Evita allows the audience to identify with a heroine who achieves greatness by–well, golly, by being who she is. It celebrates the life of a woman who begins as a quasi-prostitute, marries a powerful man, locks him out of her bedroom, and inspires the idolatry of the masses by spending enormous sums on herself. When she sings: “They need to adore me–to Christian Dior me,” she’s right on the money.

I begin on this note not to criticize the new musical “Evita” (which I enjoyed very much), but to bring a touch of reality to the character of Eva Peron, who, essentially, was famous because she was so very well-known. Her fame continued after her death, as her skillfully embalmed body went on to a long-running career of its own, displayed before multitudes, spirited to Europe, fought over, prayed over, and finally sealed beneath slabs of steel in an Argentine cemetery. Eva Peron lived only until 33, but she went out with a long curtain call.

She was not an obvious subject for a musical. Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice, who wrote the stage version of “Evita” and whose songs are wall-to-wall in the movie, must have known that; why else did they provide a key character named Che Guevera (onstage) and Che (on screen), to ask embarrassing questions? “You let down your people, Evita,” he sings. She let down the poor, shirtless ones by providing a glamorous facade for a fascist dictatorship, by salting away charity funds, and by distracting from her husband’s tacit protection of Nazi war criminals.

Why, then, were Webber and Rice so right in choosing Eva Peron as their heroine? My guess is that they perfectly anticipated “Evita’s” core audience–affluent, middle-aged and female. The musical celebrates Eva Peron’s narcissism, her furs and diamonds, her firm management of her man. Given such enticements, what audience is going to quibble about ideology? For years I have wondered, during “Don’t Cry for Me, Argentina,” why we were not to cry. Now I understand: We need not cry because (a) Evita got everything out of life she dreamed of, and (b) Argentina should cry for itself. Even poor Juan Peron should shed a tear or two; he is relegated in the movie to the status of a “walker,” a presentable man who adorns the arm of a rich and powerful woman as a human fashion accessory.

All of these thoughts, as I watched Alan Parker’s “Evita,” did not in the least prevent me from having a good time. I suspect Parker has as many questions about his heroine as I do, and I am sure that Che (Antonio Banderas) and Juan Peron (Jonathan Pryce) do–not to mention Oliver Stone, co-author of the screenplay. Only Evita herself, magnificently embodied by Madonna, rises above the quibbles, as she should; if there is one thing a great Evita should lack, it is any trace of self-doubt. Here we have a celebration of a legendary woman (for those who take the film superficially) and a moral tale of a misspent life (for those who see more clearly).

Certainly Parker is a good director for this material. He has made more musicals than his contemporaries, not only “Bugsy Malone,” “Fame” and “The Commitments,” but especially “Pink Floyd the Wall,” one of the great modern musicals, where he uses similar images of marching automatons. Working with exteriors in Argentina and Hungary and richly detailed interior sets, he stages Evita’s life as a soap opera version of “Triumph of the Will,” with goose-stepping troops beating out the cadence of her rise to glory.

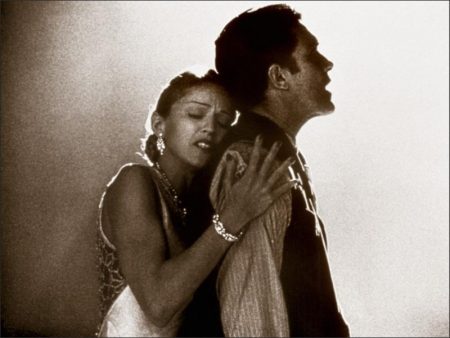

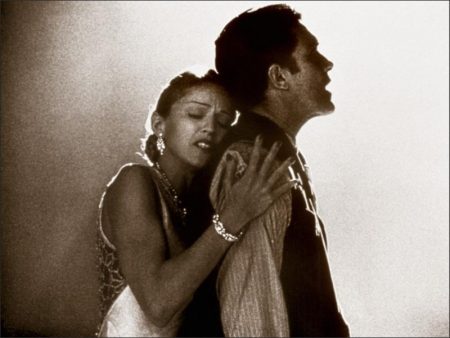

The movie is almost entirely music; the fugitive lines of spoken dialogue sound sheepish. Madonna, who took voice lessons to extend her range, easily masters the musical material. As importantly, she is convincing as Evita–from the painful early scene where, as an unacknowledged child, she tries to force entry into her father’s funeral, to later scenes where the poor rural girl converts herself into a nightclub singer, radio star, desirable mistress, and political leader.

