Tagline: Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

In 1971, Clifford Irving achieved the very heights of American journalism, nabbing a series of unprecedented interviews with the most famous man in the world – ultra-reclusive, immensely powerful, superstar billionaire Howard Hughes – revealing his most intimate memories and controversial secrets. Actually, that’s a lie.

Now from Academy Award-nominated director Lasse Hallström (Cider House Rules, Chocolat) comes THE HOAX, a riveting caper inspired by Irving’s untrue story. Jumping off from the still controversial facts surrounding Irving’s ruse into a fictional reverie, the film mischievously and imaginatively explores how a man, an industry and an entire nation could become intoxicated by a good story… in sheer defiance of the fact that it never really happened.

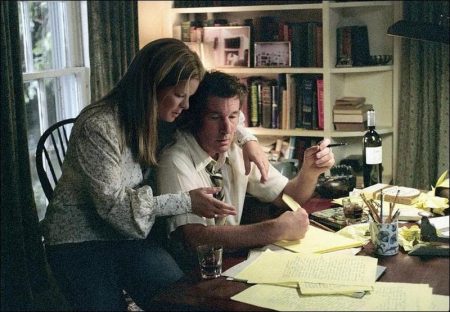

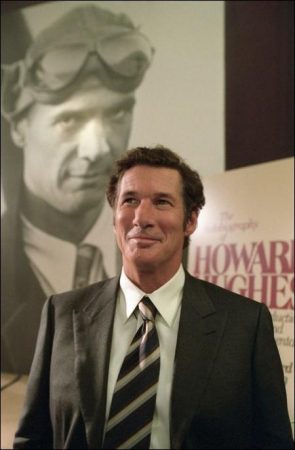

Golden Globe winner Richard Gere takes on the roguish role of Clifford Irving, an ambitious yet struggling writer who’s been looking for that one big story for so long, he brazenly decides to make one up. At first the idea is just a savvy artistic prank, but if that’s what the world wants, Irving believes he can take it further.

Shrouding himself in a clever cloud of secrecy, he drops the news to a major publisher that he has been approached by the one man the entire world most wants to know about – aviator, movie mogul, ladies man and eccentric billionaire Howard Hughes – to ink his priceless biography.

There’s just one little problem: not a word of what Clifford is saying has an ounce of truth to it. He’s never so much as seen a glimpse of the real Howard Hughes. But Irving banks on the idea that Hughes’ seclusion and notoriously thin hold on reality will allow the con to succeed. Hughes has not been seen or heard from in public for over a decade. He is a total recluse. Irving relies on this fact to protect his bogus story – as Hughes refuses to confirm or deny anything so prevalent is his fear of appearing in public. Recruiting his anxiety-prone but loyal best friend Dick Suskind (Alfred Molina) and European artist wife (Academy Award winner Marcia Gay Harden) into the scheme, Clifford soon finds himself in a wild maze of treachery, as he is forced to dodge the fallout of his falsehoods at every turn. What started as an adventurous lark soon turns into a seemingly inescapable maze of forgeries, thefts, tall tales, deceptions and impersonations.

Yet Clifford’s plan works like magic as his publishers, hungry for a bestseller at any cost, are hoodwinked by the thrill of it all. When Clifford stumbles upon possible links between Hughes and a corrupt Nixon administration, the stakes for his book grow even higher. Clifford is on top of the world… until the real Howard Hughes shockingly emerges to pull the rug out from under him. Only now, Clifford is so caught up in the tale he created that he may no longer know where his incredible story ends and reality begins.

The Hoax is a 2006 American drama film starring Richard Gere, directed by Swedish filmmaker Lasse Hallström. The screenplay by William Wheeler is based on the book of the same title by Clifford Irving. It recounts Irving’s elaborate hoax of publishing an autobiography of Howard Hughes that he purportedly helped write, without ever having talked with Hughes. The film was ranked as one of the Top 10 of the year by the Los Angeles Times and Newsweek.

The screenplay was considerably different from the book. Hired as a technical adviser to the film, Irving was displeased with the product and later asked to have his name removed from the credits. The Hoax was given a limited opening in 235 theaters in the United States and Canada on April 6, 2007 and earning $1,449,320 on its opening weekend. It eventually grossed $7,164,995 in the US and Canada and $4,607,188 in foreign markets for a total worldwide box office of $11,772,183.

Inside the Hoax: About the Film’s Origins

From fabricated books to faked news stories, the media hoax has become a staple of modern American culture — one of the fastest and most irresistible routes to fame, fortune and adoration in a world that loves a good story, sometimes at any cost. But our current era of constantly erupting scandals was kicked off by perhaps the most spectacular swindle of them all: the Clifford Irving/Howard Hughes hoax of the early 1970s.

The true story of Clifford Irving was so outrageous that when THE HOAX’s screenwriter William Wheeler first heard it, he thought it was made up – and things only got more complicated from there, as he and director Lasse Hallström decided to fictionalize this truth-inspired tale built on a series of deceptions and lies.

“When producer Josh Maurer and Mark Gordon first told me the concept for THE HOAX, I thought it was too absurd to be believed. Then they told me it was based on something true which made it even more incredible!” recalls Wheeler.

The basic facts of the story were these:

In1971, McGraw-Hill announced it had acquired for the then-immense sum of nearly a million dollars the rights to publish Howard Hughes’ memoir. This would have been the publishing coup of the century. At the time, Hughes was the richest, most powerful man in the world, yet this prevailing icon was so reclusive that just about everybody wanted to know more about his mysterious, secretive and alluring personal life.

The fact that the purported author wasn’t one of the country’s leading journalists but a little-known writer named Clifford Irving did raise some eyebrows. Irving, in fact, had previously written a book entitled FAKE!, all about the inner workings of art forger Elmyr de Hory, which could have tipped someone off. But no. Instead, McGraw-Hill claimed that it was satisfied that Irving had obtained not only Hughes’ blessing but extensive intimate interviews with the man who would allow no one else near him. After all, Irving had produced documents from Hughes that even passed the snuff of the publisher’s so-called handwriting experts. But just as the Howard Hughes biography was about to hit the stands, Hughes made his first public statement in over a decade – holding an eerie, disembodied telephone press conference from the Bahamas to declare Clifford Irving and his book a giant fraud.

