About the Production

Thematically, Moore and Lloyd’s series explores many political and ethical notions of continuing relevance in today’s world. “The principal message of the original is that every individual has the right to be an individual, and the right – and duty – to resist being forced into conformism,” comments Lloyd. “V resists by directly attacking government installations and murdering the regime’s supporters. So it’s not just a story about a battle against an evil tyranny, but a story about terrorism and whether terrorism can ever be justified – and that’s something we have to try to understand if we’re ever to solve the problem of it in the real world.

Acclaimed writer / directors Andy and Larry Wachowski, the inspired minds behind the revolutionary Matrix trilogy, were fans of Moore and Lloyd’s original work, and first wrote a screen adaptation of the graphic novel in the mid-1990s, before embarking on the Herculean task of filming the Matrix trilogy. During post-production on the second and third installments of The Matrix, the Wachowskis revisited the Vendetta script and brought it to the attention of their first assistant director, James McTeigue, with whom they had worked on all three Matrix films.

McTeigue had been directing commercials at the time and was looking to transition to feature films. “We were in post-production on Revolutions when Andy and Larry first gave me a copy of V for Vendetta,” remembers McTeigue. Intrigued and excited about the themes of the graphic novel, he shared the Wachowskis’ view of its relevance in the current political landscape. “We felt the novel was very prescient to how the political climate is at the moment. It really showed what can happen when society is ruled by government, rather than the government being run as a voice of the people. I don’t think it’s such a big leap to say that things like that can happen when leaders stop listening to the people.”

At the time, the Wachowskis had just reached the end of a 10-year odyssey with the Matrix films and were not prepared to immediately jump back into directing. As McTeigue explains, “Ten years is a long time to spend on anything, and making films takes a lot out of you. I think Andy and Larry wanted the film to be made now, but wanted to take a back seat for awhile.”

So the Wachowskis and producer Joel Silver offered their longtime colleague the opportunity to direct V For Vendetta, surrounded by many of the Wachowskis’ other key collaborators, such as producer Grant Hill, production designer Owen Paterson, visual effects supervisor Dan Glass and stunt coordinator Chad Stahelski, with the brothers collaborating as producers and writers.

In returning to the script, the Wachowskis went back to their original draft and set about making revisions. As McTeigue recalls, “Their original version was a really good adaptation, but it was almost a blow-for-blow retelling of the graphic novel. We thought it would be good to move the story forward in time, setting the flashback portion in the 1990s and projecting the present-day timeline into the future around 2020.”

Other key revisions included streamlining Moore and Lloyd’s storyline, altering Evey’s background and making her older than in the original material. “The graphic novel is quite sprawling and has a lot of characters,” McTeigue points out. “Some of those characters had to be amalgamated or taken out, but all the while we made sure we were adhering to the themes and integrity of the graphic novel.”

The adaptation process was made easier by the cinematic way in which Lloyd and Moore constructed the original novel, with traditional ‘thought balloons’ replaced with captions, and rectangular panels substituted for splashy layouts. Lloyd feels the Wachowski screenplay adaptation was a good representation of the original. “I never had a purist concept of Vendetta as just a comic,” he remembers. “It always felt like an idea that could be transposed to other forms of media. In any of my work, the only expectation and desire is that the spirit and key elements are retained and the same essential message is captured.”

The filmmakers were adamant that V’s enduring mystery remain intact, and in reverence to Moore and Lloyd’s novel and richly drawn character, in the film V’s horribly burned and disfigured face remains hidden behind a mask that carries the visage of Guy Fawkes, another legendary saboteur who came to a violent end over four hundred years ago…

On November 5th, 1605, Fawkes was captured beneath the House of Lords with 36 barrels of gunpowder hidden beneath pieces of iron and firewood. While tortured, Fawkes revealed an audacious conspiracy to blow up the English Parliament and King James I on a day when the King was due to open the parliamentary session.

Fawkes was one of 13 disaffected Catholics who hoped to end James’ persecution of English Catholics. The intent was to create chaos and disorder in the country from which, it was hoped, a new monarch and political regime sympathetic to the Catholic cause would emerge. A veteran soldier, Fawkes was highly proficient with gunpowder and so became an integral part of the group’s scheme.

A cellar underneath the House of Lords was acquired by the conspirators where they stored explosives and awaited the opening of Parliament. However, as more accomplices were drawn into the plot, secrecy was endangered and an anonymous letter to Lord Monteagle, a Catholic, warning him to stay away from the opening of Parliament, brought about the plan’s demise. On the night of November 4th, Fawkes was caught in the cellar, arrested and brought before the King. Succumbing to grueling torture, his silence was broken and the ambitious plan disclosed. Fawkes and the other members of the group were publicly hanged, drawn and quartered, as was customary for traitors at that time.

