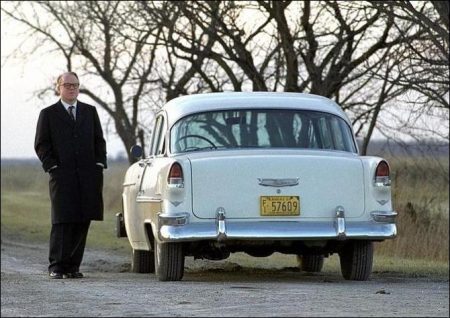

In November, 1959, Truman Capote (Philip Seymour Hoffman), the author of Breakfast at Tiffany’s and a favorite figure in what is soon to be known as the Jet Set, reads an article on a back page of the New York Times. It tells of the murders of four members of a well-known farm family — the Clutters — in Holcomb, Kansas. Similar stories appear in newspapers almost every day, but something about this one catches Capote’s eye.

It presents an opportunity, he believes, to test his long-held theory that, in the hands of the right writer, non-fiction can be as compelling as fiction. What impact have the murders had on that tiny town on the wind-swept plains?

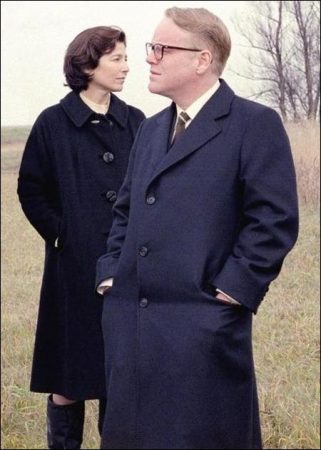

With that as his subject — for his purpose, it does not matter if the murderers are never caught — he convinces The New Yorker magazine to give him an assignment and he sets out for Kansas. Accompanying him is a friend from his Alabama childhood: Harper Lee (Catherine Keener), who within a few months will win a Pulitzer Prize and achieve fame of her own as the author of To Kill a Mockingbird.

Though his childlike voice, fey mannerisms and unconventional clothes arouse initial hostility in a part of the country that still thinks of itself as part of the Old West, Capote quickly wins the trust of the locals, most notably Alvin Dewey (Chris Cooper), the Kansas Bureau of Investigation agent who is leading the hunt for the killers.

A Biographer’s Story by Gerald Clarke

“Truman, I’ve been asked to write your biography. Will you cooperate?” From the other end of the telephone there was a short pause and an even shorter answer—“Sure.” And so I began.

I thought my book would be relatively easy to write. I had, after all, written many profiles of famous and talented people for Time magazine—a list that eventually included everyone from Mae West to Susan Sontag, Elizabeth Taylor to Joseph Campbell. I had also done a series on writers for The Atlantic and Esquire. Gore Vidal. Allen Ginsberg, the Beat poet. Vladmir Nabokov, the creator of Lolita. P. G. Wodehouse, the comic genius behind Jeeves. And, finally, Truman Capote, who was then the most celebrated writer in America—the author of In Cold Blood, the publishing phenomenon of the sixties and a book that has influenced the writing of nonfiction writing ever since. It was that last article that prompted a call from a publisher and my own call to Truman.

I thought my book would take two years, three at most, and that writing it would be a lark, interviews at fancy restaurants and gallons of good vintage wine at the best table in the house. When Truman Capote walked through the door, headwaiters did everything but salaam in their desire to please. “You might say Truman Capote has become omnipotent,” said one newspaper, and for a decade and more he very nearly was.

I was right about the interviews in fancy restaurants and the giddy gallons of Beaujolais. But I was wrong about everything else. If he had known how long In Cold Blood would take, and what it would take out of him, he would not have stopped in Kansas, Truman later said. He would have driven on—“like a bat out of hell.” I sometimes said much the same. What I had not anticipated was the drama that surrounded every minute of Truman’s life, dramas in which I sometimes also became a participant. As a result, my own book took more than thirteen years. Some lark! Writing it was the hardest thing I have ever done. It was also the most exhilarating.

In search of information I crisscrossed the United States and traveled several times to Europe. One of my destinations was of course, Kansas, the setting for In Cold Blood. I came to know all but two of the main characters in Capote, the movie. Harper Lee, who helped Truman with his research and who was soon to have her own hugely successful book, To Kill a Mockingbird. Alvin Dewey, the lead detective for the Kansas Bureau of Investigation, and his wife, Marie. William Shawn, the editor of The New Yorker. And Jack Dunphy, Truman’s longtime companion.

The two I did not interview were the killers, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. They were executed in 1965. But I got to know them—intimately, I thought—through the forty or so letters they wrote to Truman. Most of their letters run several pages, and they are unsparing windows into life on death row. Truman gave them to me, and Dan Futterman, who wrote the screenplay of Capote, is the only one I’ve ever let see them. Their dialogue in the movie reflects, almost word for word, what Perry and Dick actually said.

