The Piano is as peculiar and haunting as any film I’ve seen. It tells a story of love and fierce pride, and places it on a bleak New Zealand coast where people live rudely in the rain and mud, struggling to maintain the appearance of the European society they’ve left behind. It is a story of shyness, repression and loneliness; of a woman who will not speak and a man who cannot listen, and of a willful little girl who causes mischief and pretends she didn’t mean to.

The film opens with the arrival of a 30ish woman named Ada (Holly Hunter) and her young daughter, Flora (Anna Paquin), on a stormy gray beach. They have been rowed ashore, along with Ada’s piano, to meet a local bachelor named Stewart (Sam Neill), who has arranged to marry her. “I have not spoken since I was 6 years old,” Ada’s voice tells us on the soundtrack. “Nobody knows why, least of all myself. This is not the sound of my voice; it is the sound of my mind.” Ada communicates with the world through her piano, and through sign language, which is interpreted by her daughter.

Stewart and his laborers, local Maori tribesmen, take one look at the piano crate and decide it is too much trouble to carry inland to the house, and so it stays there, on the beach, in the wind and rain. It says something that Stewart cares so little for his new bride that he does not want her to have the piano she has brought all the way from Scotland – even though it is her means of communication. He does not mind quiet women, is one way he puts it.

Ada and Flora settle in. No intimacy grows between Ada and her new husband. One day she goes down to the beach to play the piano, and the music is heard by Baines (Harvey Keitel), a roughhewn neighbor who has affected Maori tattoos on his face. He is a former whaler who lives alone, and he likes the music of the piano – so much that he trades Stewart land for the piano.

“That is MY piano – MINE!!” Ada scribbles on a note she hands to Stewart. He explains that they all make sacrifices and she must learn to, as well. Baines invites her over to play, and thus begins his singleminded seduction, as he offers to trade her the piano for intimacy. There are 88 keys. He’ll give her one for taking off her jacket. Five for raising her skirt.

Jane Campion, who wrote and directed “The Piano,” does not handle this situation as a man might. She understands better the eroticism of slowness and restraint, and the power that Ada gains by pretending to care nothing for Baines. The outcome of her story is much more subtle and surprising than Baines’ crude original offer might predict.

Campion has never made an uninteresting or unchallenging film (her credits include “Sweetie,” about a family ruled by a self-destructive sister, and “An Angel at My Table” (the autobiography of writer Janet Frame, wrongly confined for schizophrenia). Her original screenplay for “The Piano” has elements of the Gothic in it, of that Victorian sensibility that masks eroticism with fear, mystery and exotic places. It also gives us a heroine who is a genuine piece of work; Ada is not a victim here, but a woman who reads a situation and responds to it.

The performances are as original as the characters. Hunter’s Ada is pale, grim and hatchetfaced at first, although she is capable of warming. Keitel’s Baines is not what he first seems, but has unexpected reserves of tenderness and imagination. Neill’s taciturn husband conceals a universe of fear and sadness behind his clouded eyes. And the performance by Paquin, as the daughter, is one of the most extraordinary examples of a child’s acting in movie history. She probably has more lines than anyone else in the film, and is as complex, too – able to invent lies without stopping for a breath, and filled with enough anger of her own that she tattles just to see what will happen.

Stuart Dryburgh’s cinematography is not simply suited to the story, but enhances it. Look at his cold grays and browns as he paints the desolate coast, and then the warm interiors that glow when they are finally needed. And if you are oddly affected by a key shot just before the end (I will not reveal it), reflect on his strategy of shooting and printing it, not in real time, but by filming at quarter-time and then printing each frame four times, so that the movement takes on a fated, dreamlike quality.

“The Piano” is a movie people have been talking about ever since it first played at Cannes, last May, and shared the grand prix. It is one of those rare movies that is not just about a story, or some characters, but about a whole universe of feeling – of how people can be shut off from each other, lonely and afraid, about how help can come from unexpected sources, and about how you’ll never know if you never ask. The new 1994 edition of Roger Ebert’s Video Companion is now in bookstores.

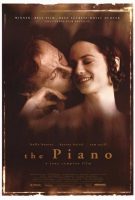

The Piano (1994)

Directed by: Jane Campion

Starring: Holly Hunter, Harvey Keitel, Sam Neill, Anna Paquin, Kerry Walker, Geneviève Lemon, Tungia Baker, Peter Dennett, Pete Smith, Carla Rupuha, Mahina Tunui

Screenplay by: Jane Campion

Production Design by: Andrew McAlpine

Cinematography by: Stuart Dryburgh

Film Editing by: Veronika Jenet

Costume Design by: Janet Patterson

Set Decoration by: Meryl Cronin

Art Direction by: Gregory P. Keen

Music by: Michael Nyman

MPAA Rating: R for moments of extremely graphic sexuality.

Distributed by: Miramax Films

Release Date: February 11, 1994

Views: 191