Every year across England on November 5th, bonfires blaze and fireworks light the sky in celebration of the foiling of Fawkes’ plot to overturn King and government. Fawkes masks are sold throughout the country and effigies of the conspirator, or “Guys,” are burned. When Alan Moore and David Lloyd were originally conceiving the character of V for their graphic novel V for Vendetta, Guy Fawkes provided inspiration for the comic’s political context. Like Fawkes, V hopes to create chaos from which the country’s insidious regime will fall.

There is a dramatically disturbing aspect to V’s use of the Guy Fawkes mask as well. “Guy Fawkes masks have a kind of eerie look because of their smile,” Lloyd notes. “It makes the character look bizarre and threatening at the same time – the last thing you expect from someone coming to kill you is a smile on their face.”

In V For Vendetta, the man behind that eerily grinning mask is multifaceted actor Hugo Weaving, whose impressive and varied career includes starring roles as the deadly Agent Smith in the Matrix trilogy and as Elrond in all three installments of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, as well as memorable turns in the indie sensations The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and Proof.

“V wants to continue what Guy Fawkes and the plotters of November 5th weren’t able to do,” says Weaving. “He wants to blow up the Houses of Parliament because he believes, as they believed, that they have become a symbol of tyranny.”

V sees himself as fated to disrupt a system that he views as cruel and unjust. “His deep desire to serve the greater good is inextricably tied to his obsessive quest for personal vengeance,” says Silver.

In the midst of his quest to free the people of England from their fascist leaders, V is on a very personal mission to wreak vengeance on those who imprisoned and tortured him, and in doing so, created a monster. One by one he is systematically eliminating these enemies, leaving a single Violet Carson rose as his calling card at the scene of each murder. Possessing deeply-held convictions, heightened by this bitter personal vendetta, V fights passionately for dignity and freedom in a dystopian and fascist Britain.This takes cunning and guile, a certain fearlessness, bravado, a capacity for extremism and a touch of madness.

“He’s a very complex and ambiguous man,” says Weaving. “He’s been imprisoned and tortured, mentally and physically abused. And that has created this vengeful angel, if you like. He’s an assassin, but also a very cultured and educated man who believes strongly in individual freedom.”

With his entire performance taking place behind the immobile mask, leaving him without the facial expressions or eye contact that are fundamental tools for an actor, Weaving had to find other ways in which to humanize and animate V. “I loved doing mask work at drama school a long time ago,” remarks Weaving, “and making V’s mask work onscreen was a great acting challenge.You need to convey a lot through voice, but there are also small, fluid movements you can use that help give the mask a life it might not otherwise have had. It was also a question of trying to work out what the mask says in different light and with various shadings.”

“From the moment Hugo put the mask on, we knew it would work,” says McTeigue. “He has a theatre background, which is important to the character. He also has a great physicality and a fantastic voice. He was able to make peace with the mask’s claustrophobic restraints and convey emotion through his voice and movement.”

V’s use of the Guy Fawkes mask and persona functions as both practical and symbolic elements of the story. He wears the mask to hide his physical scars, and in obscuring his identity, V becomes more than just a man with a revolutionary idea – he becomes the idea itself.

This underscores V’s belief that a man can be defeated, but ideas can endure and retain their power forever. V’s mask also provides contrast to the metaphorical “masks” worn by his fellow citizens, who have surrendered their individual identities and beliefs in order to assimilate and avoid persecution by the government.

“In the film, V is described as an idea rather than a person,” says Natalie Portman, who stars alongside Weaving as Evey Hammond, the young woman in whom V awakens a latent activism. “One of the reasons he is so invincible is because you can kill a man, but an idea can’t be killed. So V represents truth, resistance and individualism. But his vengeance taints his political idealism.”

Playing opposite an actor wearing a mask throughout the entirety of the film was challenging, but director McTeigue had no concerns with Portman’s ability to engage emotionally with the character despite his fixed disguise. “I knew she would be able to play off the mask and help make it come alive.”

A highly accomplished young actress, Portman’s career already boasts roles in Star Wars: Episode I, II and III, as well as acclaimed performances in such films as Closer, Garden State and Everyone Says I Love You. Having previously worked with Portman as first assistant director on Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, McTeigue had witnessed firsthand her incredible talent and focus. “She’s completely professional, and looks luminous,” compliments the director. “But more than anything, her fearlessness and intelligence were perfect for the role.”

