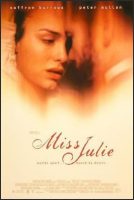

Taglines: Worlds apart… bound by desire.

Miss Julie movie storyline. Midsummer night, 1894, in northern Sweden. The complex strictures of class bind a man and a woman. Miss Julie, the inexperienced but imperious daughter of the manor, deigns to dance at the servant’s party. She’s also drawn to Jean, a footman who has traveled, speaks well, and doesn’t kowtow.

He is engaged to Christine, a servant, and while she sleeps, Jean and Miss Julie talk through the night in the kitchen. For part of the night it’s a power struggle, for part it’s the bearing of souls, and by dawn, they want to break the chains of class and leave Sweden together. When Christine wakes and goes off to church, Jean and Miss Julie have their own decisions to make.

Miss Julie is a 1999 film directed by Mike Figgis based on the play of the same name by August Strindberg, starring Saffron Burrows in the role of Miss Julie and Peter Mullan in the role of Jean. Other starring are Miss Julie, Miss Julie 1999, Maria Doyle Kennedy, Tam Dean Burn, Heathcote Williams, Eileen Walsh, Sue Maund, Joanna Page, Andrea Ollson, and Sara Li Gustafsson.

Film Review for Miss julie

August Strindberg felt that the entire world had gone crazy. The “norms” of class hierarchies and gender roles were starting to shatter, and he saw chaos pouring into that vacuum. His 1888 play “Miss Julie” is the prime example, although it’s evident in all of his other disturbing, great modern works.

“Miss Julie” plays in almost real-time, taking place in one setting over the course of a single evening, Midsummer Night’s Eve, the one long night of the year when the classes blend together, when rich dance and drink with poor, when the boundaries have blurred. There are only three characters in the play, and it opens with Jean, an upwardly-striving valet remarking to his pal and sort-of girlfriend, the kitchen maid, that “Miss Julie is crazy!” Miss Julie is the daughter of the count in whose manor they both work.

Strindberg was a nervous man, whose plays read like frenziedly-written journal entries of despair and anxiety (crying out, like Dr. Venkman in “Ghostbusters,” “Human sacrifice, dogs and cats living together, mass hysteria!”) Legendary acting teacher Stella Adler lectured extensively on Strindberg (and other playwrights), and these lectures have been published in a wonderful volume, “Stella Adler on Ibsen, Strindberg, and Chekhov.”

Adler spoke of the difference between Ibsen and Strindberg, helpful to keep in mind when examining Strindberg: “In Ibsen, the single person is rebellious. In Strindberg, you can’t really rebel. In Ibsen, you don’t break the social form. In Strindberg, the social pattern of life is broken. The revolt is a strong, nervous one. It doesn’t come through as ideas but as temperament – violent. Inner conflict with Ibsen leads to ideas; with Strindberg it leads to chaos.”

When Liv Ullmann’s “Miss Julie” works best, it shows us that total emotional and social chaos, chaos that destroys not only the individual characters in the play, but the entire society in which they live. “Miss Julie” is a rather strange experience, with its consistently static medium shots of the three actors, as they roar their lines at one another. But it has an undeniable power. For Strindberg to work, one must feel the context of his time, and understand Miss Julie’s immediate ruination by “falling” for the valet (the script is filled with images of rising and falling).

Ullmann’s adaptation of Strindberg’s script stays very close to the original; the main change being that it now takes place on an estate in Ireland. Ullmann opens up the action only slightly, with the reveling Midsummer Night’s Eve crowds always offstage, heard but never seen. There are a couple of scenes in Jean’s bedroom, and one outdoor scene when Jean and Miss Julie take a walk. Other than that, the action stays in the kitchen, suggesting how much Miss Julie is “lowering” herself by hanging out there. The claustrophobia of the kitchen is overwhelming in the film, and the shots of Miss Julie wandering through the manor by herself, her posture broken and stiff, her dress falling off her shoulder, give us a welcome (and yet rivetingly disturbing) change of scene.

The three characters are played by Jessica Chastain, Colin Farrell and Samantha Morton, and each actor has to deliver some of the most challenging monologues ever written, with no cinematic tricks. Many of the monologues are delivered wholesale, in one shot, with barely a cut-away to the listener. It requires A-game acting, shots like that, and watching these actors work is the main pleasure of “Miss Julie.” Ullmann doesn’t worry too much about making the action cinematic, and the constant monologuing can get a little trying. The entire play is conversation, bantering at first, growing in desperation, until finally the chaos roars in like a tsunami.

