron Curtain. She says: “To me, this movie is about more than just a single person. It’s about all of us back then and today. Bobby Kennedy knew how important freedom is for everybody in the world, which meant a lot to someone who grew up in a Communist country.”

Of course not all of the film’s characters have such an inspirational point of view. Christian Slater was challenged by the role of Timmons, the hotel’s kitchen manager who expresses barely contained rage and bigotry towards his largely Hispanic staff. Explains Slater: “Timmons represents the guy who just isn’t thrilled about the idea of change and the direction that Bobby Kennedy wants to move the country in. I think he just comes from a really old school way of thinking, and quite honestly, he’s a bit of a racist.”

Timmons’ wrath comes down especially hard on the kitchen worker Jose Rosas, who can’t believe he has to work a double shift on the night Dodgers pitcher Don Drysdale might extend his amazing, record-setting shutout streak. Jose is played by Freddy Rodriguez, best known for his Emmy-nominated role as an artistically-inclined mortician in HBO’s lauded drama “Six Feet Under.”

Back to the Ambassador

There is yet another character in “Bobby” that plays a major role: the Ambassador Hotel, whose hallways, ballrooms, hair salon, back offices and kitchen connect the characters of the film to one another. It was always clear to Emilio Estevez that the hotel would be a vital location for the film – but unfortunately, just as production was kicking into gear, the hotel where his entire story took place was slated to be demolished.

Once one of Los Angeles’ swankiest spots, the 500-room Ambassador Hotel was built on Wilshire Boulevard in 1921, designed by renowned architect Myron Hunt. It quickly became an integral part of Hollywood’s glamour, hosting such stars of the day as Jean Harlow, John Barrymore and Gloria Swanson. Even more so, the hotel’s famed Coconut Grove Nightclub became a focal point of L.A. nightlife – and in the 30s and 40s, the Ambassador attained fame as the setting of the Academy Awards. It was also renown for regularly hosting US Presidents on their trips to the West Coast.

The Ambassador was still one of Los Angeles’ finest, if fading, hotels in 1968 – when it was irrevocably linked with Robert Kennedy’s death — but by 1989, the deteriorating building was so in need of massive refurbishments that it finally closed its doors. The hotel’s fate was now left to a decade-long series of legal battles. Finally, in 2005, the historic structure was, at last, about to be gutted and transformed into a much-needed Los Angeles school building.

Ironically, at the same time that Estevez was hoping to keep the Ambassador open, his father Martin Sheen was helping the Kennedy family to arrange for its imminent demise. Explains Sheen: “Ethel Kennedy had asked if I would support the family’s effort to have the building torn down — and if a school was built, then hopefully the school would be named after her late husband. So I called several people at the City Council and told them what Mrs. Kennedy wanted. And, coincidentally, Emilio was trying to get them to delay tearing it down so he could film his movie there!”

Fortunately, Estevez was able to wrangle a special dispensation from the Los Angeles Unified School District to film for just one week in the Ambassador before it would disappear forever. During this time, Estevez was able to capture the building’s exteriors as well as its hallway corridors and coffee shop before proceeding with the demolition. “They were literally tearing down the walls around us as we shot!” recalls Estevez. “It’s quite challenging to keep your composure through that.”

The lightning-fast shoot would give the film some of the authenticity Estevez was seeking, but now the creative team was also forced to rethink the film’s design. “The idea had always been to have the camera flow from one room in the Ambassador to the next and have the architecture of the hotel serve as a way of linking all the stories,” Estevez explains. “We never imagined we would have to move from location to location.”

“Our Ambassador Hotel is actually made up of bits and pieces of buildings all over Los Angeles, all put together to give us the flow we wanted,” continues Patti Podesta, the film’s production designer who first came to the fore with her evocative designs of urban paranoia for Christopher Nolan’s innovative thriller “Memento.”

Podesta knew she faced another major challenge in taking on “Bobby.” “It was heavy in that not only was my job to try to capture the essence of the times and that moment in June 1968 but also to capture the Ambassador for probably the last time,” she says. “But researching this kind of stuff and getting to play with it is a designer’s dream.” Podesta focused on using the film’s design to mirror the emotional trajectory of the film. “Everything starts out very bright and frivolous and becomes very sad and tragic – and I tried to use that as a map in terms of making spaces full of texture and with the right sense of light and emotion,” she says.