It turned out the Irving had fabricated the entire volume – in part from his own imagination and in part from a stolen, unpublished manuscript written by Noah Deitrich, Hughes’ former right-hand man, as well as peppered with historically accurate facts obtained through legitimate research by Irving and Suskind. Indeed, Irving had never so much as spoken a word to Howard Hughes. Ultimately, Irving would be named Con Man of the Year by Time Magazine and would spend more than 2 years in jail, as would his researcher and collaborator Dick Suskind and his Swiss wife, who became his financial accomplice. When he got out, Irving wrote a different memoir – his own this time, and one purportedly more factual, recounting the behind-the-scenes details of creating the bogus autobiography — and called it The Hoax.

Irving’s book wound up in the hands of producer Josh Maurer, who found himself drawn not only to the story of one of the first earth-shaking media scandals of our recent times, but to the idea of Irving as an wonderfully funny, unpredictable and irreverent movie character. He could, Maurer, realized be the ultimate “unreliable protagonist,” a man so brilliant at lying, he started to buy his own falsehoods. He also provided an intriguing path into a period in American history when both personal trust and the national trust were being shattered by changing lifestyles and political corruption.

“I loved all the elements of the story – the connection to Howard Hughes, the way this scandal impacted the world press – but most of all it was the characters that really got me,” says Maurer. “Clifford Irving got under my skin. He was a very charismatic man who found himself in a kind of mid-life crisis. He saw his youth passing away and he found a way to use his imagination to try to stop that – only he didn’t see the ramifications of what he was doing, for himself, his wife or his best friend. Since his success as a writer did not bring him the critical recognition he desired, he created the extraordinary tale of the Howard Hughes autobiography but made himself the center of the story – and in the end he became his own greatest creation as the author of this hoax.”

Maurer saw right away that Irving’s hoax would be rich material for the right screenwriter to mine. “On the one hand, the story is hysterically funny, it’s great black comedy, but it also has elements of a very suspenseful thriller. It’s very much about the nature of obsession – obsession for storytelling, obsession for passion, obsession for money and obsession for fame and recognition,” he says. “Then there is the whole interesting dynamic between reality and illusion, another major layer in the tale.”

Maurer brought the project to producer Mark Gordon, who was equally intrigued by the bevy of comical characters and complex themes the story presented. “There have always been con men and hoaxsters in America and there’s something about human beings that I think will always be fascinated by those who dare to pull the wool over other people’s eye,” Gordon says.

He continues: “Clifford Irving was just so incredibly audacious. Each thing he did was more outrageous than the next. The fact that he was willing to go to the lengths he did to pull this off, going deeper and deeper into deception and duplicity, plays like fiction, but it’s true.”

Producers Maurer, Gordon and Betsy Beers then approached rising screenwriter William Wheeler, who – after getting over his shock that the story of Clifford Irving was based in reality – couldn’t wait to explore the story deeper. Having been a telemarketer himself (his first film, The Prime Gig, starred Vince Vaughn as a shady telephone salesman), understood the slippery nature of the sophisticated con. Wheeler and Maurer began with intensive research into the story’s many layers, from delving into Howard Hughes’ strange exiled existence to probing the ties between Howard Hughes, Clifford Irving and another historical person famed for unfortunate lies: Richard Nixon. Next the team brought the project to Bob Yari. Together, they decided to make the picture independently through Gordon’s partnership at the Stratus Film Company.

Best of all, the writer had the chance to meet the real Clifford Irving, whose slippery psychology was Wheeler’s main interest. “He was very hospitable, very warm and completely unreadable,” Wheeler confesses. “He’s a true operator, and I say that being a bit of an operator myself.”

Wheeler posed the essential question to Irving, but didn’t necessarily buy his response. “I asked him, why did you do it?’” Wheeler recalls. “And Clifford said, `it was my Everest. I did it because it was there.’ But I think that’s a little too easy. I think he was a middle-aged man who wanted a sense of accomplishment, of meaning something and I think this hoax was his way of expressing that,” he says.

Yet Wheeler was also completely won over by Irving and his unsinkable irreverent spirit. “The thing that most fascinated me about Clifford as a film character is that every time he gets in trouble he doubles down – he further increases the stakes, which keeps even the most skeptical people distracted. I was really drawn to that,” he says. “It was a chance to really dig through all the layers of these cons and lies and try to figure out what happened and why people did what they did.”

Wheeler himself didn’t want to be beholden only to the facts and spun a few yarns of his own in writing the screenplay He comments: “I don’t think you could do this story justice without bringing a bit a mischief to it. We each added our own creative touches to the tale – starting with Howard Hughes to Clifford Irving to me to Lasse Hallström to Richard Gere.”

But the one thing that always stayed real for Wheeler was his sense of Clifford Irving as a human being, especially when it came to his friendship with his faithful, if faint-hearted, writing partner and fellow fraudster Dick Suskind. Their relationship becomes one of increasingly tight reliance on each other as their web of lies grows thicker and thicker – and the engine which drives Wheeler’s story.

“I thought audiences would really be able to relate to the idea of these two friends whose incredible lie bound them together,” he says. “Their friendship is the foundation of the story.”

The film’s producers were completely behind Wheeler’s adventurous, multi-layered approach to the story – after all, how else could you get to the heart of why a man would risk everything on one outrageous lie and why everyone around him would hungrily buy it? “The story as William Wheeler re-created it makes for a wild ride,” Josh Maurer summarizes of their reaction. “It’s an incredible experience that these two friends go through, and I think it’s an experience that audiences haven’t really had before.”

