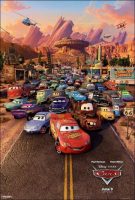

Taglines: Ahhh… it’s got that new movie smell.

“Cars,” the seventh animated feature to be created by Pixar Animation Studios and released by Walt Disney Pictures, is a high octane adventure comedy that features a wide assortment of cars as characters who get their kicks on Route 66.

After taking moviegoers magically into the realm of toys, bugs, monsters, fish, and superheroes, the masterful storytellers and technical wizards at Pixar Animation Studios (“The Incredibles,” “Finding Nemo,” “Monsters, Inc.”), and Academy Award-winning director John Lasseter (“Toy Story,” “Toy Story 2,” “A Bug’s Life”), hit the road with a fast-paced comedy adventure set inside the world of cars.

Lightning McQueen (voice of Owen Wilson), a hotshot rookie race car driven to succeed, discovers that life is about the journey, not the finish line, when he finds himself unexpectedly detoured in the sleepy Route 66 town of Radiator Springs. On route across the country to the big Piston Cup Championship in California to compete against two seasoned pros, McQueen gets to know the town’s offbeat characters –including Sally (a snazzy 2002 Porsche voiced by Bonnie Hunt), Doc Hudson (a 1951 Hudson Hornet with a mysterious past, voiced by Paul Newman), and Mater (a rusty but trusty tow truck voiced by Larry the Cable Guy) – who help him realize that there are more important things than trophies, fame and sponsorship. Fueled with plenty of humor, action, heartfelt drama, and amazing new technical feats, “Cars” is a high octane delight for moviegoers of all ages.

After taking moviegoers magically into the realm of toys, bugs, monsters, fish, and superheroes, the masterful storytellers and technical wizards at Pixar Animation Studios (“The Incredibles,” “Finding Nemo,” “Monsters, Inc.”) and Academy Award-winning director John Lasseter (“Toy Story,” “Toy Story 2,” “A Bug’s Life”), hit the road with a fast-paced comedy adventure set inside the world of cars.

A Pixar Animation Studios film presented by Walt Disney Pictures, “CARS” is a high octane delight for moviegoers of all ages, fueled with plenty of humor, action, heartfelt drama, and amazing new technical feats. Adding to the fun is a driving score and new songs by Oscar-winner Randy Newman, along with original musical performances by such top talents as Sheryl Crow, James Taylor, Brad Paisley, Rascal Flatts, and John Mayer. he film coincides with the celebration of Pixar’s 20th anniversary, and the company’s recent acquisition by Disney.

Lightning McQueen (voiced by Owen Wilson), a hotshot rookie race car driven to succeed, discovers that life is about the journey, not the finish line, when he finds himself unexpectedly detoured in the sleepy Route 66 town of Radiator Springs. En route across the country to the big Piston Cup Championship in California to compete against two seasoned pros, McQueen gets to know the town’s offbeat characters – including Doc Hudson (a 1951 Hudson Hornet with a mysterious past, voiced by screen legend Paul Newman), Sally Carrera (a snazzy 2002 Porsche voiced by Bonnie Hunt), and Mater (a rusty but trusty tow truck voiced by Larry the Cable Guy) – who help him realize that there are more important things than trophies, fame, and sponsorship.

The all-star vocal cast also includes free-wheeling performances by Tony Shalhoub, Michael Keaton, Cheech Marin, George Carlin, Katherine Helmond, and perennial Pixar “good luck charm,” John Ratzenberger. Michael Wallis, author of the critically acclaimed book, Route 66: The Mother Road, and the authority on that legendary American artery that connected north to south, and east to west, is heard in the film as the voice of the Sheriff of Radiator Springs.

Delivering more fun and authenticity to the cast for “CARS” are vocal performances from some of the all-time greatest names from the racing world, including the legendary Richard Petty, plus “drive-on” roles by Mario Andretti, Dale Earnhardt, Jr., Darrell Waltrip (who holds the record for five wins at the NASCAR Coca Cola 600), and Michael Schumacher, the ace German Formula 1 racing legend, who is widely considered to be the best Grand Prix racing driver of all-time.

