Rosa Luxemburg movie storyline. Wronke Prison, 1916. Social democrat Rosa Luxemburg faces a mock execution. Twenty years earlier, Rosa’s political gifts are acknowledged by everyone, as she struggles for democratic government in Germany and revolution in Poland. There she works closely with Leo Jogiches.

Their political activity creates some difficulty for their personal relationship… As international tensions rise, Rosa makes speeches denouncing war and militarism. She seems too radical for her fellow Socialists. She meets Karl Liebknecht. When World War I begins, Rosa and Karl are united in opposition.

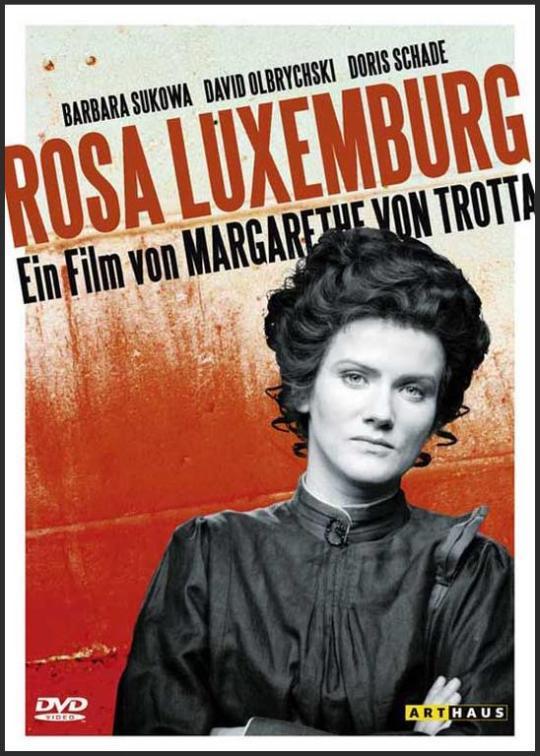

Rosa Luxemburg (German: Die Geduld der Rosa Luxemburg) is a 1986 West German drama film directed by Margarethe von Trotta. The film received the 1986 German Film Award for Best Feature Film (Bester Spielfilm), and Barbara Sukowa won the Cannes Film Festival’s Best Actress Award and the German Film Award for Best Actress for her performance as Rosa Luxemburg.

Rosa Luxemburg: New Light on Early Leftist

LEAD: WHEN she was murdered in Berlin on the night of Jan. 15, 1919, Rosa Luxemburg – flippantly referred to as Red Rosa by both friends and enemies – had been one of the leading figures of the European left for over 20 years. She was 49. Two weeks earlier, the woman who preached unity in the ranks (though she’d angrily broken away from the German Social Democrats five years before), joined with the members of her splinter group, the Spartacists, to found the German Communist.

WHEN she was murdered in Berlin on the night of Jan. 15, 1919, Rosa Luxemburg – flippantly referred to as Red Rosa by both friends and enemies – had been one of the leading figures of the European left for over 20 years. She was 49. Two weeks earlier, the woman who preached unity in the ranks (though she’d angrily broken away from the German Social Democrats five years before), joined with the members of her splinter group, the Spartacists, to found the German Communist Party.

Her death was probably as much of a relief to Lenin and the Bolsheviks in Moscow, whom she relentlessly criticized for their autocratic programs, as it was to her former comrades in the Social Democratic Party, who authorized the purge of the ultraleft Spartacists and orchestrated the cover-up of her murder.

Rosa Luxemburg is one of the most fascinating figures in modern European political history, and today one of the least known, at least in the United States. In both East and West Germany her name is usually invoked in ways that carefully omit those aspects of the Luxemburg creed that don’t fit the political fashions of the moment.

She was a purist. She clung to Marx’s teachings (as she perceived them) when Lenin, in Russia, and Bernstein, in Germany, were rewriting the master to fit their own particular needs. She believed in the dictatorship of the proletariat but said that no cause could justify the taking of one innocent life.

