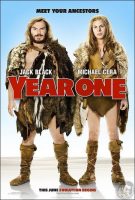

Tagline: Meet your ancestors.

Zed, a prehistoric would-be hunter, eats from a tree of forbidden fruit and is banished from his tribe, accompanied by Oh, a shy gatherer. On their travels, they meet Cain and Abel on a fateful day, stop Abraham from killing Isaac, become slaves, and reach the city of Sodom where their tribe is now enslaved. Zed and Oh are determined to rescue the women they love, Maya and Eema. Standing in their way is Sodom’s high priest and the omnipresent Cain. Zed tries to form an alliance with Princess Innana, which may backfire. Can an inept hunter and a smart but slender and diffident gatherer become heroes and make a difference?

Year One is a 2009 American comedy film directed by Harold Ramis, and produced by Judd Apatow. The film stars Jack Black and Michael Cera. The film was released in North America on June 19, 2009 by Columbia Pictures, where it received negative reviews from critics and underperformed at the box office. The film would be Ramis’ last as an actor, writer, and director before his death in 2014.

Year One opened at #4 at the US box office in its opening weekend.[12] The film eventually grossed $43,337,279 in US ticket sales, and a further $19,020,621 worldwide, for a total of $62,357,900, and when compared to its $60 million budget, Year One was a box office disappointment.

About the Production

In the beginning, there was nothing. Then, Harold Ramis had an idea. “I was thinking about two things in comedy that I love,” says the writer-director-producer. “One was Mel Brooks’ Two-Thousand-Year-Old Man, and the other was an improvisation I staged 35 years ago with John Belushi and Bill Murray. Bill played a Cro-Magnon man with a completely hip and contemporary vibe, and John played a Neanderthal Man as an idiot. For this movie, I had those inspirations in mind when I thought it would be really interesting to put someone with a contemporary consciousness in an ancient setting.”

That’s when he hit upon the idea for Year One. In his words: “Two innocent, know-nothing Paleolithic hunter-gatherers, Zed and Oh, get kicked out of their Garden of Eden paradise and begin a search for what life is all about.” Taking that trek is none other than Jack Black. “Zed is living a very tribal lifestyle in his primitive village with hunters and gatherers,” he says, “but he’s wondering if there’s more to life than just hunting, gathering, and sleeping.”

Joining Zed on the first road trip in history is Oh, played by Michael Cera. While Zed is aggressive in his pursuit of meaning, Oh dragged into the unknown kicking and screaming. “We called this character ‘Oh’ because he’s completely reacting to life and everything in life that is a threat to his character — and he does suffer a lot in the movie,” the director chuckles. Shepherding the project is producer Judd Apatow, who teams with Ramis for the first time.

“It was a dream come true to get to work with Harold Ramis. Some of the highlights of my childhood were the days when I went with my friends to see Stripes, Ghostbusters, Caddyshack and Animal House. He is obviously one of my main inspirations. It has been a real honor to get to see him work up close. Sometimes I would be watching Harold work and think to myself, ‘Oh, this is where we got all these funny comedy team relationships from.’ His work is hardwired into our brains.”

To write the screenplay, Ramis turned to a writing team that he knew well. Gene Stupnitsky had once served as Ramis’s intern, and Lee Eisenberg had been a waiter at one of Ramis’s favorite restaurants on Martha’s Vineyard. Some years ago, the two met as production assistants on one of Ramis’s films, started writing together, and then found better gigs: writing and executive producing the hit series “The Office.”

“I really didn’t want to write alone,” Ramis explains. “Who could I get who would really push me? They were ready for the challenge, full of ideas, and very professional. We had a great time.” As the characters fleshed out on the page, the director was cognizant that the actors cast would finally bring them to life. In his mind’s eye, he saw Jack Black as his hero, Zed. “The whole time, I was thinking, ‘Wow, this could be great for Jack Black,” the director reminisces. “Jack really knows how to be silly and take big chances with comedy. He’s incredibly sharp; there’s a really great articulation to what he does.”

The Look Of The Year One

For Production Designer Jefferson Sage, Year One marks a reunion with both Harold Ramis, having had worked as Art Director on Analyze This, and Judd Apatow for whom he designed The TV Set, Knocked Up, Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, and the upcoming Funny People. Sage was immediately struck by “the chance to create a period world that had a lot of distinct references to history. Year One is essentially a road movie, where they encounter very specific different worlds.”

Sage went about creating these worlds by first researching the different periods represented in the story. “We collected a lot of visual research. At the beginning, I made a big book of research and sent it to Harold. It immediately gave us all a common reference point in terms of what the movie should look like.” Together with Ramis and Alar Kivilo, the director of photography, Sage decided to go for a style that sticks as closely to reality as possible, rather than give Zed and Oh a stylized or comedic setting.

