Taglines: They’re Coming!

30 Days of Night is based on the Steve Niles graphic novel. In a sleepy, secluded Alaska town called Barrow, the sun sets and doesn’t rise for over thirty consecutive days and nights. From the darkness, across the frozen wasteland, an evil will come that will bring the residents of Barrow to their kness. The only hope for the town is the Sheriff and Deputy, a husband and wife who are torn between their own survival and saving the town they love.

Producer Sam Raimi (“Spider-Man”) brings audiences the terrifying thriller “30 Days of Night,” set in the isolated town of Barrow, Alaska, in the extreme northern hemisphere, which is plunged into complete darkness annually for an entire month. When most of the inhabitants head south for the winter, a mysterious group of strangers appear: bloodthirsty vampires, ready to take advantage of the uninterrupted darkness to feed on the town’s residents. As the night wears on, Barrow’s Sheriff Eben (Josh Hartnett), his estranged wife Stella (Melissa George), and an ever-shrinking group of survivors must do anything they can to last until daylight.

For centuries, vampires have stayed in the dark, forced to hide each morning or else be destroyed by the burning power of the sun. But in Columbia Pictures’ 30 Days of Night, based on the groundbreaking graphic novel, that’s all about to change.

Not your parents’ vampires, these are eating machines, built for one purpose — to devour human beings — and only daylight can stop them… which is why they target the remote, isolated town of Barrow, Alaska, which each winter is plunged into a state of complete darkness that lasts 30 days. The cunning, bloodthirsty vampires, relishing in a month of free rein, are set to take advantage, feeding on the helpless residents. It is up to Sheriff Eben (Josh Hartnett), his estranged wife, Stella (Melissa George), and an ever-shrinking group of survivors to do anything and everything they can to last until daylight.

About the Film

30 Days of Night began its journey to theaters with the publication of the graphic novel by Steve Niles and Ben Templesmith. The miniseries — just three books — became a career-defining moment for both. As they brought both a new look and a new story to the vampire legend, Niles’ and Templesmith’s work has been lauded as a revival of the horror comic.

“We fell in love with the idea of vampires coming to Barrow, Alaska, once the sun has set for a month,” says producer Rob Tapert, who — with producer Sam Raimi — founded Ghost House Productions to bring this kind of story to the screen. “It was a project that got us excited because it delivers a level of intensity and stylized horror that, as a young guy, I loved in these kinds of movies and to this day I still enjoy. For Sam and me, 30 Days of Night is a return to our Evil Dead roots.”

To direct, Raimi and Tapert tapped David Slade, whose first film, the independent Hard Candy, impressed them. “David has a style and way of working unique unto him,” Tapert says. “He has a very specific idea of what he wants and how he wants everything to be and then he finds a way to work this out with the actors. He is a believer in lots of tight shots, close-ups with attention to details, which frenetically ramp up his movie.”

The director says that long before getting involved with 30 Days of Night, he had bought the first edition of the graphic novel. “I love Ben Templesmith’s artwork — especially the image of Eben looking out and seeing the vampires for the first time,” he says. “After I directed my first film, I had a meeting in which an executive at Columbia Pictures mentioned that they owned the property. I said, `Hang on a minute. I would chew off my arm to do that!'”

The graphic novel is credited with reinvigorating the vampire genre. Though the creature dates back to Lord Byron in Western literature — and is many centuries older in other cultures — the vampire had, in Niles’ and Templesmith’s opinions, lost its horror. The authors saw 30 Days of Night as an opportunity to steer the genre back to its roots and away from the gothic, affected vampires that had taken over their favorite monsters. “One of the things Ben and I really wanted to do was make vampires scary again,” says Niles. “We’ve seen vampires made into Count Chocula. Teenage girls are dating them. These should be feral vampires that see humans as nothing more than something to feed on. And Ben took that ten steps further with the look of the book.”

“I was going for pure savagery, with just a hint of alien,” says Templesmith. “The classic image of the vampire is the goth, romantic ponce. I wanted eating machines.”

One of the filmmakers’ top goals was to bring the source material’s striking imagery to life. “I wanted the look of the film to be very close to Ben Templesmith’s artwork, which I very much liked,” Slade says.

Templesmith says that the filmmakers achieved that vision. “Within reason, they’ve taken the look of the movie from the page. The color’s stripped back, the vampires look like the vampires in the book — the integrity is there.”

