All about Bob Marley. Given the mixed feelings many Jamaican performers, and the Rastafarians especially, have about the music business culture they came up in, enlisting Bunny and some others was no simple task. “It took us many, many months. He was suspicious and felt the story of the original Wailers had not been told accurately in the past.

And he feels that, as the last survivor of the Wailers, he wants to shape that history, understandably, because he feels he, and the story, have been misrepresented. It took a long time to persuade him that we wanted to make a fair and balanced film, and the people putting up the money to make the film don’t actually have the final say. This is a completely independent project.

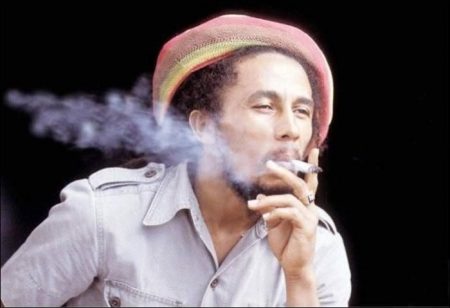

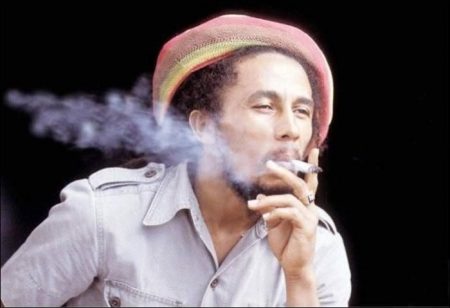

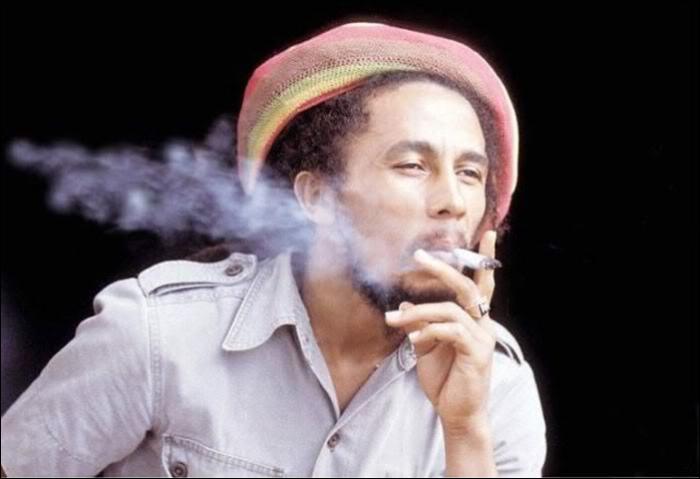

“Once Bunny signed on, he gave the interview a full and willing day, and came appropriately robed, and accessorized,” says Macdonald. “He’s very conscious of his look and the thing that I was most impressed with was the pipe that he had with him, which was made out of a carrot. He clutched this carrot all day. And I said, ‘What is the carrot?’ He said, ‘it’s my pipe,’ and he was puffing on this all day. That seemed highly appropriate for a man called Bunny.”

“An important part of the process was to discover people like Dudley Sibley, who’s the recording artist, and studio janitor, in Studio One, and lived with Bob for a year or two in the back room there. Nobody had ever interviewed him before – perhaps they felt he was kind of a goofy-looking guy who’s maybe a little crazy. But actually he was fascinating and his memories were unsullied, and he had this firsthand insight of living cheek by jowl with Bob in this room before he was Bob, as it were.”

The filmmaker’s exhaustive interviewing process resulted in a number of other unexpected – and otherwise unavailable – revelations, including from Bob’s close white cousin Peter, who Macdonald says “nobody had thought to speak with before.”

“A real key for me,” says Macdonald, “was trying to understand the importance to Bob’s life that he was of mixed race. It’s hard for some of us in both Europe and America to understand the stigma attached to that. And Bob, coming as he did from the deep countryside in his own day, one of the truly black parts of Jamaica, felt that stigma attached to being of mixed race, and not just from the white side of the island but also from the black side.”

Cedella says that she felt confident that Macdonald, perhaps best known for illuminating both the mythic and shabby sides of dictator Idi Amin as portrayed on film by Forrest Whitaker, would delve knowledgeably into the issues of race and colonialism that ran as threads throughout Jamaican life, from the island’s harsh colonial legacy through the rise of Rastafarianism.

“By coincidence I had just watched The Last King of Scotland when Chris called me and said, `Listen, I have this director in mind.’ And when he told me, I said, `Really? I just watched something that he made, and it was just so real.’”

Cedella was particularly struck by the presence of Bob’s half-sister, Constance, who is depicted in the film listening to the song “Cornerstone,” written by Bob after an unsatisfactory and remote meeting with his white uncle. Constance was clearly moved. “I’m glad Auntie Constance was in here,” says Cedella. “She knew Grandpa’s [Norval Marley] family better than Dad did.”

The director’s access to the Marley family proved invaluable when it came to understanding many of the deeply moving and sometimes surprising truths about Bob’s life and relationships which their conversations revealed – many tremendously personal details, which brought to the film, for the first time, a full and rounded portrait of the musician and the man.

Macdonald found himself touched by the grace Rita Marley showed in speaking of Bob’s rather wandering eye. Of Rita, Macdonald says: “She comes out of the film to me as someone who’s quite noble in a way, because she’s clearly had to put up with a lot on a personal level. You feel [Bob] obviously caused her pain and caused Cedella, their daughter, pain in the way he had behaved. But they not only forgive it, they clearly feel that what he was doing was so important, and that the message that he was spreading was so much more important than those details of personal feeling.”

Rita’s words in the film only deepened Cedella’s respect for her mother. “I said to her, `Mom, they don’t make women like you anymore.’ I guess, back in the ’60s, when you fall in love like that, you fall in love, you know? There are days when I go into my mom’s room and she’ll be talking and I know there’s nobody in the room. So I’ll knock on the door and I’ll say, `Mom, who are you talking to?’ And she will say, `Oh, my boyfriend, Robbie.’ That’s what she called Dad. ‘What are you guys talking about?’ And she says, `I’m just making sure he’s taking care of himself.’ She just loves my dad. She loves him. It’s not that she’s not going to get angry if he’s doing what he’s doing, you know? But she loves him beyond that.”

Among the other interviews conducted was one with the legendarily private and diffident Chris Blackwell, who, Cedella says, was vigilant in keeping the focus on the star and not the Island Records label head who guided him. “He’s always telling me, ‘You know I never liked taking a picture with Bob’,” remembers Cedella, “but Dad respected Chris and his ear.”

For Marley’s son Ziggy, the key revelatory moment in the film is the testimony of the nurse who shepherded his father through some of the agonizing final days of his terminal cancer in a European clinic. “Some of that I hadn’t heard or seen before, and that was very emotional and insightful,” he says.

“I think what’s great about the film,” Ziggy continues, “is though there’s been a lot of things done on Bob, I think this one will give people a more emotional connection to Bob’s life as a man. Not just as a reggae legend or a mythical figure, but his life as a man, you know? The struggles he went through.”

Macdonald’s summation of MARLEY is a testament to the deeper insight he has achieved: “I feel that that one of the reasons Bob has lived on is because he speaks to the oppressed people of the world, be they in the United States, or Britain or Germany, but more than anything else, he speaks to people in the developing world who feel like they’ve been given a bum deal, who feel like they’ve been hopped over by the west or whatever. And here’s a voice telling them, `Your turn will come. You’re down now but you’re going to get up there.’”

Views: 136