“The comedy comes from these odd characters and very contemporary kind of sensibilities against the hard edges of that world,” he explains. The worlds that the story called for include a Paleolithic stone-age village where the main characters Zed, Oh, Maya, and Eema are introduced; the farming hamlet; a desert setting, where the characters discover the new phenomenon of the marketplace; and, finally, the broad and wild city of Sodom. “Part of our job was to make each of those distinct and give them their own set of rules that could help differentiate one from the next. Each one suggests its own palette, color and textures,” says Sage. “For example, in the Paleolithic village, one of the rules is there’s no metal because at that time, these guys haven’t discovered metal yet.” The biggest challenge, and biggest set, was Sodom. “When I read the script, I thought, ‘That’s the biggest set I’ve ever seen, let alone worked on,’” says Sage.

Sage would end up building the entire city on five acres of land: three separate streets, all dressed with market vendors, houses, doorways and windows; three separate squares; a blind alley connecting two streets; a palace with a courtyard; a Ziggurat (a terraced, pyramid temple); a royal pavilion; and a sacred sacrificial space. It was the equivalent of 46 separate sets. “I think our Sodom is reasonably authentic,” says Sage.

“We looked at fortified cities from similar periods and studied details about them, and then we put those together into our own kind of vision of Sodom.” But once they had done the research and were well-schooled in the look of the era, it was time to branch out. “At a certain point, I put the research down, and we began to create our own rules.” An example of this is the enormous bull’s head that served as a centerpiece for the main square. Says Sage, “I didn’t find a specific idol of the specific size and scale we use in the film, but the bull’s head was very common throughout religious cultures in that area for thousands of years; we found representations of that in sculpture and friezes and in jewelry.

We made it a 27-foot-tall fire breathing stone idol that would work as well for the script – they’re sacrificing virgins and tossing them inside. Many idols existed at the time, but it seemed like the bull, with its commanding, domineering face, made sense dramatically.” With Sodom designed, the question became how the filmmakers would light the massive set. Before construction could begin, they had to situate the set on the site. Keeping in mind that the set would be shot in the winter months in Louisiana, the filmmakers planned out the details.

“We took the plan of the city and rotated it to see what gave us the most advantageous sunlight into the city. We wanted the sunlight to fall a certain way across the Ziggurat, across the plaza and into the streets. At one point we actually took our big model and used a single light bulb and rotated that so we could actually study how the sunlight and the angles that would typically be at during the months of January and February here would actually look,” says Sage. Having determined the best position for the set, construction began in earnest. Astonishingly, they completed construction of the city in ten weeks.

About The Costumes

Costume Designer Debra McGuire was delighted to tackle the historical elements for the story. “I don’t know if we can top this,” she says about the experience. “For me, as a designer, it really gets very exciting and creative. It’s been an adventure and exactly what I love to do most. I love to do research.”

Indeed, that research enabled her to provide a solid background for the actors’ comedy. “I always find on doing these that the closer you get to reality, the funnier it is,” McGuire continues. “You have to let the comedy be the comedy. We can never try to make clothes funny and distracting.”

Just as the production design team envisioned a separate look for each of the film’s sections, so too did the costume designer. “We divided all of the different periods by palette and color,” says McGuire. “What I try to do through every period is to do something with the palette that will resonate with the audience. We do that by having Zed and Oh experience an evolution in the creation of color and fabrics.”

The film begins with Zed and Oh in their primitive village. “We’re dealing with leather and skins and beads in that period and we had to make everything,” McGuire says.

One of those costumes in this period was Zed’s skunk pelts. “I think that was the most inspired costume – all the other hunters have bear hides and wolf coats. I just got my stinky skunk pelt. That’s what Zed was able to hunt down and capture,” says Jack Black. “It says a lot about my character.”

“I’ve worked before with Jack Black and Michael Cera on different projects. That really helps me to understand the body language and the way they move – although I’ve never dressed them in skirts or skins before,” McGuire laughs. “They loved and embraced everything. They are so easy to work with because they really understand how important costumes are and I know that a lot of the primitive costumes were difficult because there’s not much there. These are actors who never complain.”

In addition to costuming the main characters, the wardrobe department created outfits for 60 to 100 background artists as well. “Everything had to be aged and dyed. Everything in that period is all natural fibers and dyed so it matches the wheat and surrounding colors. Footwear had to be made from scratch. All the jewelry was made.”

The clothes also had to be functional for the main characters. “It’s all tied together very primitively, but they do a lot of action in them,” notes McGuire. “We were sure to get these wonderful insoles to go inside the shoes and built around them. The costumes have to withstand the wear and tear, so we did do multiples for everything.”

From the primitive village, Zed and Oh soon find themselves with Abraham and his followers. The costumes change, McGuire explains: “We see more wovens, stripes, head gear.”

With the new palette, McGuire took some liberties. “In reality, the people in this period had very minimal color. Color came from a shellfish – you’d have to have millions of fish to dye something blue. It would have been impossible for them to have used that amount of color that I used. Even though it’s more fantasy than reality, we decided that their world would have a lot of color and would introduce the color blue to the film.”

