How did you keep a secret this big?

Based on the children’s fantasy novel by British author Dick King-Smith. The Water Horse tells the story of a lonely boy in Scotland who finds a mysterious egg from which hatches a “water horse” — a mythical sea monster of Scottish legend.

The Academy Award-winning producer and special-effects team behind The Lord of the Rings join with Revolution Studios, Walden Media (The Chronicles of Narnia) and Beacon Pictures to bring this magical motion picture to the screen.

The story of The Water Horse begins when a young boy named Angus MacMorrow takes home a mysterious object he finds on the beach. He soon realizes that it is a magical egg, and finds himself raising an amazing creature: a mythical “water horse”. As he and his friend, whom he names Crusoe, form a bond of friendship, Angus begins a journey of discovery, protecting a secret that gives birth to a legend.

The special effects for the film were created by Weta Digital and Weta Workshop, the special and visual effects wizards behind The Lord of the Rings and King Kong. Walden Media previously worked with Weta Workshop to develop the fantastical creatures in The Chronicles of Narnia.

About the Film

“I look for stories that say something about the human spirit,” says Jay Russell, director of the new film The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep. “I’m fascinated by our place on earth and all the other creatures that share it with us and how each affects the lives of the other. Because this tale taps into the universal themes of magic and friendship, it applies to anyone of any age. It really is a film for everyone: it is for kids on one level, for their parents on another, and for their grandparents on yet another.”

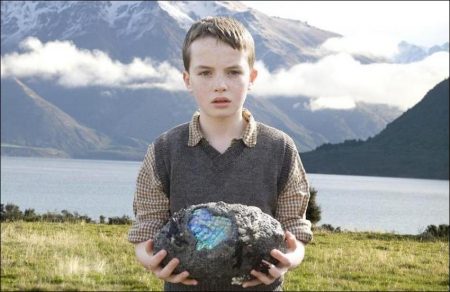

“I was really excited by the chance to show Angus’s friendship with Crusoe,” says Alex Etel. The young actor, acclaimed for his starring role in Millions, plays the boy who finds Crusoe and raises the magical creature from birth to adulthood over the course of a few weeks. “Angus is a bit of an outsider; he kind of keeps to himself. When he meets Crusoe, he’s glad to have a new friend, but also excited to have a secret. It’s the most important friendship of his life.”

For Russell, that relationship parallels an important aspect of Angus’s life. “The relationship between Angus and the Water Horse is of great importance, because as the creature grows, it really becomes a quite beautiful metaphor for the relationship Angus once had with his father,” notes the director. “Crusoe helps him grow from a young child towards maturity. That’s the simplicity of this story; it’s just a wonderful way to tell the story of a child growing up and accepting the realities of life.”

Dick King-Smith, who wrote The Water Horse, the book on which the film is based, says that he was particularly delighted to depict the story of a young boy’s connection to the world around him. “I think what intrigues people about the story is the mystery,” he says. “No one really knows for sure if the water horse is there, no one knows what it’s going to look like. You can let your imagination run riot; I think that’s the fun of it. I think the appeal of this story is its simplicity; this is a straightforward story about the relationship between a family of human beings and one strange individual animal and the effect it has on that family.”

King-Smith says that there is another aspect of the story that has stayed with him. “I think there is a common theme of courage that runs through my animal stories: courage,” says the author, who also wrote the book Babe: The Gallant Pig. “It can be physical courage or moral courage, but in my stories, an animal is confronted with a predicament or trouble of some sort, but wins through by sheer determination. That’s a theme that intrigues me.”

To bring this very special animal to life, the filmmakers called upon the visual-effects wizards at Weta Workshop and Weta Digital, who previously created the effects for The Lord of the Rings, The Chronicles of Narnia, and King Kong. “This is exactly the kind of movie we love making,” says Richard Taylor, workshop supervisor for Weta Workshop. “We get to develop a beautiful little creature like this, but the fact that it transforms over the length of the movie and grows ultimately to become the adult water horse gives a huge opportunity for design exploration for us. We were able to interact with Jay Russell and ultimately with our team to make some very special things for a really lovely film. It is not often a movie like this comes along in your career.”

