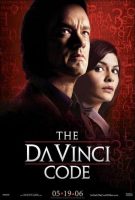

Taglines: Seek The Truth.

Famed symbologist Professor Robert Langdon (Tom Hanks) is called to the Louvre museum one night where a curator has been murdered, leaving behind a mysterious trail of symbols and clues. With his own survival at stake, Langdon, aided by the police cryptologist Sophie Neveu (Audrey Tautou), unveils a series of stunning secrets hidden in the works of Leonardo Da Vinci, all leading to a covert society dedicated to guarding an ancient secret that has remained hidden for 2000 years. The pair set off on a thrilling quest through Paris, London and Scotland, collecting clues as they desperately attempt to crack the code and reveal secrets that will shake the very foundations of mankind.

The Da Vinci Code is a 2006 American mystery thriller film directed by Ron Howard, written by Akiva Goldsman, and based on Dan Brown’s 2003 best-selling novel of the same name. The first in the Robert Langdon film series, the film stars Tom Hanks, Audrey Tautou, Sir Ian McKellen, Alfred Molina, Jürgen Prochnow, Jean Reno, and Paul Bettany.

The film, like the book, was considered controversial. It was met with especially harsh criticism by the Roman Catholic Church for the accusation that it is behind a two-thousand-year-old cover-up concerning what the Holy Grail really is and the concept that Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalene were married and that the union produced a daughter.

Many members urged the laity to boycott the film. Two organizations, the Priory of Sion and Opus Dei figure prominently in the story. In the book, Dan Brown claims that the Priory of Sion and “…all descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents and secret rituals in this novel are accurate”. The film grossed $224 million in its worldwide opening weekend and a total of $758 million worldwide, becoming the second highest-grossing film of 2006 behind Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest. It was followed by two sequels, Angels & Demons (2009) and Inferno (2016).

The Genesis of The Da Vinci Code

The phenomenal success of Dan Brown’s novel, The Da Vinci Code, was just beginning to invade the public consciousness when producer John Calley was encouraged to read the book by Sony Chairman Howard Stringer. “I was crazed by it, fascinated. It was a first-rate thriller,” Calley recalls. He immediately optioned the film rights.

At the same time, Imagine Entertainment co-chairman Brian Grazer and his partner, director and producer Ron Howard, were also keen on adapting the book for the screen. Grazer was especially intrigued by some of its underlying issues: “Not only did I like The Da Vinci Code as an entertaining and exciting read, but there were certain profound things about the story that caught my attention. There were questions of history versus the creation of history – questions I found exciting and compelling.”

When Grazer and Howard learned that Calley had already optioned the rights, they approached him with their ideas about a movie version of The Da Vinci Code, and a partnership was formed. Howard’s wife was reading the book with her book group when he mentioned that he might direct a film version, and was delighted that their reactions were all glowing. He says: “I discovered the book more or less the way the whole world did – through amazing word-of-mouth. People are interested in it for different reasons and are personally impacted by it in a variety of ways.”

But the main reason he was eager to direct The Da Vinci Code has to do with his love of the adventure thriller genre. “This story has all the style and traditional suspense elements that make a movie work as an entertaining narrative,” says Howard. “It takes the viewer along with the confidence that it’s headed in a particular direction but then surprises you in so many ways. That’s why the story Dan Brown created so captivated his readers. It feels familiar as a mystery and as a thriller but then, wow, there’s this fascinating turn of events.”

Calley was glad to hear of Howard’s interest in The Da Vinci Code, having long searched for the right opportunity to work with the Oscar-winning director. “I’ve always admired Ron,” says Calley. “He’s skillful and moderate in the best sense, in that he never has an agenda. He was a great choice for this project, since he brings a kind of fundamental intelligence that is totally appropriate to the material.

Having previously collaborated with screenwriter Akiva Goldsman on A Beautiful Mind and Cinderella Man, Howard felt he was the natural choice to adapt Dan Brown’s book. “It was a pretty daunting task,” says Howard. “By the time we’d all decided to make it into a movie, the book had gone from being a big hit to being this historic success story. I’d already been working very closely with Akiva and he and I had some fairly deep conversations about the novel, because it’s more than just believing it would make a good movie story. In choosing to take it to the screen you also have to ask yourself a lot of the questions that the book poses to the reader. I’ve never really been involved in a film project like this, one that not only generates feeling and emotion and is entertaining, but also really stimulates great conversation.”

