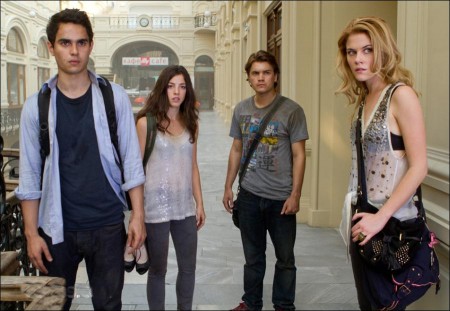

The Darkest Hour: Aliens in Moscow. The Darkest Hour began as the seed of an idea often discussed by producer Tom Jacobson and executive producer Monnie Wills. “About five years ago, we were talking about what would it be like to survive in the wake of an alien apocalypse where we lost?” explains Jacobson.

“What happens the day after Independence Day? We were interested in a story that is focused just on the characters. Where were they? I like stories about humanity and science fiction, with the classic themes such as ordinary people in the midst of extraordinary circumstances. What would happen if we were attacked, conquered, and occupied? That was the genesis of the idea.”

“I also like the notion of people in an occupied territory who don’t capitulate, like French resistance movies,” adds Jacobson. “So this is also somewhat inspired by those great World War II movies, except instead of German lines, we’re behind enemy lines of an alien occupation. That whole genre allows you to explore heroism and how you behave when you’re tested. In a theatrical world, the best science fiction can heighten those themes and therefore is very entertaining to an audience.”

Jacobson turned to his old friend Leslie Bohem, and his young writing partner, M.T. Ahern, to flesh out the concepts. “They took that shred of the idea, invented the story, and came up with the title The Darkest Hour,” says Jacobson. “It then evolved in a lot of different directions. Les and Megan wrote a really great story about human survival, which I sold to New Regency, and then the thought came up of adding a surprising and unique element to it. Through all of these science fiction or war narratives, we’ve seen versions of everything, so let’s add an original layer.”

“A big decision was made. From page one, let’s set it in Moscow,” reveals Jacobson. “This is one of those huge ideas that changed everything… who the characters were and why would we be in Moscow. They come to this exciting vibrant city that a lot of people have heard about, but most people, especially most Americans, haven’t been there. Moscow seemed like the type of place that young characters might adventure to,” says Jacobson. “We were all excited by making it about a group of people who are already strangers in a strange land, and when the aliens come, just became even stranger.”

Screenwriter Jon Spaihts began work on a whole new script set in Moscow and Moscow-based filmmaker Timur Bekmambetov, who directed the global hits Wanted and Night Watch, joined the project as a producer. “Partnering with Timur Bekmambetov was very exciting because he loved the science fiction and visual elements of the movie,” says Jacobson. “Plus Timur has an insider’s view of filmmaking in Moscow.”

The groundbreaking director was happy to participate as a producer. “Producing and directing for me, is almost the same. When you’re directing, you’re not shooting, you’re not acting yourself, you’re not dressing actors… you’re directing,” explains Bekmambetov. “The producer is also managing processes – people and expectations – so for me to produce means you have the movie in your head and you have to find the right people to make it. It’s almost the same thing. You’re not screaming rolling on the set, but you’re still finding the right people and the right strategy.”

“Originally, maybe 4 years ago, it was scripted in a small American town. The first time I spoke with Tom Jacobson, I said ‘Can we move it to Moscow?’ When you change the point of view it becomes an interesting project immediately. Like King Kong in Moscow would be a big deal, King Kong in New York nobody wants to play that game because it’s been done,” comments Bekmambetov. “It’s still quite intriguing for the viewer to be here because not so many western movies are made in Moscow, it makes the movie cool immediately.”

“Moscow is a unique environment and very interesting visually because it’s unusual. Moscow is not as pretty as Paris, not as big as Manhattan, but it has it’s own tone and light. If you move any conventional, classic story to Moscow, it immediately becomes something interesting,” reiterates Bekmambetov. “Second, we have the Russian culture, we have history of Russian filmmaking that’s different, and somehow it’s influenced the movies made in Russia. The audience will enjoy it and will feel it’s something new. The formula of a successful project has to be relatable story in a unique world. If you have a good story and you can shoot it in Moscow, then you have an interesting film, like District 9 in Johannesburg, South Africa.”