“Evey represents the people V is trying to help,” says Silver. “But while she joins V in his campaign to free the people of England, she doesn’t condone his pursuit of personal vengeance. Natalie is such a subtly expressive actress, we knew she possessed the rare ability to portray this kind of inner conflict.”

Evey is orphaned at a young age after her parents are killed for daring to speak out against the repressive regime gaining a stranglehold on their country. Thrust into activism after the politically-motivated death of their son, in a sense Evey’s parents chose their political ideals over their daughter. “She’s had a very personal experience with political activism – one that resulted in her parents’ death and left her alone – so she’s just trying to live her life under the radar and stay safe,” says Portman. “She lives through her fear.”

Until the night that fate hurls V into Evey’s life. Patrolling the streets after the universal 11pm curfew, undercover Fingermen, the state’s secret police, catch Evey alone in a cobblestone alley, stealthily making her way to a friend’s house. With only pepper spray to defend herself, she falls victim to the ruthlessness of their warped use of judicial discretion. But before the encounter disintegrates into brutality, a mysteriously cloaked man appears, saving Evey’s dignity and her life.

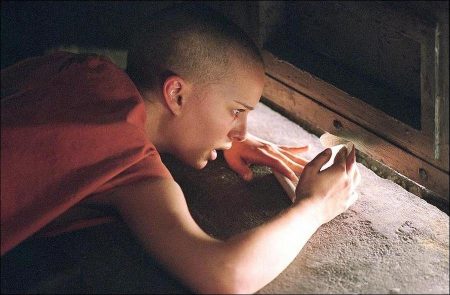

Unknowingly, this chance meeting sparks Evey’s political awakening. In the face of torture and solitary confinement, Evey’s political consciousness becomes fully realized. “Through her imprisonment she learns to face her fear, and overcoming that fear is important for her own integrity,” asserts Portman, who was required to shave her head on camera for a pivotal sequence in the film in which Evey’s identity is violently stripped down by her captors.

Portman was intrigued by the ideas in the story and by Evey’s transformation from an anonymous office worker to a brave and politicized heroine. “The script has really strong political and ideological overtones,” she says. “And it looks at the kind of choices that must be made in order to be a political person, and how those choices affect an individual’s private life.”

In preparing for her role, the actress watched The Weather Underground, a documentary about a group of young American radicals in the late 1960s and 1970s who bombed the Capitol building and broke Timothy Leary out of prison. She also read famed Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin’s autobiography, which describes his early Soviet imprisonment and subsequent leadership of Irgun, a militant Zionist group in Palestine responsible for terrorist activities intent on expelling the British from Palestine.

Portman also found Antonia Fraser’s Faith and Treason about the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 informative. “I learned about the British royal oppression of Catholics and their uprising and the inspiration for Macbeth coming from all the plots on King James I’s life.”

Chief Inspector Finch is the detective on the hunt for V, racing to stop his string of murders and find him before he fulfills his promise to destroy Parliament on the 5th of November. Leading the state’s investigation into the mysterious and eerily similar murders of several prominent figures, Finch is determined at the outset to simply catch the elusive terrorist and his seeming accomplice, Evey.

However, as Finch unearths details of V’s history, he discovers shocking state secrets concealed by the government he serves and his sympathies begin to shift. He starts to question that which he has accepted for far too long. The investigation thrusts reality and truth in his path, waking him from his acceptance of the state’s oppressive stranglehold on the rights and freedoms of its people. Played by actor Stephen Rea, Finch guides the audience through the film’s detective story as he slowly begins to uncover evidence that suggests that the British government may have something unspeakably criminal to hide. “There’s an intriguing element of the hunter becoming very interested in his prey,” says Rea of his character.

Rea feels the ideas in the story are timeless. “It’s about what happens when government pushes people too far. It’s a warning, a pretty ancient warning, about the function of government and its responsibility toward its citizens.

“Andy and Larry are doing interesting and dangerous work,” Rea continues. “It’s a highly ambitious attempt to move something from one medium to another. Graphic novels are obviously static, single frames, and you’re transposing that to a moving picture. It’s tricky and not entirely realistic, but I found that interesting. It was good to be working with something that has a certain heightened quality to it.”

Rupert Graves is Dominic, Finch’s lieutenant and junior partner in the investigation. “He undergoes a bit of an epiphany during the film,” Graves points out. “He’s not a man of great imagination. He’s always put his head down and believed in the state, but he and Finch begin to realize that their government isn’t as good as they had thought.”