As Miss Julie breaks down, Chastain is, quite frankly, extraordinary. She gathers her considerable powers and pours them into a role that is different from anything else she has ever done. It’s a powerhouse performance, without any self-congratulatory or self-indulgent giveaways. Her agony is so palpable that one wonders how she will survive her own performance. Feeling that way is essential for “Miss Julie” to work, and from Chastain’s unforgettable first entrance, sidling into the kitchen, looking like a wreck, the crack in her psyche is already clearly visible on her face.

Farrell is terrific as Jean, playing around with Miss Julie at first, following her seemingly heedless orders to kiss her shoe, despite what it might look like to others, and despite the fact that he is in a relationship with Kathleen. He warns her at one point that by flirting with him, she is playing with fire.

He’s not to be trifled with. He is a man trapped in his social station, although he is representative of the movement between the classes, a valet who has traveled the world with his Master, knows about good wines (although he steals a bottle on occasion), speaks other languages, and has an ease in the world that Miss Julie lacks.

And yet when the Master rings the bell for him, his loyalty sways automatically towards the man he serves. He is in deep conflict, and the fact that Miss Julie falls so hard for him shows that she is just as “low” as he is. His lust turns to contempt in a devastating heartbeat. Farrell manages all of this gracefully and sensitively, as though he were born to play the role. It’s a great fit.

And Samantha Morton as Kathleen, the maid, is horrified and betrayed by Miss Julie’s inappropriate bantering going on in her kitchen with her man. Unlike the other two characters, Kathleen knows her place, and respects those “above” her. The movement between the classes, representative by Jean and Miss Julie’s one-night fling, fills her with disgust and apprehension. She’s Strindberg’s stand-in. Morton is magnificent.

Some of her best moments are reaction shots. As Miss Julie babbles to her about how she and Jean are going to set up a hotel on Lake Como, and maybe Kathleen can work in the kitchen there, and marry a nice man eventually, Morton’s face shows the deep horror of not only what she is seeing, but the clear madness in Chastain’s performance. “Do you really believe all that, Miss Julie?” she breathes. “Miss Julie” is filled with small moments like that, small behavioral moments that are rich and strange, trembling with possibility and terror.

Miss Julie was raised with massive financial advantages, but she was also raised in total chaos. There is madness in her family line. Her mother taught her to hate men. That is the crux of Miss Julie’s problem, and that is the destabilizing effect that Jean, the good-looking valet, has on her. When she “falls” for him, she means it. But the second they sleep together, Jean turns on her. She’s a whore to him now.

After Jean and Miss Julie sleep together, Chastain sits in his bed, stiff and traumatized, wiping the blood from between her legs, with plucking frozen fingers, the panic trembling off of her posture. (“Miss Julie” also, famously, has her period, mentioned in the first scene by Kathleen, who uses it as a possible explanation for why Miss Julie’s behavior has been so “queer” in the couple of days prior.) With all of the monologuing in the film, Chastain’s body language in that scene, and directly afterwards, as she walks away from Jean’s room, in pain and entirely altered, tells the story clearer than any words could do.

Ullmann fills the score with mournful Schubert and Bach, familiar pieces of music that become thematic, as opposed to mere pretty background. The scenes of Miss Julie by herself, trapped in her red bedroom with her caged finch, or staggering drunk up the main stairway of the manor, a ruined woman, running from the madness of what she has done, are made even more powerful by that urgent insistent underscoring.

Reaction to the film will depend on how one feels about seeing three people stand around delivering lines at one another. But the acting is so good it creates its own mood, outside of anything cinematic that Ullmann could have chosen to add to it; it creates its own atmosphere of claustrophobia, hysteria, and self-loathing. Ullmann, a brilliant actress herself, hands the script over to her actors. It is theirs.

Miss Julie (1999)

Directed by: Mike Figgis

Starring: Saffron Burrows, Peter Mullan, Maria Doyle Kennedy, Tam Dean Burn, Heathcote Williams, Eileen Walsh, Sue Maund, Joanna Page, Andrea Ollson, Sara Li Gustafsson

Screenplay by: Helen Cooper

Production Design by: Michael Howells

Cinematography by: Benoît Delhomme

Film Editing by: Matthew Wood

Costume Design by: Sandy Powell

Set Decoration by: Totty Lowther

Art Direction by: Philip Robinson

Music by: Mike Figgis

MPAA Rating: R for language and a scene of sexuality.

Distributed by: Metro Goldwyn Mayer

Release Date: December 10, 1999

Views: 282