Veteran Olympic and sports commentator Bob Costas lends his seasoned voice to the character of Bob Cutlass, the colorful host at the film’s racing events. Tom and Ray Magliozzi (aka Click and Clack, the Tappet Brothers), hosts of the popular NPR program, “Car Talk” (first broadcast in Boston in 1977 and picked up nationally ten years later), weigh in as the not-so-coveted sponsors Rusty and Dusty Rust-eze.

Commenting on the characters themselves, Bonnie Hunt (the voice of Sally) says, “When they write these movies at Pixar, they start with the heart of the character first. And once the heart is there, it doesn’t matter what’s on the outside. Even a car becomes a character and a personality. The heart and soul is what turns a steel car into a character and a person. It’s not only the script that makes these films special. John Lasseter and the artists at Pixar provide the imagination that is the gold mine of their storytelling process. Their imaginations go to the fantasies of the heart, and of life, and of our values. Anything that you can possibly visualize in your mind, they bring to life.”

The driving force behind “CARS” is John Lasseter, who returns to directing for the first time since “Toy Story 2” in 1999. During the past seven years, in addition to guiding “CARS” through the production process, Lasseter has executive produced and overseen all of Pixar’s creative endeavors (“Monsters, Inc.,” “Finding Nemo,” and “The Incredibles”), and supervised the building of a new state-of-the-art Studio in Emeryville, California. This latest film tapped into Lasseter’s personal love of cars and racing, as well as a variety of issues that were near and dear to him.

“CARS” was co-directed by Joe Ranft, who also served as story supervisor for the film, and voiced several incidental characters. One of the most gifted and respected story artists in modern day animation, and the congenial voice behind such favorite Pixar characters as Heimlich the ravenous caterpillar (“A Bug’s Life”), Wheezy the penguin (“Toy Story 2”), and Jacques the shrimp (“Finding Nemo”), Ranft passed away in August, 2005. He had collaborated with Lasseter on all three of his previous directing efforts, and had been a key creative force at Pixar for over a decade.

Serving as the film’s producer was Darla K. Anderson, a Pixar veteran whose previous producing credits include “A Bug’s Life” and “Monsters, Inc.” Combining her technical expertise with her tremendous respect and knowledge of the creative process, Anderson guided all aspects of the production and helped support Lasseter’s vision from the start. The film’s associate producer was Tom Porter, a technical pioneer in the world of computer animation who has been part of the Pixar inner circle since its inception. Eben Ostby, another original member of the Pixar team, was the supervising technical director.

The original story for “CARS” was conceived by John Lasseter, Joe Ranft, and Jorgen Klubien. The screenplay for the film was written by Dan Fogelman, Lasseter, Ranft, Kiel Murray and Phil Lorin, and Klubien.

Central to the plot and themes of “CARS” is the iconic Route 66, along which much of the story takes place. Lasseter and his team headed out on the historic highway on several occasions to research and observe the importance and impact of this cultural phenomenon.

Route 66 expert Wallis, who has been exploring the “Mother Road” for over 60 years and who served as guide/pathfinder for the research trips, explains, “Route 66 is a mirror held up to the nation. It reflects what’s going on in the nation at any given time. For most people, this highway is the most famous in the world, and it represents the great American road trip. It’s a chance to drive from Chicago, (the city of big shoulders) through the heartland, and the Southwest, past ribbons of neon, across the great Mojave, to the Pacific shore at Santa Monica. Route 66 is the road the Dust Bowlers took.