Probing the Hoax: Lasse Hallström Comes on Board

For Academy Award nominated director Lasse Hallström, THE HOAX marks an edgy departure back to his roots, a foray back into the darkly comic labyrinths of irreverence, obsession and deception. Having gained renown for his deft storytelling skills and sensitivity in working with actors, Hallström’s recent body of work – including the award-winning Cider House Rules and Chocolat – has veered towards moving dramas. But Hallström began his career in his native Sweden with a series of keenly observed comedies, ultimately coming to global attention with the runaway hit about the grittier, wryer side of childhood, My Life as a Dog.

Hallström says that, no matter what the subject, his passion for filmmaking has always been driven by one thing: character, regardless of whether those characters are inspirational or downright morally befuddled. And it was character in spades that lured him to THE HOAX as soon as he encountered it. “I just loved the script right away because these characters are so fascinating,” he says. “It was a chance for me to do the kind of film I’ve been wanting to return to for a long time, the kind of comedy I like most – the kind that fearlessly observes human behavior, in the tradition of Milos Forman and John Cassavetes.”

Recalls Hallström’s long-time producer Leslie Holleran: “There was a rare, instantaneous connection to this material. We felt there is a core here, there is a human story that we like, and we wanted to tell it. Lasse and I are also always trying to reach out and try something new and different and there were many new elements to this story that were very, very exciting to us.”

The other producers were exhilarated by Hallström’s fervor for the project. Says Josh Maurer: “We already knew that Lasse is a brilliant storyteller who has a way of bringing extraordinary performances from actors – but this is a story Lasse has never told before, and that was very exciting to us. It was a great and unexpected match.”

Hallström had never heard of Clifford Irving before he read the script, and as with William Wheeler, he was knocked for a loop to realize someone had really succeeded in hoodwinking so many people with such a bold and outrageous series of lies. He brought his own take on Irving to the picture – viewing him as a playful, imaginative con artist, emphasis on the artist, who conjured his own amazing fantasy world from thin air and then attempted to live in it as a reality.

“I saw Clifford Irving as more like a performance artist, who saw this scam, this hoax, as an incredible act of creation,” says Hallström. “It wasn’t so much that he needed the money. It was the fun of it all, the art of it all that really got him going. He made a world out of nothing. But then I think it got out of control. He kept raising the stakes and getting more and more caught up in the fraud. It started out at a very playful level but it escalated into an increasingly serious illegal scam.”

Hallström was willing to take the risk of allowing the story’s main character to be drawn entirely in shades of gray, sometimes oozing charm and wit, and other times devastatingly amoral. “I was always torn over what to think about Clifford, because he’s really not trustworthy, and the way he uses and betrays his friends made me cringe,” Hallström admits. “But it also constantly fascinated me, because I could never lie to that extent, and yet I think we all wonder about people who are able to make lying and cheating their way to the top work. What’s so wonderful about Clifford, especially as Richard Gere portrays him, is that he’s not a complete villain. You can understand him, even if you can’t trust him.”

For Mark Gordon, it was Hallström’s ability to braid together all the strands of this grand hoax that made him so right for the material.“He uses a style in which humor and drama and intrigue all work together seamlessly. That’s a hard thing to pull off, and I think Lasse has done it remarkably well,” says the producer.

Once on the set, Hallström fostered a fast-and-loose improv style amidst his talented cast that pushed their barriers and suited the jazzy, unpredictable nature of the story. “It was a very relaxed approach to the script, where we would go off it at times and just play,” he explains. This was especially true in the scenes between Richard Gere and Alfred Molina, during which Hallström wanted the actors to effuse the spontaneity and creativity of the two men’s unusual friendship. “They’re both wonderful improvisers and very funny,” says the director. “There was a real spark between them.”

Cultivating sparks was the crux of the entire production for Hallström. “The whole production was designed to focus on performances,” he sums up. “And it was truly fun to watch so many creative people telling this story together.”

Playing Out the Hoax

Clifford Irving is a charming husband, an affectionate friend and a very smart and talented writer. Clifford Irving is also a philanderer, a betrayer and outright lying fraud. He’s a character full of charisma and playful mischief but winds up trapped in a increasingly dark, thick web of his own making. So who could play such a character?

It wasn’t long before the filmmakers turned to the idea of Richard Gere, who recently won acclaim for his razzle-dazzle performance as smooth-talking, tap-dancing, Jazz Age attorney Billy Flynn in Chicago, a performance which earned him widespread accolades and a Golden Globe. “I’ve always wanted to work with Richard and he was a perfect fit for this character,” says Lasse Hallström. Continues Leslie Holleran: “Clifford Irving is the consummate seducer. He’s the kind of person who walks into the room and charms everyone. So, in a sense he’s an actor, and I think Richard really understood this completely. He knew who this character was and it was as though he was channeling him.”

Gere found himself wrapped up in the story from the get-go. “It was one of those rare scripts where you go, `wow that’s really interesting and fresh.’ I was intrigued by the idea that this story was about being a fake on all kinds of levels – a personal level, a psychological level, a political level. Also, I thought the script really captured the schizophrenia of that time in America, and the coming together of all these elements of that period – the New York publishing industry and Watergate and Nixon and Vietnam and Pop Art – in a wonderful way that just called out to be made,” he says.

Once Gere committed to playing Clifford Irving, he jumped in at a sprint, even changing his physical appearance for the role. “Richard completely and utterly threw himself into the role and made it is his own,” says producer Josh Maurer. “It was an extraordinary thing to watch an actor of Richard’s stature take on and completely become this very different character.”

Mark Gordon adds: “Richard brought an enormous amount to the table and I think will surprise people because they’ve never seen him do a role like this before. Clifford is an incredibly charming guy, but not in the way we think of Richard being charming. He’s funny and outrageous.”

In approaching the role, Gere made the decision not to meet with the real Clifford Irving – especially because the film isn’t a biopic but a playfully fictional account of Clifford’s hoax. To put it succinctly, Gere worries that Clifford Irving, hoaxster that he has been know to be, could get in the way of finding the truth of the role. “I didn’t want to meet him,” he admits. “I was kind of afraid, actually. I had a strong idea of how I wanted to do this and I didn’t want to be overly influenced by his point of view on what happened. I didn’t want any constraints at all. I wanted to let my imagination go while I was doing it, and that’s what I hooking into.”