“David and his team have really captured the stylized texture and feel of the graphic novel,” Tapert adds. “Combining Ben’s artwork with a live action style has given this movie a look all its own.”

Part of that integrity is presenting vampires that look almost — almost — human. Though the makeup effects team does rely on some prosthetics, it’s kept to a minimum. “I just wanted to tweak our vampires’ faces so that they look a little less human but still completely real,” says Slade. “They’re human enough to recognize them, but they’re not like you and me.”

To bring that vision to life, the filmmakers turned to artists from New Zealand’s Weta Workshop, who had previously brought The Lord of the Rings and The Chronicles of Narnia to the screen in Oscar®-winning fashion. “We definitely wanted to be faithful to Ben’s artwork from the graphic novel, but we also wanted to create a new Nosferatu, a shocking original design for this generation of vampire lovers,” says Tapert. “David Slade worked with Gino Acevedo from Weta and a conceptual artist, Aaron Sims, to create the final look. David worked with Aaron here in LA on some designs. Gino then took those two-dimensional sketches and brought them to life in 3-D. Gino and his team of technicians handled the molding, making, coloring, and application of all the prosthetics. They did an incredible job of maintaining the aesthetic David and I had hoped for with the vampires. ”

When these new vampires are on the screen, Slade says, one thing will make 30 Days of Night stand out: “Lots of red.”

Casting The Film

The first task the filmmakers faced was to identify the actors that would bring the graphic novel’s characters to the screen. Josh Hartnett, who stars in the film as Eben, the sheriff of Barrow, was impressed by the way that the original comic book blended all the best aspects of the genre. “It was funny and scary, a simple story but pure. I especially liked that it was character-driven — if you can follow interesting characters through the story, you can take the leap into their supernatural world.”

Before signing on to play Eben, Hartnett met with David Slade to discuss the director’s vision for the film. “We went to a bar that I’ve been going to since I was 21 — it’s very familiar to me. As we were leaving, he took a couple of pictures of this bar and sent them to me in an e-mail a couple days later. The way he exposed them, they looked haunting — I didn’t recognize the place. I thought, `This guy’s gonna make something really creepy.'”

“Josh’s take on the character is just right — though he’s by nature playing a romantic lead, he’s playing a fragmented hero, which I think is always more interesting,” says Slade. “He’s a flawed character, a person who loses his temper, a person who’s like you and me — and not an invincible strongman who goes around cutting vampires’ heads off.”

Melissa George takes on the role of Eben’s estranged wife, Stella. “She’s a very strong woman,” says George. “I love parts that show a toughness and yet vulnerability to the character. She loves the people in her town, she loves Eben, and she loves her gun.”

Tapert says that it was Slade who initially brought up the idea of casting George as Stella, and it was easy to see why. “Only Melissa brought the warmth to Stella,” he says.

Danny Huston takes on the role of Marlow, the leader of the vampires. “30 Days of Night represents a very pure kind of filmmaking: it is going to scare you,” he says. “In addition, because it’s based on the graphic novel, this movie is very stylish — the vampires aren’t your normal, everyday vampires, if there is such a thing.”

“I have a lot of compassion for someone like Marlow,” kids Huston. “We worked entirely at night, so I got into the vampire mode — driving back from the location at night, I would recoil from the sunlight. The nails, the teeth, the eyes, the prosthetics made me uncomfortable, but very sensitive as I suppose a vampire would be. Being a vampire is, potentially, a very tough life.”

“Danny absolutely owns his characters,” says Slade. “I’ve followed his career since I saw him in XTC and The Proposition — his dedication is unparalleled. For instance, he was very involved in shaping the language that his character speaks.”

Ben Foster, who takes on the role of the Stranger, was attracted first and foremost by the opportunity to work with Slade on this particular project. “I’d known David Slade socially for a couple of years and I was already a fan of the graphic novel,” he says.

Foster was intrigued by the opportunities represented in his character. “He has a level of fanaticism,” he says. “What kind of person would get involved in a group and be willing to die for that group? For me, it became a metaphor — and it was a fun one to play with.”

“In our first meeting, Ben started grilling me about the character — questions I answered gleefully,” Slade says. “He asked where the Stranger is from, and I said, `It would be great if he was from the South. Ben spent his own money learning a note-perfect Cajun accent, which is terrifying and enriched the character.”

