Tagline: No one can outrun their destiny.

Apocalypto movie storyline. A Mayan forest village lives happily and harmoniously, except the mean teasing of Blunted’s inability to sire. When terrified refugees pass, the chief forbids the hunting party to ‘spead fear’, but the real cause soon follows. Their own community is pillaged, the survivors cruelly enslaved and dragged away. The chief’s proud son Jaguar Paw manages to hide his pregnant wife and toddler son, but in an unsafe place.

The men are destined for bloody sacrifice to the gods in the raider kingdom’s pestilence-stricken capital. An ‘auspicious’ solar eclipse renders their number superfluous, but the raiders’ captain orders them killed as target practice. Jaguar Paw survives, killing the captain’s son, and may now incarnate an apocalyptic prophecy or still perish without saving his family, while another danger looms unseen.

Apocalypto is a 2006 American epic adventure film directed and produced by Mel Gibson and written by Gibson and Farhad Safinia. The film features a cast of actors consisting of Rudy Youngblood, Raoul Trujillo, Mayra Sérbulo, Dalia Hernández, Ian Uriel, Gerardo Taracena, Rodolfo Palacios, Bernardo Ruiz Juarez, Ammel Rodrigo Mendoza, Ricardo Diaz Mendoza and Israel Contreras. Similar to Gibson’s earlier film The Passion of the Christ, all dialogue is in a modern approximation of the ancient language of the setting. Here, the Yucatec Maya language is used, with English and other language subtitles, which sometimes refer to the language as Mayan.

Set in pre-Columbian Yucatan and Guatemala around the year 1511, Apocalypto depicts the journey of Jaguar Paw, a Mesoamerican tribesman who must escape human sacrifice and rescue his family after the capture and destruction of his village at a time when the Mayan civilization is about to come to an end. The film was a box office success, grossing over $120 million worldwide, and received mostly positive reviews, with critics praising Gibson’s direction, Dean Semler’s cinematography, and the performances of the cast, and the portrayal of Mayan civilization was generally praised.

A Legend That Begins As a Civilization Ends

Powerful Maya kingdoms ruled in the Americas for more than 1,000 years, forging expansive cities, constructing sky-piercing pyramids and building an impressively advanced society of extraordinary cultural and scientific achievement. Then, in a flash of history, this world collapsed. All that was left behind were a few jungle-covered pyramids and a tantalizing mystery. Now, 500 years after the end of the Mayan civilization, director Mel Gibson delves into this never-explored realm to create a modern screen adventure which unfolds like a timeless myth about one man’s quest to save that which matters to him the most in a world on the brink of destruction: APOCALYPTO.

As a filmmaker, Gibson has always been drawn to the biggest, boldest and most enduring of stories. Though he began his career as a charismatic screen idol in films such as the iconic action thriller “Mad Max,” the hugely popular “Lethal Weapon” series and the recent blockbuster “Signs,” he has become just as well known as a major American director with a penchant for intense storytelling. His second feature film was the exhilarating epic “Braveheart,” which mixed history, romance, graphic action and drama to unfold the inner and outer battles of the legendary Scottish hero William Wallace. The film would receive ten Academy Award nominations and win five Oscars®, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Following on the heels of that success, Gibson took another daring turn. His third work as a director was “The Passion of the Christ,” an exploration of the final 12 hours of Jesus Christ’s life in a film that revisited this eternal story with the uncompromising realism and raw emotion of contemporary cinema. The film was an unprecedented worldwide success and changed the face of Hollywood.

But few could have imagined where Gibson would turn next—to one of the most mysterious and alluring civilizations in all of history, where he would set a nonstop, constantly accelerating thriller, driven by visuals and pure emotion, forging an original film experience truly unlike any other.

The inspiration for APOCALYPTO came following “The Passion of the Christ,” as Gibson began to sense a growing hunger among film audiences for movies that would be thrilling and entertaining, but also something more. “I think people really want to see big stories that say something to them emotionally and touch them spiritually,” Gibson says. Fascinated by the precipitous collapse of the ancient Mayan civilization, Gibson imagined setting such a story inside this mystery-laden culture.

To begin with, Gibson knew only that he wanted to create an incomparable chase film in which a man must put everything on the line. “I wanted to make a high-velocity action-adventure chase film that keeps on turning the screws,” recalls Gibson. “I was intrigued by the idea that most of the story would be told visually—hitting the audience on the most visceral and emotional of levels.”