Producer Barrie M. Osborne, who previously teamed with Weta as a producer of the Lord of the Rings trilogy, returned to New Zealand to take on the same role on The Water Horse. Osborne agrees that Russell, previously the director of the highly regarded family films My Dog Skip and Tuck Everlasting, was the right man to bring The Water Horse to the screen. Just as in those films, Osborne says, at the heart of The Water Horse is a gentle coming-of-age story. “The film chronicles the unfolding of this young man’s journey,” he explains. “He comes to terms with a great tragedy, and through his friends and through this creature, he finds at the other end hope and beauty and life.”

“Jay is very intelligent,” Osborne continues. “He gives the movie his all. He’s very, very passionate about what he’s doing. It’s a joy to work with him.”

“I enjoy the imagination and scale of the story — it’s thrilling — but for me, the movie is about heart,” says producer Charlie Lyons. “It is touching and a reminder that when you lose your childhood, you have to fight to keep your imagination. If a kid tells you they’ve got a sea monster in the shed, you’d better listen. The Water Horse is a reminder that there is beauty in the world, and that life is a treasure.”

The Casting

At the center of The Water Horse is Angus, the young Scottish boy who befriends the title character. Director Jay Russell had seen Alex Etel in the lead role in Danny Boyle’s Millions and arranged to meet the young actor in England. “As soon as I put the camera on him he lit up the screen and I knew he was our boy,” says Russell. “It’s not simply a matter of finding an experienced actor — when working with young actors, none of them has a lot of experience. You’re looking for something else — an undercurrent, gravitas, resonance beneath the performance. Alex brings that, and I knew he was perfect for the part.”

Etel describes his character as a lonely boy who becomes more so when his father goes off to war. “His dad was his only friend, really — the only person who was close to him,” says Etel. “Crusoe kind of becomes a stand-in for his dad — the things they do together are the kinds of things a father and son would do together. When he learns to let go of Crusoe, he also learns that the life he had before his father went off to war will never be the same.”

In the film, Angus develops a strong bond with Crusoe, the mythological creature that turns out to be quite real. “Angus needs Crusoe just as much as Crusoe needs him,” adds Etel. “This is a story about a boy growing up, and Crusoe helps him do that at a time when he needs the help the most.”

Etel says that one of the most exciting aspects of working on The Water Horse was the idea of making a movie that his whole family would enjoy. “I like Angus’s and Crusoe’s story, and I think parents will, as well,” he says. “You always hear that a movie is `fun for the whole family,’ but this is one that relates to kids on our level but also has enough for the parents.”

Actor Ben Chaplin, who has several important scenes with Alex, has high praise for the young actor. “I can’t think of another 11-year-old boy who would have been as easy and as much fun to be around,” says Chaplin. “He’s really bright, stimulating, quick, and witty. We had a greater bond than our characters are supposed to have — or, at least, a bond that was more demonstrative, more open. I hope it comes across because he has been a real trooper.”

Playing Angus’s mother, Anne, is Academy Award® nominee Emily Watson. “I had one person in mind for this role and that was Emily Watson,” says Russell. “Emily was it — if she had said no, I don’t know what I would have done. She always brings a complexity to her roles that has nothing to do with overt behavior and speech.”

“I think The Water Horse is in the great tradition of children’s stories with a realistic background,” says Watson. “I think children understand how high the stakes are. For my character, Anne, it’s easier to let Angus live in a fantasy world than confront the pain in his life.”

The filmmakers called upon Ben Chaplin to play Lewis Mowbray, one of the most secretive and enigmatic characters in the film. “Lewis’s past is a deep, dark secret,” says Russell. “He’s experienced more life and death than any of the other characters in the piece, but it’s affected him to the point that he’s buried it well underneath the surface of his behavior.”