Slade says that the Stranger performs a very specific role in the story — one rooted in vampire lore. “If this were Bram Stoker’s world, he would be Renfield,” says Slade. “The Stranger is the helper who wants desperately to become a vampire. He’s seen horrific things, lived amongst them — when the film begins, as far as he’s concerned, it’s his last night of being human — and he has great glee of the expectation of becoming something else.

“Ben repressed all the craziness that could have ensued,” Slade continues, “and instead made the role incredibly emotional. He found a way not only to make an absolutely vile, disgusting character, but one that you have absolute sympathy for — absolute sympathy for the devil.”

About the Production

As they approached production, the filmmakers’ key goal was to create a film every bit as stylish and creative as the graphic novel that inspired it. “David was very clear about referencing the graphic novel as a leaping off point,” says production designer Paul Austerberry.

“Successful graphic novels, like 30 Days of Night, are compelling both because of their story and because of their drawings,” says Slade. “To be true to the book, we had to be true not only to the story, but to the vision represented in the pictures.”

For each of the filmmakers, this required an approach of heightened realism — presenting a Barrow, Alaska that was not a comic-book world, but not our world, either.

Cinematography

Like the other filmmakers, director of photography Jo Willems first referenced the graphic novel when beginning to plan how he would shoot 30 Days of Night. The book’s art direction, color palette, and vampire design all required extensive tests in order to achieve the look that Slade envisioned.

“We were less interested in the colors of the real world and more interested in Ben Templesmith’s colors,” says Slade. “We wanted a desaturated, drained night — not a blue night like you would see in an old Western or a black dark night, but a metallic moonlight.”

Willems does note that the look of the film does differ in some ways from the graphic novel, but retains the feeling that Templesmith created; if the filmmakers had presented his drawings as they were, the film would have been too stylized. “More than seventy percent of the film is set at night — so if we went for something very dark it would be a hard movie to watch,” he says. “The way we have brought the look of the graphic novel is not so much monochromatic but a de-saturated kind of color palette, punctuated by the blood red.” In the end, Willems achieved a look that is slightly cool, almost blue, that leaves the vampire skin with a silvery sheen.

“I’ve worked with Jo Willems for about ten years off and on now,” says Slade. “I come back to Jo as often as I can because we have a shorthand for working together that makes things fast and easy. He’s a phenomenally talented DP. The look we wanted for this film required that we spend a tremendous amount of time planning the lighting, and Jo met the challenge.”

Adding to the challenge, most of the production was shot at night — in fact, 30 Days of Night utilized 33 days of night shoots.

Production Design

“I found the graphic novel very visually interesting; Ben Templesmith’s drawings are quite detailed,” says production designer Paul Austerberry. He found the monochromatic palette — punctuated by red in the blood, the flames and Stella’s fire marshal’s uniform — to be ample inspiration for creating the on-screen look of the film.

One of Austerberry’s greatest challenges was designing and building the town of Barrow, Alaska — the desolate, barren landscape that would provide the feeding grounds for the vampires. To Austerberry, the town would become almost a character of its own — at the very least, it would have to instill the feeling of dread and isolation that Slade wanted to achieve.

Though Slade preferred to depict the Barrow of Niles’ and Templesmith’s imaginations, the real Barrow did offer Austerberry some great reference material and inspiration. “Barrow is the most northern settlement in North America. They have only basic materials — there is no adornment,” he says. “The real Barrow has a lot of junk lying around; it is a long way to bring stuff to Barrow and a long way to get rid of trash as well.”

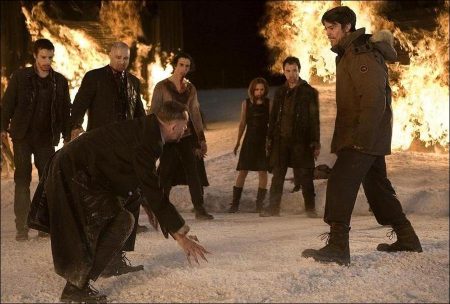

Only two sets were practical locations; the rest were built by Austerberry’s design team. Creating a fictionalized Barrow for the film gave the filmmakers a needed freedom; most interestingly, they built the town’s main street, Rogers Avenue, from scratch on a massive back lot that had once been a large outfield surrounding an Air Force base. There, the filmmakers could blow blizzards, set fires, perform stunts, and portray as much carnage as the story required.