“The location itself became part of the storytelling power,” adds Jacobson. “Visually Moscow has force and power in the architecture that we wanted to capture, and we see it through a foreigner’s point of view. Moscow also has a reputation as a wild place, with a lot of nightlife and a lot of money. We also wanted to capture that new Wild West feeling here… the excitement, gloss, glamour, noise, music, and dynamism of the city… and then contrast that with the silence after the fall.”

“Timur has this fantastic vision and imagination, but he also has this great group of people working with him at his company Bazelev who are doing a lot of our visual effects. Very early we started visual development and they did a lot of concept art and animatics – or pre-viz – of key elements,” explains Jacobson. “The movie was about the idea and then about the visualization and execution of the idea. So Timur’s visual effects team in Moscow started the work almost two and a half years before shooting and generated a lot of images that gave a sense of the movie.”

“They created early concepts of the aliens and a general proof of concept look of a depopulated Moscow, because that was one of the big elements, to take a huge international city of 14 million people and empty it,” adds Jacobson. “Later in the movie, the characters also discover the aliens are doing something here. There are manufacturing works and we came up with the designs for those alien towers. This early concept art was a palate of opportunity for the director, who started guiding that work when he started on the movie.”

About a year before shooting began, director Chris Gorak was selected to helm the project. “I was excited to get in business with Chris because I loved his movie Right At Your Door. I thought it was authentic, sincere, scary, believable, the actors were great in it, and the story was told with conviction,” says Jacobson.

“Chris read our script, was interested, and everything he said about it felt right and then some. Specifically about certain areas of the storytelling, like how the characters move through the story. Chris felt their journey of realization was really important… what they learn about the aliens and about their own circumstances drives the emotion of the story. The window into story is through our characters. The narrative point of view of the movie is to follow them as they figure out what’s going on,” explains Jacobson.

“The Darkest Hour is only his time directing, but Chris has really brought something interesting because he really comes from a place of character,” agrees Wills. “He really spent a lot of time thinking about and working with the actors about their experiences here… what it means to be in Moscow and to really make these characters come alive. Chris also comes from a production design and art director background, so he’s really been able to stage the film to not only take advantage of Moscow, but to put our characters into the middle of a very believable, post-apocalyptic city.”

“Since I’m very comfortable with the visual aspects of filmmaking, I can focus on script, character, and telling the right story, and the other stuff is second nature,” says Gorak. “But Moscow was one of the first things that I got really excited about. First was the alien and how it interacted with our world, but second was Moscow itself as a location. The city added a whole other texture and character in the film that’s irreplaceable.”

“Historically Moscow is a standalone culture and in an area of Europe that really is like the last frontier. We wanted to put our group of travelers in a place where it’s unbalanced for them. Moscow is that plus it offers so much richness and density,” says Gorak. “In addition, Russian is a foreign language for everyone in the movie. Moscow is this island of opportunity for a young westerner, yet they can’t read a street sign because they are written in the Cyrillic alphabet, so they don’t know which way to go. That creates a fish out of water survival story.”

“There have been so many alien invasion films and Moscow gave a fresh layer to the concept. I have never been here before, and now I’m here destroying it,” laughs Gorak. “I was really excited to explore Moscow and find all the iconic locations, work with the team here, and build a version of Moscow that has never been seen before.”

“It was very important for Chris to actually take a journey as a filmmaker as he was prepping the movie, to learn the city and pick the places that he felt had power that would impact the characters standing in front of something very massive, powerful and beautiful, and sometimes beautiful in a brutal way. Hopefully, in the same way it will impact the audience,” adds Jacobson.