The villainous head of England’s totalitarian regime is Chancellor Sutler, played by the venerable John Hurt, two-time Oscar nominee for his lauded performances in Midnight Express and The Elephant Man. Sutler’s government rules by fear, ensuring submission of its citizens through intimidating means – secret police, constant surveillance and the threat of imminent and apocalyptic dangers. Censorship, propaganda, and subverting freedom of speech are the order of the day, and eliminating minorities is but a necessary casualty. “Sutler represents a society that believes that a fascist government is the best way to run a country,” says Hurt. “Don’t ask questions, let the Party get on with it and above all, don’t criticize our authority.”

Hurt starred as Winston Smith in Michael Radford’s film 1984, based on George Orwell’s chilling tale of a totalitarian society ruled by an omnipresent fascist leader. In V For Vendetta, with the exception of a few key moments, Sutler is predominantly seen on an oppressively immense monitor from which he delivers incendiary speeches to the country and erupts in vitriolic confrontations with his cabinet via digital conferencing.

In one comic scene, however, Hurt steps away from the screen to play opposite Stephen Fry in a mock variety show skit in which Fry’s character, television host Gordon Deitrich, daringly – and dangerously – pokes fun at the ruling Chancellor.

Deitrich, a suave television personality hired by the government to produce a daily variety show, is Evey’s trusted friend and confidante. But he has secrets of his own that must remain hidden from the state. “Deitrich must be dragged out of his moral torpor and make a stand,” says Fry of the evolution of his character’s political consciousness. “He rips up the censor-approved script of his nightly show and writes one which makes vicious fun of the Chancellor.”

Most of Fry’s scenes in the film are opposite Portman. “I’m immensely impressed by Natalie,” he says. “I mean, what is she, 12 and a half years old or something? She’s a barely divided embryo and yet she speaks multiple languages, is immensely accomplished and a natural film actress. She’s very bright and good natured. She’s quite something. She’s going to be around at the top of her profession for a long time.”

Rounding out the impressive ensemble cast is Tim Pigott-Smith, who plays Creedy, the head of Britain’s secret police, and V’s final and most dangerous nemesis. While Sutler appears to have the country tightly shackled, the real power rests within Creedy’s grip. Ben Miles is Dascomb, Sutler’s head of propaganda who cleverly spins V’s explosion of Old Bailey on BTN, the government-controlled network, as an “emergency demolition” project.

Two-time Laurence Olivier Theatre Award-winning actor Roger Allam plays Prothero, the arrogant, vitriolic host of a news program called “The Voice of London.” The wildly popular television show attracts millions of viewers who tune in to hear his latest rants, finding solace in the slogan that ends each of his broadcasts: England prevails. “He rants his particular beliefs, serving as a mouthpiece for the government’s propaganda,” says Allam. “His evangelism is a kind of nationalistic fascism.”

John Standing, one of England’s most respected stage, film and television actors, is Bishop Lilliman. This man of the cloth’s religious convictions takes a backseat to his perverse sexual cravings, which ultimately prove to be his undoing. “I thoroughly enjoyed playing Lilliman,” Standing remarks, “because he’s slightly comic and utterly atrocious. Lovely to do.”

The course of V’s life, and subsequently Evey’s as well, has been unalterably impacted by a woman named Valerie Page – a woman who neither of them ever met. Her story is one of the thousands of those who were tortured and killed by the government’s callous cruelty and persecution of those it deemed unfit – and also a story of the small shred of hope that can ignite a revolution. The role of Valerie is played by Natasha Wightman, whose previous work includes Robert Altman’s Gosford Park.

Acclaimed Irish actress Sinead Cusack plays Delia Surridge, a coroner haunted by her horrific past – a past she shares with V. “I never imagined that I’d be playing a vile human being,” says the Tony-nominated actress. “I always thought I was rather soft and sweet and Irish! Instead I’m this vicious killer and for that reason it was a departure for me. This film is really a very interesting psychological study, set in a world that we hope we’ll never have to inhabit.”

About the Production

V For Vendetta is set in London in the near future. Though still anchored by venerable landmarks such as Parliament, Old Bailey and Big Ben, the city, like the rest of the country, has fallen into a state of post-war isolation and depression. Chancellor Adam Sutler wrested incalculable power over this tightly-controlled society by championing his extremist Norsefire party as England’s only safeguard against war, disease and famine.

Yet Sutler’s oppressive policies have stripped the culture of its spirit, vitality and hope. Food is rationed but fear is in great supply. Personal freedoms are an antiquated notion of the past, and no one dare raise a voice in dissent, lest they be “black bagged” by Fingermen – Minister Creedy’s secret police force – and never heard from again. Led by director James McTeigue, the V For Vendetta filmmakers strived to capture the essence of present-day London in their rendering of the film’s grim socio-political landscape.