During World War II, it was used as a military road by the G.I.s. It’s the road of Bobby Troup and Elvis. It’s the road our fathers, mothers, and grandparents traveled. Everybody at some point in their life in this country, whether they know it or not, has touched that road. It really does have iconic status. It gives motorists an experience that they’re not going to get in the great coastal cities. They have to go out in the middle of that juicy pie and taste it; not just nibble the crust…and really indeed life begins at the off ramp,” concludes Wallis, who co-authored the book, The Art of Cars with his wife, Suzanne Fitzgerald Wallis.

“CARS” represents one of Pixar’s most challenging and ambitious efforts to date. The Studio has successfully and convincingly brought moviegoers into the world of toys, bugs, monsters, fish, and superheroes, but creating a believable and true world inhabited solely by cars was a whole other matter.

Lasseter’s mandate to have the car characters look as real as possible posed some daunting new challenges for Pixar’s technical team. Having a film where the characters are metallic and heavily contoured meant coming up with resourceful ways to accurately show reflections. “CARS” is the first Pixar film to use “ray tracing,” a technique which allows the car stars to credibly reflect their environments.

The addition of reflections in practically every shot of the film added tremendous render time to the project. The average time to render a single frame of film for “CARS” was 17 hours. Even with a sophisticated network of 3000 computers, and state-of-the-art lightning fast processors that operate up to four times faster than they did on “The Incredibles,” it still took many days to render a single second of finished film.

Lasseter also insisted on “truth to materials,” and instructed the animation team not to stretch or squash the cars in ways that would be inconsistent with their heavy metal frames. The animators did a lot of “road testing” to get the characters to behave in a believable and entertaining way, and found ways to add subtle bends and gestures that were true to their construction. The animators also discovered how to use the tires almost as hands to help them with their performance.

Tuning Up the Story

“CARS” was a very personal story for John Lasseter. As a boy growing up in Whittier, California, he loved to visit the Chevrolet dealership where his father was a parts department manager, and got a part-time job there as a stock boy as soon as he turned 16.

According to Lasseter, “I have always loved cars. In one vein, I have Disney blood, and in the other, there’s motor oil. The notion of combining these two great passions in my life – cars and animation – was irresistible. When Joe (Ranft) and I first started talking about this film in 1998, we knew we wanted to do something with cars as characters. Around that same time, we watched a documentary called `Divided Highways,’ which dealt with the interstate highway and how it affected the small towns along the way. We were so moved by it and began thinking about what it must have been like in these small towns that got bypassed. That’s when we started really researching Route 66, but we still hadn’t quite figured out what the story for the film was going to be. I used to travel that highway with my family as a child when we visited our family in St. Louis.”

It was at this point that Lasseter’s wife, Nancy, persuaded him to take a much-needed vacation, during the summer of 2001. Lasseter recalls, “Nancy said to me that if I didn’t slow down and start paying attention to the family, the kids would be going off to college before I knew it and I would be missing a huge part of our family life. And she was right!”

The entire family packed up a motor home, and set out on a two-month trip with the goal of staying off the interstate highways, and dipping their toes in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. “Everybody thought we would be at each others throats the whole time,” adds Lasseter, “but it was the exact opposite. When I came back from the trip, I was closer to my family than ever and I reattached to what was important in life. And I suddenly realized that I knew what the film needed to be about. I discovered that the journey in life is the reward. It’s great to achieve things, but when you do you want to have your family and friends around to help celebrate. Joe loved the idea and our story really took off from there. Our lead car, Lightning McQueen, is focused on being the fastest. He doesn’t care about anything except winning the championship. He was the perfect character to be forced to slow down, the way I had on my motor home trip. For the first time in my professional career I had slowed down, and it was amazing. The unique thing about Pixar films is that the stories come from our hearts. They come from things that are personal to us, and that move us. This gives special emotion and meaning to the films.”

In 2001, Lasseter, Ranft, producer Darla Anderson, production designers Bob Pauley and Bill Cone, along with other key members of the production team flew to Oklahoma City and headed out from there in a caravan of four white Cadillacs on a nine-day trip along Route 66. Historian/author Michael Wallis led the expedition, and introduced them to the people and places that make that road so very special.