During the one week the crew had at the Ambassador, Podesta made what she called “emotional sketches” of the building – not so much focused on complete accuracy as on mood and atmosphere. She also pried away as many discarded doors and accessories as she could to add more authenticity to the sets that would later be created elsewhere. (Other furniture items, such as the Ambassador’s authentic lobby chairs, were purchased by the production at an auction held by the School Board.)

Since the building had already been remodeled since 1968, Podesta was further aided in recreating the Ambassador by 20 minutes of raw CBS footage from June 4th that Estevez had come across in his research. In another stroke of serendipity, Podesta also discovered that costume designer Julie Weiss’ sister had been married in the Ambassador in the 60s and had a scrapbook filled with detailed pictures. Additional inspiration came from 60s feature films shot in the Ambassador, including the classic, “The Graduate.”

After scouring the city, a series of Ambassador-like locations were found including the historic Santa Anita Racetrack, which sports a period kitchen and pantry that resemble the Ambassador’s; the 1920’s-era Park Plaza Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard, the elegant, circa-1920s lobby of which was used for the scenes with Anthony Hopkins and Harry Belafonte; the Castle Green Apartments in Pasadena which provided the Ambassador’s lush gardens; and a country club in Agoura, where a few 60s-era cabanas were added to a pool strongly reminiscent of the Ambassador’s. Consistent details wove these disparate spots together into one. “We started to realize that a lot of creating the right look in a hotel has to do with plants and draperies,” laughs Podesta.

The rest of the interiors were built at Santa Clarita Sound Stages, located North of Los Angeles. Here, one of the key sets created was the hair salon where Sharon Stones’ Miriam encounters many of the film’s characters in their most confessional moments. “It’s a little posh and a little Deco – a multi-faceted space where everything plays out in the reflection of mirrors,” says Podesta.

Throughout, Podesta collaborated closely with Academy Award®-winning costume designer Julie Weiss and cinematographer Michael Barrett on palette – utilizing soft, muted colors to give off the effect of a time before film became so vivid and crisp. Her relationship with Estevez, meanwhile, was one built, by necessity, on sheer trust. “The shoot was so fast and we were on such a tight schedule that sometimes Emilio wouldn’t even have seen a set until literally five minutes before he was shooting,” notes Podesta. “But we were so likeminded and he is so articulate in what he wanted that there was a definite trust. We both saw the film the same way: as a kind of intimate series of conversations leading up to one transformational moment.”

All of the artistic crew’s special touches – from the hotel furniture to the Jackie O dresses and bouffant hair-dos –helped the cast and crew to feel even more a part of 1968. That also extended to the film’s photographic style. In working with cinematographer Michael Barrett, Estevez hoped to create a fresh look and feel for the film that would capture the essence of 1968 as the dividing line between an innocent, hopeful society and the troubled, chaotic one we are so familiar with today. “People sometimes make the mistake of seeing 1968 as kind of a walk down Haight-Ashbury, all colorful and psychedelic, but it was really just before all that happened. In 1968, there was still a kind of formality to American life. People still dressed for dinner, they said `please’ and `thank you.’ Young Kennedy supporters, along with those of Eugene McCarthy, even cut their hair before going out to campaign,” Estevez explains. “I wanted to capture that formality.”

But Estevez also wanted to contrast that traditionalism, just as Kennedy had, with an infusion of fierce energy and creativity. “While there is a formality and to the film, the camera never stops moving,” he continues. “Ninety percent of the film was shot on Steadicam to give the film a real free-floating kind of feeling.”

The intensity of the shoot increased as the production approached the scene they all knew would be the hardest, both technically and emotionally: the frenzied shooting in the Ambassador Hotel kitchen. Kennedy had come down from his hotel suite to make his victory speech around 11:30 p.m. When the speech ended at 12:15 a.m., and as the roused audience began chanting “Bobby! Bobby!,” the Senator made his way into the kitchen pantry, a short-cut that led to where the press were waiting outside. In the kitchen, the mood was ecstatic and chaotic as hotel staff and party-goers crowded into the small space hoping to get a closer glimpse of Kennedy. It was then that shots rang out.