“We’ve got black buildings and white snow — David really wanted to create a silhouetted, rigid geometry of the black against the white,” he says. “It’s like a Western town — albeit an ice Western! A place where the townsfolk live in their little town isolated in the middle of nowhere until the vampires come strolling down the main drag.”

At one point, 45 carpenters were on the set, building the town. Fortunately, during this period, the local City Council in Auckland held a recycling drive. “We got permission from the local authorities to scavenge for parts and we wound up with a huge pile of good junk!” remembers Austerberry. “It was quite useful, free, and environmentally friendly.”

Only one piece of the set was not realistic: the Muffin Monster®, the machine in which hard waste is shredded to spaghetti-like strips. The Muffin Monster is an actual sewage grinder in use at the real Utilidor in Barrow, Alaska, and in 20,000 other locations. According to Southern California-based JWC Environmental, which granted permission to re-create their machine, it “easily grinds rags, wood, plastics, rocks, towels, blankets, clothing and just about any other foreign material that can clog or damage” wastewater treatment equipment. Austerberry designed and built an oversized machine, scarier than real life — and much more capable of eating a vampire, as required in the script.

Chief among the special effects was the creation of snow: for a film set in the Arctic, the snow would almost become a character. The snow team, led by special effects supervisor Jason Durey, created over 280 tons of snow. This was the team’s largest production to date — significantly larger than their work on The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, which consisted of 35 tons.

To create the snow, the team of 30 used 150 tons of Epsom salts, 90 tons of shredded paper, 12 tons of wax, 9,000 bags of bark, over 3 tons of fake snow, 26,000 yards of white blankets, 400 boxes of eco-snow (replacing the former ingredient, potato peelings), and 7,000 liters of foam. Another key ingredient, of course, was blood. When the vampires attack, red becomes the film’s primary color. 4,000 liters of fake blood were concocted for the film. At its climax, when the town burns, the filmmakers used about 5 tons of propane gas to set it ablaze.

Stunts

Like the other departments, Allan Poppleton’s stunt team walked the fine line between recreating the work of the graphic novel and presenting a realistic world on screen.

From the very beginning, Slade wanted the vampires to do only what a human could do. “They’re not super-human, just super vicious,” he says. “Our objectives created a level of rules that we couldn’t break; we can’t break the laws of nature very much — just bend ’em a little bit. No wire harnesses was one of the rules we made. If the vampires run from roof to roof, they’re going to jump from roof to roof. Allan Poppleton was very positive and said, `We can do this.’ At our second meeting, he gave me great footage of his stuntmen leaping and jumping.”

Rob Tapert confirms, “Allan and his team have succeeded in bringing a whole level of action, violence, and gore into this movie. His team of experienced stuntmen went out there and really put themselves on the line to deliver some bone-jarring stunts and great action sequences that will make the audiences go, `How did they do that?'”

Poppleton says, “We did some research and also drew on past experience, including some roof jumping we previously did in a commercial — leaping from buildings in what we call `urban free-flying.’ All of the jumping onto vehicles or onto buildings is real — no wires, no nothing!”

To train, Poppleton’s team relied on a technique he calls `fly-metrics,’ involving several different exercises designed to get them up to speed. In addition, Poppleton collaborated with the costume and art departments to ensure that the costumes and sets would stand up under his team’s jumps.

The prosthetics from Weta Workshop provided an added challenge. “The long fingernails made grabbing onto things tricky,” Poppleton says. “Also, each performer had teeth and mouth guards created especially for him, so that nobody would bite their lips during a stunt.”

The Makeup Effects and Digital Effects

Reinventing the vampire movie required working with a creature workshop that would combine expertise and imagination into a revolutionary design. For 30 Days of Night, the filmmakers chose the Oscar-winning team at Weta Workshop to bring the vision of Ben Templesmith’s artwork in the graphic novel to life.

“On meeting David Slade, we quickly realized that this was going to be no ordinary filmmaking opportunity,” says Weta’s Richard Taylor. “I knew quickly that this film could offer so many wonderful creative opportunities for the team here in the Workshop and felt very strongly from the outset that this would be a film that Gino Acevedo, our longtime prosthetic effects head and colleague, could take on in a senior supervisory role. I proposed this concept to David, and on meeting Gino, he quickly acknowledged that he was excited about the thought of Gino supervising the makeup effects on this film for him. Over the months, we grew to become firm friends with David, and many members of the makeup team led by Gino have commented that David’s inspirations, technical know-how, and fundamental understanding of the horror genre made it one of the most enjoyable experiences of their professional careers.”