Goldsman himself says he was a bit daunted by the task of adapting Brown’s best-selling literary phenomenon to the screen, since so many people had read it and had visualized it in their own minds. “I was tremendously impressed by the book and had absolutely no idea how to adapt it, since it’s such a complex, labyrinthine and intricate piece of fiction,” Goldsman confesses. “My inclination was to shy away from it. But then I sat down with Ron, and he had such a clear idea of what he wanted to do with it that he turned me around and gave me the confidence to try.”

Two-time Academy Award winner Tom Hanks, who embodies Dan Brown’s protagonist Robert Langdon in the film, also acknowledges the challenges in trying to adapt such a successful book for the big screen: “You have to give every reader what they’re expecting, because, quite frankly, the book is really good,” says Hanks. “You could change it, make it different, but you’d better be sure you’re also making it better. Akiva’s job in adapting something that is as specific as The Da Vinci Code is a monumental task, because of all of his great instincts as a screenwriter as to what makes for a good cinematic narrative.”

The filmmakers frequently conferred with Brown during the writing of the adaptation. “Dan made himself accessible in the most understanding, collaborative kind of way, in terms of his acceptance of the fact that, of course, the screenplay was not going to be a verbatim version of the novel,” remembers Howard. “He knew we were going to have to streamline it somewhat. But he was a really important resource in helping us interpret things he had learned or read including several things he discovered after he wrote the book, which have found their way.”

The Cast and the Characters

After Goldsman’s screenplay was completed, the next major hurdle for the filmmakers was to assemble a cast that would embody the essence of the fascinating personalities that populate Brown’s novel and could translate to the screen as engaging and entertaining characters in their own right.

As executive producer Todd Hallowell sees it: “This is a unique film in that it has a truly international cast. Watching Ron slowly piece together all the right elements so that they perfectly meshed was a pretty amazing process. He really put together an extraordinary ensemble.

Tom Hanks / Robert Langdon

“Robert Langdon is the thinking man’s hero, someone who is on a relentless quest to unravel this mystery,” observes screenwriter Goldsman. “Throughout history, we have been drawn to people who seek out the truth, who search for the grail. They were often knights, men who were pure of heart, strong of spirit and unrelenting.”

Hanks had been involved with The Da Vinci Code almost from its inception. Though he and Howard had not collaborated in the past several years, they remained close. “It was more than friendship that led me to want to cast Tom as Robert Langdon,” says Howard. “When I started talking to him about the role, I had a similar kind of positive feeling I had when we first discussed Apollo 13 a decade ago. There was a natural intersection between Tom as an actor and a person and the sensibility of the character of Robert Langdon. He’s this guy to a tee. Langdon is driven by curiosity and has a wonderfully dry sense of humor. More than anything else, Langdon is fascinated by details and eager to understand the truth. Tom is also very smart and fascinated by the world around him. In casting Tom, I was certain I had brought in a really intelligent and helpful collaborator.”

Hanks was eager to work with Howard again, particularly since he was taking on the challenge of playing a character so different from anything in his own life experience. “Langdon has this arcane knowledge that is very deep and quite extensive and he is fascinated by it,” says Hanks. “He has somehow turned this knowledge into a lucrative career. As a symbologist, he can tell you what three marks on a cave wall represent, what they meant then and how they’ve come to be interpreted down through the ages. This is a guy who is continuously observing absolutely everything. He sees all these connections, all the time.”

The actor says his collaboration with Howard was essential in his process of discovering the character of Robert Langdon: “Ron is so easy-going. At the same time he’s incredibly responsible, creatively vigilant and dedicated to excellence.”