Though Estevez was not filming the incident as it had happened -he wanted to authentically capture the sense of sudden madness and helplessness that gripped the room that night. For the cast and crew, it was a powerful experience. “When they were shooting the actual assassination there was an eerie feeling on the set,” explains Jacob Vargas, who plays the kitchen worker Miguel.” “I remember watching some of the playback. It just felt so real. And that made it scary. There was pandemonium, and there were bodies and blood. I wasn’t even born at that time, but it gave me goosebumps.”

For Estevez the scene was vital not only as the film’s dramatic climax but because he hoped it would cut right to the core of Kennedy’s stand against violence. To remind audiences of Kennedy’s alternate vision, Estevez overlaid the scene with one of Robert F. Kennedy’s most beautiful and eerily prescient speeches, given in April 1968, on ways to end violence.

Bobby’s Legacy: The Continuing Impact of Robert F. Kennedy

“Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago – to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.” — Robert F. Kennedy, speaking just after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination

In 1966, three years after his brother, President John F. Kennedy, was killed and two years before his own bid for the Presidency would end in bloodshed and tragedy, Robert F. Kennedy made a speech in South Africa, the words of which have continued to sum up his viewpoint on the world. In the speech, Kennedy concluded: ” Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.” Kennedy’s own life was to become such a ripple of hope, at least for a brief, shining moment.

The third son of Joseph P. Kennedy and the seventh of nine children, Robert F. Kennedy would spend the first part of his life living in his older brother’s shadow. After the death of the eldest Kennedy son, Joe Jr., in 1944, John F. Kennedy became the family’s great hope and it fell to Bobby to support his brother’s political rise.

In 1952, Bobby managed his brother’s campaign for the Senate and would go on in 1960 to help JFK garner the Democratic nomination and eventually win the Presidency of the United States. JFK would then name his brother Attorney General, sparking one of the closest and most intimate relationships between a President and his counsel in American history. Bobby Kennedy was highly visible in the short-lived but dynamic Kennedy administration, playing key roles in the Cuban Missile Crisis and Civil Rights issues. Yet just as the Kennedy administration was beginning to find its rhythm, John F. Kennedy was assassinated, leaving the nation traumatized, and Bobby alone, questioning and nearly inconsolable.

Following his brother’s death, Kennedy underwent a visible change that deeply impacted his own original political vision. The once ruthless crusader seemed to have been made newly raw and vulnerable by suffering and grief – and he began talking about creating a society based on morally sustained action and compassion. He spoke out on in very plain, emotional, human language on a wide range of topics including civil rights, freedom, democracy, poverty, human rights, education, healthcare, war and peace. But he wasn’t simply about words – he also remained very much a man of action, personally going into migrant worker camps, urban ghettos and the Mississippi Delta to see how the poor really lived, meeting with angry African American activists to better understand their concerns, and going out of his way at every turn to speak with the marginalized and disenfranchised. He became a voice for all the Americans who had no voice.

Then, in 1968, with the war in Vietnam escalating along with unrest at home, and Lyndon Johnson’s administration foundering, Kennedy faced a quandary. Though he did not want to run for President in the wake of his brother’s death, he was eventually pulled into the race by the sheer force of millions of ordinary Americans who wanted him to take up their mantle. Kennedy came into the race with a very different platform from any other politician. He not only wanted to end the war in Vietnam, he wanted to uplift the very fabric of the country and reawaken a passionate for making not only the U.S., but the world, a better place. His personal style was also entirely unique – mixing the most radical, creative ideas with core conservative values of self-sacrifice, morality and hard work.

While Democratic rival Eugene McCarthy appealed mainly to a youthful intellectual crowd, Kennedy’s appeal was widespread among both young and old, the wealthy and the blue collar, and across all races. Journalists compared his effect on audiences to that of a rock star. People screamed when they saw him coming and clamored to touch him, as if something about his very presence was magic. Some have theorized that Kennedy spoke in a way that tapped directly into people’s greatest hopes and dreams.

The night that Bobby Kennedy was shot, Kennedy’s vision of a brighter future seemed to have been snuffed out by the rising tide of violence in America. But the story wasn’t over. Kennedy’s legacy has continued to inspire millions who continue to believe in the promise of human creativity and compassion. His work lives on through all those who continue to strive for change, as well as through the Robert Kennedy Memorial, which promotes a peaceful and just world with programs that help the disadvantaged and oppressed, that seek to tackle the toughest problems facing current society.