The Workshop supervisor, Gareth McGhie, was joined by Weta’s Senior Prosthetics Supervisor Gino Acevedo and Weta’s Head of Makeup Frances Richardson along with a large team of specialized technicians to create the teeth, wounds, gore, nails, projectiles, and special fabrications that would bring the vampires to life.

Most important were the teeth. No mere creatures with two little fangs, the vampires in 30 Days of Night are the eating machines that Templesmith originally envisioned. “They’re almost like shark’s teeth,” says Acevedo. “They’re wedge-shaped and quite irregular. They’re pretty nasty-lookin’.” Weta FX Technician Steve Boyle was responsible for coming up with a special technique for the dentures to enhance the look of the vampires.

The vampires also each have more than the 32 teeth in the adult human mouth. The most teeth belong to the little girl vampire played by Abbey-May Wakefield. “David wanted her teeth to be long and slender, needle-like — like a puppy’s teeth,” Acevedo says.

The vampires also have very long fingernails, which presented a challenge to the designers for a number of reasons. First, the usual way of attaching fingernails — with super glue to the actor’s nail — is easiest but can be unreliable. “Sometimes, you’ll get a fantastic take — and then discover that a nail has fallen off and the whole shot is ruined,” says Acevedo. Second, the nails had to be soft and pliable, so that stuntmen would not injure themselves or each other while filming action sequences.

To address these challenges, Acevedo and his team took casts of each actor’s hand and sculpted a new fingertip with the nail attached. “Since most of the actors and stuntpeople were unavailable to us because of distance, we had an FX technician Mark Night do most of the alginate castings up in Auckland where most of the actors were. Mark would send down a plaster cast of their hands so that we could make silicone molds of them. From these molds, we would then cast more silicone into them so that we ended up with copies of their fingers in silicone.

Then Technician Samantha Little would make plaster molds on the fingers. Once we had the molds, Sam would carefully pour latex into the molds and brush a very thin layer of latex along the edge that would later blend onto the actors fingers. Once the latex was dry, she would powder them and carefully remove them from the molds. Since we had taken casts from the actors own fingers, all the original detail was still there — including their fingerprints! Once we had all the latex finger cups, the next step would be to super glue a polyurethane nail to each one. Once the finger cups were glued and blended onto the actors fingers, makeup was applied over them so there was no way of knowing that they were wearing false finger tips and there was no way for them to accidentally come off.”

The vampires also have a very sallow, almost sickly skin tone. “It’s beautiful — it has a nice, pearlescent sheen,” says Acevedo. “We used a special body paint called `tatto-ink’ from Latona’s in Australia. Weta’s on-set Makeup Supervisor Davina Lamont mixed the right shade of a `death color’ along with a little bit of pearlescence and we were able to airbrush the colors onto the skin, giving it a very smooth and natural look that would not be possible to achieve any other way. When production began, each actor would spend 90 minutes in makeup every morning, but by the end, once we had the process down, it took 45 minutes.”

The team was also responsible for fabricating the dead huskies that signal to the town residents that the vampires have arrived. Richardson was responsible for making sure that the fur and hairwork on the huskies looked as real as possible. After taking hundreds of photographs of real huskies in the workshop in Wellington, Richardson was responsible for mapping out how the hair would lie down — the direction and the colors, from short flocking hairs near the snout to the longer hair on the body.

Even after completing all the prosthetics and builds, Acevedo’s work was not done. As the man responsible for coordinating between the production and the digital effects, Acevedo was very involved with making little tweaks that would enhance the vampires, making them look different — and definitely creepier — than humans.

“I’d take pictures of the actors in their final makeup — the pearlescent skin, red-and-black contact lenses — and I’d play with it in PhotoShop. David had the idea of splitting the eyes apart just a little bit, making them look very un-worldly. So, from the photos, I would first split them apart just a little, shrink them down about 20 percent and then gave them a little bit of a downwards tilt. Once David had seen them and approved, I gave them to Charlie McClellan, the VFX supervisor at DigiPost, who used Inferno visual effects software to go frame by frame, splitting the eyes apart and tracking each frame at the same time.”

