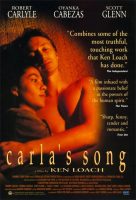

Taglines: A dream called freedom. A nightmare called Nicaragua.

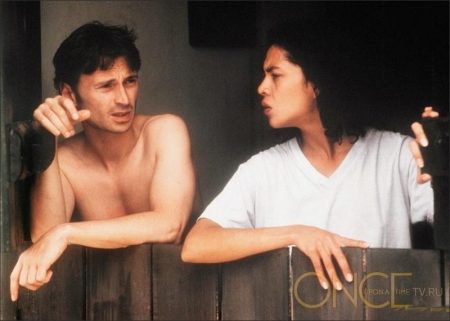

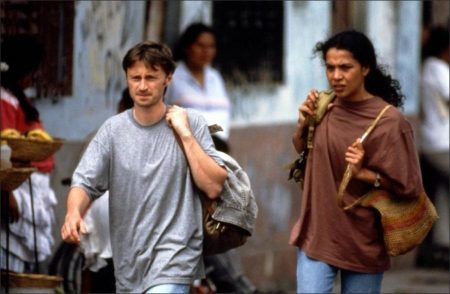

Carla’s Song movie storyline. 1987, love in time of war. A bus driver George Lennox meets Carla, a Nicaraguan exile living a precarious, profoundly sad life in Glasgow. Her back is scarred, her boyfriend missing, her family dispersed; she’s suicidal. George takes her to Nicaragua to find out what has happened to them and to help her face her past.

Once home, Carla’s nightmarish memories take over, and Carla and George are thrown into the thick of the US war against the Sandinistas. A mystery develops over where Carla’s boyfriend is, and the key to his whereabouts may be Carla’s friend Bradley, a bitter American aid worker. She finds her family, the Contras attack, and she and the Scot face their choices.

Carla’s Song is a 1996 British film directed by Ken Loach and written by Paul Laverty. Set in 1987, it tells the story of the relationship between a Scottish bus driver, George Lennox (Robert Carlyle) and Carla (Oyanka Cabezas), a Nicaraguan woman living in exile in Glasgow. Searching for her past (her family and boyfriend), Carla returns to war-torn Nicaragua with George, into the thick of the U.S. sponsored Contra insurgency against the Sandinistas.

Film Review for Carla’s Song

he trouble about writing fiction is that I spend too much time in a room by myself. On occasions I wonder if I’m going nuts, or whether, just maybe, my quiet fury is a normal reaction from an average human being. On Sunday, much to my delight, Universal brought out a new DVD of Carla’s Song, written by me and directed by Ken Loach, set against the backdrop of the US-financed war during the 1980s in Nicaragua, where I once worked for a human-rights organisation.

The team at Universal were genuinely enthusiastic and worked their pants off to pull it all together. Along with the new director’s cut is a glossy booklet with photographs and excerpts from the introduction to my screenplay, written in 1996. I was on a film set when I got word that the text was going to print and I only had 10 minutes to glance over their summary. I faxed a one-paragraph postscript and that is when the trouble started.

Despite the best efforts of the young man at Universal to get my postscript in, he was informed by lawyers that they could not risk it. My agent received a phone call from a lawyer saying what I had written was deemed to be “contentious and inflammatory”. I asked for a copy of the opinion but was told that it was “verbal”. I asked who counsel was, and on what basis they reached their opinion. Not a squeak. Deadline passed. Postscript gone.

Here is the offending paragraph: “The man who was at the centre of the US experiment to tear Nicaragua apart in the 80s was Mr John Negroponte, once US ambassador to Honduras. He claims to be unaware of any US human rights abuse in Nicaragua or El Salvador during this time. In January of 2005 he was appointed head of national intelligence by George Bush Jnr. Each morning he should have no difficulty spotting a terrorist.”

Although many continue to question how much Negroponte knew during his time in Honduras, his political rehabilitation has been marked. Last year, he was given the testing position of US ambassador to Iraq, making him head of the biggest diplomatic staff in the world.

Advertisement

David Corn, a US journalist, wrote in detail about Negroponte: “While he was in Honduras and for years afterwards, Negroponte refused to acknowledge the human rights abuses. In a letter to the Economist he said it was ‘simply untrue to state that death squads have made their appearance in Honduras’.”

Corn asks him to account therefore for a CIA report that states: “The Honduran military committed hundreds of human rights abuses since 1980, many of which were politically motivated and officially sanctioned” and linked to “death squad activities”. He also quotes from a Baltimore Sun series from 1995: “Time and time again… Negroponte was confronted by evidence that a Honduran army intelligence unit, trained by the CIA, was stalking, kidnapping, torturing and killing suspected subversives.”