The movie’s script is all Dan’s—and a very good one it is—but I was happy to answer his questions, large and small. Would Truman have said this? Would he have done that? Bennett Miller, the film’s director, and Philip Seymour Hoffman, who plays Truman, came out to my house on eastern Long Island and asked more questions.

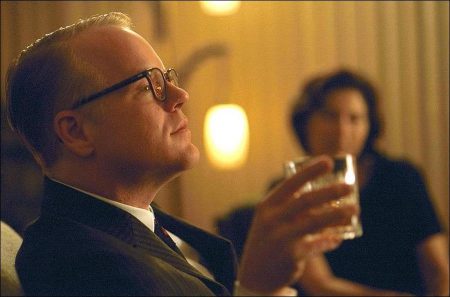

“Did Truman wear his glasses all the time?” was one of the questions Philip asked. (The answer: like a lot of other nearsighted people, Truman often took off his glasses when he was sitting down.) So he could reproduce Truman’s odd, childish voice—Truman did not lisp, as some writers have inaccurately stated—I gave him audio tapes from some of my interviews. Philip did the rest, and through the alchemy a few very gifted actors possess, he has done more than impersonate Truman. For the length of the movie he has resurrected him.

In the last week of June 1984—he died in August—I had lunch with Truman every day on Long Island, followed by long talks at my house or his.

“There’s the one and only T.C.,” he said at one point. “There was nobody like me before, and there ain’t gonna be anybody like me after I’m gone.” That’s true—who could dispute it? For a couple of hours, however, Philip comes close.`

Capote: About “In Cold Blood”

With In Cold Blood, Capote tried to create something entirely new—what he called the “Non-Fiction Novel.” His goal was to bring the techniques of fiction—artistic selection and the novelist’s eye for telling detail—to the writing of non-fiction. He wanted to prove that a factual narrative could be just as gripping as the most imaginative thriller. His success is evident on the very first page, where, with just a few words, he transports the reader to the high plains of western Kansas.

“The land is flat, and the views are awesomely extensive; horses, herds of cattle, a white cluster of grain elevators rising as gracefully as Greek temples are visible long before a traveler reaches them.” By the third page, when four shotgun blasts break the prairie silence, the reader is hooked. “The most perfect writer of my generation,” Norman Mailer had called Capote, and In Cold Blood proved that Mailer had not exaggerated.

It is also hard to exaggerate the influence In Cold Blood was to have on other writers. Until its publication in 1966 “real” writers—writers of talent, in other words—felt they had to follow in the footsteps of Fitzgerald, Hemingway and Faulkner and write fiction. Non-fiction was for historians, journalists and hacks. Capote opened a new path. In the decades that followed many of the best writers in America found their subjects, just as he had done, in the gritty world of real events. Capote’s influence extends even into the twenty-first century, and writers who may never have read In Cold Blood write the way they do because of the way he did.

CAPOTE the film invites you to imagine a time when writers achieved the kind of fame and notoriety that is today associated with pop culture personalities. Americans read more in those days than they do now, and books mattered. More importantly, Truman was a natural born selfpromoter who paved the way for the cult of celebrity that is omnipresent today. His fame cut across all categories, from high to low culture, from literary seriousness to high society frivolity. His name was a constant in newspapers, magazines and TV shows. When he walked around Manhattan, truck drivers would affectionately call to him—”Hey, Truman, how are ya?—and long distance telephone operators would know who he was the instant he picked up the phone.

In 1967, just a year after the book came out, director Richard Brooks came to Holcomb to make a film version. Avoiding Hollywood slickness, Brooks shot in black and white and cast unknowns—Robert Blake and Scott Wilson—as Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. However, he did cast wellknown TV and film actor John Forsythe (later in Charlie’s Angels and Dynasty) as Alvin Dewey. Shooting took place in the Clutter house and other real-life locations. Brooks filmed seven of the original jurors, the actual hangman, and Nancy Clutter’s horse, Babe. Truman arrived during the filming, attracting enormous attention and press coverage, until Brooks, seeing him as a distraction, asked him to leave. Truman obliged, but not before he posed with Blake and Wilson for the cover of Life magazine.

The film opened later that year and was a great commercial and critical success. It was nominated for four Academy Awards: Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay (Brooks), Best Cinematography (Conrad L. Hall) and Best Music (Quincy Jones).

In Cold Blood was filmed again as a Hallmark TV movie in 1996, directed by Jonathan Kaplan (“The Accused”) and starring Sam Neill as Dewey and Eric Roberts and Anthony Edwards as Smith and Hickock. This time the filming took place in Canada.

