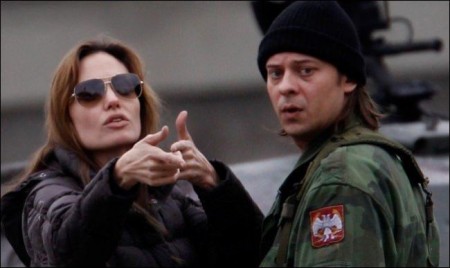

As a first-time director, Angelina Jolie wanted great talent on the crew who could create a comfortable working environment. “I wanted good people around this cast and this subject matter,” she says. “I wanted people with heart who wanted to do this for the right reasons.”

The first step was to find the producer who would nurture the project as closely as she would, and for Jolie, that was Graham King. “I don’t think anybody else would’ve done it beside Graham,” she says. “It’s a famously unpopular subject matter, especially with film. Financially, it’s not been a lucrative subject matter for producers. I chose Graham because I’d worked with him before. He’s a very direct, no-nonsense person and I knew he’d just tell it to me straight. We would go head-to-head. If we had to fight something out, we’d come to a conclusion together. There wouldn’t be 30 executives to please.”

One of the first crew members she approached was her DP, Dean Semler. Australian by birth, Semler has built an impressive résumé in Hollywood, winning an Academy Award® in 1991 for lensing Dances with Wolves. Jolie worked with Semler on The Bone Collector, and the two had remained close. “I wrote to him, asking if he’d read the script and if he would recommend people I could call for this,” Jolie recalls. “I assumed he’d just give me a list of names that would be good for the film. But then he said, ‘I’ll do it.’ I couldn’t believe it.”

Semler was excited to be a part of such an intimate project. “I’ve shot a lot of big Hollywood pictures,” he says. “To read a script that was totally on the other end of the spectrum was just wonderful. I fell in love with the script when I first read it.”

Getting the look right was of paramount importance—a way of maintaining authenticity. “Angie showed me a lot of photographs as references,” Semler recalls. “It was very inspiring to see how she wanted the film to look. She knows what she wants and will tell me exactly how she wants it to look.” Jolie knew that Semler’s highly versatile talent would be able to pull off the right balancing act between beauty and destruction.

“He’s so talented that you could look at a few of his films and none would look quite like the other,” she says. “Dean has such a confidence and ease. I knew that he would make it beautiful without making it so beautiful that it became poetic and not real. I knew that he would capture something that would have elegance to it, but not so overdone that you would become distracted by the photography. It had to have beauty in it, though.

We talked a lot about the fact that there was no electricity during the war. We had to work a lot with a single bulb, or windows—single light sources. We drew on Vermeer and Rembrandt, anything that we could think of that would bring us around to the challenges of lack of light. It’s not a very expensive film, but the way he shot the film makes it look like it cost much more than it did.”

Jolie had recently worked with production designer Jon Hutman on The Tourist, a film that had a very different approach to set design. But she knew that their working relationship would be right for In the Land of Blood and Honey. “He’d never done a war film,” Jolie says, “and suddenly he was in rubble. We’d just come off The Tourist where everything was beautiful, and here he is in mud! He was so great to work with.” Hutman loved the collaborative nature of the production process. “The best collaborations I’ve had with directors are those who come with the movie in their heads. Angelina came to the set with what she wanted, but she was always open to suggestions and ideas, while keeping the ship on course.”

Costume designer Gabriele Binder brought a keen eye toward the authenticity of the period and of the location, something that Jolie greatly appreciated. “I think one of the most misunderstood things about filmmaking is costuming,” Jolie says. “People often get acknowledged for great wardrobe for a period piece or some extreme drama, something that really stands out to the eye. But I think the hardest thing to do, hands down, is to make something look real.”

Binder agrees. “We tried to come close to the people who lived through the war, to their reality,” she says. “She understood the colors of that time, of 1990s Yugoslavia,” Jolie says. “We picked colors for each character that are so subtle you might not even notice.” “I knew lots of people in the areas of Bosnia that were excited to send me materials so that I could understand their clothes better,” says Binder. “We had an idea about what we liked with color. We tried to stay with blues and browns—something very Eastern European. It’s not necessarily immediately beautiful, but as you look at it, you are drawn to it.”