Gere found that he could relate in some ways to Irving’s predicament at the outset of the story, as a man in search of great material. “As a writer, he’s always waiting for that next deal, so he has the same insecurity that an actor does where you do a project but you never know if there’s ever going to be another one,” he explains.

But what fascinated Gere most was how carried away Irving became once he decided to pretend to know Howard Hughes. “The idea started out maybe as a comment on fame, as a kind of Pop Art, as a pointed game, but the more people buy into it the more real it becomes to Clifford. Psychologically, he crosses the line,” says Gere. “Howard Hughes was the perfect subject, too, because he was so deeply mysterious. People made up all kinds of stories about him as this mad mystic or conspirator – some crazy, some perhaps true. There was a romance around all of this that Clifford Irving really keyed into.”

Gere also believes that Irving came within an inch of pulling the whole incredible scam off. “If Howard Hughes himself hadn’t spoke up, it probably would have happened. Everyone wanted it to happen. Everyone wanted it to be true because it was such great a story and they could see dollar signs,” he observes. “If you see some of the forgeries Clifford gave to McGraw-Hill, they’re just really amateur jobs, but people wanted to believe and Clifford must have felt as if he and Dick Suskind and his wife were under some kind of magical spell where they could not be disbelieved.”

Ultimately that spell would be broken, however, and although there were a lot of fun and high energy scenes for Gere, they would becoming increasingly dark and intense. “There was a lot of fairly deep, creative work on this film. There were also lot of improvised scenes where Alfred Molina and I would fly into some very spontaneous territory,” he notes. “The great thing is that Lasse creates an environment which is especially good for actors. He gives you the space to try new things and go fearlessly in different directions. But at the same time, you know he’s absolutely in control.”

The story of Clifford Irving hinged not only on casting the lead role but equally on casting on the people who became Irving’s partners in crime – his best friend Dick Suskind and his wife, Edith. The role of Dick Suskind was particularly complex, as he becomes not only Clifford’s loyal buddy but increasingly his only link to moral conscience, not to mention his panic attack-prone worry. To get inside Dick’s layers, Lasse Hallström turned to a consistently award-winning star of stage and screen with whom he had worked on Chocalat: Alfred Molina.

“We love and adore Alfred, who is so funny and talented,” notes Leslie Holleran. “He winds up with these great, funny moments as Dick, because he is so perfect as the unwilling, begrudging participant.”

Molina was excited to work with Hallström again, especially on such an utterly opposite project. “It’s always nice to go back to work again with a director with whom you’ve had a good experience,” he says. “You can work more intimately and constructively, I think. And Lasse always gives you the freedom to be as inventive as you can.”

With the character of Dick Suskind, Molina knew that freedom to be inventive would be vital. “It was really important to capture that kind of friendship that Clifford and Dick had – they were very close friends who shared a lot of secrets together,” notes Molina. “And the question for Dick is how far are you willing to go when your friend is in trouble and needs you.? What turns out as a prank turns into something meaningful between them as friends.”

As in many male friendships, Molina sensed a bit of envy mixed with admiration in Dick’s view of Clifford – and is this that leads Dick down a criminal path he would never have ventured into on his own, leaving him on the verge of a heart attack at times. “I think Dick sees Cliff as the kind of man he would, perhaps, like to be,” says Molina. “He sees elements of Cliff that are very attractive, especially his intellectual bravery, his recklessness and his artistry. Comparatively, Dick feels very mundane – he’s a researcher who writes educational books and doesn’t have the same creative freedom that Cliff enjoys. He’s bound by the conventions most of us are: marriage, kids, his job. And so he sees this adventure as a way to get a taste of Cliff’s more exciting world.”

Fortunately, Molina and Gere proved to have a remarkably natural, humor-filled rapport with one another and an equal commitment to creating an authentic male friendship on screen. “Alfred and Richard both really invested their performances with the affection and caring that comes with real friendship. It was thrilling to watch that,” says Josh Maurer. Adds Marks Gordon: “In the film, the relationship between Cliff and Dick is very comical. Dick is the poor bastard who goes along with Cliff and gets pulled deeper and deeper into this mess of lies. One is sort of the king, the other his minion, but they are always very funny and interesting together.”

Says Molina of his collaboration with Gere: “We had a wonderful time working together. We discovered a mutual enjoyment in playing around with the script and trying to always keep things fresh. There was a certain amount of tomfoolery naturally involved with us – and that was good for the movie.”

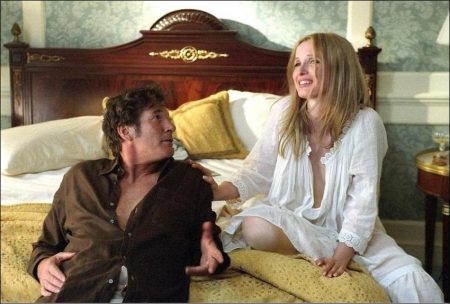

Another essential relationship for Clifford Irving is that with his idealistic artist wife who, despite her awareness of Clifford’s constant infidelities, risks her own future to help his scheme. Irving’s real wife, Edith, was a Swedish citizen of German background so Lasse Hallström knew he needed an actress who could not only embody Edith’s complicated dilemma but also her Swedish-German accent. He found what he was looking for in one of today’s most sought-after screen actresses: Marcia Gay Harden, who won an Oscar playing Lee Krassner, Jackson Pollack’s artist wife in Pollack, and garnered an Academy Award nomination for her work in Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River.

Harden found the script provocative and the role unlike any she has done before. “What people will risk is shocking, what people will sacrifice for a moment of glory is fascinating to me,” she says. “And the character of Edith is so colorful, I thought it would be kind of a far step away for me to try to enter her. That’s always an exciting for an actor to do.”