Two-time Academy Award winner Tom Hanks, who embodies Dan Brown’s protagonist Robert Langdon in the film, also acknowledges the challenges in trying to adapt such a successful book for the big screen: “You have to give every reader what they’re expecting, because, quite frankly, the book is really good,” says Hanks. “You could change it, make it different, but you’d better be sure you’re also making it better. Akiva’s job in adapting something that is as specific as The Da Vinci Code is a monumental task, because of all of his great instincts as a screenwriter as to what makes for a good cinematic narrative.”

The filmmakers frequently conferred with Brown during the writing of the adaptation. “Dan made himself accessible in the most understanding, collaborative kind of way, in terms of his acceptance of the fact that, of course, the screenplay was not going to be a verbatim version of the novel,” remembers Howard. “He knew we were going to have to streamline it somewhat. But he was a really important resource in helping us interpret things he had learned or read including several things he discovered after he wrote the book, which have found their way into the script. So, our movie is in some ways a kind of an updated, annotated version of The Da Vinci Code.”

Jean Reno / Bezu Fache

The name Bézu is the location of a Knights Templar fortress in Southern France, and Fache means “cross” in French.

Jean Reno had previously worked with producer John Calley and was very interested in the role of Bézu Fache because he was fascinated by the idea of playing a character who is disappointed when his trust in Aringarosa is betrayed.

“He’s involved in this because he truly believes in something,” Reno explains. “But first and foremost, he’s a cop and he’s trying to do his job. I was interested in exploring the idea of how my character would react when he’s betrayed by an Archbishop.”

Howard says there’s nobody better in his mind to play the French police captain than Reno. “Jean is one of those spirits that just brings a lot of joy to the process, as well as intelligence, great taste and talent.”

In portraying Bézu Fache, Reno was stepping into a role that was tailor-made for him as well, he explains: “It was quite an honor when I found out that Dan Brown said he wrote the character with me in mind. It made playing him in the film even more meaningful to me.”

Alfred Molina / Bishop Aringarosa

The bishop’s name is one of the most intriguing in Brown’s novel. Aringa meaning “herring” and Rosa means “red.” Does this mean the Bishop is a red herring?

Alfred Molina was cast while he was in production on As You Like It, which costars Howard’s daughter, Bryce Dallas Howard. He dashed to London from the location where he was shooting in another part of England for a read-through and a day of rehearsal. Molina says the opportunity to spend time with Howard and screenwriter Goldsman prior to production was invaluable. “Ron, Akiva and I sat in a room going over all the scenes I was in with a fine-tooth comb, fine tuning all the different points that we wanted to bring out and talking about how best to tell the story in terms of what my character was doing, “ he explains.

Howard appreciated the attention Molina lavished on his role in order to plumb the inner depths of his character. “Alfred understood the character and the culture he comes from in ways that were far more sophisticated and authentic than is actually written. That extra level of truth found its way into his character and onto the screen.”

The Look of The Da Vinci Code

The Da Vinci Code filmed at a number of locations throughout Europe and at Pinewood and Shepperton Studios, where several sets were built. Although the production did shoot at the Louvre in Paris, it was essential to rebuild the Grand Galerie in a studio so that a majority of the action could unfold in a more controlled environment, and away from the masterpieces at the actual museum.

To this end, production designer Allan Cameron constructed sections of the museum on the “James Bond” stage at Pinewood Studios just outside of London. “I knew from the very beginning that we were going to build a small part of the Louvre on a stage,” Cameron says. “But when we went to the Louvre, we were worried about damaging the floors, as well as any of the priceless paintings.

After a couple of visits to Paris, we decided to build even more of the museum on the stages at Pinewood, which from my point of view was much more fun than shooting on location. My scenic artist, James Gemmill, had to paint 150 paintings that required careful measurement at the real Louvre. We even had marble samples created to match the marbles around the skirtings and around the windows. Finally, floor boarding was constructed by my carpenter using wood veneers to approximate the floor in the Grand Galerie. They were then photographed and printed onto plastic sheets and laid on the floor.”

Cameron explains that all the paintings that were reproduced were digitally photographed, then blown up and painted over, sometimes projected on the wall and painted by Gemmill. “James painted them all like the original paintings. He knows all about glazes and crackle techniques. So the actual surface of the paintings looks pretty realistic.”