“England has become quite soulless,” says production designer Owen Paterson, who previously collaborated with McTeigue and the Wachowski Brothers on the Matrix trilogy. “We tried to create a London that is very recognizable, yet frozen by having become this totalitarian state.”

Paterson and costume designer Sammy Sheldon used a palette of gray tones to evoke the bleak, regimented pall that envelops the city and its citizens. “In this environment, choice is limited,” set decorator Peter Walpole notes. “You might be able to buy a car or a can of baked beans, but there’s only one brand available. This was reflected in the television studio set, for example. All of the monitors are the same brand, and all of the desks and chairs are exactly the same.”

The film was largely shot on soundstages and interior settings to underscore the story’s tone of anxiety and alienation. “We wanted to create a sense of claustrophobia, so the film is very purposefully interior,” McTeigue explains.

Filming began in March 2005 at Babelsberg Studios in Potsdam, Germany. With nearby Berlin doubling for a handful of practical locations, the production spent ten weeks on the Babelsberg soundstages before moving to London for a few weeks to shoot principal exterior sequences.

Paterson oversaw the design and construction of a staggering 89 sets for the Babelsberg segment of production alone, including the Jordan television tower, home to the government controlled British Television Network; Victoria Station, a former stop on the ruins of the Underground, which the government shut down years ago; as well as another critical section of the Underground that V has commandeered for use in his plot to blow up Parliament.

On historic Stage 2, where Fritz Lang’s classic futuristic thriller Metropolis was filmed in 1927, the cast and crew of 500 inhabited the grandest and most elaborate of Paterson’s sets: the labyrinthine Shadow Gallery.

Like V himself, his subterranean lair is elegant, mysterious and enthralling – a stylish cross between a crypt and a church, carved from the passageways beneath the city. “I envisioned the Shadow Gallery as an expanded ace of clubs, with a central space and chambers spiralling outwards from the middle,” McTeigue says of the sprawling set, which includes a library, V’s dressing room, a kitchen and a screening room/lounge. “It feels like it’s located beneath some great cultural institution that has long been closed down by the government.”

“The Shadow Gallery is the sort of place that could exist below St. Paul’s Cathedral or Westminster Abbey,” Paterson elaborates. “It’s an arched, Tudor kind of space where you can imagine someone bricked up a door years ago and forgot it was ever there.”

V’s vaulted hideaway also serves as a museum of sorts, a home to his extensive collection of music, film, literature, philosophy and art – all of which has been banned by the government’s Ministry of Objectionable Material. “V has become a caretaker of everything that the government won’t allow,” says McTeigue.

“He’s a guardian of a culture that is in danger of being lost forever,” adds Hugo Weaving. “I suspect there are a number of people in this world who are like him, who have their own hoards, their own treasure troves like the Shadow Gallery.”

One of the biggest challenges for set decorator Peter Walpole and the art department was securing the rights to reproduce the Gallery’s myriad iconic works – and then replicating them and dressing the numerous Gallery chambers. “We had to get an enormous variety of objects – everything from Picassos to Turners, modern art to comic books,” Walpole says.

Walpole’s team also had to collect and arrange hundreds of books to dress V’s makeshift library. It is here that Evey first awakens in the Shadow Gallery and finds herself surrounded by stacks and stacks of treasonous volumes.

“As you enter the room, the books are piled low, as though they’ve been blown in like a bunch of leaves,” Walpole describes. “But as you move toward the far end, the piles grow until they reach the ceiling and line the walls, almost like a snowdrift.”

To give McTeigue and the crew maximum flexibility while filming in the library, many of the books were fastened together like building blocks, so the stacks could be moved quickly and reconnected like Lego components, rather than moved piecemeal.

During production of this scene, Natalie Portman recalls, “James brought in a clipping from a newspaper with a photo of a library that was discvovered in Iraq. The government had shut it down and there were piles and piles of books everywhere. It was sort of incredible, having this real life parallel as we were filming.”

In addition to designing the sets, Paterson also collaborated with McTeigue and art director Stephan Gessler on the creation of V’s eerie mask. More than a mere disguise, an affect of his theatrical personality or a veil for his hideously disfigured face, V’s mask becomes a powerful symbol of the ideas of freedom and expression he represents.

Paterson’s design was modeled on V’s iconic visage from the graphic novel, which illustrator David Lloyd based on the eponymous masks worn in tribute to traitor-turned-folk hero Guy Fawkes. But as drawn by Lloyd, V’s mask takes on different moods and expressions from frame to frame.

McTeigue opted to create a “fixed” façade, rather than using CGI or a flexible mask that could be manipulated to form expressions. “I wanted the face, even though it’s very distinct, to have a ‘universality’ to it,” he says. “I knew that if we achieved the right look for the mask, we would be able to tonally and atmospherically change the way it appears on camera through the lighting design and Hugo’s performance.”