There’s no way Margarethe von Trotta’s seriously conceived new film, ”Rosa Luxemburg,” which opens today at the Lincoln Plaza 3, can set the record straight on this complex woman. No film could.

Even Elzbieta Ettinger, the author of a new biography (”Rosa Luxemburg,” published by Beacon Press), admits the impossibility of telling the entire story. “There is no such thing as ‘definitive biography,’ ” Miss Ettinger writes in her preface. “A biography is always a selection and therefore a biographer is always ‘biased.’ ”

Miss von Trotta’s film, with a fine, soberly intelligent performance by Barbara Sukowa (the seductive star of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s “Lola”), is a first-rate introduction to an extremely complicated personality. It’s necessarily simplified, as well as biased on behalf of those aspects of Luxemburg that will speak most clearly to today’s audiences.

The movie concentrates on her abhorrence of violence, though her own Spartacists were not exactly nonviolent. It dramatizes her pacifism and her break with the German Social Democrats when, at the start of the war, they embraced the Kaiser’s militarism, thus abandoning the concept of the international brotherhood of the proletariat. (In 1915 she suggested a new ending for “The Communist Manifesto”: “Workers of all countries unite in peacetime, but in war – slit one another’s throats!”) Miss von Trotta and Miss Sukowa try to emphasize Luxemburg’s womanliness, though her lovers, in the film as in her life, never are a match for her. Leo Jogiches, her first and greatest love (a fiery revolutionary who answered her passionate letters with political tracts), is played by the excellent Polish actor Daniel Olbrychski as a handsome, dimly seen weakling. The other men are ciphers.

The film is, surprisingly, most effective when Luxemburg is alone, either in one of her many prison cells, with her thoughts being heard on the soundtrack, or speaking on the political platform. The Luxemburg words are still rousing, whether she is describing her idea of “spontaneous revolution” (as opposed to revolution imposed on the masses by the intelligentsia) or heaping sarcasm on revisionist members of the Social Democratic Party.

Miss Sukowa, whose pronounced jaw here seems to be made of steel (though the rest of her is desperately frail), delivers the speeches with such conviction that Luxemburg’s apparent failure at the end becomes genuinely moving.

Otherwise, however, this Luxemburg appears to exist in a community of strangers. Miss von Trotta simply hasn’t the means or the time to characterize the people around her. The film’s fractured chronology doesn’t help. Missing, too, is a sense of Luxemburg’s many contradictions, which, as much as her love life and her longing for conventional domesticity, make her such an alluring subject for the biographer.

Though she was a spectacular demonstration of the liberated woman, she had little interest in organized feminism. She preferred to devote herself to ‘”larger” issues. She was a Polish-born Jew who, as a child, had survived a pogrom and, throughout her life, suffered other forms of anti-Semitism. Yet she saw the Jewish cause as only another expression of the dreaded nationalism that divided the working classes and kept them in bondage. In one way or another, at one point and another, she succeeded in alienating just about everybody.

The film is rich with period detail, though Miss von Trotta never allows this to get in the way. The film has a clean, uncluttered look. In spite of the narrative ellipses and the simplification of issues, there’s never any doubt that “Rosa Luxemburg” is about a most remarkable woman.

Rosa Luxemburg (1986)

Directed by: Margarethe von Trotta

Starring: Barbara Sukowa, Daniel Olbrychski, Otto Sander, Adelheid Arndt, Jürgen Holtz, Doris Schade, Hannes Jaenicke, Jan Biczycki, Barbara Lass, Patrizia Lazreg

Screenplay by: Margarethe von Trotta

Cinematography by: Franz Rath

Film Editing by: Dagmar Hirtz, Galip Iyitanir

Costume Design by: Monika Hasse

Set Decoration by: Stepan Exner, Bernd Lepel

Music by: Nicolas Economou

Distributed by: New Yorker Films

Release Date: April 10, 1986

Views: 227