“When we were scouting for locations, the Russian crew was a little resistant to my wanting to shoot all the iconic places that I’ve never seen in an American film. To them picking Red Square is like us shooting the Statue of Liberty, Times Square, or the Hollywood sign. But I wanted all the postcard shots and I wanted to put out characters and our story inside that postcard. I wanted Red Square, the Patriarch Bridge, the Church of Christ… all this really iconic Russian architecture. All this stuff that makes up Moscow, makes it so rich and so vibrant. Learning about the history as we were filming was just incredible and I knew it was going to add so much texture that a large majority of this audience would never experience in person, never mind in an alien invasion film.”

Jacobson adds, “Chris obviously has a great eye and a great vision. His visual skill set was this incredible bonus that you see in the movie, especially the locations. When we came to Moscow, it’s like any huge international city – Rome, Paris, London, New York – in that it’s a hard city to shoot because it is huge and has civic rules. Chris really challenged the production because he wanted to shoot an international movie in a narrative way by putting the characters and the story into these backgrounds to make it feel real. He wanted to shoot Moscow in a way that hasn’t been seen before.” The director’s energy helped keep the challenging location shoot together.

“Chris Gorak has not stopped moving since the day that he landed in Moscow,” laughs Wills. “There’s no one on our crew that is working harder and that leadership from a director really encourages the rest of the crew to step up. We have a limited amount of time that we can be in these locations and a lot that we want to get, so every second counts. It makes a difference when your director is leading the charge.”

Gorak was particularly attracted to the unique take on the science fiction parts of the story. “The content was really interesting. Being a science fiction cinema fan, when I first got the script for this project I was attracted to this idea of the apocalypse, but mostly to what the aliens are,” shares Gorak. “I was really attracted to their invisible nature and the unique concept of how they affect the electricity of the environment. I felt a great challenge in how to present that cinematically.”

“The deadly nature of these aliens comes from the fact that they are, for the most part, invisible. When they strike it’s instant, deadly, and irreversible. The big idea is that they are electrical creatures, which is something the characters discover along the way,” says Jacobson. “Even though it is science fiction logic, we wanted it to be credible. So we spent a lot of time, especially when Chris Gorak came on, embedding the science. These are creatures of some combination of mechanical and electromagnetic, and their blood is electricity. We came up with this concept that they generate this shield that renders them invisible. That shield has a dual purpose – a defensive and an offensive weapon.”

After hiding through the initial attack, the main characters emerge and begin searching for other survivors. “The creatures have blasted the entire planet into the Stone Age. There’s no electricity, no phone works, nothing… it’s the Dark Ages. Our characters don’t know what has happened,” states Jacobson.

The survivors travel across a deserted Moscow to find help, all the while trying to evade the enemy. “The aliens send out a wave energy that ripples through the environment and ignites everything that conducts electricity. That’s how it searches and sees. It’s not x-ray, it’s not infrared… it’s something new,” adds Gorak.

“I was really excited that his project flips the terror genre on its head… light is more dangerous than dark,” explains Gorak. “In this genre, dark is usually the scariest, but now because the aliens are invisible yet illuminate lights as they come near, the light bulb becomes a marker of danger. So it’s actually safer to travel at night, avoid the light and stay in the darkness. Daytime is now scary.”

“The aliens’ interaction with lights, any electrical device, creates this reverse scare, because normally light is safety. But in our movie, it means that danger is coming,” agrees Jacobson. “When an alien is near that light, it’ll flicker on, without any connection to any power source, because the alien itself generates that power. The characters figure this out for themselves, and they then start to smartly think of light bulbs or radios or flashlights or cell phones as early warning devices.”

The aliens’ weapon of choice is the shred. “One of the great aspects of our enemy is that they have this very violent attack protocol. The aliens shred human beings with an instant cauterization of our particles… ashing the body into dust. The shred is a very violent, organic and sloppy process, and it’s never perfect. No two shreds are the same,” explains Gorak. “It’s grounded in physics and that grounds the movie, making for a real danger for our audience to experience. “

“Shredding is like a wood chipper or a belt sander,” adds Jacobson. “It all comes back to the concept that it’s electrical in nature, so the shredding is more like being disintegrated by a bolt of lightning. Since we wanted to go for a PG-13 rating, there was a lot of visual development on the intensity of the shred. We wanted to have an adventure feel, as opposed to a straight horror feel. We didn’t want it to be gory, we wanted it to have a science base.”