Adds James Gemmill (Head Scenic Artist) on the texture of the painting reproductions that he created: “I tried to pay attention to all the textures of the paintings. We can’t paint using the exact techniques, but the textures are important. That’s the difference between looking at a movie and seeing a painting on a wall and realizing that it’s a print rather than a painting. When the light is reflected off it, you can see the texture, so it’s important to get it right.”

A number of other sets were also built at Shepperton Studios in the southwest of London, including the interior of Saint-Sulpice and a number of rooms inside Château Villette, where Leigh Teabing resides. “We wanted to use the real château in the story and we were lucky enough to get permission to shoot there,” says Cameron. “But the library, kitchen and study were built on the stage. They were interesting sets to build and dress since they include a significant amount of props.”

“Obviously, we based the architecture of the set pieces on the architecture in the real château,” Cameron continues, “the beautiful carvings, mouldings and cornices. We took all the dressing out of the real château and put in our own so that it looked more like Teabing’s residence. As we move into the study and library, which is his den, it reflects his character and we designed many of the props with Teabing in mind.”

Background – The Works of Leonardo Da Vnici: Art & The Da Vinci Code

The Last Supper

In The Da Vinci Code, the character of Sir Leigh Teabing (Ian McKellen) offers a unique interpretation of this legendary painting, which Leonardo da Vinci started in 1495 and completed in 1498. Commissioned by his patron, the Duke of Milan, Ludovico Sforza, The Last Supper is in fact a mural painted directly onto the refectory wall of the Santa Maria delle Grazie monastery in Milan.

The painting, which measures 15 feet by 29 feet, portrays the moment after Jesus informs his apostles that one of them is about to betray him. The natural way the apostles’ emotions are depicted, ranging from shock to consternation to the covert lack of expression on the face of Judas, was radically different from anything that had preceded it. The painting is anachronistic, using the kind of table, tablecloth, upright chairs and cutlery that would have been in everyday use by the monks in the 15th century.

Leonardo arranged the apostles in four groups of three, with Christ in the center, set apart from the apostles with empty space around him. The one-point perspective creates a central triangle composed of two triangles on each side. To the right of Jesus is the feminized figure of a young apostle, a central clue to the shocking conclusion of The Da Vinci Code.

Unfortunately, Leonardo chose not to use the conventional method for painting frescoes, which was to apply egg tempura on wet plaster. Instead, he painted directly onto the dry wall. By 1556, the art historian Vasari wrote that the painting had deteriorated so badly that only the vague shapes of the figures remained.

Mona Lisa

The Mona Lisa is one of the most famous and recognizable portraits ever painted. Leonardo began painting this enigmatic woman with a curiously inviting smile in 1503 and may have continued working on it for years. Three years before his death, when Leonardo went to France to work for the young King François I, he took the portrait with him. The painting was first displayed at Fontainebleau, then at Versailles, and finally in the Louvre, where its unknown subject now smiles through protective glass as rapt throngs wait to see her. The Mona Lisa is arguably the museum’s most popular attraction.

For many years the painting was known as La Gioconda, since the portrait’s subject was believed to be Elisabetta, third wife of the Florentine merchant Francesco del Giocondo. But the painting remains the subject of speculation. Some even believe Leonardo used himself as a model, others that the woman was a mistress of one of the Medicis.

Actor Jean Reno has been enamoured with the painting for most of his life. “I come back again and again to the Mona Lisa,” he says. “For me, it has what I call a kind of perfume, because when you turn around, the eyes seem to be following you. It’s this exchange between the painting and the observer that I refer to as its perfume, its ability to intoxicate. While others say the power of Da Vinci’s work is in her smile, for me it is her eyes.”

Adds Howard: “There’s just something mesmerizing, engrossing and thought provoking about the Mona Lisa. This is why the painting is a great choice as an iconic reflection of the movie and as a graphic, identifiable image related to the story of The Da Vinci Code – not only was it painted by Da Vinci, but its enigmatic, mysterious quality perfectly mirrors the movie’s themes.”