“Hopefully, they will feel like real people’s clothes, matched to real personalities,” says Jolie. To do that, Binder spent a great deal of time with each individual actor in order to create unique costumes for their characters. “Gabriele talked to each actor in such detail that every single one of them, no matter how small their part, had a real say in who they were, and why they were dressed the way they were. That’s very, very hard. In military uniforms, for example, everyone is wearing the same clothes, and sometimes they can look like they don’t suit the person wearing them – they can be too shiny, too new. . Gabriele managed to get past all of those hurdles. I think she’s extraordinary.”

Semler, Hutman, and Binder have all marveled at Jolie’s collaborative nature. But for her, that instinct seems perfectly natural. “I walked on that set every day so grateful and amazed that I was surrounded by so many talented, extraordinary people. It would’ve been foolish to not let them help guide the process,” she relates.

“I think that’s the most wonderful thing about filmmaking: the team. I never felt that as much as an actor because we’re separated from the crew. Emotionally, we’re in a place that we have to stay in. We live in that second world, the world inside the production. The crew works as a team, as a collaborative unit. You inspire each other; you get excited by each other’s ideas. It’s the most fun part of the creative process. It’s wonderful to be a creative person, but to play, experiment and learn with others is really what we all want. I couldn’t imagine it any other way. Every single person who worked on that film taught me so much.”

Jolie wanted to make everyone feel as close and as familial as she could, and recognized that the different emotions involved with each character’s relationships would require different approaches. “Rade and Goran tended to rehearse,” she recalls. “They wanted to rehearse. They had met and discussed it, and it was their way. That was fine with me.

I felt that as they spent time together, and the more they got to know each other, play together, the more familiar they would be. It wasn’t extensive, but it was the method.” Kostiã felt that familial kinship as soon as he and Ðerbedþija began working together. “He’s such a huge actor with this enormous body of work. I felt this father-son relationship immediately when I met Rade. I felt this great respect for him. We would spend an hour rehearsing before we would shoot a scene. I’ve worked with a lot of actors of that generation, and they never rehearse. Rade’s different.”

“With Zana and Goran, however, we didn’t rehearse,” says Jolie. “We wanted them to surprise each other. So often, one of them would have information the other one didn’t have. They could have the ability to be really looking at each other for information. We wanted that chess game to always exist between them. I never encouraged them to be too comfortable with each other. You wanted them to keep a bit of distance so that they weren’t sure.” Kostiã felt similarly. “I don’t really want to know what Ajla is thinking or feeling when Danijel is not there,” he says. “It gave our relationship a dynamic. I knew what Ajla was saying to Danijel, but beyond that…The more we got into it, the more strongly we felt this trust as actors. We were trusted.”

That trust was felt strongly by Marjanoviã as well. “The three of us—me, Goran, Angelina—worked as a team. From day one, it felt like we knew each other for a long time, that we were really good friends. As with any film, you have to feel the trust from your partner. This trust between us was never broken. Once you have that, everything can run smoothly.”

An important example for Jolie became the scene where Danijel discovers that Ajla has been raped. “In that scene, I knew that as an actor, if I was forced to do that in pieces and for too long, it would drain me and I would start to be conscious of my behavior; it would be very painful and not as organic. We made sure that everything was ready on that day, that the cameras and lights were set, so that Goran and Zana were able to do it all in one go.

There’s a cut in the edit, but we did shoot it all in one take. I came in and told them, ‘We’re gonna do this hopefully two times, and hopefully that will be it. I know that it’s cold, and it will be very difficult, but if you can get into it, feel it, and give me everything you’ve got, I will not make you do this 30 times. It’ll be our job to come to you, to move around you, to sculpt it with the camera and the editing. But right now, give me everything you’ve got.’ We pushed through that morning, and it was a very physically and emotionally challenging morning for both of them. But then it was done.”

Location shooting occurred in Budapest, Hungary. “We wanted to shoot in Sarajevo, but the city doesn’t look like it did then,” says Jolie. “None of Bosnia really does, with the exception of a few pockmarked buildings, because—fortunately—it’s physically recovered. Budapest had a lot of empty space to shoot, and the architecture and landscape looked very similar. At the time we shot our film, they opened a studio. It was a great place to shoot. But it was important to include shots that were genuinely of the area. There were a few days shot in Bosnia, like in the opening of the film—a lot of wide shots and plate shots. We needed to bring in the beauty of the country, the real landscape.”

