A stiff drink. A little mascara. A lot of nerve. Who said they couldn’t bring down the Soviet empire.

Charlie Wilson’s War is the outrageous true story of how one congressman who loved a good time, one Houston socialite who loved a good cause and one CIA agent who loved a good fight conspired to bring about the largest covert operation in history.

Oscar winners Tom Hanks (Forrest Gump, Philadelphia), Julia Roberts (Erin Brockovich, Closer) and Philip Seymour Hoffman (Capote, The Savages) team with Academy Award-winning director Mike Nichols (Closer, The Graduate) and Emmy Award-winning screenwriter Aaron Sorkin (A Few Good Men, The West Wing) to bring George Crile’s best-selling book to the screen.

Charlie Wilson (Tom Hanks) was a bachelor congressman from Texas whose “Good Time Charlie” personality masked an astute political mind, deep sense of patriotism and compassion for the underdog. In the early 1980s, with the looming advance of a Russian invasion, that underdog was Afghanistan.

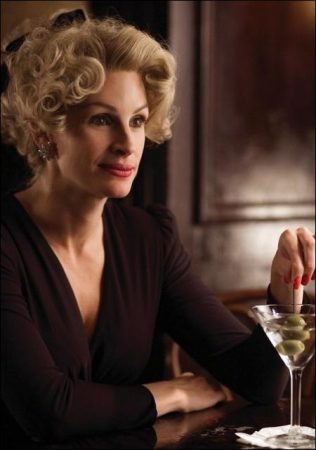

Charlie’s longtime friend, frequent patron and sometime lover was Joanne Herring (Roberts), one of the wealthiest women in Texas and a virulent anticommunist. Believing the American response to the invasion of Afghanistan was anemic at best, she prodded Charlie into doing for the Mujahideen-the country’s legendary freedom fighters-what no one else could: secure funding and weapons to eradicate Soviet aggressors from their land. Charlie’s partner in this uphill endeavor was CIA agent Gust Avrakotos (Hoffman), a bulldog, blue-collar operative who worked in the company of Ivy League blue bloods dismissive of his talents.

Together, Charlie, Joanne and Gust traveled the world to form an unlikely alliance among Pakistanis, Israelis, Egyptians, lawmakers and a belly dancer. Their success was remarkable. Over the nine-year course of the occupation of Afghanistan, United States funding for covert operations against the Soviets went from $5 million to $1 billion annually, and the Red Army subsequently retreated from Afghanistan.

Charlie Wilson’s War is a 2007 American comedy-drama film, based on the story of U.S. Congressman Charlie Wilson and CIA operative Gust Avrakotos, whose efforts led to Operation Cyclone, a program to organize and support the Afghan mujahideen during the Soviet–Afghan War.

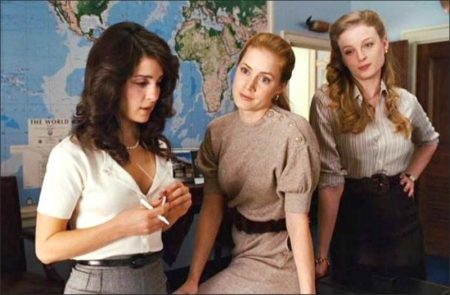

The film was directed by Mike Nichols (his final film) and written by Aaron Sorkin, who adapted George Crile’s 2003 book Charlie Wilson’s War: The Extraordinary Story of the Largest Covert Operation in History. Tom Hanks, Julia Roberts, and Philip Seymour Hoffman starred, with Amy Adams and Ned Beatty in supporting roles. It was nominated for five Golden Globe Awards, including Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy, but did not win in any category. Hoffman was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

The film was originally set for release on December 25, 2007; but on November 30, the timetable was moved up to December 21. In its opening weekend, the film grossed $9.6 million in 2,575 theaters in the United States and Canada, ranking #4 at the box office. It grossed a total of $119 million worldwide—$66.7 million in the United States and Canada and $52.3 million in other territories.

Charlie, Joanne and Gust at War: A Detailed History

In December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, an event much expected by the CIA. As Steve Coll wrote in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Ghost War”: “The CIA had been watching Soviet troop deployments in and around Afghanistan since the summer, and while its analysts were divided in assessing Soviet political intentions, the CIA reported steadily and accurately about Soviet military moves.

By mid-December, ominous, large-scale Soviet deployments toward the Soviet-Afghan border had been detected by U.S. intelligence. CIA director [Stansfield] Turner sent President Carter and his senior advisers a classified `Alert’ memo on December 19, warning that the Soviets had `crossed a significant threshold in their growing military involvement in Afghanistan and were sending more forces south.’ Three days later, deputy CIA director Bobby Inman called [National Security Advisor Zbigniew] Brzezinski and Defense Secretary Harold Brown to report that the CIA had no doubt that the Soviet Union intended to undertake a major military invasion of Afghanistan within 72 hours.”

As Crile illustrated in “Charlie Wilson’s War,” this invasion changed President Jimmy Carter’s philosophy toward the USSR. “It radicalized him,” the journalist observed. “It made him suddenly believe that the Soviets might truly be evil, and the only way to deal with them was with force.”