Virgin of the Rocks

In 1483, Leonardo was commissioned to paint a work intended to be the center of an altarpiece. There are two paintings of the Virgin of the Rocks-the original on canvas, which hangs in the Louvre, and a later copy painted on wood, which is in the collection of the National Gallery in London-depicting the Virgin Mary sitting with the infants Jesus and John the Baptist, accompanied by the Archangel Uriel.

The painting, sometimes called the Madonna of the Rocks, figures in the complex mystery of The Da Vinci Code.

History & The Da Vinci Code

The Knights Templar

The Knights Templar came into being in 1118 after the holy city of Jerusalem (which had been conquered in 614 A.D. by the Caliph Umar) was recaptured by Christian forces during the First Crusade. The new Kingdom of Jerusalem was ruled by Baldwin I, crowned in 1100, and the Knights, led by Hugues de Payens, occupied a wing of his castle in the former Al Aqsa Mosque, where the great Temple of Solomon had once stood.

As a result, they soon became known as the Knights of the Temple, or Templars. The Knights were a monastic military order dedicated to the protection of Christian pilgrims visiting the Holy Lands. As knightly monks, they took vows of poverty and celibacy. Their emblem was a red cross on a white tunic, while their sergeants (who were not members of the nobility) wore red on black. The order was endorsed by Bernard, the powerful Abbott of Clairvaux (founder of the Cistercian Order, later beatified as St. Bernard) and the order was officially recognized by the Church at the Council of Troyes in 1128. It is probable that Bernard wrote the Templars’ “Rule,” which swore allegiance only to the Pope.

These fabled warriors soon began expanding their mandate from protecting pilgrims to fighting for all the causes of the Holy Kingdom of Jerusalem. They went from protecting property for absent pilgrims to banking – loaning would-be pilgrims funds for the journey against their property – and levying taxes as well as collecting tithes. Their land holdings and wealth soon became vast, and their influence was sufficient to provoke resentment by political leaders, who were never able to gain control of them.

The Templars’ holdings stretched across Europe and included castles in the Holy Land and Cyprus, and their knowledge of the East inevitably involved them in politics. They were the forerunners of the modern professional military, a dedicated, well-trained and disciplined institution that eschewed individual heroics in favor of the greater goal.

The Templars’ chief rivals were the Hospitalers, an order begun in 1070 to care for pilgrims and provide the less wealthy with lodging. They, too, quickly evolved into a military order with great power and wealth. The refusal of these two powerful orders to work together and increasing indebtedness to them became a major headache for Europe’s secular rulers, but the Hospitalers continued with their charitable works, which deflected the wrath that eventually destroyed the Templars.

On Friday October 13, 1307 (believed to be the origin of the superstition that Friday the 13th is an unlucky day), King Philip IV of France issued orders for the arrest of the Templars and confiscation of their property. The captured Templars were tortured and confessed to a variety of heresies and perversions. In spite of efforts to save the order – in a few trials members were found innocent – the forces against them were too determined, and Jacques de Molay, the order’s last Grand Master, was burned at the stake in 1314, ending the Knights Templar after 200 years.

The Priory of Sion

In his novel, The Da Vinci Code, author Dan Brown contends that the Priory of Sion is a real organization founded in 1099, and that parchments housed at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris reveal that its membership included many leading figures of literature, art and science. However, the documents in the Bibliothèque Nationale have been revealed to be modern forgeries placed there by Pierre Plantard, who admitted to having “founded” the Priory with three friends in 1956, either as a lark or part of a con. He was elected the Grand Master of the Priory in 1981.

The phoney documents and manuscripts, which have become known as the “Dossiers Secrets,” claim that the secret organization was founded in 1099 by Godefroy de Bouillon, who led the first army to depart for Jerusalem during the First Crusade, and was the original ruler of the recaptured Holy Land. The Priory is also given credit for the creation of the Knights Templar, which supposedly then split with them some 100 years later.

The Da Vinci Code Locations

The production team on The Da Vinci Code travelled from Paris to the United Kingdom to Malta, stopping at some of the most fascinating and significant historical landmarks in Europe.

