Taglines: He’s not lean. He’s not mean. He’s nacho average hero.

Nacho (Jack Black) is a man without skills. After growing up in a Mexican monastery, he is now a grown man and the monastery’s cook, but doesn’t seem to fit in. Nacho cares deeply for the orphans he feeds, but his food is terrible – mostly, if you ask him, a result of his terrible ingredients. He realizes he must hatch a plan to make money to buy better food for “the young orphans, who have nothing” (…and if in doing so Nacho can impress the lovely Sister Encarnación, that would be a big plus).

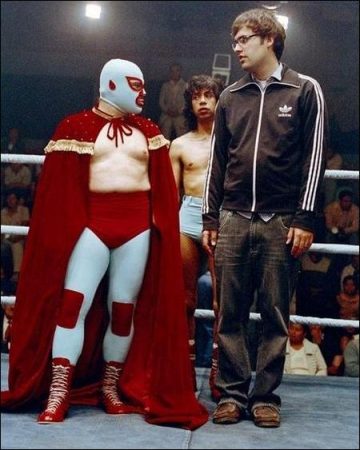

When Nacho is struck by the idea to earn money as a Lucha Libre wrestler, he finds that he has a natural, raw talent for wrestling. As he teams with his rail-thin, unconventional partner, Esqueleto (the Skeleton), Nacho feels for the first time in his life that he has something to fight for and a place where he belongs.

As Lucha is strictly forbidden by the church elders at the monastery, Nacho is forced to lead a double life. Disguised by a sky blue mask, Nacho conceals his true identity as he takes on Mexico’s most famous wrestlers and takes on a hilarious quest to make life a little sweeter at the orphanage.

“Before we made `Nacho Libre,’ I was really scared,” says Jack Black, who takes on his most eccentric and wildly comedic role to date. “I was thinking, `Oh man, what if I don’t pull it off? What if I get hurt? Holy crap, do I have to wear one of those super-tight unitard bottoms? Tights?! I’d rather be naked!’ But, you know what? That’s when it’s funny. When I’ve been really embarrassed and scared, that’s when things have turned out to be really good.”

About the Production

Black takes on the role of Nacho, a cook in a Mexican orphanage searching for his place in the world. The chance to work with director Jared Hess, whose first feature film was the independent smash hit “Napoleon Dynamite,” attracted the actor-producer to the project. “I loved `Napoleon Dynamite,’” says Black.

“Mike White and I were both excited by the the thought of working with him.” After speaking to Hess about an idea for a Lucha Libre wrestling picture, Black was in. “I told him, `If you’re at the helm, dude, I’m gonna suit up, because I wanna party with you.’”

Hess says he suspected Black’s excitement from the onset: “I think when Jack first heard about the idea that he’d be able to throw down in some tights and a cape, it was very appealing to him.”

“I don’t want to brag, but I’ve been told that I’m a natural luchador wrestler,” says Black. “I had the moves from the very beginning. Everyone asked me, `Did you study these moves?’ And I said, `No, why? Am I kick-ass?’ And they said, `You’re kick-ass.’ I think I have some inborn skills and I think maybe Jared sensed that and that’s why he wanted me to do this. I know he was thinking, `I would love to see J.B. throw down some hardcore, Lucha-style wrestling.’ It was meant to be.”

The film was written by Jared Hess & Jerusha Hess & Mike White, the last of whom is Jack Black’s producing partner at their newly formed production company Black & White Films and the writer of “The School of Rock.” “Nacho is a poor little orphan kid who’s stuck in a monastery, gets shoved into this life, and is never really accepted by the brothers in his church,” says Jerusha Hess. “They don’t respect him. He’s always felt a little put upon; when he decides to become a luchador, something awakens in him.”

From the very beginning, it was clear that only one man had the kick-ass comic skills, the boundless energy, and the physical build to bring Nacho to life. “In our first meeting with Jared, he said that he and Jack Black had already been talking and wanted to do a project together,” says producer Julia Pistor. “We thought if you put Jack Black in a mask, he’d still have such expression with just his eyes and eyebrows, it would be great and very funny. It all fit together perfectly.”