As the film progresses, McGuire slowly opens the wardrobe palette. “The marketplace scene which is where all the cultures come together,” notes McGuire. “This is the first time that we see the melting pot of the world at that time, where we see silks and new colors and fabrics. By the time we get to Sodom, we have a all these magnificent fabrics and jewelry and a very opulent world.”

When Zed and Oh get to Sodom, they are introduced to a world of saturated reds, blues, and purples. The queen was outfitted in gold metal mesh and brilliant turquoise. The women of the court and the virgins called for a very, very soft palette.

“I used a lot of white and gold,” McGuire says. McGuire contrasted the soft female energy and soft palette with the deep colors of the members of the clergy. “I took the priest cast and divided them into these beautiful lush purples and raspberry colors. For the ministers and all the people below, I came up with a palette very cinnamon and persimmon.”

Oliver Platt as the high priest was singled out. “He wears a crown with three levels of opulence,” says McGuire. “Not only is it completely jeweled, but my idea was that all of the priests under him would have a lower level of crown. The next level of priest has two and next level has one and then the acolytes have nothing.”

But McGuire didn’t stop there. From crown to boot, the high priest is covered in luxury. “Oliver is bigger than life,” says McGuire. “He’s six-foot-four, and he’s in gold platform boots – that was right in the script. We call them the primitive disco boots; they’re made out of gold leather. His crown is probably 20 inches.

He’s wearing a long velvet cape with a gold embossed capelet. Then a gold tabard – his is full body and it’s beautiful embossed fabric. Then I have a skirt over a skirt – the under skirt is velvet and is bubbled at the bottom. He also has a very opulent necklace. His hair is curled and outrageous and his eye make-up is extraordinary.” In such a costume, with weather reaching the 80s, Platt could have been in for a rough time.

As Platt explains, “On a hot day, watching those virgins bathing themselves, it could be a bit of a challenge – but everybody needs to sacrifice something. The virgins sacrifice their lives. I sacrificed a little sweat to look fabulous. And trust me, I look fabulous.”

No actor had it tougher than Cera. For starters, his close-cropped cut is covered with a long, shaggy wig. “I’m definitely not used to having long hair,” he says. “it was in my face and got in my mouth all the time. And if I had a bagel with cream cheese, the hair would just stick there… it was disgusting.”

But the hair was the least of Cera’s troubles. “It was tough to get the wig glued on every day, but getting painted gold was much, much worse. Getting painted gold was the most uncomfortable thing I’ve ever done for a job,” he says.

“It was awful. And it took forever to get it off – I’d take several showers and then still see gold on my ankles. I couldn’t lift my arms above my shoulders or it would feel like I was ripping my skin off at the armpits. It was excruciating. There’s another point in the movie where I’m hanging upside down; I thought that was bad, but I’d do that in a heartbeat over getting painted gold again.”

Working in tandem with other department heads was crucial for Year One as there was little reference material for several of the time periods. “Jeff Sage and I were always on the same wavelength,” says McGuire. “Everybody just seems to be in sync. The hair designer, Yvonne Kupka and I go back too many years to mention. We were thrilled to have this project to create together.”

For Year One, the hair design became integral to the costuming – much more so than in contemporary stories. “We talked intensely about every character. It’s very unusual and wonderful to have a close collaboration with hair and make-up and wardrobe, but it makes all the difference in the world. Yvonne’s hair designs are so spectacular; she came in early and see my costumes, and I brought her a lot of fabric to use in the hair. She put together her own stash of jewels for the hair.”

The final element for McGuire was jewelry, which was used, in various forms, in each time period, ranging from crude necklaces of animal teeth in the Primitive landscape, to spectacular showpieces in Sodom. “Jewelry was very important to me,” she says. “It was as if these pieces were made for Sodom. We got hundreds of pieces and used almost all of them. Most of them are made out of different metals, real stones, glass stones. Some of them are hand-wrought. They’re very, very noticeable – especially on the Queen and the King and Oliver.”

The Year One (2009)

Directed by: Harold Ramis

Starring: Jack Black, Olivia Wilde, Michael Cera, Christopher Mintz-Plasse, Oliver Platt, David Cross, Vinnie Jones, Juno Temple, June Diane Rapheal, Eden Riegel

Screenplay by: Harold Ramis, Gene Stupnitsky, Lee Eisenberg

Production Design by: Jefferson Sage

Cinematography by: Alar Kivilo

Film Editing by: Craig Herring, Steve Welch

Costume Design by: Debra McGuire

Set Decoration by: Dorree Cooper

Art Direction by: Richard Fojo

Music by: Theodore Shapiro

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for crude and sexual content throughout, brief strong language, comic violence.

Distributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: June 19t, 2009

Visits: 53