“He’s a bit mysterious at the beginning,” says Chaplin. “He is of fighting age, but isn’t in the army. When he turns up from nowhere, two days late to take up a position as a handyman for Angus’s mother, we don’t really know his history.”

“Ben Chaplin’s a very accomplished actor. I’ve been a fan of his for years,” says Russell. “He’s played so many different kinds of roles that I knew he could pull this off. When we first met there was an instant connection between the two of us in terms of the character and an approach to the character and an approach to acting in general. He knew early on that it was going to be important for him to bond with Alex because they were going to share so many scenes together.”

Veteran actor David Morrissey takes on the role of Captain Hamilton. “I think David has the most difficult character to play because Captain Hamilton is a man who’s so unsure of himself,” says Russell. “David did an entire biography of Hamilton to help him approach the character. None of this is in the film, but David knew exactly where Hamilton went to school as a boy, exactly what he did on holidays growing up, and most importantly, that he was a privileged person. While there was a certain expectation of Hamilton as a man, he never had the proper preparation for the responsibility of leading an army troop. He is a man putting on the show of being in charge and being a leader, but he knows deep down he’s not prepared for that, that he got that position by privilege. David found that arc in the character.”

“He is an officious man,” says Morrissey of his character. “He has a great sensibility about him, but he has a job to do and he won’t let sentiment get in the way of that job.”

For Russell, finding the right actor to play the role of the narrator was crucial. “I felt very strongly that we had to get not a good actor but a great actor for that part,” says Russell. “Because he’s on screen such a small amount of time, I wanted us to connect with him instantly and be taken with the story that he has to tell. You can only do that with a great actor like Brian Cox.”

Just as when he was searching for a boy to play Angus, Russell also looked for a young woman with an inner life when casting the part of his sister, Kirstie. “The part of Kirstie was again a difficult part to cast because, as in casting Angus, I knew the role was likely to be filled by an inexperienced young actor,” says Russell. “It’s important to me when there’s a family in a movie that they look like they belong and came from the same gene pool. Priyanka Xi has the same light in her eyes and the same spirit as Emily, and has a physical resemblance as well. I breathed a great sigh of relief when I found that she was a good actor.”

Bringing Crusoe to Life

Of course, there was one more character that would make a mark on the film: the title character, Crusoe. The task of bringing Crusoe to life was given to Weta Digital and Weta Workshop, who had been responsible for the effects work on the Lord of the Rings trilogy, King Kong, and The Chronicles of Narnia.

“Because the creature is such a central character to the film, the main thing we tried to do is to define his personality,” says Academy Award® winner Joe Letteri, Sr., visual effects supervisor at Weta Digital. “The most important thing was that we really wanted him to be an animal — he had to have a personality, but we didn’t want to humanize him. Also very important was that we get across the idea that Crusoe is a creature Angus can see himself in.

“This film required that we do things that people haven’t seen before,” adds Letteri. “The special-effects department had a huge role during filming because Crusoe had to fit into so many real-world elements. Everything that they did with the lighting, the water interaction, moving things around on set — all of those things help immeasurably to make it feel like Crusoe was actually there in front of the camera when the scene was shot.”

The first step in the process was to design the mythical creature. Since no one has seen a water horse, the field was wide open. Russell says, “When I originally sat down to design it with Crusoe conceptual designer Matt Codd, we looked at all different sorts of animals and creatures. We felt that because we were creating our own version of this legend, we wanted to have something unique. In the original concept drawing of this creature, we used about a half a dozen different animals in the face and in the body of Crusoe. If you look closely at the original concept drawing, you will see he has an eagle’s eye and the snout of a horse. There’s some dog in there, there’s dinosaur — there’s even a little giraffe, because we wanted audiences to have an odd sense, in which they think, `I’ve seen that creature but I’m not quite sure what it is.'”

