Wild at Heart movie storyline. Lula’s psychopathic mother goes crazy at the thought of Lula being with Sailor, who just got free from jail. Ignoring Sailor’s probation, they set out for California. However their mother hires a killer to hunt down Sailor. Unaware of this, the two enjoy their journey and themselves being together… until they witness a young woman dying after a car accident – a bad omen.

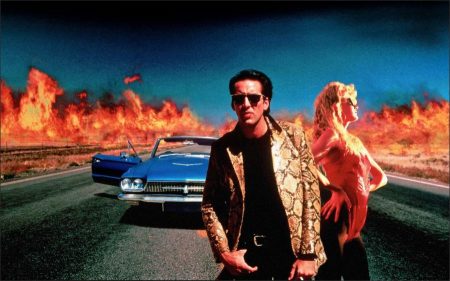

Wild at Heart is a 1990 American film written and directed by David Lynch, and based on Barry Gifford’s 1989 novel of the same name. Both the book and the film revolve around Sailor Ripley and Lula Pace Fortune, a young couple from Cape Fear, North Carolina, who go on the run from her domineering mother and the gangsters she hires to kill Sailor.

Lynch was originally going to produce but after reading Gifford’s book decided, to also write and direct the film. He did not like the ending of the novel and decided to change it in order to fit his vision of the main characters. Wild at Heart is a road movie and includes several allusions to The Wizard of Oz as well as Elvis Presley and his movies.

Film Review for Wild at Heart

Like it or not, David Lynch’s Wild At Heart is a real film. And after a summer of production line movies, dedicated to making money as quickly as possible before being consigned to the waste bin, that’s something to be grateful for. But then we’ve always known, ever since Eraserhead and despite Dune, that Lynch was a talent not to be ignored.

Wild At Heart is essentially Eraserhead made for real money a half in earnest, half joking portrait of America that’s nightmarish in general but realistic in minor detail. It follows Blue Velvet and the television soap Twin Peaks, so its shock value will be less than theirs. But it is every bit as audacious, eccentric and determined to make a mark.