In Cold Blood brought Capote enormous fame, money and respect. But it also marked another turning point in his life. “In some lives,” wrote Gerald Clarke, “there are moments which, looked at later, can be seen as the lines that define the beginning of a dramatic rise or decline….The proximate cause of his tragic fall—for that’s what it was—was In Cold Blood itself.”

Capote: About Truman Capote

Novelist, short story writer, screenwriter, playwright, creator of the “nonfiction novel,” spellbinding raconteur, wit, superstar, genius and jet-setter, all-around delight, Truman Capote was one of the most astonishing and singular personalities of his time.

He was born Truman Streckfus Persons in New Orleans on September 30th, 1924. His father was Arch Persons, a small-time con man, and his mother was Lillie Mae Faulk Persons, a beautiful young woman from Monroeville, Alabama. As Lillie Mae’s disappointment in Arch grew, she developed a taste for other men, and the marriage fell apart.

In 1930, shortly before his sixth birthday, his parents sent Truman to Monroeville, to stay with his elderly Faulk cousins—three spinster sisters, Jennie, Callie, Sook, and their bachelor brother Bud. Among the Faulk cousins, Truman formed the deepest bond with Sook, who became a kind of surrogate mother. He also found friendship with the girl next door, Harper Lee, his junior by just a year. She would later portray young Truman as the character Dill in her novel To Kill a Mockingbird: “We came to know [him] as a pocket Merlin, whose head teemed with eccentric plans, strange longings, and quaint fancies.”

His mother moved to New York City in 1931. Changing her first name to Nina, she divorced Arch, married Joseph Capote, a Cuban who worked for a textile firm on Wall Street, and brought Truman north to Manhattan.

He attended the Trinity School, a private school on the West Side, and in 1935 he was formally adopted by his stepfather. Truman Persons was now Truman Capote (pronounced Ca-pote-e). In 1939 the Capotes moved to Greenwich, Connecticut, a wealthy suburb of New York, and Truman attended Greenwich High School.

The Capotes returned to New York in 1942 and moved into an apartment on Park Avenue. Truman, who had failed to graduate with his class at Greenwich High School, finally got his diploma from the Franklin School, a private school on the West Side, in 1943. This was to be the end of his formal education.

While attending Franklin, he took a job as the art department copyboy at The New Yorker. A “gorgeous apparition, fluttering, flitting up and down the corridors of the magazine,” was how Brendan Gill, one of the magazine’s stalwarts, described him. During a period when homosexuality was anathema in America, Truman was nonchalantly and resplendently gay.

Truman had been writing stories from an early age and he hoped that The New Yorker would publish him. But all his efforts were rebuffed. He found a kinder reception at two women’s magazines, Mademoiselle and Harper’s Bazaar, which in those days published the best short fiction in America. His first story in Mademoiselle was “Miriam,” which not only won him an O. Henry Award but attracted great attention in Gotham’s literary circles. Other stories soon followed and in 1945 Random House gave him a contract for his first novel—Other Voices, Other Rooms, he was to title it.

Unable to write at home—his mother had turned into an abusive alcoholic—Truman received a fellowship to Yaddo, a retreat for artists, writers and composers in upstate New York.

There he began a long relationship with Newton Arvin, a professor of literature at Smith College in Massachusetts. Twenty-four years older than Truman, Arvin was a graceful writer, a scholar of impressive erudition and a critic of impeccable judgment. His biography of Herman Melville was to win the very first National Book Award for non-fiction. Both lover and father figure, Arvin, Truman later said, was also his Yale and Harvard.

Though it had only modest sales, Other Voices, Other Rooms, which was published in 1948, cemented Truman’s reputation as one of the most promising writers of the post World War II generation. Never explicit, it is, in fact, the story of a teenage boy’s awakening knowledge of his homosexuality. It was not until much later that Capote himself was able to recognize that it was his spiritual, if not his factual, autobiography. Gerald Clarke wrote that the lead character’s eccentric cousin “became the spokesman for the themes that dominate all of Truman’s writing: the loneliness that afflicts all but the stupid or insensitive; the sacredness of love, whatever its form; the disappointment that invariably follows high expectation; and the perversion of innocence.”

In the fall of 1948, after a summer in Europe, Truman met Jack Dunphy, a fellow writer who became his lifelong companion. In 1950 they settled in Taormina, Sicily—in a house once inhabited by D.H. Lawrence—and Truman began work on his second novel, The Grass Harp.

If Other Voices, Other Rooms was Capote’s look at the dark side of his childhood, The Grass Harp (1951) was, in Clarke’s words, “an attempt to raise the bittersweet spirits of remembrance and nostalgia.” In this story of a lonely boy who finds refuge in a tree house with four other displaced spirits, Truman conjured up the memory of his childhood in Alabama and his beloved elderly cousin, Sook Faulk. Truman adapted The Grass Harp for Broadway the following year, but, with a run of only a month, it was not a commercial success. (A movie version, starring Walter Matthau and Sissy Spacek, was filmed in 1997.)