In addition, because the film follows Crusoe as he grows — in a matter of weeks — from infancy to adulthood, the teams would have to design several stages of growth for the animal. Creature art director Gino Acevedo, who serves as both a senior prosthetics supervisor for Weta Workshop and art director for Weta Digital, says that the design involves several distinctive elements so that the audience knows that it is watching the same creature from scene to scene. “We gave him specific little markings and coloration, so that the creature has a nice flow as it grows, all the way through to the very end of the film.”

Still, Crusoe does go through changes as he grows. “Jay wanted the infant to be quite light in color, then gradually become darker as he grows up,” notes Acevedo. “When he becomes a teenager, he has lost a bit of his puppy fat and he is starting to fill out his shape; he has more muscle definition. When we come to the adult Crusoe, his skin has a beautiful color transition, from dark on top to light on the underbelly.”

Acevedo continues, “When we were trying to figure out what the actual size of Crusoe was going to be, Weta Digital made a model of Angus and stuck him on the back of Crusoe — we could play around, sizing Crusoe until we found a comfortable fit for both of them.”

Acevedo and the team at Weta picked up the ball from there, refining and fine-tuning the design according to Russell’s instructions. Adding characteristics of seal and plesiosaur and some very fine wrinkles and details, Weta created a clay sculpture — called a maquette — of the final creature. When approved by Russell, Weta made solid, urethane copies of the final Crusoe, which were used to create paint schemes for Crusoe.

For this, Acevedo again went back to real-world inspiration for the magical creature. “We took into consideration the environment in which Crusoe lives when we were designing the color for him,” says Acevedo. “The water in Scotland is quite murky and there is a lot of seaweed floating around. Crusoe is a magical creature that has been living there for hundreds and hundreds of years. He would have to have been able to camouflage himself quite well; if not, he would have been captured and ended up in Sea World!”

With that starting point, Acevedo began designing a paint scheme with mottled patterns. “At the same time, because Crusoe isn’t a real creature, we pushed the envelope just a little bit to come up with something a little bit more interesting,” Acevedo notes.

When Acevedo had a design, the torch was passed to Weta Digital, who scanned the urethane creature into the computer to create a 2-D computer model, and from there, built Crusoe’s skeleton, muscle structure, and skin. His skin, most of all, represents a significant technical advance for Weta Digital. “We have a new skin technology that we developed for Crusoe,” explains Letteri. “We can see the subtle changes in his skin as he goes in and out of the water.”

With the design of the creature in place, the next challenge fell to the animators to bring him to life. “What we discussed early on with Jay, in terms of defining an animal personality for Crusoe, was that we would look at dogs — especially at the puppy stage, because that’s when the audience really gets to know Crusoe,” explains Letteri. “Dogs are very expressive — though they aren’t human, you can still read their emotions.”

In addition, Crusoe would have to be emotive in similar ways. “Because Crusoe can’t talk, his expressiveness has to come from the eyes,” says Acevedo.

The animators began their work before one frame of film was shot. Testing how the creature might behave, they provided inspiration for the actors, who, during filming, would be reacting to a puppet (that would later be digitally replaced) or to nothing at all. “We did a little bit of exploration right away, just to get a sense of how playful he is, how isolated he might feel at times, what his reaction might be to Angus to the people around him. We used that as a starting point.”

Richard Taylor, workshop supervisor for Weta Workshop, says that using a puppet to interact with the actors and real-world elements during filming is a technique that has worked well — and in Oscar®-winning fashion — for Weta. “In the films we have done in the past, we have found that the more there is a physical entity on set, the better. This was seen so well with Andy Serkis playing first Gollum and then Kong. Something like this can actually add so much to the performance — not of the creature, but of the actor playing opposite the creature. The digital effects department can do the best work in the world, but if the actor isn’t reflecting the emotional interplay of that creature, you have nothing. This gives the film a really lovely way for the actor to do something very, very special and it gives us the chance to play around in the bathtub with a rubber toy.”