At each stop along the way, the team observed firsthand the “patina” of the towns, and tried to capture the richness of textures and colors. Painted advertisements on the sides of buildings, weathered and overlaid, were of particular interest. Careful studies were made of rock and cloud formations, and the variety of vegetation along the way.

Wallis notes, “Every road has a look based on where the road goes. It reflects the territory on both shoulders. The look of Route 66 is everything from the licorice colored soil of Illinois in the land of Lincoln, to the desert sands of the Mojave. It’s the all-American look.”

“On our research trip, we went to the cafes and mom-and-pop shops, and motels along the way. We talked to hitchhikers, cowboys, waitresses and mechanics. We met a lot of interesting characters along the way. If you’re a real road warrior and you know the old highway, you will be pleased, because the film is going to remind you of places and people you might know on the Mother Road.”

Out on the Texas Panhandle, just west of Amarillo, is an unusual site named Cadillac Ranch, where an eccentric Texan commissioned three artists collectively known as “Ant Farm” to create site-specific art work on his ranch. They buried a row of Cadillacs as a monument to the rise and fall of the tailfin, and Pixar has paid homage to that landmark in `CARS.’”

Truth to Materials

John Lasseter had some very specific words for the designers, modelers, and animators who were responsible for creating the film’s car stars: “Truth to materials.” Starting with pencil and paper designs from production designer Bob Pauley, and continuing through the modeling, articulation, and shading of the characters, and finally into animation, the production team worked hard to have the car characters remain true to their origins.

Characters department manager Jay Ward explains, “John didn’t want the cars to seem clay-like or mushy. He insisted on truth to materials. This was a huge thing for him. He told us that steel needs to feel like steel. Glass should feel like glass. These cars need to feel heavy. They weigh three or four thousand pounds. When they move around, they need to have that feel. They shouldn’t appear light or overly bouncy to the point where the audience might see them as rubber toys.”

According to directing animator James Ford Murphy, “Originally, the car models were built so they could basically do anything. John kept reminding us that these characters are made of metal and they weigh several thousand pounds. They can’t stretch. He showed us examples of very loose animation to illustrate what not to do.”

With the limitations of movement imposed by the metal frames, the animators had to be inventive and resourceful to create the wide range of movement and expression required for the story.

Directing animator Bobby Podesta observes, “The really cool thing about cars is that they could be a lot of different things. They can move like a car when they’re driving around. But we could make them appear almost animal-like at times, and have them gesture or do something that humans can do, while staying true to car materials. For example, there’s a scene where Mater creeps across a tractor field, and he’s suddenly like a lion in Africa sneaking up on his prey. You find yourself relating to the car in a different way.”

The Look of “Cars”

From the thrilling opening nighttime race, to the dusty, faded facades of Radiator Springs’ Main Street, and revving up to a climax with the action-packed daytime race in California, Pixar’s production designers and artistic team went into overdrive to capture the diverse moods and settings of “CARS” in a stylish way.

A great believer in research and first-hand experience, Lasseter took his key creative team on a road trip along Route 66 in 2001 to help them prepare for their assignment. Nine people, nine days, four white Cadillacs. For good measure, Route 66 expert Michael Wallis led the expedition and provided a running narrative via walky-talkies along the way.

Production designer Bob Pauley, a Detroit native and lifetime car enthusiast, who oversaw the design of the car characters and the two racetrack environments, recalls, “Michael told us at the very start of the trip, `you don’t know what’s going to happen out there. All sorts of new things and experiences are going to happen, and you just have to roll with it and enjoy it, and be open to it.’ And it was true. Typically, we’d go into a town, and we’d hear all these wonderful stories from the locals. We’d soak it all in while getting a haircut at the barbershop, or enjoying a sno-cone, or taking the challenge to eat a 72-ounce steak at the Big Texan. We even took soil samples. It was unbelievable – purple, red, orange, ochre. So many wonderful colors!