The actress was quite moved by Edith’s plight. “I think she is such a sad character because she wants so much for her husband just to love her, to admire her painting, to commit to her, and he is unable to do that. In every way he is a cheater and yet, in every way she loves him so much,” she observes. “And both she and Dick do things they would never normally do for this man. Edith thinks that if she helps him, he’ll think she’s ballsy and brave and tough and love her for that. But in the end, she did more jail time than he did.” Yet she also found the story increasingly funny. “I thought the script had humor in it but there was even more on the set,” she says. “Lasse’s vision of thing always finds unexpected humor.”

When it came to Edith’s accent, Harden had a little bit of a head start. “I’d lived in Germany before so I knew a bit of the accent,” she says, “but Edith is Swiss-German and had also lived in Spain and London, so she had a mishmash of sounds in her accent. I had a videotape of her so I knew her accent was really quite strong and very pronounced and rather big. I worked with a great dialogue coach in New York, Sam Scwhatt, and we found a way to use traces of that.”

Harden was especially excited to join with Gere and Molina in creating this unlikely criminal trio. “Alfred Molina as Dick just breaks your heart,” she says. “You laugh at him and yet you love him. And Richard is the mastermind. Both of these boys are full of laughter and love of their craft and respect for the creative energy it takes to enter characters like these. It was serious work, but we had a lot of fun.”

Designing the Hoax: About the Film’s Style

THE HOAX takes place at once amidst the cosmopolitan, freewheeling atmosphere of the stylish 1970s media world – and in a less anchored realm of flashbacks, hallucinations, paranoia and deceptions. Since Lasse Hallström wanted the characters to always be front-and-center in the film, he envisioned a look for the film that, at times, would feel almost documentary-like in its realism, yet that would also occasionally slip into moments that defy realism. Also key to his approach to the film was capturing the zeitgeist of the 1970s, when politics and talk of lies and corruption were everywhere in the mass media – and yet on the periphery of Clifford Irving’s life.

“It was important to capture a historical sense of those times, even though the story is so relevant to today,” says Josh Maurer. “We wanted to have in the background a sense of everything that was happening in America with Vietnam and Watergate and the whole Anti-Establishment mentality that obviously affected Clifford and Dick as they were writing. Filled with all these elements, the photography, the production design and the costumes make the story an even richer experience.”

The film was shot entirely in New York, both in Manhattan and upstate locations. “It was great fun to be able to work at home,” says Hallström, who has lived in New York for years. “I haven’t had that experience since I was making films in Sweden.”

In forging the look of the film, Hallström collaborated closely with his long-time director of photography Oliver Stapleton in their fifth film together. Like the director, Stapleton couldn’t resist Clifford Irving’s story. “I loved the script as I am fascinated by true stories that are also larger-than-life,” he says. “When fiction is based on a true story it can give it a real depth.”

The story and the era quickly inspired a lot of creativity. “Lasse was busy finishing Casanova during the prep period, so I had a lot of freedom to explore ideas before he was fully on board,” recalls Stapleton. “I came up with the idea of the black-and-white sequences during this time and also started looking at films from the period, including Tootsie for the comedy aspect, All the President’s Man as a political thriller and Three Days of the Condor for its atmosphere. The black-and-white segments were also influenced by Orson Welles’ A Touch of Evil.

He continues: “I also proposed to Lasse that we filter the whole film through a series of Tiffen FX filters and then sharpen it digitally later to give it some of that 70s softness. We talked about doing some of the sequences – especially those where the truth is in question – in neither color nor black-and-white but in an `in-between state’ that was desaturated from the main body of the film but not quite black-and-white either.”

Stapleton credits Hallström with giving him exceptional freedom to explore unorthodox visual concepts, pushing into entirely new territory for both of them. “I often heard the phrase from him, `be bold, be different,’” says Stapleton. “We wanted a very different feeling for this film – in a sense, I wanted to make the film look as if someone other than Oliver Stapleton had shot it! Creative renewal is an important part of any long-term relationship and has especially been so with Lasse.”

Another key component for Stapleton was the contribution of editor Andrew Mondshein. “Not only is he a great editor, he also has a very perceptive eye for the nuances of cinematography. He put in a lot of hard work on the digitial intermediate when I couldn’t be there and I couldn’t have had a better person do to stand in for me. Teamwork is one of the aspects of shooting films that I most enjoy and that was very much there on THE HOAX.”

Also keen to join the team was production designer Mark Ricker (The Nanny Diaries) who could hardly believe his good fortune when he read the screenplay for THE HOAX, which made it quite clear that this would be the kind of project to stretch a designer’s creativity. “Everything about it stood out,” he says. “There was an equal dose of being excited to work with this great period and also to be building so many unique sets., especially in the high-end New York publishing world.”

From the start Ricker and Lasse Hallström made the decision to create most of their own sets on stages at Steiner Studios in Brooklyn, which seemed to suit the tone of the film. “There’s a lot of layers to this story,” Ricker explains. “There are flashbacks, hallucinations and stories within a story, and all these things have different looks, so the design was very much a part of that collaboration.”

Clifford Irving’s journey takes him not only into the corridors of power at McGraw-Hill but into swanky hotel rooms, the Pentagon, the Library of Congress, Las Vegas and the Bahamas, each of which Ricker created in New York. “It was just vast and it was fascinating for me to go to all of these places in my head and then try to make them a reality,” he says. “The great thing about building sets is that you can control where the walls are and how everything’s set up so it’s an open canvas.”

Ricker especially had fun building the interior of McGraw-Hill’s offices from scratch to give it an atmosphere that really brings to life Clifford Irving’s audacity in the face of power and moeny. The 70s-era look is sleek, bright and rife with the visual shock of a publishing office without a single computer – lined instead with electric typewriters.

They also made a switch with the exterior of the building. In 1971, the McGraw-Hill offices of were housed on 42nd Street, atop a classic Art Deco skyscraper, but the locale production logistically impossible to shoot. Since McGraw Hill would move shortly thereafter to Rockefeller Center, the production used that location for such key sequences as when Clifford Irving awaits for Howard Hughes to supposedly arrive in his helicopter (a scene that never happened in real life.) “I really liked the look of the newer offices, they’re slick and stylish and a lot more fun to deal with,” says Ricker.