The result, which the director describes as “a cross between a traditional Guy Fawkes mask and a Harlequin mask,” was sculpted from clay – a considerably more imperfect and painstaking process than the modern mold-making method of computer cyber-scanning – then cast in fiberglass and painted with an airbrush to create a porcelain doll-like quality.

“We had a very fine sculptor named Berndt Wenzel who patiently went through seven generations of carving the mask from clay to get the right personality,” Paterson says. “We needed to capture the perfect generic look so that when we lit the mask in different ways, it would take on different expressions.”

Bringing the mask to life was “definitely a collaborative effort,” Weaving reports. Though aided by lighting and cinematography, the actor needed to convey a great deal of emotion solely through his voice and body language, as no part of his eyes, mouth or face are visible behind V’s façade. “James often gave me notes about my dialogue or my performance as I would do it if I weren’t wearing a mask. That was great, because central to making the mask work was making the character behind the mask work.”

Finding V’s voice was crucial to the process. “I knew I didn’t have to worry about my voice being muffled by the mask when we were filming, because we would re-record my dialogue in postproduction,” says the actor. “But it’s still important to find the character within the voice and give the right performance on the day.”

In addition to the challenges of emoting through the mask was the considerable challenge of learning to work with the mask. “It has a very narrow field of vision,” McTeigue explains. “Hugo’s actual eye-line when he’s looking at the character he’s playing opposite is at their stomach.”

Weaving also had to integrate acting in the mask with the character’s wig, hat and a heavy cloaked costume featuring a high neckline that restricted his head movement. “The amount of sweat that pours off you when you’re wearing a wig, a hat, a very hot costume and a mask is phenomenal,” Weaving says good-naturedly.

Created by costume designer Sammy Sheldon (Black Hawk Down, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy), Weaving’s wardrobe was styled after McTeigue’s vision of V as “a cross between the actual Guy Fawkes character and a gunslinger.”

“V’s costume is rooted in the 16th century, but we chiseled it down to look more simple, sleek and modern – futuristic in an historical way,” says Sheldon, who crafted the ensemble from cashmere, wool, leather and an original 16th century silk basket weave. “V’s hat was modified, for example. We shortened it and made it cleaner, instead of fancy and feathered as it would have been in Fawkes’ time.”

As with V’s wardrobe, his weapons of choice – six handmade throwing knives – reflect a combination of period and modern design. “When V opens his cloak, I wanted it to look as though he has metal teeth attached,” McTeigue explains. “Our armorer, Simon Atherton, did an amazing job of crafting V’s knives and creating the metal sheaths they slide into.”

V’s chillingly exquisite calling cards, Scarlet Carson roses, were portrayed in the film by red Grand Prix roses. The prop department purchased dozens of Grand Prixes daily to ensure there were always a few on hand at the studio in the perfect state of bloom for filming.

While Weaving contended with his character’s multi-faceted costume, Natalie Portman had a much more minimalist wardrobe challenge in portraying V’s unlikely accomplice, Evey Hammond: she was required to have her head shaved on camera for a pivotal sequence in which Evey is imprisoned and tortured to reveal V’s identity.

Knowing he had only one take to capture Evey’s anguish as Portman’s auburn locks were stripped, McTeigue used multiple cameras to cover the action and asked the film’s hair stylist, Jeremy Woodhead, to handle the shears.

Portman found the experience liberating. “It’s been really nice to step away from vanity a little bit,” she says. “The time you spend on your appearance as a woman – if you put all that together you’d have an extra ten years of your life. It’s been great to get away from that. But at the same time, it takes a really long time to grow back, so the sooner, the better!”

Another powerful shot that McTeigue and company needed to achieve in one take is a stunning sequence in which V touches off thousands of dominoes meticulously arranged in an intricate “V” pattern on the Shadow Gallery floor.

Four professional domino assemblers from Weijers Domino Productions spent 200 hours of building time placing 22,000 dominoes in position for the breathtaking visual feat. During the setup, the stage had to be closed to everyone but the assemblers, as a slight disruption flattened the dominoes at one point early on.

Tension was palpable on the set the day the scene was filmed, lest anyone’s footsteps or voice tumble the dominos again. Loud gasps were heard when an assistant hairstylist dropped her comb while grooming V’s locks as he sat cross-legged at the head of the domino chain. Fortunately, the comb narrowly missed the first piece. The dominoes were then officially “touched off” – and fell into place perfectly.