Crile continued in his book: “`I don’t know if fear is the right word to describe our reaction,’ recalls Carter’s vice-president, Walter Mondale. `But what unnerved everyone was the suspicion that [Soviet president] Brezhnev’s inner circle might not be rational. They must have known the invasion would poison everything dealing with the West-from SALT [Strategic Arms Limitation Talks] to the deployment of weapons in Western Europe.’”

Overt force was not a first option for the administration. This was the Cold War after all, and the two superpowers each sat upon an enormous arsenal of nuclear weapons, ominous enough to easily conjure up World War III. Too, after the wrenching turmoil of Vietnam, America was weary of entering into another conflict in which there was no certain end date.

Carter would, however, set certain wheels in motion. He authorized a boycott of the Summer 1980 Olympic Games scheduled for Moscow, instigated an embargo on grain sales to the Soviets, fast-tracked a 1977 directive known as the Rapid Deployment Force and introduced The Carter Doctrine. Crile elaborated, “The Carter Doctrine [committed] America to war in the event of any threat to the strategic oil fields of the Middle East. His most radical departure, however, came when he signed a series of secret legal documents, known as the Presidential Findings, authorizing the Central Intelligence Agency to go into action against the Red Army.”

Thus began the agency’s covert operation to arm Afghan rebels for self-defense. The nascent scheme was modest and, as Crile suggested, tied to “the CIA’s time-honored practice never to introduce into a conflict weapons that could be traced back to the United States. And so the spy agency’s first shipment to scattered Afghan rebels-enough small arms and ammunition to equip a thousand men-consisted of weapons made by the Soviets themselves that had been stockpiled by the CIA for just such a moment.” Unfortunately for the Mujahideen, this was not an impressive cache-mostly rifles from WWI with a limited supply of ammunition with which to load the purloined weaponry.

The Afghan freedom fighters proved to be some of their own best assets. Led by chieftains and mullahs, these warriors called for jihad against the tens of thousands of Soviets who began pouring in the country. However, even with the CIA’s limited help, they were no match for the Soviet military machine. Crile pointed out in his book, “The Afghan people would suffer the kind of brutality that would later horrify the world when the Serbs began their ethnic cleansing. Soviet jets and tanks would lay waste to villages thought to be supporting guerillas. Before long, millions of Afghans-men, women and children-would begin pouring out of the country, seeking refuge in Pakistan and Iran.”

It was their plight and determination that touched Texas’ 2nd District delegate to the House of Representatives. Charlie Wilson possessed a focused interest in history and foreign affairs, as well as an abiding antipathy towards the Soviet Union. The Afghans’ spirit against the overwhelming and brutal Soviet force won his favor. Fortunately for them, he happened to sit on one of the subcommittees in the House that was at the intersection of the State Department, the Pentagon and the CIA: the Defense Appropriations Subcommittee. And after a visit from a well-heeled socialite and strident anticommunist, it would only be a matter of time before he cashed in a number of favors for the people of Afghanistan.

Wilson saw the devastating effects of the Soviet invasion firsthand when taken to Afghanistan by Houston millionaire Joanne Herring on a trip that began in a typically unorthodox fashion. “Joanne approached me about 1981,” recalls Wilson. “I had already taken notice of the Afghan war, and I had doubled the appropriation for the CIA to supply the Mujahideen with weapons, but that was only a very small step. It was something I did impulsively, just because I became angry at the atrocities that were being committed there. Nobody thought the Afghans could successfully resist the Soviet Union, but Joanne was on a personal mission. She was the honorary consul for Pakistan, but she was far more than that.

“She really had the ear of Zia, and he was interested in what she said,” Wilson continues. “She was a strong anticommunist and had been to the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan, so she’d actually seen what was going on. Joanne persuaded me to go to Afghanistan and take a look myself, because she was desperately trying to get someone interested in it. She was outraged about the Soviet atrocities taking place in Afghanistan, and she was concerned about the expansion of the Soviet Union.”

Herring (now King), recounts: “What happened in that hemisphere came to the United States and to Houston. I was invited to France because I was a niece of George Washington, and the great-great-great nephew of [Marquis de] Lafayette wanted me to meet what he thought were the five greatest strategists in the world. One of them was a Pakistani, and he became the ambassador to the United States. My husband was a prominent businessman who put Enron together-not the one who destroyed it.

“This man suggested that my husband become the honorary consul of Pakistan, because he wanted to do business with him,” King continues. “My husband declined, but he suggested, Why don’t you take Joanne?,’ which was quite a strange idea for a Muslim country. He recoiled in horror at first, but he also didn’t want to offend him, so he agreed. I thought, `What can I do for this country? They desperately need money.’ So I began to work with the very poor. Our efforts were very successful. I was appointed under [Pakistan’s] President Bhutto, and later, President Zia continued to use my services because he felt that I had done a good job; then, he began to use me as an advisor.”

With Pakistani President Zia’s permission, Herring began producing a documentary that outlined the plight of refugees from Afghanistan into Pakistan-even traveling to the secret enclaves of the Mujahideen with the film’s director, Charles Fawcett. Her mission was to show the film and raise funds and awareness in America for the refugees’ plight.