Wherever possible, Ricker also mixed in authentic touches. For example, the production obtained the rights to use Edith Irving’s real paintings for the scenes that take place in the Irving household. For Lasse Hallström, Ricker’s sets provided both the flexibility and the link to reality he was seeking. “I was really impressed with how atmospheric his interiors are. Yet, there’s nothing flashy about his work, it’s simply very, very real,” observes the director. “He has a great eye and he was able to recreate the 70s with very keen and original details.”

Adds Leslie Holleran: “Oliver and Mark did a fantastic job together with Lasse. They found a different of looking at this world of the 1970s that is very natural and real and yet you feel as if it is happening right now.”

Also helping to evoke the details of the 70s era is costume designer David Robinson, whose work has ranged from the comedy hit Zoolander to Tamara Jenkins’ indie The Savages. Robinson was so intent on getting the job, he showed up for his initial meeting with Lasse Hallström having already compiled masses of research. “I brought in so much research that he simply could not say no,” laughs Robinson. “I was just very excited about creating a reality for these characters.”

The two hit it off creatively right away. “Lasse explained that he wanted the audience to feel like they were witnessing these events happening and didn’t want to feel the hand of a designer at work,” Robinson recalls, “and that was already my approach – to create the clothing as if you had just run into these people and this is what they were wearing.”

Robinson was also excited to be tackling a fresh subset of the 70s scene – inside the publishing world. “When you think 70s, you usually think bell bottoms, wide ties and paisleys, but there’s a whole different set of codified dressing behaviors inside the publishing world,” he explains. “If you look at photos of publishing executives in the New York Times of 1971, you see people still wearing Brooks Brothers suits from the 60s with narrow ties and button down shirts. So we mixed that kind of look with younger editors who are more swinging and groovy, with the wide lapels and long collar points.”

As for Clifford Irving, Robinson describes the look he gave to Richard Gere as “rather preppy, with lots of button downs and cardigans.” It was largely based on historical photographs of the real Irving. “A lot of the work with Cliff was reproducing ties and suits he actually wore,” states Robinson.

One of Robinson’s most thrilling challenges was designing the costumes for the glamorous Black & White Ball – which was based on Truman Capote’s 1966 Black and White Ball in honor of Washington Post editor Katherine Graham, famously attended by such hand-picked luminaries as Candace Bergen, Norman Mailer, Frank Sinatra and Mia Farrow. The real party did not include Clifford Irving on the guest list – but in the film, amidst all the intoxicating power and beauty, it is where the character of Irving begins to seal his fate.For Robinson, the fun was in recreating that sense of Irving among the most posh and fabulous elites.

“From a costume perspective, there was just so much variety to play with,” says Robinson. “We have some people who are very avant-garde and then you have others looking like they’re still in the Kennedy Era, with teased hair and empire-waisted gowns,” he notes. “We also recreated costumes and masks for the celebrities at the ball, including Katherine Graham, Candace Bergen and Mia Farrow. “

Perhaps most fun for Robinson was the dress designed for Hope Davis’ editor character. “Her dress is sort of riffing on Yves Saint Laurent’s African line from that year,” Robinson explains. “It’s very balls out with its African flavor and in keeping with her character – and Hope totally knew how to wear that dress.” He also has a soft spot for Julie Delpy’s dress “I thought the dress for Nina was just the perfect, princessy gown to wear to a ball, and I think Julie felt very flattered and attractive in it, because she become so stately and classy,” he says.

Another joy was dressing Stanley Tucci as Shelton Fisher. “Stanley’s character was a total blast,” says Robinson., “because this is a man who really knows his suits. And once we started dressing him, Stanley really got into it and channeled that even more..”

For Lasse Hallström, the clothing and all the other design elements helped to further blur the lines between the real world of power and the fantasy world of storytelling that Clifford Irving melded together. Sums up the director: “There was a very loose atmosphere and a lot of joyous exploration by the cast and crew. The film takes full advantage of artistic freedom while remaining true to the essence of Clifford Irving’s hoax.”

# # #

A Note on Clifford Irving and Watergate

In THE HOAX, Clifford Irving’s story of bold deception collides with one of the biggest scandals of power and corruption that has ever hit the U.S.: the ill-fated and illegal break-in of the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters at the Watergate Hotel – an event that would ultimately bring down the administration of President Nixon and permanently change American politics.

Did Clifford Irving truly find himself, however unwittingly, as a player in the back-story of Watergate? Considerable evidence unearthed by producer Josh Maurer suggests he did. According to such sources as Senate Watergate Committee hearings, FBI files and the memoirs of former members of Nixon’s administration, Nixon either read the galleys or was provided a summary of Irving’s unpublished book prior to June, 1972 – and erupted with concern over the fact that it highlighted shockingly accurate, theretofore top-secret information about illegal loans Howard Hughes had made to Nixon’s brother in exchange for favors. “We were stunned — and intrigued — to discover the very real probability that this hoax prompted Nixon’s terror of a connection between the DNC and Howard Hughes,” says producer Leslie Holleran.

The arrival of Irving’s soon-to-be-published book coincided with a time when Nixon had ample reason to fear that the powerful Hughes, under pressure of government lawsuits and angry over nuclear testing in Nevada, might seek to destroy his administration. Adding fuel to the fire was the discovery made by “the Plumbers” in the first Watergate break-in that DNC Chairman Lawrence O’Brien was on Hughes’ payroll. While no one will ever know how each of the many pieces of the puzzle factored into Nixon’s mind when he ordered the second break-in at the Watergate Hotel, it appears that the revelations in Irving’s forthcoming book were involved in the mix.