There is a certain opaque quality in Madonna’s Evita; what you see is not exactly what you get. The Che character zeroes in on this, questioning her motives, doubting her ideals, pointing out contradictions and evasions. Yet for Evita there are no inconsistencies, because everything she does is at the service of her image. It is only if you believe she is at the service of the poor that you begin to wonder.

Listen closely as she sings: “For I am ordinary, unimportant And undeserving Of such attention Unless we all are I think we all are So share my glory.” The poor, in other words, deserve what Evita has, so her program consists of her having it and the poor being happy for her. After all, if she didn’t have it, she’d be poor, too. In other words: The lottery is wonderful, just as long as I win it.

Banderas, as Che, sees through this; his performance is one of the triumphs of the movie. He sings well, he has a commanding screen presence, and he finds a middle ground between condemnation and giving the devil her due. He is “of the people” enough to feel their passion for Evita, and enough of a revolutionary to distrust his feelings.

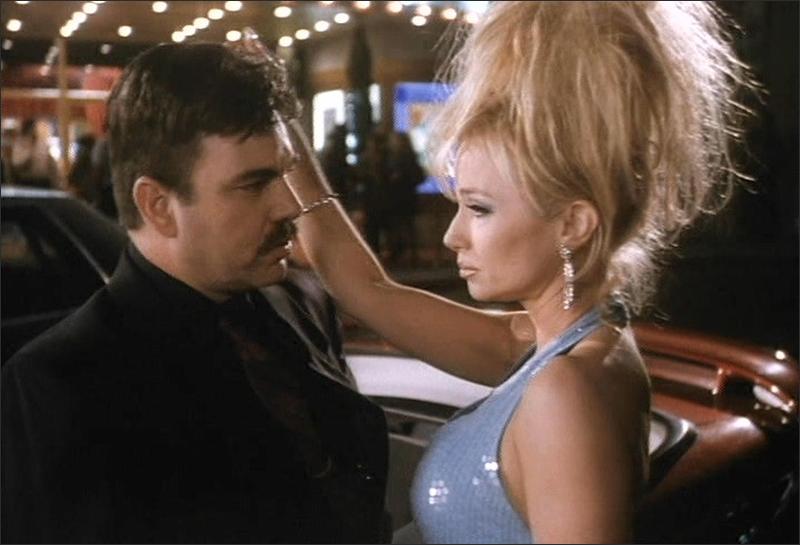

Pryce, as the dictator, remains more difficult to read. He is grateful for the success Evita brings him (her broadcasts free him from prison, her campaigns win his elections, her fame legitimatizes his regime). But there is a quiet little scene where he knocks on her locked bedroom door and then shuffles back to his own room, and that scene speaks volumes for the haunted look in his eyes.

The music, like most of the Webber/Rice scores, is repetitive to the point of brainwashing. It’s as if they come up with one good song and go directly into rehearsals. The reason their songs become hits is that you’ve heard them a dozen times by the end of the show. But Parker’s visuals enliven the music, and Madonna and Banderas bring it passion. By the end of the film we feel like we’ve had our money’s worth, and we’re sure Evita has.

Evita (1996)

Directed by: Alan Parker

Starring: Madonna, Antonio Banderas, Jonathan Pryce, Jimmy Nail, Victoria Sus, Julian Littman, Olga Merediz, Laura Pallas, Julia Worsley, María Luján Hidalgo

Screenplay by: Alan Parker, Oliver Stone

Production Design by: Brian Morris

Cinematography by: Darius Khondji

Film Editing by: Gerry Hambling

Costume Design by: Penny Rose

Set Decoration by: Philippe Turlure

Art Direction by: Richard Earl, Jean-Michel Hugon

Music by: Andrew Lloyd Webber

MPAA Rating: PG for thematic elements, images of violence and some mild language.

Distributed by: Buena Vista Pictures

Release Date: December 25, 1996

Views: 370