“These puppets are cast out of silicone, so they are quite wobbly,” explains Acevedo. “We use rods to manipulate the puppet and it is pretty amazing how they can move and swim inside the water. We also have a blue version of the `puppy’ water horse, which really helps Weta Digital remove it from each shot.

“There was a funny incident using the puppet,” Acevedo recalls. “In one scene, Crusoe is tugging at one of Angus’s father’s boots. The puppet was connected by a cable to the boot and Alex was actually pulling. Jay kept telling him, `Pull harder, pull harder!’ Alex pulled so hard the head of the puppet fell off. We had to make another puppet — but this time, we put the cable in the mouth so he could pull as hard as he liked without worrying about the head coming off.”

When the story begins, Crusoe has yet to be born from his magical egg. The egg — which is special and distinctive enough that Angus spots it and brings it home — was also designed by Weta. “I played around with a lot of different designs and shapes,” notes Acevedo, “and then one night I had the thought that being here in New Zealand it would be neat to use Paua [abalone] shell. It’s a very beautiful shell that has a magical feel about it. John Harvey, one of our workshop technicians, does a lot of diving and found a huge piece of Paua shell, which Jay agreed worked perfectly.

“To make the egg, we started with a Plasticine clay, then spent a lot of time at the beach picking up bits of shell and coral that we added onto it. Once the sculpture was completed, we cast a hard urethane copy, which we cut away and added the Paua shell inside,” Acevedo continues. “Guy Williams at Weta Digital came up with the idea to use little magnets to hold the pieces on. It was just like a jigsaw puzzle that could be reset for as many takes as needed.”

Weta Digital was also responsible for designing and building Crusoe’s underwater world. Says Letteri, “After a pre-visualization video, in which we showed Jay what it would look like under the surface, we began building the underwater canyons, the plants, the fish, boats, and everything else that we see under there. A greater challenge was the lighting under water, because Jay wanted to capture that magical quality of diffused light that you see under water. We also want to have Angus look believable — that he is comfortable on Crusoe when he needs to be but also scared when he needs to be.”

Locations and Shooting

Before production began, the filmmakers determined that though most of The Water Horse: Legend of the Deep would be shot in New Zealand, the film would have one location that had to be shot in Scotland: the exteriors of the estate where Angus lives with his mother and sister. The company filmed at Ardkinglas House, an estate in the countryside with a house that dates back 100 years.

“Jay had already visited Ardkinglas House and fallen in love with it, so it was the first place I went on the location scout,” says production designer Tony Burrough. “I had been to Scotland many times, but when I got to Ardkinglas, I saw it with different eyes as I put it into the context of our story.

“Though there have been different houses on that plot of land for centuries, they had been destroyed by fire,” Burrough continues. “The house that stands there now was actually built in 1910, but it looks a lot older because it was designed to echo the stately manor houses with medieval battlements, parapets, and towers. Although it is not colossal, it has echoes of older architectural styles. When you go into the house, there are pictures on the walls of the beautiful Georgian house that burnt down.”

The estate has been owned by the same family for a century. Along with the traditional activities of property letting, hill farming, forestry, and hunting, the estate supports a range of diverse business activities, which include a plant nursery and garden center, a shellfish farm, retail shop and oyster bar, a quarry, a salmon farm, and smolt-rearing factory.

While in Scotland, Burrough found the time to research the areas that would serve as inspiration for the rest of the film when production resumed half a world away. “I drove up to Loch Ness and visited one or two of the villages to get a sense of how things are now and research what life was like there two generations ago,” he says.

The majority of the film was shot in New Zealand — an ideal location not only because the country has a well-established film community that has proven it can host productions of any magnitude, but also because it has a varied landscape, allowing for a multiple locations. Add to that the fact that Wellington is home to Weta Workshop and Weta Digital, two key players on this effects-heavy film.