In addition to months of soundstage work at Babelsberg, a few weeks of location filming were completed in Berlin. A flashback of Chancellor Sutler’s Norsefire rally was staged in Gendarmen Market; scenes in Bishop Lilliman’s bedroom chamber were filmed in a rambling castle in Potsdam; and a former chicken farm was transformed into the sinister Larkhill detention facility.

It was at the Larkhill location that stunt coordinator Chad Stahelski, a four-year veteran of the Matrix trilogy as martial arts stunt coordinator and Keanu Reeves’ stunt double, walked through searing flames to achieve a haunting shot emblematic of V’s harrowing past and his indomitable quest for vengeance.

While principal photography rolled on at Babelsberg, an advance team prepared for the final few weeks of filming in London. Owen Paterson’s art department transformed exterior locations to convey the dull pallor of the strictly-controlled society – removing advertising signage, all signs of public transportation and any splashes of color or brightness.

“We wanted everything to be gray,” says set decorator Peter Walpole. “Then we added surveillance cameras and telegraph poles with speakers mounted on them to emphasize the ‘Big Brother’ atmosphere.”

For flashbacks to the 1990s that depict life in England prior to the election of ultraconservative Chancellor Adam Sutler, the sets are “a little more cluttered, a little more lived in, a little freer,” Walpole describes. “In the scenes set in the present day in the film, there’s not quite as much set dressing. Everything’s a bit more regimented. There’s a subtle contrast.”

The film’s climactic sequence, set in the shadows of Parliament, took place on Whitehall, the iconic thoroughfare running from Nelson’s Column at Trafalgar Square to the Parliament Buildings and Big Ben.

Home to such high-profile Westminster addresses as 10 Downing Street and the Ministry of Defense, the security-sensitive thoroughfare had never before been closed to traffic to accommodate filming. After nine months of negotiating with 14 government departments and agencies, including the Ministry of Defense, location supervisor Nick Daubeney secured unprecedented permission to close the street for filming between the hours of midnight and 5am for three consecutive nights. This gave the production only four hours of shooting time per night, given the setup and removal of equipment, personnel and the production’s vehicles, including two army tanks.

As with the multiple permissions secured to film on Whitehall, the production also had to obtain authorization for the use of the two tanks and simulated weaponry during rehearsals and filming at the location.

The decommissioned ex-military tanks were acquired from a prop warehouse in the UK. Prior to transporting the vehicles to Whitehall for filming each night, the tanks were inspected offsite by government security personnel to ensure their weaponry was not functional nor had been altered in any way. They were then taken via trucks to the location – with no stops or changes to the tanks allowed during transport – and were accompanied by security officials at all times. (On screen and on set, the tanks moved under their own power.)

Background checks were conducted on every actor and technician who carried simulated weapons during production of the Whitehall sequence. Barcodes on the weaponry were scanned to track each piece and the individuals authorized to handle them. Meanwhile, government security personnel surrounded the production at all times – some of whom were identifiable to the cast and crew, and others who maintained anonymity within the crowd to ensure the security of everyone involved.

This ambitious sequence also required costume designer Sammy Sheldon and her team to outfit 500 extras in replica V cloaks and hats, as well as fabricate uniforms, helmets and flak jackets for 400 extras portraying militia.

Following the completion of principal photography, visual effects supervisor Dan Glass and the V for Vendetta miniatures unit, led by Model Unit Supervisor José Granell, spent ten days detonating large-scale models of the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben and Old Bailey for key scenes in the film.

While some computer-generated effects were later fused with footage of the models being exploded, it was important to the filmmakers that the explosions, which carry great symbolic value, be as realistic as possible, so they opted for the practical effect of detonating physical replicas of the buildings over CGI.

“The models provide a real, tangible environment,” Granell explains, “and when you’re dealing with physical elements such as water and fire, and especially pyrotechnics, you get a better look when you have real, physical events taking place. With CGI, unless you actually deliberately create them, you don’t get any accidents – so you don’t get that essential feeling of nature doing its own thing.”

The filmmakers chose to utilize large-scale models in order to create a realistic relationship between the size of the buildings and the pyrotechnic events being filmed. Built in eleven weeks at Shepperton Studios by the London firm Cinesite, the plaster models were constructed at one seventh scale, which yielded an impressive 20-foot replica of Old Bailey, with the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben towering at approximately 30 feet high and the length of Parliament stretching 42 feet long.

During the course of their research, Granell and his team studied documentary footage of actual stone buildings being exploded to get a feeling for how stone reacts to detonation. From there they began their experiments with materials. Since plaster breaks up well and behaves most like stone when detonated, the models were predominantly constructed with cast plaster. The team experimented with a variety of plaster recipes for different areas of the model – some components had to be more rigid, while some of the finer detail necessitated a weaker version of the plaster.