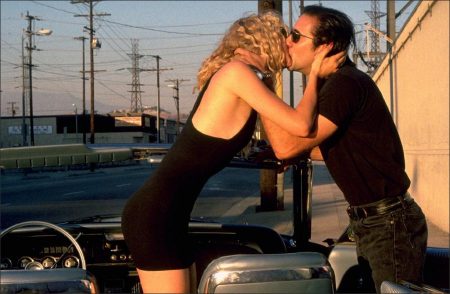

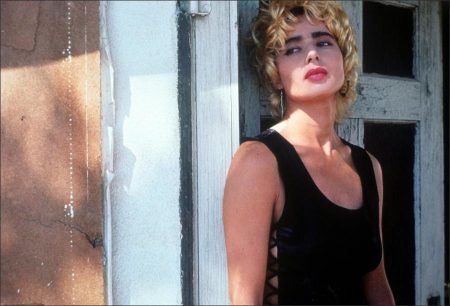

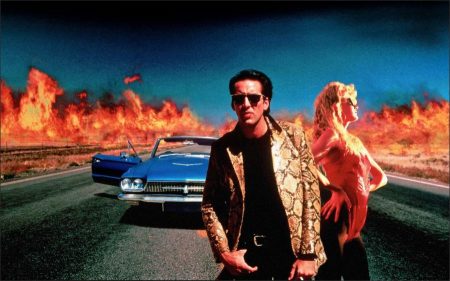

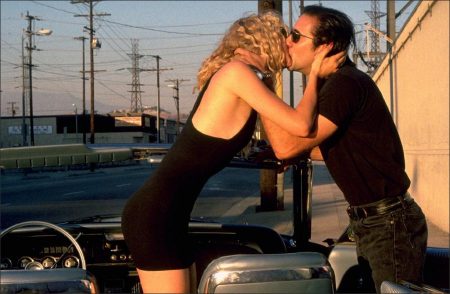

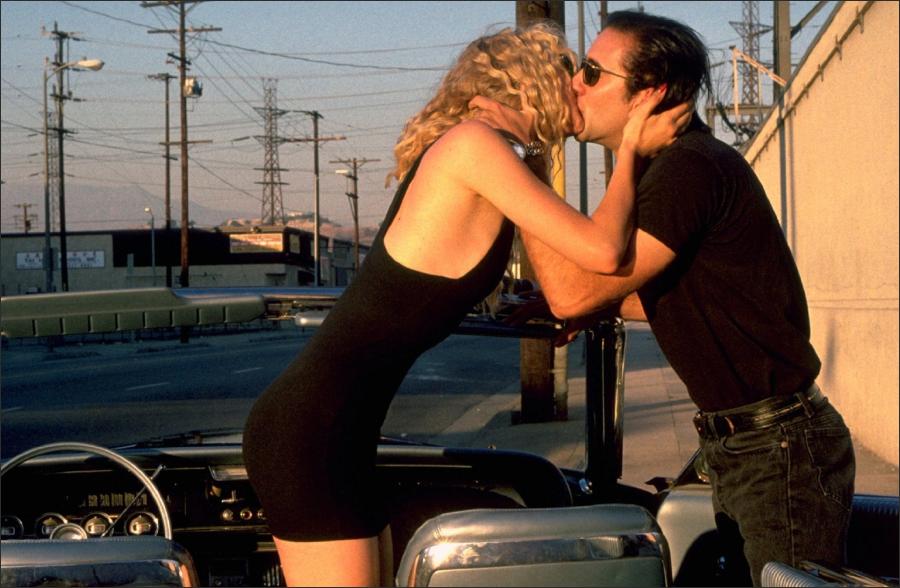

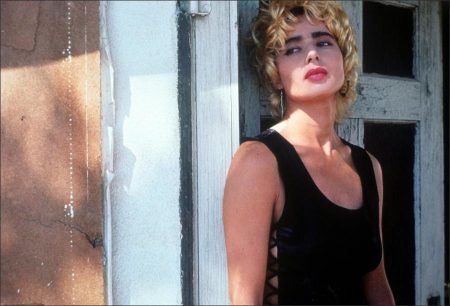

Basically, it’s a road movie and a love story like Bonnie & Clyde, with Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern running across the South, chased by two of her mother’s lovers with murderous intent. He is a sailor just out of prison, a low-life rock and roller who would be a rebel if only he knew what conventional life was all about in the first place. She is a screwed-up teenager, raped at 13 and now reacting against the witch-like angst of a mother who planned her father’s murder and is now determined to protect her in similar bloody fashion. Everyone has a worm in the bud, eating away not just at their happiness but their sanity.

The story is told with an almost cartoon-like ferocity and a virtuoso appreciation of how to make the ordinary seem strange and the strange seem unutterable. Lynch’s camera plunges through sequences as if hell-bent on showing you something you’ve never seen before.

His imagination is likewise able to cause insomnia. Heads explode, dogs run off with severed human hands, and even sex becomes an erotic battleground that could well end in violent disaster. Lynch’s portrait of everyday America is of a culture so ugly and so banal that when something awful happens it is not so much a surprise as perfect logic. If his lovers are slightly crazy, they seem to have every right to be.

But, like Blue Velvet, its criticism is tempered with moments of nostalgia and even affection. Intellectually it is not like Bunuel, since its philosophy is radical only in what we see, not what we feel. But, without Bunuel, it is unlikely that it could have existed.

For an hour, and probably more, Wild At Heart is quite brilliant. After which, I am not sure it feels either that it can progress or that there is any further to go. And it is much weakened by a final section which relapses at crucial points into black jokeness as if to tell us that we needn’t, after all, treat it seriously.

In that way, it is not as good as Blue Velvet. But the surprise element in that film may have been enough to colour our memories in its favour. What you can say about its successor is that its notable vision of a corrupt and decadent society, wild at heart and weird on top, as somebody says, has been refined and in some ways strengthened. Where Lynch goes from here will be very interesting indeed.

His risk taking extends to the performances which have an air of frantic improvisation that lends an urgency to almost all of them. Cage and Dern have never been better and Diane Ladd (Dern ‘s real mother) and Harry Dean Stanton as the love-lorn detective are equally notable, as is Willem Dafoe as a crazed killer. The faces seem part of the nightmare as much as the action.

All one requires from the film for it to seem complete is a less fractured and excitable statement of intent something still and insistent at its centre. But Lynch hasn’t yet learnt that trick. And until he does we can respect him as a brilliant film-maker but not yet as a great one. If he is perfectly capable of churning up our emotions, he cannot yet really move us.

Wild at Heart (1990)

Directed by: David Lynch

Starring: Nicolas Cage, Laura Dern, Willem Dafoe, Crispin Glover, Diane Ladd, Isabella Rossellini, Harry Dean Stanton, Lisa Ann Cabasa, Frances Bay

Screenplay by: David Lynch

Production Design by: Patricia Norris

Cinematography by: Frederick Elmes

Film Editing by: Duwayne Dunham

Costume Design by: Amy Stofsky

Music by: Angelo Badalamenti

Distributed by: The Samuel Goldwyn Company

Release Date: August 17, 1990

Views: 282