“When I arrived in New Zealand, my first task was to `find Scotland,'” says Burrough. “I was shown quite a few hours of aerial footage and the one that took my eye was down in Queenstown. Traveling around in the helicopter, I realized that it could work. When I saw the little track going down the side of the lake, I knew I had found it. I got out of the helicopter and I was surrounded by gorse [vegetation normally found in Scotland]. My first thought was, `Wow, this is Scotland-plus.'”

For producer Barrie M. Osborne, who previously produced the Lord of the Rings trilogy in New Zealand, the film was something of a homecoming. One of his jobs was finding suitable matches for Scotland Down Under. “We found a great location on the far side of Lake Wakatipu, which is a sheep ranch with 40,000 sheep. We decided to film there, but it was not an easy choice.” Among the challenges: although Wellington, at the southern end of the North Island, has a growing and able film community, Lake Wakatipu is near Queenstown, over 400 miles away, in the middle of the South Island. “There are some talented technicians there, but they primarily work in commercials. We were fortunate in enticing John Mahaffie, a great cameraman/second unit director who lives in Queenstown, to lead our second unit, but we had to travel and house our primarily Wellington-based crew. In addition, our primary location was on a sheep ranch that doesn’t have any paved roads — only dirt farm roads. We had to improve some of the farm roads, reinforce a bridge that was in danger of collapsing, and ferry our crew back and forth across the lake every day. Quite an exercise in scheduling. But we all felt the extra effort was well worth it — what we captured on screen is breathtaking.”

On the first day of principal photography, the cast and crew gathered at a jetty on the edge of the lake to take part in a traditional Maori blessing. Elders from the local Maori tribe performed the ceremony and presented director Jay Russell and actors Emily Watson, Alex Etel, Ben Chaplin, and David Morrissey with the traditional green stones which protect the wearer against bad luck.

The first three weeks of filming took place across the lake from Queenstown and involved transporting over 200 cast and crew by boat to the sets. Winter was just beginning in Queenstown and already the mountain bore a frosting of the first snows. Most importantly, the lake remained calm for the most part — an unusual phenomenon for the time of year. The journey across the lake allowed the cast and crew to take in the stunning vistas during the day and the incredible star-studded skies at night.

“It was a tough location, because we were working at night,” explains Etel. “It was really cold and we were close to the water. We were using rain towers and we had freezing cold rain pouring down on us all the time. The wardrobe people were really professional; they kept me as warm as they could.”

However, those kinds of conditions can actually help performance as Morrissey explains. “The characters are in a storm and we have to evoke that, and we evoke that with very cold rainwater. That’s great for an actor. It’s wonderful to feel that you are there and you are doing it. The water is choppy, the waves are coming, and the rain is freezing. It gives me something to work with; the uncomfortable nature of it is very important.”

Following completion of the work in Queenstown, the production upped anchors and flew by charter to continue work at the Stone Street Studios in Wellington. The work there was principally stage work utilizing the incredible sets designed by Burrough. Most impressively, the production also built an enormous outdoor filming tank, one of the largest in the world, holding over 4.2 million liters. “It was eight feet deep, covering about one-and-a-half times the area of a football field,” explains Osborne. Measuring approximately 70 meters by 100 meters, the tank was surrounded on three sides by a 24-foot-high exterior blue screen.

According to Osborne, the mechanical effects, camera, grip, and lighting teams all had a say in the design of the tank. “We needed something large enough to safely flip our large patrol boat in, with room for the stunt crew to leap from. We needed a track to move our blue-form Crusoe on, so our mechanical-effects crew designed a track and a pneumatic carriage for Crusoe that ran diagonally across the tank. At the last minute, I realized we needed much more flexibility than the track allowed, so in four days’ time, they came up with a Crusoe jet-ski rig that did the trick. We needed ways to move our camera quickly across this large area of water and to light across it without eating up production time. Because we were shooting on an outdoor tank, we would face some really tough winter weather,” he says. The crew factored all of this into their preplanning for the shoot.

