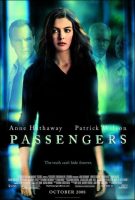

Passengers Movie Trailer. “Everyone” included Patrick Wilson, Dianne Wiest, Clea DuVall, David Morse, and Andre Braugher. Wilson, raves producer Julie Lynn, is “an incredibly versatile actor,” an “adventurer” who “brings a great sense of fun to the character.” Morse is “astonishing,” “a revelation” whose depth “you can’t fully appreciate until you see him work. It’s as if he absorbs the demeanor and the objective of any character that he plays and puts them through his body, and then it just emanates from him as beautiful work.” And Braugher, concludes Lynn, is “so warm and smart you just want to spend your whole day with him. So why wouldn’t Claire?”

With DuVall and Wiest, Garcia drew upon his past relationships with them to lure them onto Passengers. DuVall and Garcia had worked together on Fathers and Sons and Carnivàle, and, while the role of Shannon already existed in Ronnie Christensen’s original script, Garcia “rewrote parts of the character with Clea in mind,” he says. “She’s a very good actor. She’s so natural you feel she isn’t working at all; it just flows from her. But she works very hard, prepares very rigorously.”

Meanwhile, Wiest was working with Garcia on In Treatment, Garcia’s HBO special, but here the director was a little shy about asking a great actor to take such a small role, admits producer Julie Lynn. “He said, ‘She collects Oscars the way I collect hot dogs.’ But all of us, Keri and myself and the casting directors, we said no, let’s get her if we can, let her make the choice. And Dianne said yes.”

Garcia is glad he took their advice. “Diane really brought that role to a completely different level,” he says enthusiastically. “It’s not a role that has many scenes but she really took off with it and made it very funny.”

While the film was being cast, Garcia and the producers headed north to Vancouver, Canada, to begin preproduction. It was winter, cold and rainy, and though the decision to shoot north was a financial one, says producer Keri Selig, “I’m actually really glad we did. Our movie is very gray and rainy so the weather really enhanced the film. Yes, it may have been cold sometimes, but that was the look we were going for. So we lucked out by shooting here.”

Director of Photography Igor Jadue-Lillo laughs when he hears others complaining about the cold and rain. “Everyone was panicking about the weather but I thought the weather was a great, great tool on this movie. We had all these incredible, dramatic skies, and this fantastic light outdoors. Every time it started to rain I was so happy; it just helped out immensely to build this world.”

One thing that set this production apart from so many that have shot in Vancouver was the decision not to hide the city or play it as something else. “When I first came here,” says Garcia, “I said, ‘Why don’t you ever see the city?’ They’re always shooting Vancouver for something else. So I encouraged David Brisbin, our production designer, to show off the city. We don’t call it Vancouver; it’s just where the movie happens. David did a beautiful job creating this world that he called ‘ethereal Vancouver’”—a color scheme of sea green and blue inspired by the surroundings—“lit and designed in a classical thriller way with a very narrow color palette and moody lighting.”

“David Brisbin did an extraordinary job,” adds Lynn. “He takes such care. The minutest little creature sitting in Eric‘s apartment, or the large hull of the downed airplane, it’s all so important to him. And David is interested in how his design serves the movie, not how the movie serves his design. That’s a wonderful thing to have in a production designer. I can’t stress it enough. He’s a great collaborator, a real artist, and a gentleman.”

Highlighting assets, bringing them to the fore instead of treading them into submission, was also the theme on set. “Some directors,” says David Morse, “are the general in command of this huge ship and they feel it all happens by their force of will. They sometimes abuse people in order to get things done. They do good work, and many of them I’d like to work with again, but it’s not always pleasant to be on those films. With Rodrigo there’s no sense of that at all. It’s all of us making this together. He doesn’t make anybody do anything; everybody adores him so they want to do it for him. It’s just a creative environment.”

Producer Julie Lynn, who has worked with Rodrigo on several projects, observes that “what makes Rodrigo a good director is that he’s open to collaboration without giving up his own vision. He asks people to bring a lot to the table; he’s not afraid of new ideas and often will say ‘surprise me.’ But by the same token he’s very confident; people feel very safe and protected. To have someone who’s open to collaboration and yet also has a very determined vision is a great combination. It makes it a pleasure to come to work.”

With only a forty-day shooting schedule, such collaboration and cooperation were essential. “It was a challenge,” admits DOP Igor Jadue-Iillo. “I was shooting non-stop. But I have to say, production wise, whatever we needed we got. We got the cranes, the boats, the pier rigging, and we got there in very good shape. I had two fantastic camera operators, Jim Van Dyke and Gary Viola, and a great gaffer, Drew Davidson—they pushed really hard to have everything ready. The camera department maintained excellent, high standards, and the same with the electrics and the grips. There were no delays. It was absolutely amazing. I couldn’t have been happier. We were lucky to find an amazing crew.”

Where the crew really pulled through most, however, was in the creation and shooting of the movie’s two main special effects sequences, the plane’s descent into chaos and Eric’s meltdown amidst passing trains. For these Garcia relied heavily on the trio of production designer David Brisbin, special effects coordinator Jak Osmond, and visual effects supervisor Doug Oddy of Vancouver’s Technicolor Creative Services.