Jolie sought out composer Gabriel Yared to work on the score. Yared won an Academy Award in 1997 for scoring The English Patient. “I’ve always loved Gabriel’s music on different scores in the past,” she says. “He brings in music that’s organic to the region where the film is set. He’s a very classical composer, and I felt that the film should have that sense. He’s clearly one of the most talented composers around. He also has a great depth of emotion. I find his music very moving.”

Yared’s method is rather unusual in the world of film scoring. “His process is to come in very early,” says Jolie. “He came on set and stepped into the rooms where the music took place. He sat with the actors, and understood their feelings. He spent private time with them, talking about their characters and their lives. He then went away and thought about the piece as a whole. And then he slowly started to send me things as I cut. When I received “When the Heart Dies,” the final song one day, it arrived in the editing room. He said, ‘Go sit by yourself and play it loudly.’ I went to my car and was blown away. It was perfect. I admitted to him that I cried!”

Jolie’s relationship with editor Patricia Rommel was incredibly close. “Patricia is such a wonderful, extraordinary editor. She’s the perfect person to work with. She has great taste and an amazing amount of patience. We worked very tightly together. I didn’t leave. We stayed side by side throughout the process.” When the first rough cut was completed in English, everyone was a bit surprised. “Our first cut of all the material was 4 ½ hours. Apparently, that’s not good news. We had a 95-page script, no money and 4 ½ hour first assembly. I could not figure out how that happened but after months in the editing room, Patricia and I managed to cut it down to a shorter running time of 2 hours.” Healing Wounds

One could argue that the very existence of In the Land of Blood and Honey—a film in which Serbian, Bosnian Serb, Bosnian Muslim, and Croatian Serb actors all worked together in a spirit of community and familial spirit—offers a rejoinder to what the war represented, namely ethno-religious division and strife. Creating that sense of harmony worried Jolie at the outset, but after the first day of shooting, she witnessed a powerful and heartening moment. “The very first scene we shot was one of the heaviest in the film. It’s the scene when the women are taken off the bus and brought into the school. That was our first scene! I woke up that morning terrified, but you have to tell yourself to get past that fear.

“It was a lot on the first day. That scene remains one of the most emotional moments in the film. It was the first time that these actors had come together in a scene. The men are pulling the women off the bus. Nobody knew each other. The male soldiers were mostly played by Serbians and Bosnian Serbs, and the main women were all played by Bosnians. The women didn’t know the men who were ripping their jewelry and coats off of them. Then we went into the rape scene. It was so emotionally heavy that it was going to do one of two things: It would either put us in a really bad place, or it would pull everyone together to focus on what this film was about. It would pull us into a certain reality.

Everyone was going to bond, because if we can make it through this day, we can make it through anything. But after lunchtime, I saw two women hugging each other. When I called ‘cut’ the first time, the man playing the soldier who rapes the woman, hugged the actress playing the victim to make sure she was OK. All of the guys who had ripped the coats and jewelry off the women then immediately picked the coats and jewelry off of the ground and re-dressed the women themselves. Wardrobe didn’t do it—they did it. That was the beginning. That morning, looking at what had to be done and what had to be asked of people who were on opposite sides of this conflict, to ask them to come together and do this together—it was incredible.”

The making of In the Land of Blood and Honey suggests that healing is possible, and that it’s necessary to remind the world of the dangers of ethnocentric and nationalistic ideology. Kostiã hopes the film will be a force for good. “I hope that this will be one of those strong pillars of understanding of what happened then,” Kostiã says. “These stories have to be re-told again and again. A younger generation doesn’t know what happened. If we do not revisit these events, things won’t change.

These events get forgotten, accepted. It’s important for these stories to be re-told every three, five, or seven years, and in the harshest ways possible. We must remind the younger generations about things that have gone on before. This way, when we say, ‘Never again,’ we know what ‘never again’ really means. If one person is able to forgive because of this film, or if 10 kids in the future understand something in a positive way about this period of our history, then that is truly a success.”

For Angelina Jolie, the success of the film belongs to those who helped make it, those who lived through and survived this terrible event. “It’s less about what I accomplished, and more about what the cast accomplished by making this project together. That message of unity and desire for a peaceful future the cast sends is what will make the biggest difference.”

Visits: 70