For Etel, the scenes in the tank required learning a new skill: when production began, he was barely able to swim. In order to be able to complete the work himself (rather than relying on a stunt double), Etel trained for weeks with stunt coordinator Augie Davis.

Davis explains, “The production built a Crusoe underwater riding rig, which involved Alex going underwater for a great length of time. Alex had about 20 underwater shots, and for each shot, he had to hold his breath for about 20 seconds at a time. He held onto the underwater rig and wore a weight belt to keep him under. He was surrounded by safety divers and had an extra air supply he could reach for at any time. Alex took to the water exceptionally well and spent a tremendous number of hours with our diving instructor. He can hold his breath for roughly 45 seconds — that’s impressive for somebody who has not been brought up in this kind of environment.”

Etel enjoyed his stunt training. “Augie was one of the first people I met on the film and he taught me a lot. The stunties are really fun to work with and they are very professional. He taught me a lot about the water and how to hold my breath. It was really helpful to know all that before we got to the tank.”

The Production Design

For production designer Tony Burrough, who had previously collaborated with director Jay Russell on Tuck Everlasting and Ladder 49, “The most important thing was to capture the fact that we were in Scotland in 1942,” he says. “We had to create our own believable Scotland in New Zealand. It was very important that the world we were creating was totally believable so that the creature, which is obviously fantastical, could also be believable.”

“Jay and I have worked together enough that I know if I give him a beautiful set he will certainly use it,” Burrough says. “Jay loves to create an atmosphere, to use the magical quality you can create with film. He likes to tell a story with pictures as well as dialogue, and it’s my job to help him create those pictures.”

As he was creating the interior of Killin Lodge on a soundstage thousands of miles from Scotland, Burrough had a free hand in his designs. “I started looking at various references — English country manor houses and big Scottish hunting lodges,” he says. “In the end, we built a hybrid house that was based on all those different images. I took a wonderful fireplace I had seen in one house, a fantastic staircase, and interesting door details. I wanted to give the house a certain history but I also had to make the interior fit the exterior. I knew the existing house wasn’t that old, so what I created a Victorian house harking back to the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, adding in a little bit of medieval stonework. That was exactly what the Victorian architects did; they stole from different eras and over-elaborated, over-designed, and over-detailed.

“Because Ardkinglas House — the real house in Scotland that we used for the exteriors — is so large, we designed the interior rooms to be very big, as well,” adds Burrough. “We also kept in mind that the interior set would have to accommodate the big chase that happens in the house. The camera can sweep through the rooms, following the chase into the dining room, where everyone is seated at a huge table for a formal dinner.”

“Detail is very important to me,” Burrough continues. “Because we are following a little creature — 6 or 8 inches long — around the house, being chased by a dog, the camera has got to be very low, we are going see the floors — the parquetry, the passage stone floor, and the kitchen floor. All the different textures and surfaces are important.”

Another detail that Burrough found especially interesting, even if few moviegoers will notice, is the creation of the family crest. “I created the crest because I wanted the house to have a bit of history,” he says. “We don’t know the family because they are not in the film, but their presence is there. Because the house is by the loch and the loch led out to the sea, the sea is in the motto and there are sea creatures in the family crest. My thought was that the house may have had a history of being associated with mythical sea creatures. It was a great opportunity to use little bits of water horse imagery.”

The workshop was also a very important set. “It’s Angus’s secret world,” says Burrough. “It was his father’s workshop. Angus has pictures of his father, charts, and a calendar on the wall. It’s his sanctuary, a private world where he can escape from reality.”

The Cinematography

For veteran director of photography Oliver Stapleton, the main attraction of the film was the chance to work with Weta Digital. “It was a bit of a departure in terms of work I had previously done, in that it was going to have a lot of CGI involved and a lot of very difficult technical sequences,” he says. “With digital imaging, you have more choices than ever, but freedom can also mean a lack of discipline if you are not careful — you might think, `I’ll just shoot it flat and we’ll fix it later.’ The more I know about digital imaging, the less I think that’s true — I think it’s still absolutely essential that the ingredients are correct.”