Honduras was bribed and bullied by the US to host the Contras, who were fighting the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. Negroponte, as ambassador, was the local cheerleader taking his instructions from Washington. Every serious human rights organisation conducted detailed investigations within Nicaragua at this time, and while the Sandinistas came in for some heavy criticism too, all revealed widespread and systematic abuse by the Contras, much of it directed at civilians.

Two memories still haunt me. We got a report one night of a Contra attack on a cooperative. In the chaos, a young woman was shot and couldn’t run. Her parents somehow got away to the safety of a trench, only to hear the Contras in the near distance torturing their daughter. They found her dead in the ditch the next day with her breasts cut off. Incidents like this peppered the entire war.

I also interviewed a young Contra who had been captured by the Sandinistas. He told me he had been involved in many ambushes. While staring out of the window he drifted off into a terrifying reverie and with an imaginary knife in hand, he swished it back and forth, describing how he finished off those lying wounded from an ambushed vehicle.

Almost 20 years on, his face keeps coming back to mind. So too does the image of Negroponte in his new office at national intelligence, in charge of 15 agencies with a multi-billion-dollar budget to seek out terrorists around the world. I’m sure they never met, and suspect the former’s butchery would be roundly condemned in diplo-speak by the latter. Can I ask the outrageous question: “What is the difference between those two men?”

One has no name and is long forgotten, one of many thousands of illiterate campesino teenagers who did the dirty work on flesh with knives, and wreaked havoc on themselves and their neighbours. The other is a highly trained Yale graduate, a polyglot promoted by Kissinger after he learned Vietnamese, who went on to be US ambassador to the UN, Iraq, and now head of national intelligence, whose only weapon is a pen and a microphone. Kofi Annan, in the UN headquarters, called him “a great diplomat and a wonderful ambassador”. So who am I in my tiny room to call Negroponte a human rights denier, and a champion of teenage mutilators?

I am reminded of that wonderful perception by the American philosopher John Dewey who once said: “If you want to establish some conception of a society, go find out who is in gaol.” Perhaps, in these times, it should be updated by adding “…and who obtains high office.”

In my fantasy, I imagine the ghost of Peter Benenson, the founder of Amnesty, turning in his grave at the CIA kidnapping their terror suspects in Europe and dumping them in client states for vicarious torture; new US attorney general Alberto Gonzales advising Bush that some elements of the Geneva conventions are “obsolete”; US general Ricardo Sanchez’s memo authorising new interrogation techniques that violate the Geneva conventions; subcontracting of interrogation by private US contractors in Iraq; and UK ambassador Craig Murray, fired from his post in Uzbekistan for “operational reasons”, who coincidentally took up the case of a mother whose son was boiled alive in detention, and who further claimed MI6 had used information gained by torture passed on by the CIA. Torturers are on the march; some have muscle and plastic gloves, others have expensive educations to chip away at legal convention, and most insidious of all, the wordsmiths, who “soften up” public opinion with “sleep manipulation”.

In my continuing dream, Peter Benenson comes back from the grave carrying a little symbol of the scales of justice wrapped up in barbed wire, with a Milan Kundera quote underneath: “The struggle against power is the struggle against forgetting.” He calls on us to set up a sister organisation to Amnesty, perhaps Memory International, one that uses the power of public opinion and ordinary decency, not just to follow the fate of the prisoner, but to monitor and challenge the other side of the equation: not the abused, but the “abuser”, whether that be the head of the detention centre, the manufacturer who sells the electric batons or, most important of all, their political champions in high office who make their dirty work possible, but never mess their own suit.

Negroponte told his critics last year that allegations against him were “old hat”. He said: “I want to say to those people: haven’t you moved on?” Not an inch, Mr National Intelligence Director. I remember.

Carla’s Song (1997)

Directed by: Ken Loach

Starring: Robert Carlyle, Oyanka Cabezas, Scott Glenn, Salvador Espinoza, Louise Goodall, Subash Singh Pall, Margaret McAdam, Pamela Turner, Anne Marie Timoney

Screenplay by: Paul Laverty

Production Design by: Martin Johnson

Cinematography by: Barry Ackroyd

Film Editing by: onathan Morris

Costume Design by: Daphne Dare, Lena Mossum

Art Direction by: Fergus Clegg, Llorenç Miquel

Music by: George Fenton

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Release Date: January 31, 1997

Views: 237