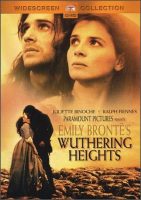

Taglines: A passion. An obsession. A love that destroyed everyone it touched.

Wuthering Heights movie storyline. Peter Kosminksy directed this faithful adaptation of the Emily Bronte classic. Ralph Fiennes has the role of Heathcliff, a wanderer adopted by the father of Cathy (Juliette Binoche), “a wild slip of a girl.” Heathcliffe is looked down upon by his stepbrothers and becomes a servant. He is further crushed when Cathy, the love of his life, marries another man — since to marry a servant would be the ultimate in humiliation for her. Heathcliffe disappears for a number a years but then returns, revenge and hatred for Cathy’s family the only thing on his mind.

Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights is a 1992 feature film adaptation of Emily Brontë’s novel Wuthering Heights directed by Peter Kosminsky. Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, released in 1992, is based on the 1847 book by Emily Brontë which was written a year before her death. This particular film is notable for including the oft-omitted second generation story of the children of Cathy, Hindley and Heathcliff.

The film stars Ralph Fiennes as the tortured Heathcliff and Juliette Binoche as the free-spirited Catherine Earnshaw, in a precursor to their later, successful collaboration on The English Patient. The role of Heathcliff opened up doors for Ralph Fiennes to play Amon Goeth in Schindler’s List. American director Steven Spielberg claimed he liked Fiennes for Goeth because of his “dark sexuality.”

Film Review for Wuthering Heights

n the version of Cole Porter’s “Let’s Do It” that he used in his Las Vegas nightclub act in the 1950s, Noël Coward included a celebrated couplet that threw doubts on the much vaunted sexual prowess of America’s most macho author while extolling the adventurousness of a 19th-century English country vicar’s three daughters.

“The Brontës felt that they must do it, Ernest Hemingway could just do it,” he sang, and indeed the range of social, psychological and sexual experience Emily, Charlotte and Anne explored in their novels is remarkable. So much so that only one of the several film versions of Emily’s Wuthering Heights made over the past 90 years has attempted to encompass the book’s 30-odd years of pain, misery and ecstasy and its three generations of man handing on misery to man in the west Yorkshire countryside.

The most famous film, the characteristically polished William Wyler-Sam Goldwyn production of 1939, covers just the novel’s first half and was co-scripted by Ben Hecht. One of the five Hollywood movies Hecht worked on that year (the others were Gone With the Wind, Gunga Din, Let Freedom Ring and It’s a Wonderful World), it concentrated on the passionate, doomed romance between Laurence Olivier’s Byronic Heathcliff and Merle Oberon’s stunningly exotic Cathy Earnshaw.

It does, however, begin with Lockwood, the wealthy new tenant of the elegant Thrushcross Grange, visiting and being bowled over by his mysterious neighbour up the hill at the windswept Wuthering Heights, and it also uses the housekeeper Nelly Dean (Flora Robson) as what we would now call the tale’s unreliable narrator.

The only film to draw on the whole book, bringing in the part that might be described as “Heathcliff’s Revenge”, is the documentarist Peter Kosminsky’s otherwise uninteresting 1992 British version. The film announced itself as Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and had Sinead O’Connor as Emily returning to the deserted Wuthering Heights to invent her tale and caution the audience “not to smile at any part of it”.

Andrea Arnold, the British realist who directed this new Wuthering Heights, won major prizes at Cannes for her first two feature films, Red Road and Fish Tank, both resolutely set on run-down housing estates in present-day Britain – Glasgow in the first case, the eastern fringe of London in the second. They showed little indication of an interest in or aptitude for making a period movie in a late-18th-century rural setting.

In retrospect, however, one can see in the dangerously charming anti-hero played by Michael Fassbender in Fish Tank a likely Heathcliff. When he shows a teenage girl how to catch fish by hand, there are reminders of the idyllic scenes in Ken Loach’s Kes where the lonely boy finds transcendence in training his predatory bird in the Yorkshire countryside.

Following Ben Hecht’s example, Arnold and her co-writer, Olivia Hetreed, have dropped the book’s second half, but they have also jettisoned Lockwood as the initial narrator and greatly reduced the significance of Nelly Dean. The movie begins with the surly Christian gentleman-farmer Mr Earnshaw returning to his spartan home on the Yorkshire moors at Wuthering Heights with a teenager (Solomon Glave) he’s found wandering the streets of Liverpool.

Described in the novel as black-eyed with a dark complexion and possibly of gypsy stock, he is immediately identified in the film as black, and scorned as a “nigger”. This feral child becomes a disruptive part of the Earnshaw ménage and is baptised Heathcliff, a name appropriately suggesting an abyss at the edge of a forbidding open space. Told nothing of his background, we’re left to infer that he’s a fugitive slave, and we inevitably think of Samuel Johnson’s devoted servant Francis Barber. But the movie does little to explore his character other than seeing him as a perpetual outsider, although we seem to be looking at the world through his eyes.

We’re made to understand the sense of wonder Heathcliff feels in the awesome countryside. We sense the rapport he has with Earnshaw’s teenage daughter Cathy (Shannon Beer). We sympathise with the resentment engendered by the cruel treatment meted out by Cathy’s weak, vindictive brother and the Caliban-like desire for revenge that grows over the years of subservient humiliation.

The movie is at its strongest in these early scenes as Cathy and Heathcliff form a childhood bond against the bitter world and become one with each other in the natural world, suggestive of the friendship that young slaves briefly forged with their masters’ children in the deep south. This is helped by the excellent naturalistic handheld camerawork of Arnold’s regular cameraman, Robbie Ryan, and a remarkable soundtrack designed by Nicolas Becker that incorporates wind, birdsong, barking dogs, rain, the flapping of shutters, the whispering of leaves, the chattering of insects and the creaking of trees into a great symphony of nature.

The movie takes an uneasy turn when Cathy is absorbed into the civilising world of Thrushcross Grange, and Heathcliff is quite literally thrown out, as well he might be after telling the genteel Lintons: “Fuck you. You’re all cunts.” Shortly thereafter he leaves to make his mysterious fortune and be transformed into a gentleman, only to find on his return that Cathy has married Edgar Linton.

With both roles now taken by older actors (James Howson as Heathcliff, Kaya Scodelario as Cathy), the movie never recovers its early power and at times becomes confused, ponderous, and risible. The novel and the 1939 film introduce Heathcliff as a fascinating, insoluble enigma. In Arnold’s movie he’s merely a puzzle, a tornado of resentment whirling destructively across the bleak and intimidating landscape. But the film is by no means negligible.

Wuthering Heights (1992)

Directed by: Peter Kosminsky

Starring: Juliette Binoche, Ralph Fiennes, Janet McTeer, Sophie Ward, Simon Shepherd, Jeremy Northam, Jason Riddington, Simon Ward, Janine Wood, Jennifer Daniel

Screenplay by: Anne Devlin

Production Design by: Brian Morris

Cinematography by: Mike Southon

Film Editing by: Tony Lawson

Costume Design by: James Acheson

Set Decoration by: Caroline Cobbold

Art Direction by: Richard Earl

Music by: Ryuichi Sakamoto

MPAA Rating: PG for theme, language and elements of violence and sensuality.

Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: October 16, 1992

Hits: 266