The audience sees the aliens’ point of view when it is hunting survivors. “In the original script there was no point of view (POV) of the alien, that was an element that Chris Gorak brought. We started to realize that when you’re dealing with something invisible, you need to signal to the audience some threat. Where is this thing? By giving it a POV, we really clued into this idea that there is an intelligence there, that humans are being hunted; this isn’t just some random occurrence. There’s a thinking breathing something that is after our people. These aliens are not seeing your heat signature or your bones, they’re actually seeing the electrical pulses that move through your body, emanating out of the brain and down the spine. Once we hit on that idea, it just fell into place.”

Bekmambetov offered practical and creative guidance to Gorak in prepping the shoot, but did not spend a lot of time on the Moscow set once the cameras rolled. “I’m trying to stay away from the set,” admits Bekmambetov. “It’s quite a unique experience, because I’ve never before been a producer of an American movie. I’m trying to protect Chris, to let him play his own game and be creative. I can help him to understand Russian realities and to be sure this movie will be correct emotionally for Russian audiences. We spent a lot of time with the Russian visual effects people here to develop pre-visualizations and art concepts and I was helping to make it happen. As a producer, I never planned or wanted to direct it. This is a story about American kids in Moscow… it’s better that Chris will tell the story, because he is an American kid in Moscow.”

“Timur and his team have been fantastic collaborators throughout the process. Early on, Tom, Monnie and I meet with Timur at his house in Los Angeles and had creative sessions that were really productive,” says Gorak. “Timur is an incredible creative filmmaker in his own right, and he added touches to our alien design, movement, and activity. Their subtle existence and dangers of the alien and how to present that to the audience.”

Gorak continues, “Timur always adds that little touch to make it special… he’s really good at that. What was the enemy and what were the rules of the enemy. Timur likes to police the mythology of the science fiction. What are these aliens, what are they made up of, what do they want? We had a lot of discussions about that, which then leads to those fun moments in the story for example, of scattering light bulbs as a warning device. Those kinds of moments that Timur adds can become classic indelible images.”

Jacobson adds, “It’s been a really good combination because Chris brings this really grounded reality to put our character in, and our partnership with Timur brings a theatricality and a flash. Certainly his producing of this inside Moscow has been incredibly helpful. Timur’s work brings us dynamics and imagination to this very original vision.”

During the development of The Darkest Hour, James Cameron’s groundbreaking 3D film Avatar was released to overwhelming critical, financial, and creative success. “Originally The Darkest Hour was a 2D movie in my head, but when Avatar came out, the studios started really thinking about which properties could be 3D. So in the spring of 2010 we shot some 3D tests in Los Angeles to see how 3D fit with what we were trying to create. Quite honestly I was reluctant because I had a different film in my head for so long. Once we played with the 3D equipment, cut that test night shoot together, worked with it in post putting in some visual effects, and projected in on screen… I just changed,” admits Gorak.

“Going 3D was quite ambitious because it costs more money,” adds Bekmambetov. “It was a very brave decision to shoot in 3D and not convert later, because it changed the whole production plan and made us rethink all these shots. The choreography of the 3D shots is another language from a 2D movie. It’s the beginning for 3D and some of this language doesn’t exist yet. Every new 3D movie, it is one step forward to develop this language. We have to learn how to do this, but also we have to teach audiences how to consume, because it’s very different. But it’s good because we have a chance to play with these new toys and figure out how it works.”

“We chose to shoot 3D to really capture one, the environment of this incredible city, and two our alien itself and the way it behaves and shreds. We thought the electrical nature of the aliens would be fantastic in 3D. To us, Moscow is the new Pandora. To be the first film to shoot 3D here is a great opportunity that we didn’t want to miss,” shares Gorak.