“One of the most meaningful moments for all of us occurred at a stop somewhere in Arizona,” continues Pauley. “We were on the side of a road close to the big highway. It was a beautiful road that wound perfectly around the environment. It turns and goes right through this gorgeous butte. As we were sitting there, a truck pulled up with an older Native American and his grandchild. He asked us `How do you like our land?’ We told him how beautiful it was, and he told us that he was out here when they blasted the cutaway for the big highway through his ancestor’s sacred land. It was a powerful moment being there on a road that works so well with the environment, and seeing the interstate that slices through it without any care or respect at all. It was amazing to hear these great stories first-hand from a person whose family had been there for generations.”

Associate producer Tom Porter recalls, “When John and his team came back from their Route 66 trip, there was a lot of talk about wanting to capture the patina of the Southwest. They wanted everything in the film to be shaded so that it had the authenticity of that old 40s, 50s, 60s stuff that was faded and weathered after fifty years. John wanted the full complexity of a Southwestern town looking authentic, and then a similar set of challenges in the racing world.”

Bill Cone, the production designer who was responsible for creating the look of the film’s environments and building a five-mile stretch of road that leads in and out of the town of Radiator Springs, recalls, “I think of the style for this film as cartoon realism. You have talking cars, so you’ve already taken a step away from reality in that regard. The forms are a little whimsical. You’ll see these car shapes on the cliffs, and the clouds are stylized. I reached the conclusion that humans in a human universe would see their own forms in nature, which they often do. They name things like Indian Head Rock. So, in a car universe, they would have car-based metaphors for forms. Suddenly, you could see these cliffs that looked very much like the hoods of cars, or an ornament. Great American artists like Maynard Dixon also had a big influence on us with their landscapes of the Southwest and the clouds that they painted.”

Sophie Vincelette, sets supervisor for the film, was responsible for creating the film’s mountain range that pays homage to the famous Cadillacs planted in the ground along Route 66. Other mountains are shaped like wheelwells, and bumpers.

In every aspect, “CARS” represents a new level of attention to detail for Pixar. With its crumbly bits of concrete, accumulated dust, and layers of faded advertisements painted on brick walls, Radiator Springs feels like a real place audiences could visit.

According to Vincelette, “Our challenge was to give the buildings in town the appearance of having a sense of history. We worked closely with the shading and modeling teams to give them a weathered look, and to make sure that things were not always straight. There are weeds growing out of cracks in the cement on the sidewalk.”

Adding to the authenticity of the desert location, modelers in the Sets department were able to dot the landscape with thousands of pieces of vegetation, including cactus, sagebrush (in brown, green, yellow and tan varieties), and grass. Rocks of varying formations also added interest to the scenery.

To ensure authenticity in their car designs, the production design team conducted research at auto shows, spent time in Detroit with auto designers and manufacturers, went to car races, and made extensive studies of car materials.

“Research is a big thing for John,” says Pauley. “It’s also the most fun part of the job because we got to go to car shows and races, and other neat stuff. One of the things we did was to visit Manuel’s Body Shop right near the Studio. He gave us a lot of detail and helped us understand how they apply layers and coats of paint on a car.”

Characters shading supervisor Thomas Jordan explains, “Chrome and car paint were our two main challenges on this film. We started out by learning as much as we could. At the local body shop, we watched them paint a car, and we saw the way they mixed the paint and applied the various coats.

“We tried to dissect what goes into the real paint and recreated it in the computer,” he continues. “We figured out that we needed a base paint, which is where the color comes from, and the clearcoat, which provides the reflection. We were then able to add in things like metallic flake to give it a glittery sparkle, a pearlescent quality the might change color depending on the angle, and even a layer of pin-striping for characters like Ramone.”