The crash sequence, which follows the plane from the explosion at high altitude to the moment of impact on the beach, was a complex mix of live shots and computer animation. “We were on set with about a 180 degree wraparound green screen and various stages of plane dressing for the interior fuselage as it tears open, right down to the crash landing on the beach,” explains Doug Oddy. “We probably shot at least a day’s worth of helicopter plates for the various angles of the front of the plane, the side of the plane, the views of the windows, which we stitched together with a digital wing and a digital engine that was burning, along with a digital tear. The whole side of the plane rips open and we watch as the horizon gets closer and closer and closer. That’s one of the unique aspects of this plane crash: every single shot takes place inside the fuselage, right to the point of impact.”

For this unique perspective on the crash Oddy gives sole credit to the director. “When we’re analyzing the effects work, before we’ve had conversations with the director, we see the shots a certain way,” says Oddy. “And we tend to have a generic blueprint in our mind made up of all the different experiences we’ve had. Most of us don’t have the experience of surviving a 737 crash, so we tend to fill it in with what we do know, which is usually other films. This changed completely after talking to Rodrigo; he took it in a totally different direction. He opened it up and energized it. His vision was about the cold reality of what it must be like to carry a plane crash all the way down. In the two minutes it actually takes to lose altitude, what goes on between the people inside?”

In this respect the visual and special effects were designed to function in service of the characters and not as a spectacle in and of themselves. “We wanted the picture to look realistic, not hyper-designed,” says director Garcia. “The stuff that the passengers go through on the airplane is shocking and traumatic, but we kept the relationships between the people going through this, facing what could be their last moments, as the main focus. The idea is not to end with a bang of special effects because that’s just not the story; it’s about the people on board.”

Nevertheless, the crash did prove spectacular, especially to those in the neighbourhood who witnessed the wreckage and huge explosions—and who frantically called 911 before word got out it was a film set scattered across Vancouver’s picturesque Spanish Banks. “We had the entire fuselage of a plane broken and torched all along the beach,” laughs producer Keri Selig. “People walking and driving by thought there was a real plane crash and were freaking out. We alerted the media, talked to everyone, put signs everywhere. And then it turned into this extraordinary day. Everyone from the neighborhood came with their kids and cameras. It felt like we were shooting this with the entire city. Everyone welcomed us.”

The other major scenario for the production team was Eric’s meltdown in the train yard, another complex shot integrating live footage and computer animation. The scene, where Eric stands between two fast-moving trains traveling in opposite directions, was too dangerous to shoot entirely live and also, says, Doug Oddy, “technically difficult to control. The scene called for up to four or five tracks; that’s a fairly busy section of any rail yard. To control the shoot is difficult because so many things are scheduled with those trains, and the location itself is a difficult and dangerous place to shoot because obviously trains are hard to stop—if you have a film crew with cables all over the ground, we’re not the quickest getting out of the way. That, and putting an actor in front of a moving train is maybe something you want to avoid.

“So it was determined that we would help with digital trains. We combined a little bit of green screen work, a whole lot of practical interactive lighting effects for the light that would have been cast by moving trains, combined that with some special effects help—interactive wind and debris for passing trains—and put together a sequence that worked very well. Basically, it involved two moving trains and one static train with Eric standing on the tracks. We shot a series of locked off plates from passes with Eric against a green screen with interactive lighting just on him. Then two background passes with interactive lighting as the grips moved a dolly along the tracks that had lights at the same positions as a train would have.

“We then took multiple exposures of the environment so we would be able to paint backlight for anything that was missed. We cut all those pieces up, built the digital trains, tracked them into the shot, added a little camera movement back in, and we had our finished sequence.”

Oddy makes what was a hugely difficult task seem easy, perhaps because it wasn’t the film’s major effects scenes that excited him the most as the subtle nuances the visual and special effects teams brought to the story. “Some of the effects are rather subtle,” says Oddy, “the development of mood or to help sell an emotion that you’re otherwise not really cognizant of. This is a film where after you’ve seen it once you notice completely different aspects of the film the second time through. And the story has a twist to it. You think you’re seeing one thing but you’re really seeing a reflection of another reality. Being part of that subtle trick is what we embraced the most.”

Passengers (2008)

Directed by: Rodrigo Garcia

Starring: Anne Hathaway, Patrick Wilson, Chelah Horsdal, Ryan Robbins, Andrew Wheeler, Robert Gauvin, David Morse, Clea DuVall, Dianne Wiest, Chelah Horsdal, Karen Elizabeth Austin, Stacy Grant

Screenplay by: Ronnie Christensen

Production Design by: David Brisbin

Cinematography by: Igor Jadue-Lillo

Film Editing by: Thom Noble

Costume Design by: Katia Stano

Set Decoration by: Carol Lavallee

Art Direction by: Kendelle Elliott

Music by: Ed Shearmur

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for thematic elements including some scary images, sensuality.

Dstributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: October 24, 2008

Views: 137