Thelma and Louise is in the expansive, visionary tradition of the American road picture. It celebrates the myth of two carefree souls piling into a 1956 T-Bird and driving out of town to have some fun and raise some hell. We know the road better than that, however, and we know the toll it exacts: Before their journey is done, these characters with have undergone a rite of passage, and will have discovered themselves.

What sets “Thelma & Louise” aside from the great central tradition of the road picture — a tradition roomy enough to accommodate “Easy Rider,” “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Badlands,” “Midnight Run” and “Rain Man” — is that the heroes are women this time: Working-class girlfriends from a small Arkansas town, one a waitress, the other a housewife, both probably ready to describe themselves as utterly ordinary, both containing unexpected resources.

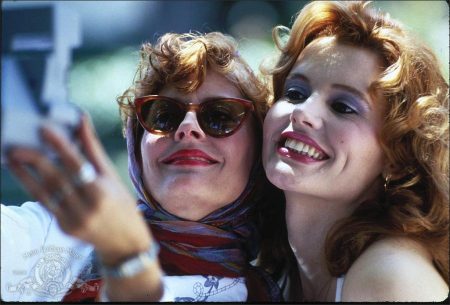

We meet them on days that help to explain why they’d like to get away for the weekend. Thelma (Geena Davis) is married to a man puffed up with self-importance as the district sales manager of a rug company. He sees his wife as a lower order of life, to be tolerated so long as she keeps her household duties straight and is patient with his tantrums. Louise (Susan Sarandon) waits tables in a coffee shop and is involved with a musician who is never ever going to be ready to settle down, no matter how much she kids herself.

So the girls hit the road for a weekend (Thelma is so frightened of her husband she leaves him a note rather than tell him). They’re almost looking to get into trouble, in a way; they wind up in a saloon not too many miles down the road, and Thelma, a wild woman after a couple of margueritas, begins to get caught up in lust after a couple of dances with an urban cowboy.

That leads, as such flirtations sometimes tragically do, to an attempted rape in the parking lot. And after Louise comes to her friend’s rescue, there is a sudden, violent event that ends with the man’s death. And the two women hit the road for real. They are convinced that no one would ever believe their story — that the only answer for them is to run, and to hide.

Now comes what in a more ordinary picture would be the predictable stuff: The car running down lonely country roads in front of a blood-red sunset, that kind of thing, with a lot of country music on the soundtrack. “Thelma & Louise” does indeed contain its share of rural visual extravaganza and lost railroad blues, but it has a heart, too. Sarandon and Davis find in Callie Khouri’s script the materials for two plausible, convincing, lovable characters. And as actors they work together like a high-wire team, walking across even the most hazardous scenes without putting a foot wrong.

They have adventures along the way, some sweet, some tragic, including a meeting with a shifty but sexy young man named J.D. (Brad Pitt), who is able, like the dead saloon cowboy, to exploit Thelma’s sexual hungers, left untouched by the rug salesman. They also meet old men with deep lines on their faces, and harbingers of doom, and state troopers, and all the other inhabitants of the road.

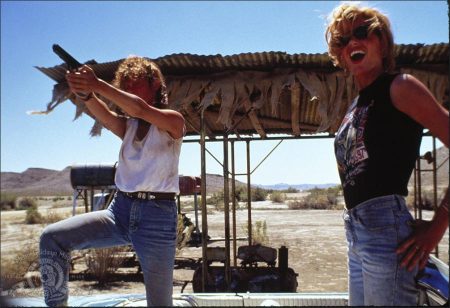

Of course they become the targets of a manhunt. Of course every cop in a six-state area would like to bag them. But back home in Arkansas there’s one cop (Harvey Keitel) who has empathy for them, who sees how they dug themselves into this hole and are now about to get buried in it. He tries to reason with them. To “keep the situation from snowballing.” But it takes on a peculiar momentum of its own, especially as Thelma and Louise begin to grow intoxicated with the scent of their own freedom — and with the discovery that they possess undreamed-of resources and capabilities.

“Thelma & Louise” was directed by Ridley Scott, from Britain, whose previous credits (“Blade Runner,” “Black Rain,” “Legend”) show complete technical mastery but are sometimes not very interested in psychological questions. This film shows a great sympathy for human comedy, however, and it’s intriguing the way he helps us to understand what’s going on inside the hearts of these two women — why they need to do what they do.

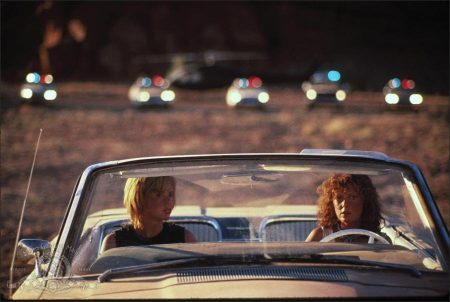

I would have rated the movie at four stars, instead of three and a half, except for one shot, the last shot before the titles begin. This is the catharsis shot, the payoff, the moment when Thelma and Louise arrive at the truth that their whole journey has been pointed toward, and Scott and his editor, Thom Noble, botch it. It’s a freeze frame that fades to white, which is fine, except it does so with unseemly haste, followed immediately by a vulgar carnival of distractions: flashbacks to the jolly faces of the two women, the roll of the end credits, an upbeat country song.

It’s unsettling to get involved in a movie that takes 128 minutes to bring you to a payoff that the filmmakers seem to fear. If Scott and Mount had let the last shot run an additional seven to ten seconds, and then held the fade to white for a decent interval, they would have gotten the payoff they deserved. Can one shot make that big of a difference? This one does.

Thelma and Louise (1991)

Directed by: Ridley Scott

Starring: Susan Sarandon, Geena Davis, Harvey Keitel, Michael Madsen, Christopher McDonald, Brad Pitt, Timothy Carhart, Lucinda Jenney, Carol Mansell

Screenplay by: Callie Khouri

Production Design by: Norris Spencer

Cinematography by: Adrian Biddle

Film Editing by: Thom Noble

Costume Design by: Elizabeth McBride

Set Decoration by: Anne H. Ahrens

Art Direction by: Lisa Dean

Music by: Hans Zimmer

MPAA Rating: R for strong language, and for some violence and sensuality.

Distributed by: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Release Date: May 24, 1991

Views: 373