White, who co-wrote the film and serves as a producer, says that the filmmakers were motivated by the combination of elements that inspired the movie, from the true story that served as a jumping-off point to the classic Lucha Libre films with the immensely popular Luchadore, Santo. “Even though I wasn’t a Lucha Libre expert when we started, in retrospect, it all seems inevitable,” he says. “First, this story – which is inspired by a true story – of a guy who cooks for friars and orphans by day and wrestles by night felt like such movie material. Later, the more old Santo movies we saw, the more matches we went to, the more we saw that this was a colorful, comic world and how much fun it would be to have Jack as a huge centerpiece to it.”

Hess and the producers were confident Black could handle the Lucha ring. “Aside from being one of the best physical comedians, he’s actually also an incredibly agile and energetic man,” says Pistor. “If you’ve ever seen him singing and performing in Tenacious D, he’s all over the stage, doing acrobatics and crazy jumps. We knew he would be able to deliver the physical comedy and stunts.”

While it was clear that only Jack Black could play the lead role as the filmmakers envisioned it, they were also sensitive to the fact that they were telling a Mexican story with an Anglo in the lead. They were careful to write the role specifically for Black.

“Nacho’s mom was a Scandinavian missionary and his dad was a Mexican deacon. They tried to convert each other, but got married instead,” says White. “When they died, he grew up as an orphan. Even though he’s grown up, he’s still there, the fun guy among all the humorless, disciplinarian monks. He’s the buddy that these kids need in their lives.”

Black says that living and working in Mexico was the key to picking up the accent. “I pulled a Meryl Streep,” he says. “I worked hard to perfect my accent. I wanted it to be kick-ass, but it was not easy.”

In fact, Black jokes that his audible guideline for his accent came from the cinema. “I would think of Ricardo Montalban, especially his performance in `The Wrath of Khan,’” says Black. “I’m not trying to do an impersonation – it’s just something that I would think of for inspiration. I love Ricardo Montalban – he’s so dramatic!”

Kidding aside, White points out that Black came to the production prepared. “Jack speaks a lot of Spanish,” he says. “When he came down to Mexico, he quickly picked it up again, and he came to the first day of rehearsal with a fully born take on the accent.”

De la Reguera was impressed with Black’s accent and discipline. “He’s very professional,” she says. “Jack’s always thinking about the character. Because he has to have a Mexican accent, he’s very concentrated and focused all the time. Sometimes, I gave him tips that he imitated.”

“That guy´s a triple threat,” Hess says of Black’s comedic, athletic, and acting skills. “He´s a total genius. He´s very funny, a team player who has no ego and working with him is great. Everybody on the crew just felt like they could totally approach him. He was just such a fun, funny, happy-go-lucky guy.”

Pistor says that the scene in which Nacho’s secret is revealed shows off Black’s amazing acting range. “Jack’s depth and ability as a comedian and an actor are best shown in the fire scene,” says the producer. “As Nacho prays for God’s blessing on his upcoming wrestling match, his robe catches fire. After running out of the church and rolling on the ground, extinguishing the flames, Nacho’s robe has burned off from the bottom up, revealing his wrestling tights. It’s a hysterical image Jack’s standing there exposed to everyone. But, he then goes and delivers a speech that is so moving and so meaningful, it brings tears to your eyes. It’s a remarkable scene because it shows Jack as a funny, physical comedian, on fire, wearing a funny outfit, to a heartfelt speech about defeating Ramses and taking care of the orphans, all in one shot.”

Pistor found irresistible the idea of a guy who cooks for priests and orphans by day and wrestles at night. “I was drawn in by the incongruity of it all,” she says, and underlines that the first person that she and her team at Nickelodeon Movies thought of to direct the unique and funny story was “Napoleon Dynamite” creator Jared Hess. “We found `Napoleon Dynamite’ to be full of a lot of heart and we believed he was perfect for this story.”

“The idea just struck Jared as being so hilarious, he felt we could do this,” says Jerusha Hess. “My first impression of Lucha Libre was that it’s a funny mix of acrobatics, the circus, and the pro wrestling we know in America. It was funny and different from American wrestling.”