Prior to the final filming, an effects element shoot was held during which the team performed individual pyrotechnic explosions that they would later be able to use in post-production. They tested a variety of combinations of types of charges and different varieties of plaster, to see how each pairing performed on film. “For instance, one of the problems we found is that the weakened plaster we used tended to create too much dust,” says Granell. “And the one thing I didn’t want to do was hide any of the color of the actual combustible elements – the pyrotechnic charges, the flames, all of those details. So we adjusted the plaster recipe to remedy the problem.”

The team had to study the architecture of the Old Bailey and Parliament buildings inside and out, in order to accurately surmise how the structures would react to the detonations. For instance, how fast the explosions would travel through the building, how the structures would break apart – which areas would give first, which would be able to withstand the blast, what the size of the fragments would be and how fast and far they would travel.

In addition to this structural accuracy, the designers studied the outer detail of the legendary buildings to achieve exactly the right look. “You’ve got to be a real stickler for detail,” says Granell, “and pay close attention to how the real building looks – such as design elements or the aging of the stone – so that you can match it. You have to keep in mind that you’re dealing with structures that are potentially very familiar to a lot of people, who will be in a position to judge whether they look right or not.”

All of the research, time and work put into creating the incredible structures resulted in extremely convincing detailed models and detonations that look authentic onscreen and performed perfectly during filming. “The buildings looked just fantastic,” says Granell. “I apologized in advance to the chaps who were working for us because they put a lot of hours into this and the miniatures looked beautiful – until we blew them up. So the only thing I could do was make sure we did a good job of blowing it up, and make it all worthwhile!”

V For Vendetta will be released in IMAX® theatres worldwide, in addition to conventional theatres, beginning March 17, 2006. The film has been digitally re-mastered into the unparalleled image and sound quality of The IMAX Experience® with proprietary IMAX DMR® (Digital Remastering) technology. V For Vendetta represents the fifth IMAX DMR film commitment from Warner Bros. Pictures in 2006, and the 13th DMR collaboration between IMAX and Warner Bros. since 2002. IMAX Theatres deliver images of unsurpassed clarity and impact, and will enable audiences to experience the thrill and intensity of V For Vendetta on the world’s largest screens, surrounded by state-of-the-art digital sound. (IMAX screens can be three times larger than the average 35mm screen, 4,500 times larger than the average TV screen, and as wide as an NFL football field.) “We’re excited to give fans the opportunity to experience V For Vendetta in IMAX’s spectacular format,” said Joel Silver, producer of V For Vendetta. “The clarity and immersive quality of The IMAX Experience adds a dynamic dimension to the film’s powerful visuals, breathtaking action and multi-layered storytelling.” The sheer size of a 15/70 film frame, combined with the unique IMAX projection technology, is key to the extraordinary sharpness and clarity of the images projected in IMAX theatres. The 15/70 film frame is ten times larger than a conventional 35mm frame and three times bigger than a standard 70mm frame. IMAX projectors are the most advanced, powerful and highest-precision projectors in the world, and the key to their superior performance is the proprietary “Rolling Loop” film movement. The Rolling Loop advances the film horizontally in a smooth, wave-like motion. During projection, each frame is positioned on fixed registration pins, and the film is held firmly against the rear element of the lens by a vacuum. As a result, the picture and focus steadiness are far above normal projection standards and provide outstanding image clarity. To fully envelop IMAX theatre-goers, the IMAX sound system is a specially designed multichannel stereo system that delivers superb clarity and quality for maximum impact. The IMAX Proportional Point Source loudspeaker system was specifically designed for IMAX Theatres and delivers superb sound quality to every member of the audience, regardless of where they may be seated. Directed by: James McTeigue Visits: 133V for Vendetta (2006)

Starring: Natalie Portman, Hugo Weaving, Stephen Fry, Rupert Graves, Stephen Rea, Tim Pigott-Smith, Roger Allam, Natasha Wightman, John Standing, Emma Field-Rayner

Screenplay by: Andy Wachowski, Larry Wachowski, Alan Moore

Production Design by: Owen Paterson

Cinematography by: Adrian Biddle

Film Editing by: Martin Walsh

Costume Design by: Sammy Sheldon

Set Decoration by: Peter Walpole

Art Direction by: Marco Bittner Rosser, Stephen Bream, Stephan O. Gessler, Sarah Horton, Sebastian T. Krawinkel, Kevin Phipps

Music by: Dario Marianelli

MPAA Rating: R for strong violence and some language.

Distributed by: Warner Bros. Pictures

Release Date: March 17, 2006