After doing some rewriting on the screenplay of Vittorio de Sica’s Indiscretion of an American Wife (1952), Truman collaborated with director John Huston on the offbeat mystery-comedy Beat the Devil (1953). Filmed in Ravello, Italy, and starring Jennifer Jones, Humphrey Bogart, and Gina Lollobrigida, it is as quirky and light-hearted to watch as it was to make. (Capote considered his best screenplay, however, to be that of The Innocents, an adaptation of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw that was released in 1961 and starred Deborah Kerr.) After Beat the Devil, Jack and Truman went to Portofino, Italy, where Truman adapted his short story, “House of Flowers,” into a Broadway musical. Though the score is one of Harold Arlen’s best, the show had only modest success.

Truman returned to Europe, but in January, 1954, he was forced to fly back to New York after his mother swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills. She died before he arrived.

Capote’s interest in the possibilities of journalism led to the writing of The Muses Are Heard, the story of a Porgy and Bess troupe’s visit to the Soviet Union, and “The Duke in His Domain,” a long and revealing profile of Marlon Brando. After reading it, the actor professed a desire to murder him.

Truman’s next book, Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1958), created a luminescent, unforgettable heroine in Holly Golightly, a free-spirited sprite in wartime Manhattan. Holly’s only anxiety is what she calls the “mean reds.” Her solution: “What I’ve found does the most good is to just get into a taxi and go to Tiffany’s,” she says. “It calms me down right away, the quietness and the proud look of it: nothing very bad could happen to you there…” The film was made into a classic film directed by Blake Edwards, featuring Audrey Hepburn, Henry Mancini’s song “Moon River, and a grafted-on love story. Truman, while a fan of Hepburn’s, thought she had been miscast and was disappointed in the film; he felt Marilyn Monroe would have been a better choice. None of the film’s legions of fans agreed with him.

In November, 1959, Capote read about the Clutter murders in the New York Times. Thus began In Cold Blood (1966) a project which would take six years of his life. Those are the years that are explored by writer Dan Futterman and director Bennett Miller in their film, Capote.

After the long, intense years writing In Cold Blood, Capote gave himself a party, and on November 28th, 1966, he threw one of the most spectacular bashes in the history of New York –the Black and White Ball at the Plaza Hotel. Given in honor of Washington Post publisher Katherine Graham, who was then the most powerful woman in the country, the gala celebration began at ten and went until breakfast the following morning.

Approximately five hundred people from the most stellar reaches of the glitterati were invited, with a precise dress code: men in black tie, with black mask; women in black or white dress, white mask, plus a fan. The beau monde blowout created front page news all over the country. “An extraordinary thing in its way,” Truman said later, “but as far as I was concerned it was just a private party and nobody’s business.”

During the writing of In Cold Blood, Capote began to drink heavily and take pills. He seemed to lose focus and direct his energies more towards the high life rather than high art. He announced the title of his next novel—Answered Prayers—and said that it would have a scope equal to Proust’s. But when the first chapter was published in Esquire in 1975, it unleashed an angry backlash from some of his rich friends, who were furious to see themselves as thinly disguised characters. They felt betrayed and many, including the wife of CBS chairman Bill Paley—Babe Paley, the woman he loved most of all—refused to forgive or see him. Given the nickname “The Tiny Terror,” he was a social pariah, and this public shunning added to his downward spiral with drugs and alcohol.

Even his relationship with Jack Dunphy suffered, and Truman sought out affection from a series of unremarkable men. All of these relationships ended badly. Yet, with all of that, the alcohol, the drugs and the depression, he could still write—and write very well indeed—and his last book, a collection titled Music for Chameleons (1980), contains prose any writer might envy.

Truman Capote died in Los Angeles on August 25th, 1984 a month shy of his sixtieth birthday.

Capote (2005)

Directed by: Bennett Miller

Starring: Philip Seymour Hoffman, Catherine Keener, Clifton Collins Jr, Mark Pellegrino, Bruce Greenwood, Andrew Farago, Chris Cooper, David Wilson Barnes, Rob McLaughlin

Screenplay by: Dan Futterman

Production Design by: Jess Gonchor

Cinematography by: Adam Kimmel

Film Editing by: Christopher Tellefsen

Costume Design by: Kasia Walicka-Maimone

Set Decoration by: Maryam Decter, Scott Rossell

Art Direction by: Gord Peterson

Music by: Mychael Danna

MPAA Rating: R for some violent images and brief strong language.

Distributed by: Sony Pictures Classics

Release Date: September 30, 2005

Views: 76