Initially, Jay Russell and Stapleton agreed on the look of the film. “The style is quite traditional in some ways,” Stapleton notes. “There is so much in the film that’s strong in terms of story that the classical camera work is the best way to reinforce what is already quite a spectacular and action-packed couple of hours.

The Costumes

“The most important thing in this story is that you have got to believe in the water horse,” explains costume designer John Bloomfield. “To make that happen, you have to make certain that the whole background is believable, and that includes the costumes. Everything we do has to be so real that you never for one moment doubt that this is a real world.

“1942 is very well documented,” Bloomfield continues. “Actually, it was the year I was born, so I know it well. The film is set in Scotland, so it is not a period of great color. It was a period of utility clothing — nobody spent any money on clothes — so I didn’t look at fashion drawings from 1942; I was looking for things that would have been bought in 1935. It was simply a question of keeping to that monotone, sensible look.

“When I got to New Zealand, I found a terrific source of fabrics,” Bloomfield continues. “The best thing of all is knitting. I had some knitters working here who just did a terrific job, and, of course, the quality of New Zealand wool is incredible. That helped give it a real look — the weight of fabric that you see in the clothing that we don’t wear today.”

Bloomfield notes that despite Alex Etel’s maturity, he is still a modern boy. “The difficult thing with a young boy — and Alex is absolutely terrific — is persuading him that these clothes are not funny,” says Bloomfield, explaining that Etel was open to his character’s costume when he saw it was true to the period. “Getting his trousers up around his waist properly, wearing a baggy shirt, those boots with the big wool socks. I showed him photographs of real clothes and I told him things that I remember of what it was like wearing all that wool next to your skin. He really got into it. The scene on the beach shows a lot about his character — he is standing there wearing all his clothes, the short trousers, his sweater, his long socks and his boots, while the other kids on the beach are playing in their swimming costumes. It shows how isolated Angus is.”

Bloomfield’s other challenge was outfitting the army unit that comes to Killin Lodge. “The army follows King’s Regulations and we just had to recreate exactly what we saw in all the pictures and the newsreels. I have done my best, but it is a minefield. You could read books and books about King’s Regulations and never get it right; everybody has a different opinion. There are lots of photographs, but photographs are often deceiving. When having their picture taken, people would put on their best things, things that they never actually would wear when they were in the field. It is always quite difficult to get the reality of camp life and exactly what went on.”

“Authenticity is a word that always comes up when you’re doing a period piece,” says Jay Russell. “I wanted to make sure that the military not only looked like military, but acted like military. The only way you get that is by having someone come in and train the troops. We were very lucky to get a soldier in the New Zealand army named David Strong. I’m sure a lot of these extras had no idea what they were in for when they said they’d like to be an extra in a movie; they didn’t realize they were actually going to have to join the army, but David had them out marching, doing drills, saluting, and firing off big guns.”

The Water Horse – Legend of the Deep (2007)

Directed by: Jay Russell

Starring: Emily Watson, Alex Etel, Ben Chaplin, David Morrissey, Geraldine Brophy, Nathan Christopher Haase, Eddie Campbell, Craig Hall, Megan Katherine, Elliot Lawless, William Johnson

Screenplay by: Robert Nelson Jacobs, Terry George

Production Design by: Tony Burrough

Cinematography by: Oliver Stapleton

Film Editing by: Mark Warner

Costume Design by: John Bloomfield

Set Decoration by: Dan Hennah

Art Direction b: Simon Bright, Dan Hennah, John Hill, Brad Mill

Music by: James Newton Howard

MPAA Rating: PG for some action/peril, mild language and brief smoking.

Oistributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: December 25, 2007

Views: 56