Pulling her own favors, Herring called Zia in advance of Wilson’s trip and recommended him, with the proviso, as Crile noted, “that he not be put off by Wilson’s flamboyant appearance and not pay attention to any stories of [his] decadence that diplomats might relate.”

Wilson was no stranger to the culture as he had, as a seaman in the Navy, operated in the Indian Ocean with the Pakistani Navy. “President Zia was very passionate about what was happening to his fellow Muslims,” the former congressman explains. “I could tell that he was a very fearless man. He arranged for me to have Pakistani Army helicopters and go up to the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan, very near the Khyber Pass. That was the experience that will always be seared in my memory: going through those hospitals and seeing the people, especially the children, with their hands blown off from the mines that the Soviets were dropping from helicopters.

“That was perhaps the deciding thing that made a huge difference for the next 10 or 12 years of my life,” Wilson tells. I left those hospitals determined that, as long as I had a breath in my body and was a member of Congress, that I was going to do what I could to make the Soviets pay for what they were doing, and to try to help the Afghans.”

Back in D.C., Wilson would find a kindred spirit in CIA agent Gust Avrakotos. A tough, streetwise Greek American, an anomaly in the agency then run by America’s patrician class, Avrakotos was just the man Wilson needed. As Crile wrote, “He had been recruited to be a street fighter for America, and he was proud to offer his brilliant mind and ruthless skills to the country that his father had taught him to honor above all else.”

Like Wilson, the Afghans’ spirit impressed him and, as Crile indicated, “he had taken to the Afghan program like a duck to water. There was nothing like killing communists to give him a sense of well-being.” Crile suggested, “Just like Wilson, Avrakotos had felt something stir inside him the moment he met the Afghans. They were killers, and he understood these people. They wanted revenge. He wanted revenge.”

Together, Avrakotos, Wilson and a small crew of like-minded operatives engineered an intricate plan to fund, arm and train the Mujahideen, with the help of Pakistan, Israel, Saudi Arabia and China. It didn’t hurt their mission that another CIA campaign had captured the attention of the government and the media: the Iran-Contra Affair, which was diverting much of the attention and heat that could have come Avrakotos and Wilson’s way. The partners carried on with little scrutiny.

The biggest result of their efforts was ensuring the Red Army’s march across the Freedom Bridge and out of Afghanistan in 1989. Wilson recalls that, despite the nearly impossible odds against them, the Afghan people resolutely stood up to the Soviets. He, Herring and Avrakotos saw an opportunity to fight the Soviet Union alongside them, and their plan succeeded beyond anything they could have imagined. “I was just impassioned by the resistance, and I was horrified by the obvious harsh terror tactics that the Soviets were using on these somewhat defenseless people. I dedicated myself to this cause-to increasing the amounts of money allocated to this campaign-making sure they got the right weapons and training.

“The Soviet Army was the most fearsome in the world,” Wilson continues. “It was thought to be invincible. It had terrorized the world for 50 years-the great, indomitable Red Army. And these were barefoot, illiterate tribesmen, with 303 Enfield rifles, who were successfully resisting them. It was always my thought that if we could get them something sophisticated to allow them to destroy the Soviet tanks and defend against the Soviet helicopter gunships, they conceivably could drive the Soviets from their land. Nobody believed that much except me and Gust. We made it work.”

Naturally, a covert operation is, by definition, one in which the people generating it must remain hidden in shadows. This, according to Crile, became a perilous proposition for America: “Throughout the Muslim world, the victory of the Afghans over the army of a modern superpower was seen as a transformational event. But, back home, no one seemed to be aware that something important had just taken place and that the United States had been the moving force behind it.”

Of all the adventures Wilson has had, having his story portrayed in film was most humbling for the septuagenarian. “Being involved with this movie is one of the real highlights of my life,” he concludes. “And I haven’t had a boring life. The whole process was mind-boggling for a country boy from Lufkin. Mike Nichols’ attention to detail was incredibly impressive, and to be on set and hear someone with the stature and talent of Tom Hanks saying my words and being called Charlie…well that’s something.”

As for the end of this chapter of Wilson’s story, Nichols muses, “Anyone who brought down the Soviet Union would remember it fondly, and he can take a bow. I think that’s allowed.”

Continue Reading and View the Theatrical Trailer

Charlie Wilson’s War (2007)

Directed by: Mike Nichols

Starring: Tom Hanks, Julia Roberts, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, Amy Adams, Om Puri, Jud Tylor, Nazanin Boniadi, Hilary Angelo, Cyia Batten, Emily Blunt, Daniel Eric Gold

Screenplay by: Aaron Sorkin

Production Design by: Victor Kempster

Cinematography by: Stephen Goldblatt

Film Editing by: John Bloom, Antonia Van Drimmelen

Costume Design by: Albert Wolsky

Set Decoration by: Nancy Haigh

Art Direction by: Brad Ricker

Music by: James Newton Howard

MPAA Rating: R for strong language, nudity/sexual content and some drug use.

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Release Date: December 21, 2007

Views: 102