Shading art director Tia Krater adds, “While we were at Manuel’s one day we found this old beat-up chrome bumper and we asked if we could have it. He started to clean it up, and we said `No! No! Don’t clean it!’ It was exactly what we were looking for. We loved how dirty it was and the patina. It had a little bit of everything we were looking for – pitting, scratches, milky blurriness, rust, and blistering. All in one bumper! One of our technical guys, who ended up shading Mater, took it out in the sun, and spent a lot of time staring at it and taking lots of pictures to analyze the textures and surfaces.”

Pixar’s Shining Achievements

Over the past 20 years, Pixar Animation Studios has pushed the limits of computer-animation to exciting new heights, and continued to harness the medium to showcase their stories and characters in exciting new ways. From their earliest Oscar-winning and nominated short films to the industry’s first full-length CG feature, “Toy Story,” Pixar has never been content to rest on their laurels. Each film has challenged them in new ways whether it was the blades of grass and crowd scenes in “A Bug’s Life,” the caricatured-but-realistic humans in “Toy Story 2,” the hairy characters and simulated clothing of “Monsters, Inc.,” the vibrant underwater world of “Finding Nemo,” or the action-packed environments and human characters in “The Incredibles.” Their latest undertaking, “CARS,” posed some of the greatest challenges to date.

Under the supervision of associate producer Tom Porter, supervising technical director Eben Ostby, and Pixar’s resident group of technical wizards, “CARS” got off to a fast start and scored some impressive achievements along the way.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for the “CARS” technical team was creating the metallic and painted surfaces of the car characters, and the reflections that those surfaces generate. An algorithmic rendering technique known as “ray tracing” was used for the first time at Pixar to give the filmmakers the look and effect that they wanted.

Ostby explains, “Given that the stars of our film are made of metal, John had a real desire to see realistic reflections, and more beautiful lighting than we’ve seen in any of our previous films. In the past, we’ve mostly used environment maps and other matte-based technology to cheat reflections, but for `CARS’ we added a ray-tracing capability to our existing Renderman program to raise the bar for Pixar.”

Ray tracing has been around for many years, but it was up to Pixar’s rendering team to introduce it into nearly every shot in “CARS.” Rendering lead Jessica McMackin was responsible for rendering the film’s final images, while rendering optimization lead Tony Apodaca had to figure out how to minimize the rendering time.

McMackin notes, “In addition to creating accurate reflections, we used ray tracing to achieve other effects. We were able to use this approach to create accurate shadows, like when there are multiple light sources and you want to get a feathering of shadows at the edges. Or occlusion, which is the absence of ambient light between two surfaces, like a crease in a shirt. A fourth use is irradiance. An example of this would be if you had a piece of red paper and held it up to a white wall, the light would be colored by the paper and cast a red glow on the wall.”

“Our computers are now a thousand times faster than they were on `Toy Story,’” adds Apodaca, “but even though they’re faster, our appetites have gotten bigger and we challenge ourselves more. Because of ray tracing and all the reflections, the average time to render a single frame of film on `CARS’ was seventeen hours. Some frames took as much as a week. On this film, we’ve made larger and more beautiful images with more subtle lighting and ray tracing.”

Among the film’s other major accomplishments is a ground-locking system that kept the car firmly planted on the road, unless the story called for some exception to this rule. Characters supervisor Tim Milliron, who managed the group in charge of modeling, rigging and shading the characters, wrote the code for this program.

“The ground-locking system is one of the things I’m most proud of on this film,” says Milliron. “In the past, characters have never known about their environment in any way. A simulation pass was required if you wanted to make something like that happen. On `CARS,’ this system is built into the models themselves, and as you move the car around, the vehicle sticks to the ground. It was one of those things that we do at Pixar where we knew going in that it had to be done, but we had no idea how to do it.”

Another major accomplishment for the Characters team was to come up with a universal rig that would work for practically every character. This means the same animation controls (or avars) could be applied to each of the nearly 100 unique car characters without creating new articulation components. The same basic chassis was also fitted to the geometry of each individual car, but the suspension was customized for each vehicle.