Although a number of sets were built at Shepperton and Pinewood Studios, the majority of the film’s key scenes were shot on location. Says Tom Hanks: “We were in many of the actual places mentioned in the book, with all the amazing historical significance that entailed. We got to crawl through some little doors and kneel on some very hard floors. Without a doubt, however, it helped me as an actor to go even farther into my portrayal of Robert Langdon. It was a very different experience than driving to a Hollywood studio every day and going to Stage 6 to shoot your scenes.”

France

The initial scenes of The Da Vinci Code were shot in the streets of Paris, where the intricate and exciting Smart-car chase scenes took place at the legendary Musée du Louvre and outside the city at the Château de Villette near Versailles.

Originally constructed as a fortress to protect the Right Bank in the late 12th century, the Louvre has played a long and varied role in Parisian history. It first was transformed into a Gothic royal residence in the 14th century by Charles V, and then ambitiously recreated as a Renaissance palace in the 16th century for King Francois I, the last patron of Leonardo da Vinci.

The Grande Galerie opened as a museum in 1793. Nearly 200 years later, after many more changes and extensions, Chinese-American architect I.M. Pei designed new underground spaces as well as the controversial glass pyramid that now serves as the museum’s entrance and is an important symbol in the movie.

The production was fortunate enough to be one of very few granted access to film inside the museum’s Grande Galerie after hours. “We felt extremely privileged to be able to shoot there. It’s a magnificent touch for the film,” says Hanks.

Adds his co-star Audrey Tautou: “I really liked that we were able to be in the Louvre at night and have all the paintings and the statues to ourselves. It was a truly stimulating and intoxicating experience.”

Director Howard likened his adventure inside the Louvre to spelunking. “It’s a little bit like going into a cave and shining your light around and seeing the amazing formations. When you’re in the Louvre alone, you feel like you’re in a cavern with manmade treasures, art treasures. As a filmmaker it is humbling to stand in awe at the sheer volume of great work that resides within the walls of this one museum.”

The character Sir Leigh Teabing (Ian McKellen) lives in the Château de Villette, which lies northwest of Paris, close to Versailles. (Langdon and Sophie arrive there late at night in the armored truck they have appropriated to seek his advice on the Holy Grail.) Completed on or about 1696 for François Mansart, the Count of Aufflay, (Ambassador to Venice under King Louis XIV), the impressive 185- acre estate includes two rectangular lakes, cascading fountains and beautiful gardens designed by André Le Nôtre, who also designed the gardens of the Palais de Versailles. Filming took place over three nights on the grounds of the Château, though the majority of the interiors (apart from the foyer) were filmed on various soundstages at Shepperton Studios.

United Kingdom

Travelling to London to find additional clues in solving the riddle of the cryptex, Langdon, Neveu and Teabing race to Temple Church, which is located between Fleet Street and the River Thames. The church, consecrated in 1185, was one element of a temple constructed in the 12th century to serve as the headquarters in England of the Knights Templar. The church is divided into two parts, the original Round, and the rectangular Chancel, completed in 1240. The Round was designed after the round Holy Church of the Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Nine lifesize stone effigies of knights lie on the floor.

After the destruction and abolition of the Knights Templar in 1307, the rival Knights Hospitalers took over until they were ousted and their properties seized by Henry VIII. The Crown eventually rented parts of the temple to two colleges of lawyers, collectively called the Inns of Court, who use it and the surrounding area to this day. The church was bombed in 1941 during WWII, and has been painstakingly reconstructed, down to its leaning marble columns.

Soon after exploring Temple Church, Langdon realizes that they have come to the wrong place and after some research, he and Sophie set off for Westminster Abbey. Although the exterior street scenes outside the Abbey were shot adjacent to the actual location, the interior scenes of the Abbey and the Chapter House were shot at Lincoln Cathedral, three hours north of London.

Lincoln Cathedral, consecrated in 1092, was built by Bishop Remigius on orders of William the Conqueror, and is a universally admired example of Early English Gothic architecture. It has survived earthquakes, fires and collapsing spires over the centuries. The central tower rises to 271 feet and remains the highest cathedral tower in Europe without a spire, and during the 200 years that the original spire stood (before collapsing in 1594), it was the world’s tallest structure.