“When you commit to shooting a film in 3D, you want to deliver a level of experience that you’re just not going to get in 2D, or else what is the point?” asks Wills “The ability to project the ash out into the audience was something that we keyed in on very early and wanted to make a part of that 3D experience.”

“Shooting in 3D has an immersive quality to it. I like to call it innovative dynamic immersion, or IDI. It’s not about 3 dimensions… it’s about four, five, or six dimensions. It’s HD on steroids where you’re in the environment and the environment is shaped in a different way for the viewing audience. Grabbing the characters and sticking them in the lap of the audience, and grabbing the audience and sticking them in the environment is what it’s about,” says Gorak.

“The movie is going to be a real strong emotional and thrilling ride. Once out characters come out of their shelter and try to find their way across the city, it’s pretty relentless. Chris and our director of photography Scott Kevan specifically designed shots with a lot of depth behind the characters so you’ll feel like you’re there, like you’re in it,” describes Jacobson. “It’s a natural for this movie to be 3D because the story has an adventure quality and a journey part to it – those elements play really well in 3D. We’re also trying to shoot in this naturalistic action way that we don’t think has been done a lot in 3D. You’ve seen grand fantasy science fiction movies, family movies, and video game movies shot in 3D, but we haven’t really seen a grounded adventure movie in 3D yet.”

Just prior to the start of filming, acclaimed visual effects supervisor Stefen Fangmeier joined the creative team. “Timur was instrumental in developing some of the early concepts – the way that we could define the aliens movement by being electric, lighting the things around it, the shred, and some of the lightening that it shoots. But when it came time to actually execute that, Stefen has been very instrumental in helping us to really integrate the production into those visual effects. It’s very important that it not feel too CG. It needs to feel like it is really happening,” says Wills.

“Stefen’s input on the film is priceless,” states Gorak. “He added a great level of creativity and detail to the film that comes from his years of experience and his experience as a director. He had some great suggestions, not only on set, but also in post as we developed the alien further and how an alien would come towards the camera in 3D.”

Jacobson comments, “Stefen helped with how to embed those visual effects in the movie to achieve this combination of reality that we wanted. This is taking place in the real world, but also should have scale and have a grounded wow factor – we wanted to feel like it’s really happening to these people. The alien itself, the alien action, the alien towers, and the way the aliens land, all have some spectacle to it, but in this real world.”

“When we started working with Timur, he had this very talented team at Bazelev led by visual effects supervisor Dmitry Tokoyako, who was really guiding this, and then along the way Stefen Fangmeier came and they made a fantastic team,” adds Jacobson. “Stefen and Dmitry bring a real understanding of what this could be,” agrees Gorak. “There’s a very subtle nature to the design of this creature where the alien isn’t revealed on page one. There is a long reveal of what the alien is, how much you see of this alien, and how our heroes start to understand it. Once they understand the physics of this alien, they can start to fight back. Our journey takes us through that understanding and I feel Stefen and his team fully grasped that and how to hide the ball.”

“The 3D helps to create these epic stages for an intimate story. The core is the relationship between people, that’s a dramatic spine of the movie, what makes the movie emotional,” says Bekmambetov. “But the scope gives you the scale and the background. This is very unique because the 3D makes the experience about being there. I hope this movie will give audience a chance to literally feel what’s happening when a huge disaster happens. It’s the first movie when you see the world in this destroyed in 3D.”

Shooting in 3D makes the job of the actors even more crucial. “It’s very important to be connected with these characters because in a 3D movie you cannot cut and force the viewer’s attention, you can’t shake him, and you have to let him be there with the characters. Thankfully, we have great actors.”

“The modern movie-going audience is thirsty for something that they haven’t seen before. But they’re not going to care if they’re not connected to the characters going through the experience,” agrees Wills. “First and foremost for us was to really connect this character journey to the audience and then let the experience that they’re having with the aliens, the visual effects, and the 3D inform and complement that, but not to overpower it.”

Views: 160