“We topped out at around 1200 avars that the animators would touch,” explains Milliron. “Some characters, like Mater with his tow rig, obviously had more. More than ever, the avars were designed to work together. For example, there are four big avars for the mouth. There’s an avar that moves the mouth to the left, and to the right, something that moves the corner of the mouth up and down, a jaw up-down avar, and an avar that moves the corner of the mouth in and out.”

Milliron’s group was also responsible for the crowds of cars that inhabit the stands at the film’s opening and ending race sequences. With 120,000 cars in the stands, and an additional 2000 in the infield, this easily qualifies as the biggest crowd scenes ever done at Pixar (far surpassing the milling ants in “A Bug’s Life”). Complicating the situation, all of the vehicles in this crowd have some animation on them.

To help capture the thrills and excitement of the film’s racing scenes, Jeremy Lasky, the director of photography responsible for camera and layout, and his team visited many car races, and had extensive talks with the camera experts who photographed such events. Veteran Fox Sports director Artie Kemper, a pioneer in televising car races, proved to be a great source of information.

According to Lasky, “Artie gave us really great notes about where he would typically place his cameras on the track. He also talked about shots that he wished he could get. We were able to do a lot of things that were impossible for him to do. We could put a camera under the car, place one on the middle of the track, set up a crane shot that comes down and have the cars race right over the top of the cameras. Artie told us that he wished he had those toys. The camera placement in `CARS’ allowed us to put the audiences right in the middle of the excitement. We put them into a world they were familiar with, and then we hit them with shots that they’ve never seen. The film has these spectacular moments where the cars are ripping two millimeters past the camera lens, which is impossible in live-action, and we set it up for them to believe it’s possible.”

Even in the more calm and serene setting of Radiator Springs, some impressive achievements were accomplished. One of the film’s most stellar and complex moments occurs at the end of Act II, where the neon lights are turned on again, as the town is revitalized and a parade of cars cruise down Main Street. With its bright, bold, brilliant lights coming from numerous sources and accompanying reflections, this sequence proved to be enormously complicated but one of the film’s most rewarding and luminous moments.

To enhance the richness and beauty of the desert landscapes surrounding Radiator Springs, the filmmakers created a department responsible for matte paintings and sky flats. Technical director Lisa Forsell and her team worked their magic in this area.

“Digital matte paintings are a way to get a lot of visual complexity without necessarily having to build complex geometry, and write complex shaders,” says Forsell. “We spent a lot time working on the clouds and their different formations. They tend to be on several layers and they move relative to each other. The clouds do in fact have some character and personality. The notion was that just as people see themselves in the clouds, cars see various car-shaped clouds. It’s subtle, but there are definitely some that are shaped like a sedan. And if you look closely, you’ll see some that look like tire treads.

“The fact that so much attention is put on the skies speaks to the visual level of the film,” she adds. “Is there a story point? Not really. There is no pixel on the screen that does not have an extraordinary level of scrutiny and care applied to it. There is nothing that is just throw-away.”

Steve May, the effects supervisor for “CARS” brought that same level of scrutiny to nearly ½ of the film’s 2000 shots. Among the numerous effects created for the film were dust clouds trailing behind cars, tire tracks, skid marks, water, smoke, and drool (from Mater’s front end).

Cars (2006)

Directed by: John Lasseter

Starring: Paul Newman, Richard Petty, Owen Wilson, Bonnie Hunt, Dan Whitney, John Ratzenberger, Larry the Cable Guy, Cheech Marin, Jenifer Lewis, Katherine Helmond, Tony Shalhoub

Screenplay by: John Lasseter

Production Design by: William Cone, Bob Pauley

Cinematography by: Jeremy Lasky

Film Editing by: Ken Schretzmann

Music by: Randy Newman

MPAA Rating: G for general audience.

Distributed by: Buena Vista Pictures

Release Date: June 9, 2006

Visits: 54