1968 Timeline

January 21 The bloody, 77-day Siege of Khe Sahn starts in Vietnam, bringing some of the fiercest fighting American forces have yet seen

January 31 The Tet Offensive begins as Viet Cong soldiers seize key strategic and civilian locations and briefly take over the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. Both American and civilian casualties continue to rise alarmingly

February 8 Senator Robert F. Kennedy makes a historic speech saying that the U.S. cannot win the Vietnam War and needs to rethink its policy

February 8 National Guardsmen kill 3 black students and injure nearly 50 in South Carolina during a civil rights protest against a whites-only bowling alley

February 8 Pro-segregation candidate George Wallace enters the race for President

February 18 Beatles George Harrison and John Lennon fly to India to try Transcendental Meditation

February 29 Secretary of Defense Robert MacNamara resigns in the wake of the Tet disaster

March 12 Peace advocate and Democratic candidate for President Eugene McCarthy wins an unexpected 40% of the vote in the New Hampshire Primary, signaling trouble for the incumbent President Lyndon Johnson

March 13 New liberal Czech leader Alexander Dubcek relaxes censorship and begins making democratic reforms for the first time behind the Iron Curtain

March 17 Though the race is already in full swing, Robert F. Kennedy announces his late candidacy for President on an anti-violence platform

March 16 Hundreds of Vietnamese civilians are massacred at My Lai by U.S. troops

March 31 In the wake of the Tet Offensive and given the rising popularity of his rivals, Lyndon Johnson withdraws from the Presidential race with the famous words “I shall not seek and I will not accept the nomination of my party… “

April 4 Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. is assassinated on the balcony of a Memphis hotel, sparking national grief and racial violence in cities nationwide.

April 11 Days after Martin Luther King’s death, President Johnson signs into law the historic Civil Rights Act of 1968

April 23 An 8-day student sit-in takes place at Columbia University. Students protesting links to the Defense Department take over 5 buildings and more than 600 are arrested

April 29 The musical “Hair” opens at the Biltmore Theatre in New York

May 3 The city of Paris, France is shut down for days by massive student riots and worker strikes involving more than 10 million people

May 30 Robert Kennedy loses the Oregon primary to Eugene McCarthy, marking the first time a Kennedy had ever lost an election

June 1 Simon and Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson” hits number one on the charts

June 3 Poor People’s March on Washington takes place

June 3 Artist Andy Warhol is shot in his New York studio, The Factory, by Valerie Solanas. Though seriously wounded, he survives.

June 4 Dodger Don Drysdale pitches his sixth straight shut-out game

June 4 Robert Kennedy wins the California Primary, putting him in prime position to take the Democratic nomination in Chicago

June 5 Shortly after midnight, after making a rousing victory speech in the ballroom of the Ambassador Hotel, Kennedy is shot and mortally wounded. Five others are also shot during the melee, but they all survive. Kennedy remains conscious until the ambulance arrives, asking if everyone else is all right.

June 6 Robert F. Kennedy dies in Good Samaritan Hospital, at the age of 42

August 8 Richard Nixon is nominated for President by the Republican Party

August 20 The Soviets invade Czechoslovakia, crushing its fledgling democratic movement

August 24 France becomes the world’s fifth nuclear power

August 26 The Democratic National Convention in Chicago descends into chaos and violence as thousands take to the street in protests and demonstrations, clashing with police

August 29 The Democratic party nominates Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey for President; Humphrey is nominated without winning a single primary.

November 5 Richard M. Nixon is elected President of the United States.

Bobby (2006)

Directed by: Emilio Estevez

Starring: Anthony Hopkins, Demi Moore, Sharon Stone, Lindsay Lohan, Elijah Wood, William H. Macy, Helen Hunt, Christian Slater, Heather Graham, Freddy Rodriguez

Screenplay by: Emilio Estevez

Production Design by: Patti Podesta

Cinematography by: Michael Barrett

Film Editing by: Richard Chew

Costume Design by: Julie Weiss

Set Decoration by: Lisa Fischer, Anuradha Mehta

Art Direction by: Colin De Rouin

Music by: Mark Isham

MPAA Rating: R for language, drug content and a scene of violence.

Distributed by: MGM, The Weinstein Company

Release Date: November 17, 2006

Visits: 80