The Loss of Sexual Innocence movie storyline. Director Mike Figgis, creator of the Academy award-winning Leaving Las Vegas, presented this film’s world premiere at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival. The story is made up of non-linear, interconnected episodes about a man at different stages of his life, all of which explicate thematically the film’s title. The film also juxtaposes a retelling of the classic biblical fall-from-grace tale of Adam and Eve.

We see the leading character, Nic, at 5 years old as a boy in colonial Kenya, at age 16 in swinging London in the ’60s, and as a grown man working as a film ethnographer. Each sequence shows how he lost some degree of his sexual innocence, whether it be through love, puberty, or masturbation. Shot all over the world, including Tunisia, Italy, and England, the film is an exploration of sex and loss through the life of one individual.

The Loss of Sexual Innocence is a 1999 film written and directed by Mike Figgis. It tells the story of the sexual development of a filmmaker through three stages of his life, in a non-linear and disjointed manner. The film stars British actress Saffron Burrows, whom Figgis dated for several years.

Film Review for The Loss of Sexual Innocence

Mike Figgis, who pays so much attention to the music in his films, has made one that plays like a musical composition, with themes drifting in and out, and dialogue used more for tone than speech. “The Loss of Sexual Innocence” is built of memory and dreams, following a boy named Nic as he grows from a child into a man, and intercutting his story with the story of Adam and Eve. Not all of it works, but you play along, because it’s rare to find a film this ambitious.

Figgis knows how to tell a story with dialogue and characters (“Leaving Las Vegas” is his masterpiece), but here he deals with impressions, secrets, desires. His story is about the way the world breaks our own Gardens of Eden, chopping down the trees and divesting us of our illusions. The process begins early for Nic, a British boy being reared in Kenya in 1953, when through a slit in a window he observes an old white man watching while a young African girl, dressed only in lingerie, reads to him from the Bible.

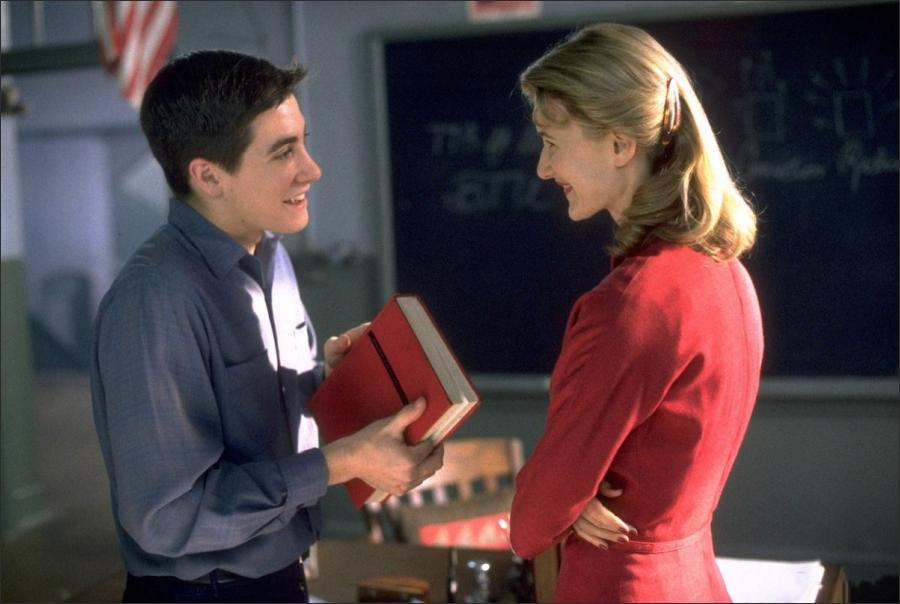

We move forward 10 years or so, to England, where Nic, now 16 or so, is ignored by his girlfriend Susan at a family function. Susan gets drunk, and Nic discovers her upstairs, necking with an older man on the bed. Later there is a scene from their courtship, when Nic and Susan are younger and they steal into her house at night. She makes him coffee, they kiss by the fire, and then her father enters. He doesn’t “catch” them and hardly notices them; he is in pain, and takes pills. Their young love is contrasted with the end that awaits us all.

These episodes are intercut with “Scenes From Nature,” as Adam and Eve (Femi Ogumbanjo and Hanne Klintoe) emerge from a pond and explore the world, and their own bodies, with amazement. The nudity here, while explicit, is theologically correct; we didn’t need clothing until we sinned. The whole Eden sequence could have been dispatched with, I think. (Its surprise payoff tries too hard to make a point that the ending of “Walkabout” made years ago.)

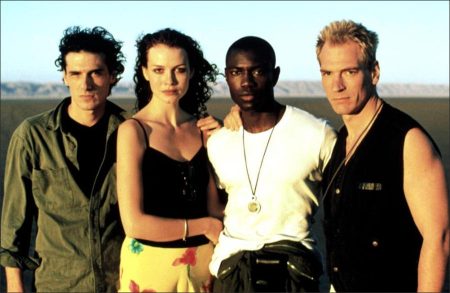

Yet the Eden scenes are so beautifully photographed that you enjoy them even as you question them. (The first shot of Eden is a breathtaking optical illusion.) Nic’s story, as it unfolds, reveals unhappiness. As he becomes an adult, now played by Julian Sands, we see glimpses of a marriage underlined with tension. He is a film director, and there is a trip to Tunisia that ends with a surprise development that is a sudden, crushing loss of innocence. And Figgis also weaves on a strand involving twins (played by Saffron Burrows) who are separated shortly after birth, and come face to face with each other in an airport years later. To look at your own face on another person is a fundamental loss of innocence, because it deprives you of the assumption that you are unique.

The film has no particular statement to make about its material (apart from the symbolism of the Eden sequence). It wants to share feelings, not thoughts. A lot of the dialogue sounds remembered, or overheard from a distance (I was reminded of the dialogue treatment in “Bonnie and Clyde” when Bonnie goes to a family picnic and talks with her mother). We get the points that are being made, but this movie isn’t about people talking to one another.

The film itself moves forward, but there are flashbacks of memory, as Nic, driving, recalls scenes from earlier life. There are two dream sequences–one for him, one for his wife, played by Johanna Torrel. Hers is about his indifference as he plays the piano while she makes love with another man. His is about his own death. We don’t know if this material comes from Mike Figgis’ life, but we’re sure it comes from his feelings.

“The Loss of Sexual Innocence” is an “art film,” which means it tries to do something more advanced than most commercial films (which tell stories simple enough for children, in images shocking enough for adults). It wants us to share in the process of memory, especially sexual memory. It assumes that the moments we remember most clearly are those when we lost our illusions–when we discovered the unforgiving and indifferent nature of the world. It’s like drifting for a time in the film’s musings, and then being invited to take another look at our own.

The Loss of Sexual Innocence (1999)

Directed by: Mike Figgis

Starring: Julian Sands, Saffron Burrows, Stefano Dionisi, Kelly Macdonald, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Gina McKee, Bernard Hill, Rossy de Palma, Nina McKay, Femi Ogunbanjo

Screenplay by: Mike Figgis

Production Design by: Giorgio Desideri

Cinematography by: Benoît Delhomme

Film Editing by: Matthew Wood

Costume Design by: Florence Nicaise

Music by: Mike Figgis

MPAA Rating: R for strong sexual images, pervasive nudity, violence and language.

Distributed by: Sony Pictures Classics

Release Date: May 28, 1999

Views: 697