“It just hit me as something so strange and wild – it was a story I wanted to tell,” says Jared Hess. “The concept is so outrageous that it seemed like the perfect follow-up to `Napoleon.’”

“Jared’s got a mind for incredible, strange stories,” says Black. “He’s drawn to interesting, peculiar characters and people. And he’s populated the whole film with them. Every face is another amazing: `Whoa! Look at that guy!’ Everyone’s got a really funny, awkward story. That’s what I love about `Napoleon Dynamite’ and about this film, too.”

Part comedy, part drama, part high-flying wrestling action, “Nacho Libre” springs from the lively spectacle-sport it showcases, relying on Lucha Libre’s reality and myth, organic truths and fantastic creations. “No one’s ever seen a movie like this before,” says Black. “It’s hilarious, sweet, and totally unique.”

The colorful, bizarre, surreal world of Lucha Libre boasts a long history of legendary wrestlers with superhero names – El Santo, Blue Demon, Gory Guerrero, Tarzan Lopez, Superbarrio Gomez – and, in Mexico, the sport enjoys a popularity second only to soccer. During its Golden Age, from the late 1930s through the early 1980s, Lucha Libre dominated Mexican pop culture with its burlesque mix of costumed wrestlers, including women and midgets.

“Lucha Libre transcends the generations in Mexico,” says White. “There’ll be little kids, there’ll be old women jumping up and yelling, `Kill him! Kill him!’ Lucha brings the whole community together in ways that pro wrestling in the states doesn’t.”

Stories of luchadores rising from modest and impoverished beginnings, fighting their way to fame feeds the sport’s working-class mythology, symbolic pageantry, and accessibility. Throughout Mexico, at outdoor rings or arenas, in gyms and auditoriums, fans watch battles between tecnicos and rudos (“good guys,” “bad guys”), a morality play in the square circle, with self-styled gladiators seeking body slams and soap operatic salvation. An ostentatious mix of entertainment, athleticism and cathartic ritual, the world of Lucha Libre is both a diversion and an avocation for its fans of all ages and incomes.

“I’ve always been a fan of the Lucha Libre movies by Santo, who was kind of the Muhammad Ali of the Mexican wrestling world,” says “Nacho Libre” co-writer-director Jared Hess. “I was first exposed to the sport through the films of Santo, who made a number of really cool movies in the sixties and seventies. When the opportunity presented itself to do a film about the whole Lucha Libre world, I was really excited.”

Lucha Libre differs from American-style wrestling in its secret identities and must-see-live experience. “There´s something so mysterious and unique about Lucha Libre, comparing it to other forms of wrestling in the world,” says Jared Hess. “Luchadores wear masks to hide their identities and are very protective about that. I don´t think there was ever a photograph taken of Santo with his mask off. The other thing is Lucha Libre is something that you need to experience live. You need to see how quickly the fight moves from in the ring to the audience. It is something very unique to Lucha Libre: you need to be there.”

Lucha Libre lives large in Mexico and has a growing popularity in the United States via live shows such as Lucha VaVoom, which tours the country and regularly appears in Las Vegas. While some luchadores are chiseled to perfection, the lure and magic of Lucha Libre is the idea of the Lucha as the “every man.” With his true identity concealed under a mask, a luchador acts out for the masses, sending symbols of evil, corruption, and power crashing to the mat.

Nothing disgraces a luchador more than being unmasked in the ring. A fighter will do anything to protect his mask, and consequently, his identity. “A luchador never, never, ever takes off his mask. No one ever sees their faces. I don’t know if their wives do,” laughs de la Reguera. “If they take off your mask, you lose. You lose everything.”

Julia Pistor says that the combination of Jack Black, Jared Hess, and the weird world of Lucha Libre wrestling make the picture irresistible. “What is so great about `Nacho Libre’ is it doesn’t fit into any one box,” says Pistor. “It’s funny, bizarre, left-of-center, colorful, beautiful, and exciting.”