For example, in former White House Counsel John Dean’s book Blind Ambition he reports that: “[Robert Bennett] came to see me. He wanted me to have the Justice Department investigate Irving. I passed, but I remember that Haldeman [H.R. Haldeman, White House Chief of Staff] wanted to find out what was in the Irving manuscript. And somebody from the White House got a copy from the publisher.” Dean also quotes former Chief Counsel Charles Colson as saying: “Everyone figured Maheu [referring to Robert Maheu, a former FBI and CIA employee who was a key figure inside Hughes’ organization] might have supplied Irving with information one way or another…

The way I see it, Haldeman was worried about that coming out. Another messy Hughes scandal.” FBI files obtained through the Freedom of Information Act further confirm that FBI director Edgar J. Hoover was sending Haldeman reports on the Irving affair. This is further corroborated by Senate Watergate Committee testimony, such as this confession from Nixon’s political adviser Charles “Bebe” Rebozo: “The concern was principally any disclosure that the president had received Hughes’ money… I didn’t want to risk even the remotest embarrassment about any Hughes connection to Nixon.”

The widely praised book Citizen Hughes: The Power, The Money and The Madness by Michael Drosnin, further builds the central thesis that Nixon’s driving concern was that the Democrats were being fed scandalous information by Howard Hughes’ inside organization – leading back to Clifford Irving’s book and its highlighting of the illegal loans.Finally, in his own memoirs (RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon) former President Nixon writes: “.There was new information… that the Hughes organization might be involved. And there were stories of strange alliances.

One of the great true-life ironies of Clifford Irving’s story is that he found himself, however unintentionally, in the middle of this realm of strange alliances – all based on an alliance between himself and Howard Hughes that never happened!

Fact V. Fiction V. Hoax

FICTION: In the film, McGraw Hill employees and Clifford Irving are seen waiting for a helicopter purportedly holding Howard Hughes to land

FACT: There were never preparations made for a helicopter landing at McGraw-Hill

HOAX: Clifford Irving definitively reported to producer Josh Maurer that it was a fact, that was not included in the book, but later suggested it was fanciful.

FICTION: In the film, McGraw-Hill passes on Clifford Irving’s latest manuscript

FACT: Irving actually had a 4-book deal at McGraw-Hill at the time of the ruse

HOAX: Lasse Hallström notes that McGraw-Hill had previously published Irving’s book Fake!, about forger Elmyr de Hory, which perhaps should have tipped them off to his fascination with the false

FICTION: In the film, Irving is seen attending Truman Capote’s celebrity-studded Black & White Ball

FACT: The real Black & White Ball took place in 1966 and Clifford Irving wasn’t there

HOAX: Costume designer David Robinson put Richard Gere in a black cat-mask, just like Frank Sinatra wore at the real ball

FICTION: In the film, Irving lives in Upstate New York and travels across the United States preparing his fake book on Howard Hughes

FACT: Irving’s primary residence was Ibiza, Spain during 1971

HOAX: Screenwriter William Wheeler condensed many events and dramatized interactions that actually took place via letters and phone calls-if Ibiza was used in the film, notes Wheeler, “the entire movie would’ve been a 90-min shot of a man on a telephone in Spain.”

FICTION: In the film, a hotel in the Bahamas is evacuated of all visitors at Howard Hughes’ insistence

FACT: Hughes was living at Paradise Island in the Bahamas but no such incident was ever reported

HOAX: The filmmakers wanted to emphasize a reality – the Hughes was obsessed with heavy security and avoiding the public eye. There are stories that he once insisted the lobby of Las Vegas’ Desert Inn be empty when he entered it.

FICTION: In the film, Irving steals portions of Noah Dietrich’s Howard Hughes book right out from under him in his own house

FACT: Clifford Irving actually got access to Dietrich’s manuscript (published as Howard: The Amazing Mr. Hughes) through an intermediary, but when told he had to read the one and only copy privately and return it, he had it Xeroxed without permission so that he and Dick Suskind could use the reproduction as further information for their book

HOAX: The scene in the film plays on the way Irving copied the manuscript illicitly

FICTION: In the film, Dick Suskind is seen having an affair with a hooker

FACT: The loyal Suskind never had such an affair

HOAX: The filmmakers took Suskind even deeper into Clifford Irving’s world than he really went to push the dimensions of their friendship.

Hoaxed! A Brief Guide to Famous Media Hoaxes

THE CARDIFF GIANT HOAX: One of the earliest and greatest media hoaxes of all time, the Cardiff Giant Hoax began in 1869, when workers digging on a farm in Cardiff, New York unearthed a mysterious stone fossil in the shape of a ten-foot tall man. When the newspapers were alerted, controversy exploded, with some “experts” speculating the find was a “petrified human,” perhaps from Biblical days when giants roamed the earth. Meanwhile, farm owner William C. Newell began charging admission to see the colossus and soon sold ¾ of his interest in the fossil to a syndicate in Syracuse, New York for $30,000. Two months later, as the fossil began a multi-city tour, it was revealed that Newell’s distant relative George Hull, a cigar manufacturer from Binghamton, had perpetrated a hoax in order to prove how gullible Americans really were. The Cardiff Giant remains on display to this day at the “Farmer’s Museum” in Cooperstown, New York.

THE PILTDOWN MAN HOAX: In 1912, Charles Dawson of Piltdown, England claimed to have made an earth-shattering discovery: the fossilized skeleton of a creature that was the link between apes and humans. The world was riveted. Some anthropologists even staked their careers on the discovery. It wasn’t until 1953 that scientists realized that the famed skeleton was a complete fake, crafted out of different animal parts from all around the globe that were simply treated to look ancient. Today, the hoax is still considered one of the most famous frauds in the history of science.

THE VERMEER HOAX: After World War II, authorities found what they thought was a new painting by Dutch master Johannes Vermeer in the collection of Nazi leader Hermann Goering. The sale of the painting was traced to one Hans Van Meegeren, a Dutch painter, who was immediately arrested for collaborating with the enemy. But Van Meegeren had a twist to his story – he explained that he had actually forged the Vermeer, and to prove it, he painted another exact replica in his jail cell! Van Meegeren would soon go down as one of the world’s great copycat artists. It was eventually determined that he had forged 14 additional Vermeers, all of which were considered to be authentic masterpieces, earning millions of dollars. His forgeries were so good that some experts continued to argue the paintings were real even after he confessed his hoaxes!