Lincoln Cathedral has played a prominent role in English history. A bishop of Lincoln was one of the signatories of the Magna Carta, an original copy of which is still housed in the castle adjacent to the Cathedral.

The logistical difficulties of such a high profile film unit shooting on a street outside Westminster Abbey, one of London’s biggest tourist attractions, were enormous. However, as with much of the shoot, passers by were more excited than irritated by the shut down roads, and in the case of Westminster Abbey, they ended up as extras in the film.

Explains Howard: “The nature of the scene we were shooting was the climax of the story, and I will never forget the hordes of onlookers that we were not allowed to control or partition off, or even get out of our frame. So we had to devise a way so that we could just shoot with them there, and at the time I was thinking, `This is going to be a disaster.’ But we asked for the crowd’s co-operation and they obliged. It was raining a bit, but not enough so that it could be seen on film. We’d started the scene dry, so we asked that, even though they were getting rained on for a certain take, would they take down their umbrellas, and they obliged. We also asked for no flash photography, no yelling over the actors doing their dialogue. They worked with us, applauding the actors after each take. British good manners really came into play that day.”

Langdon and Neveu’s quest finally ends at Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland. Rosslyn Chapel is located seven miles south of Edinburgh, in the town of Roslin, which was created to house the chapel’s masons. The Chapel was founded in 1446 by Sir William St. Clair, Prince of Orkney, who presumably intended to build a far larger church to be laid out in the shape of a cross. Work was halted when Sir William died in 1484.

The Gothic Chapel, which measures only 69 feet by 35 feet, contains intricate stone carvings that capture the imagination, ranging from traditional Christian depictions to Norse and Celtic myths to the supposed death mask of Robert the Bruce. There are dragons, devils and 100 Green Men. It’s no wonder the chapel has so captured writers – Sir Walter Scott and William Wordsworth among them.

Legend surrounds the chapel, and it’s said that William St. Clair was a Grand Master of the Templars. Another legend, suggested by stone carvings that appear to be rows of corn – a New World vegetable as yet undiscovered at the time of the carving – is that a grandfather of William St. Clair may have reached Newfoundland in 1398 and travelled south into Massachusetts.

The Lincolnshire countryside stood in for Italy with Burghley House in Lincolnshire substituting for Castle Gandolfo, where Bishop Aringarosa journeys to take delivery of a fortune in Vatican bearer bonds. Burghley House was built and designed (in the main) by William Cecil, Lord High Treasurer to Queen Elizabeth I, between the years 1555 to 1587, and is widely regarded as one of the finest examples of Elizabethan architecture. There are more than 100 rooms in the house, and the production used, among others, the magnificent Heaven Room and Hell Staircase, both painted by Antonio Verrio.

Malta

The last stop for the production team was the island of Malta, where a number of flashback sequences were shot, including scenes set in the Holy Land and Spain. Situated at the heart of the Mediterranean, Malta has been a crossroads for ancient and modern seafarers, which is reflected in the island’s varied architecture. In particular, one of the film’s locations, the fort at Vittoriosa, was the Knights of St. John’s (the Hospitalers) home after they had been driven from Rhodes. For a period of 250 years, the Knights ruled from Malta to defend Christianity from the Ottoman Empire. They were finally disbanded by Napoleon.

The Da Vinci Code (2006)

Directed by: Ron Howard

Starring: Tom Hanks, Jean Reno, Audrey Tautou, Ian McKellen, Alfred Molina, Paul Bettany, Jürgen Prochnow, Jean-Yves Berteloot, Etienne Chicot, Marie-Françoise Audollent, Rita Davies

Screenplay by: Akiva Goldsman

Production Design by: Allan Cameron

Cinematography by: Salvatore Totino

Film Editing by: Daniel P. Hanley, Mike Hill

Costume Design by: Daniel Orlandi

Set Decoration by: Richard Roberts

Art Direction by: Giles Masters, Tony Reading

Music by: Hans Zimmer

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for disturbing images, violence, some nudity, thematic material, drug references, sexual content.

Distributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: May 19, 2006

Visits: 55