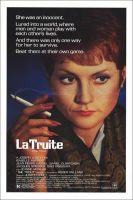

The Trout movie storyline. Frederique (Isabelle Huppert) leaves her family’s small-town trout farm to embark on an journey taking her to Japan and into the arms of a man. Irritations concerning her actions and present state of feelings begin to fill her mind, forcing her to come to terms with innermost self.

The Trout (French: La Truite) is a 1982 French drama film directed by Joseph Losey based on the novel by Roger Vailland and starring Isabelle Huppert, Jacques Spiesser, Jeanne Moreau, Daniel Olbrychski, Jacques Spiesser, Jean-Paul Roussillon and Lisette Malidor.

Joseph Losey’s best film in a decade, is a plum pudding for auteurists. Sexual ambivalence, elaborate settings and camera work, game-playing, the corruption of the bourgeoisie, the intrusion of an outsider upon a social body, you name it—there are the Loseyan leitmotifs in abundance. More important, The Trout was the most enjoyable film on view at Lincoln Center this year.

In the Roger Vailland novel on which the film is based, all but one of the principal characters are introduced in the first chapter, which takes place in a bowling alley. That is where they are to be found in the first scene of the film: Frédérique (Isabelle Huppert), a peasant girl from a trout farm; Galuchat (Jacques Spiesser), her homosexual husband; Rambert (Jean-Pierre Cassel), a businessman who works for a multinational company; Rambert’s associate, Saint Genis (Daniel Olbrychski); Rambert’s wife, Lou (Jeanne Moreau).

Frédérique hustles the bourgeois bunch in a bowling match, then spends the rest of the film bowling the men over, beating them at their own sex, money, and power games, penetrating their world without ever being penetrated by it or them, and unleashing passions in others without manifesting the slightest emotion herself. In a sense, this virgin is a whore, a Loulou who will not put out. Her character is a near inversion of the angel-messenger figure played by Terence Stamp in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema.

Before production started, Gaumont requested Losey to drop the bowling sequence from the script. Fortunately, he stuck to his guns. The scene is thrilling, a remarkable technical tour de force: long takes, great traveling shots on a Louma crane establishing the bowling alley as a sexual metaphor. (Anyone for a game of Losey? Cricket: The Go-Between; hide-and-seek; The Servant; rugby: Accident; pig-grabbing match: The Gypsy and the Gentleman.)

Saint Genis invites Frédérique to accompany him on a business trip to Japan, where her picarescapades flesh out the film’s finest sustained sequences. And as she rises socially, her hair gets shorter; during a scene of Huppert being cropped while watching sumu wrestling on TV, I flashed back to the director’s first film, The Boy with Green Hair (1948), in which a haircut was also a dramatic plot element.

Losey is not above a bit of self-referential sport. Alexis Smith’s show-stopping scene as an American matron cruising her way through Tokyo (she catalogues to Huppert the cities of the world in which she has made love) is a reprise of Leporello’s Catologo aria in Don Giovanni, in which he delineates the geography of his master’s sexual conquests. The presence of Ruggero Raimondi (Losey’s Giovanni) in the cast of The Trout confirms that this is no Accident.

The superb cinematography is by Henri Alekan, who worked with G.W. Pabst and Marcel Carné and who lit Jean Cocteau’s La Belle et La Bête. The memorable “Japanese” interiors are all sets built in French studios to the designs of Alexandre Trauner (Children of Paradise); the entire film is an architectural stunner.

Vailland (1907-1965) from Savoyard peasant stock, became a Resistance fighter during the Occupation and specialized in train derailments. In post-war France, he seemed a strange literary figure: although a Communist, he was a self-proclaimed libertine, with a taste for Sade and Choderlos de Laclos, and thus markedly at odds with the notorious puritanism of the Party to which he belonged. His Goncourt Prize novel, La Loi, was made into a film by Jules Dassin in 1958. In 1959, he wrote the script for Roger Vadim’s modernized version of Laclos’ Les Liaisons Dangeureuses. (There is more than a whiff of Laclos in La Truite, both book and film.)

La Truite was written as Vailland was dying of cancer. Shortly after the book’s appearance, Losey planned a movie version which was to star Brigitte Bardot, Charles Boyer, Dirk Bogarde, and Simone Signoret. He could not find backing at that time. The cast he finally assembled is beyond reproach. Huppert has not done better work with any French director; Olbrychski is dubbed by Jacques Perrin, yet makes a strong impression.

The action in the novel’s opening chapter is similar to that of the first scene in the film, with one important difference. It is narrated in the first person by Vailland, the novelist, who doubles as the character, Roger, a friend of Rambert, Saint Genis, and Lou, and who is present at the bowling alley. Roger is so taken with this encounter of characters from such different milieus that he decides to write a book about it—the book that is being read. Succeeding chapters on Frédérique’s progress in society are narrated to Roger in turn by Rambert, Saint Genis, and Frédérique herself. The style and cast of these chapters are neo-eighteenth-century roman.

The film’s Japanese journey replaces what in the book is Saint Genis’ narration of a business trip he took to the company’s Los Angeles headquarters, accompanied by Frédérique. They make a side trip to an Indian reservation in Colorado—a wildly comic interlude. The film’s Hamada, the company’s Japanese gray eminence, who becomes a father figure for Frédérique, derives from the book’s Mr. Isaac, a Jewish millionaire who meets her in L.A., takes both Galuchats to his bosom, and is last seen conducting them on a tour of the art museums of Europe.

Vailland does not despise Frédérique. She may be a bit inhuman, but she is not unsympathetic: “To survive in a world of men, she must behave as if playing a game…She has everything I like in a woman, in wild animals, in plants, in rivers: they live their lives with indifference.”

Though full of good things, the concluding sections of Losey’s film—after Frédérique’s return from Japan—are not satisfactory. The book could be of little help here. Vailland’s final chapter is a vaguely Rashomonish series of suppositions on the part of the four narrators as to what has happened or might happen to the Galuchats. It works as a literary jeu d’esprit; it would have never worked as a climax to the film. Personally, I would have preferred to see Lou/Moreau survive, as in the novel. Lou and Frédérique could give all of the men their walking papers, freeing the two women to become lovers.

The inept English subtitles (by Mrs. Losey) rarely capture the tone of the French dialogue. All remarks concerning homosexuality are mistranslated and softened. “He went to Japan with that bowling girl,” will not do for: “He went to Japan with that bitch from the bowling alley.”

The Trout – La Troite (1982)

Directed by: Joseph Losey

Starring: Isabelle Huppert, Jacques Spiesser, Jeanne Moreau, Daniel Olbrychski, Jacques Spiesser, Jean-Paul Roussillon, Lisette Malidor

Screenplay by: Monique Lange

Production Design by: Alexandre Trauner

Cinematography by: Henri Alekan

Film Editing by: Marie Castro-Vasquez

Costume Design by: Annalisa Nasalli-Rocca

Set Decoration by: Hubert de Varine

Music by: Richard Hartley

Distributed by: Gaumont

Release Date: September 22, 1982

Visits: 108