McClellan was intrigued by director David Slade’s insistence on making the production as real as possible. “The fact that everything is at night and our vampires are really there means that the film does not have a lot of in-your-face visual effects,” he notes. “That’s interesting to me, because I like the visual effects to sit in the background — to never point towards themselves.

“With respect to the vampires it goes another step — a more interesting step — beyond that into the subliminal,” McClellan says. “If you can affect the mind of the viewer subliminally without them actually knowing why what they’re looking at is really bloody scary, that’s a good thing.”

Acevedo also worked with the team at Weta Digital to complete visual-effects work. For the climactic scene in which Sheriff Eben faces the sunrise, the workshop team’s work was only half the battle. “David wanted something of a calcified carbon look for Josh Hartnett,” Acevedo says. “We took the sugar they have here in New Zealand — not the white, refined sugar in the U.S., but the dark brown, chunky stuff — and pushed it into the clay and molded it, making some very thin appliances that were glued onto Josh’s face, head, and hands.”

Even before they applied it to Hartnett, it was clear that the work would be completed digitally to achieve the look that Slade wanted. “David was very specific,” says Acevedo. “It had to be unlike anything we’ve seen before, but it also had to look beautiful — he didn’t want it to look grotesque at all.”

To achieve the strange, darkly beautiful look the director wanted, the effects team got creative. “Very early on, we came up with the idea that once this skin started to burn, it would start to flake,” Acevedo says. “Like a piece of tissue when you burn it with a match, it’s so light that the ash just floats into the air. I had done some conceptual art along with Weta Digital artist Hovig Alahaidoyan, and between us, David found what he was looking for and let Weta Digital go to work. Weta Digitals VFX Supervisor Dan Lemmon and his team did an amazing job of bringing Eben’s charring sequence to life.”

Costume Design

When it came to costume design, Jane Holland — who headed the department — kept it simple. There would be two kinds of costumes: the utilitarian, bulked-up look of the Barrow residents, and the tailored, urban look that the vampires favor.

“What I like to do is to start with reality — if you are grounded in reality, then you can develop and get more stylized from a solid place,” says Holland. To do that, she researched what people wear in the real Barrow, Alaska — even speaking to a few people to get the feel of what it is like to live there. That said, the film did require some artistic license. “In reality,” she says, “everyone is completely covered all the time, because it is so incredibly cold there. Obviously, we couldn’t do that for the film — we wouldn’t be able to recognize the characters!”

In contrast, the vampire look is urban and contemporary with an otherworldly feel. Layered and distressed, the costumes wear and tear until they fall apart. “The vampires are very physical beings,” says Holland. “We wanted to give each one some individuality.

A good example is Marlow, the leader of the vampires. Holland dresses him in a long coat made of cashmere wool; unlike the ragged clothes worn by the other vampires, the clothes he wears are well tailored. In addition, actor Danny Huston added certain adornments — including a ring — that would emphasize his controlled and controlling manner. “By wearing a classic vintage fabric for the weight and movement — it’s almost haute couture — Marlow is trying to distinguish himself as a leader, away from all the more feral activity of his fellow vampires,” says Holland.

Holland had a few initial discussions with Ben Foster about the costuming for the Stranger. “Ben said, `I’m going to go to a surplus store and put something together,’ and I said I’d do the same thing,” Holland recalls. He sent me a photo, I sent him a photo, and we had the Stranger. It was a nice thing to have that discussion beforehand; when he arrived we had his costume, all tattered and dirtied. He put it on and just like that — there was the Stranger!”

30 Days of Night (2007)

Directed by: David Slade

Starring: Josh Hartnett, Melissa George, Danny Huston, Ben Foster, Manu Bennett, Mark Boone Junior, Mark Rendall, Amber Sainsbury, Megan Franich, Elizabeth Hawthorne

Screenplay by: Stuart Beattie

Production Design by: Paul D. Austerberry

Cinematography by: Jo Willems

Film Editing by: Art Jones

Costume Design by: Jane Holland

Set Decoration by: Jaro Dick

Art Direction by: Robert Bavin, Nigel Churcher, Mark Robins

Music by: Brian Reitzell

MPAA Rating: R for strong horror violence and language.

Distributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: October 19, 2007

Views: 145