THE STONE AGED TRIBE HOAX: In the 1970s, Manuel Elizalde, Ferdinand Marcos’s Cultural Minister, told the world he had made “first contact” with an incredible, newly discovered tribe in the Philippines. They were known as the Tasaday and it was claimed they were astonishing relics of humankind’s ancient past – so primitive that they lived in caves, wore no clothing, had never even heard of agriculture and had no knowledge of any technology beyond the Paleolithic Stone Age. National Geographic and news networks sent cameras but few scientist were able to see them. But after the fall of Marcos, those who came to report on and study the Tasaday found them wearing t-shirts and jeans and using plenty of modern tools. The tribe members subsequently admitted they had been paid to act more “primitive” by Elizalde, discarding their clothes and using fake stone tools.

THE BOSTON MARATHON HOAX: In 1980, the first woman to cross the finish line at the Boston Marathon shocked race-watchers not only because she set a new course record but because she was a complete unknown. Her name was Rosie Ruiz and when she broke the ticker-tape, she appeared barely to have broken a sweat – as it turned out, for good reason. An investigation and eyewitness reports determined that Ruiz had likely jumped into the race ½ mile from the finish line. Although she maintained her innocence, second place finisher Jackie Gareau was named the new champion.

THE HEROIN ADDICT HOAX: One of the first of many hoax scandals that would strike at the heart of journalism took place in1980. That year, Washington Post reporter Janet Cooke was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for her searing, heartbreaking story about an 8 year-old heroin addict named “Jimmy.” When Cooke was asked to reveal the child’s real identity so that authorities could help him, she refused, saying it could endanger her life.But under increasing pressure, Cooke ultimately admitted that “Jimmy” was largely fictitious, based on a child rumored to exist but whom she had never met. When Cooke was interviewed for a GQ article, the movie rights to the piece were sold for $1.5 million.

THE HITLER DIARY HOAX: One of the biggest news stories of 1983 exploded when the German newspaper Der Stern claimed to have a diary kept by Adolph Hitler during the key years of 1932-1945. It sounded too good to be true – and it was. The document had supposedly been pulled from the wreckage of an airplane and preserved for decades by an East German General. As a bidding war for the rights to publish ensued, Der Stern claimed it was 100% certain that the diaries were not forged. But when experts finally had a chance to review the diaries, they found not only a forgery, but an embarrassingly bad one. Even the paper the diary was written on was dated as post-War. At last, Der Stern admitted it had been duped by West German memorabilia collector Konrad Kujua, who wrotethe diaries himself, and a reporter named Gerd Heidemann, who nearly made off with the $9.9 million marks paid for the faux diary.

THE MILLI VANILLI HOAX: The German band Milli Vanilli debuted with a bang in the late 1980s, winning the 1989 Grammy Award for Best New Artiss after their hit singles “Blame It On The Rain” and “Girl You Know It’s True” rose to the top of the charts. But fans were crushed to later learn that the duo of Robert Pilatus and Fabrice Morvan were frauds who had no musical talent whatsoever. Their entire act was a sham of lip-synching to the music of a less attractive band named Numarx. Milli Vanilli were stripped of their Grammy. Although they tried to revive their careers by releasing their own album, they could never recover from the scandal.

THE ALIEN AUTOPSY HOAX: In 1995, a documentary aired on the FOX network purporting to be an authentic film of a post-mortem on an alien body from Roswell, New Mexico, 1947. The producer of the film, the London-based video entrepreneur Ray Santilli, claimed at the time that the footage had been authenticated by Kodak as real. Many elements of the film caused skepticism, but in 2006 the controversy came to end when Santilli confessed and when John Humphreys, an English sculptor and special-effects artists, admitted to creating the “alien” for the film and playing the pathologist performing the autopsy. The story inspired the 2006 comedy film Alien Autopsy.

THE HOLOCAUST SURVIVOR HOAX: In 1998, the publishing world was stunned with another hoax when it was revealed that a prize-winning, critically acclaimed Holocaust survival memoir was actually a piece of out-right fiction. The book Fragments: Memories of a Wartime Childhood, written by Binjamin Wilkomirski supposedly about his harrowing childhood in Nazi-occupied Latvia, was so chillingly real it was called “stunning” by the New York Times when it was first published in 1995. But even more stunning was the fact that a few years later a Swiss journalist revealed that Wilkomirski was born in Switzerland, not Latvia, and his stories were almost certainly made up. Wilkomirski continued to insist he was a real Holocaust survivor- and the controversy raged on such television shows as “60 Minutes.” In 1999, an investigation by Wilkomirski’s literary agency concluded that Wilkomirski’s writings were in direct contradiction to the facts, but to this day no one knows for sure whether Wilkomirski intentionally perpetrated a hoax or was a simply a deluded person who believed his own stories.

THE JAMES FREY HOAX: Memoir writer James Frey sold more than 3 million copies of his supposedly true tale of harrowing addiction and hard-won recovery, A Million Little Pieces, and received a big boost when television powerhouse Oprah Winfrey recommended his book. But in 2006, reports began to circulate that many of the incidents in Frey’s book were false or wildly exaggerated. After an intense media frenzy, including a public inquiry on “The Oprah Winfrey Show,” Frey’s publishers, in an unprecedented move, offered a refund to readers who felt they had been defrauded.

The Hoax (2007)

Directed by: Lasse Hallström

Starring: Richard Gere, Alfred Molina, Marcia Gay Harden, Hope Davis, Stanley Tucci, Julie Delpy, Susan Misner, Mamia Gummer

Screenplay by: William Wheeler

Production Design by: Mark Ricker

Cinematography by: Oliver Stapleton

Film Editing by: Andrew Mondshein

Costume Design by: David C. Robinson

Set Decoration by: Carol Silverman

Art Direction by: Mario Ventenilla

Music by: Carter Burwell

MPAA Rating: R for language.

Distributed by: Miramax Films

Release Date: April 6, 2007

Visits: 78