“We always intended to create a world you’ve never seen before and bring an original comic sensibility to it,” says White. “Our goal was a comedy with broad appeal, but with a unique filmmaker’s voice.”

Filming in Mexico

One cornerstone of the film’s development was to film in Mexico with a local crew and a largely Mexican cast. “When we first spoke to Jared, we all agreed that we didn’t want re-create luchadores in America,” says Pistor. “We were committed to shooting the movie in Mexico. There’s an incredible film community down there and we were excited at what we could do.”

“Because we were able to shoot the entire film in Mexico, it’s very real,” says Jerusha Hess. “These are real people that you could never find in Hollywood. Everyone on the cast and crew was so excited about the movie, because it’s about showing the world their culture.”

One advantage that kept the production running smoothly is that the director speaks fluent Spanish, allowing him to communicate directly with his crew and cast. “From the first day we met, Jared spoke to me in perfect Spanish,” says de la Reguera. “Because he knows the language, and has lived in Venezuela and spent months in Mexico, he knows perfectly how we live. He knows the difference between Venezolanos, Colombianos, Argentinians, Mexicans. He was very respectful; that was so important.”

The film’s primary location was in the state of Oaxaca, located in southern Mexico. For thousands of years, Oaxaca’s extensive mountain systems (some 10,000-feet above sea level), tropical rain forests, deserts, and coastal lowlands created a geographic isolation, allowing indigenous cultures to flourish.

“It definitely helps to be immersed in the culture that you’re portraying in the movie,” says Black. “Oaxaca is gorgeous. It has ancient pyramids, amazing architecture, and a rich flavor that adds to the whole experience. I don’t think there’s ever been a comedy with as many beautiful backdrops before as we have in this film.”

“Jared chose Oaxaca on gut,” says White. “It showcased Mexico’s mountains and Mexican culture – it was a magical place. We had a charmed experience filming there.”

“Oaxaca is one of Mexico’s most beautiful places and one of our best-kept places,” says de la Reguera. “The indigenous people who live in Oaxaca are very intelligent and strong. We in Mexico are very proud of Oaxaca and the artisan traditions they keep.”

The region’s distinctive traditions and languages (approximately fifteen indigenous languages are still spoken today, including Zapotec, Mixtec, Mixe, etc.) have created a rich, complex cultural diversity unmatched in other portions of Mexico or Latin America. These co-existing civilizations, some dating back thousands of years, have produced generations of artisans, including entire villages that devote themselves to producing specific goods and handicrafts. Oaxaca is widely known for its world-class cuisine, its chocolate, chiles and moles, as well as its black pottery, ceramics, wood carvings, metalworks, textiles, basketry and stone work.

“In choosing a location, we were looking for finding a balance between the two worlds of the monastery and the Lucha Libre,” says the director. “Oaxaca fit perfectly into what we were looking for.”

Hess and his team found their monastery in Etla, an ancient town about 40 minutes in a valley outside downtown Oaxaca. The long-abandoned ex-convent Etla had the variety of rooms necessary to serve alternatively as interiors of the monastery and orphanage. Across the fields of Etla, on a sloping hilltop near the ex-convent, is the Santuario del Senor de Las Penitas, where an old church served as the exterior for the monastery. Production designer Gideon Ponte and his crew partially reconstructed the existing church belltower and extended the building with a multi-story faux stone facade to create the compound where Nacho and the orphans live.

Nacho Libre (2006)

Directed by: Jared Hess

Starring: Jack Black, Ana de la Reguera, Héctor Jimenez, Richard Montoya, Peter Stormare, Diego Eduardo Gomez, Moises Arias, Cesar Gonzalez, Rafael Montalvo, Carla Jimenez

Screenplay by: Jared Hess, Jerusha Hess, Mike White

Production Design by: Gideon Ponte

Cinematography by: Xavier Grobet

Film Editing by: Billy Weber

Costume Design by: Graciela Mazón

Set Decoration by: Beauchamp Fontaine, Maria Paz Gonzalez

Art Direction by: Hania Robledo

Music by: Danny Elfman

MPAA Rating: PG for rough action, and crude humor including dialogue.

Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: June 16, 2006

Visits: 85