But as Gibson shared his ideas with screenwriter and graduate of Cambridge University Farhad Safinia, they began to explore the seemingly wild notion of setting this epic tale of action at the end of the reign of the Maya. Safinia, who had traveled in the Yucatan and seen Mayan ruins firsthand, intrigued Gibson with his stories, and the script began flowing from there. “The idea was like this fantastic engine,” Safinia says. “The story was always driving, driving towards something, and it was thrilling even as we were writing it. There are a lot of revelations, plot twists and developments that happen at high speed.”

As they wrote, Gibson and Safinia immersed themselves in the fascinating history of the Maya. They spent months reading Mayan myths of creation and destruction, including the sacred texts of prophesy known as the Popul Vuh. They pored through the latest archeological texts about new digs and theories about the civilization’s collapse. Then, they made their own firsthand journeys to view ancient Mayan sites for themselves, which had an especially profound effect.

Recalls Gibson: “I stood on top of the temple at El Mirador in Guatemala, in the only rainforest left in the country, and looking out, I could see the outlines of 26 other cities—all around us like a clock. You could see pyramids popping out of the jungle in the distance. It was quite something. You really got the sense of how powerful a civilization this once was.”

Gibson and Safinia also had long conversations with Dr. Richard D. Hansen, a world-renowned archeologist and expert on the Maya, who served as a consultant on the film. “Richard’s enthusiasm for what he does is infectious. He was able to reassure us and make us feel secure that what we were writing had some authenticity as well as imagination,” says Gibson.

It was Hansen who helped Gibson and Safinia uncover some of the secrets of the Maya that most intrigued them—and especially to get a grip on how such an amazing society could fall to pieces. Hansen confirmed what Gibson and Safinia had intuited: that there are provocative parallels between the end of Mayan society and the contemporary chaos of our own.

“We really wanted to know—what were the reasons behind the Mayan cycles of rise and collapse?” notes Safinia. “We discovered that what archeologists and anthropologists believe is that the daunting problems faced by the Maya are extraordinarily similar to those faced today by our own civilization, especially when it comes to widespread environmental degradation, excessive consumption and political corruption.”

Adds Gibson: “Throughout history, precursors to the fall of a civilization have always been the same, and one of the things that just kept coming up as we were writing is that many of the things that happened right before the fall of the Mayan civilization are occurring in our society now. It was important for me to make that parallel because you see these cycles repeating themselves over and over again. People think that modern man is so enlightened, but we’re susceptible to the same forces—and we are also capable of the same heroism and transcendence.”

The deeper Gibson and Safinia probed into Mayan culture, the more they were able to fully develop their lead character—Jaguar Paw. Jaguar Paw’s story, that of an ordinary man who is pushed into heroic actions, is at the very heart of APOCALYPTO. As the movie begins, he is a young father, promising, instinctively aware but not quite yet a leader in his small, idyllic village of traditional hunters. Then, in one breathless moment, his entire world is ripped apart when he is captured and taken on a perilous march through the forest to the great Mayan city, where he learns he will be sacrificed to the gods to “pay” for the widespread famine that has ravaged their realm. Facing imminent death, Jaguar Paw must conquer his greatest fears as he makes an adrenaline-soaked, heart-racing dash to try to save all that he holds dear.

Throughout his stunning journey, the camera never leaves him, revealing everything he sees, feels and experiences. Despite the fact that the character lived in a mysterious culture centuries ago, Jaguar Paw’s moving coming-of-age story and his increasingly courageous fight to save his family felt deeply contemporary to the screenwriters. “Jaguar Paw’s story is one that anyone will relate to,” notes Gibson. “In the course of his journey, he has to put his own self aside and fight for something much larger.”

Part of what makes Jaguar Paw’s battle so epic is the sheer enormity of what he is fighting. “The key villain in the film is really not a person,” says Gibson. “It’s a concept, and that concept is fear. The hero has to overcome his fear, and being overtaken with fear is something we all have struggled with in history as well as in today’s world, so it’s something everyone relates to.”

For Gibson and Safinia, the underlying themes of man’s struggle to live in balance with nature, of corrupted societies, of familial love and of sacrifice for others became a foundation for building sheer excitement as Jaguar Paw makes his way through a gauntlet of both human and wild threats. They hoped to create a story that moves so fast, that cuts so closely to the bone, that the full impact of its themes would only hit audiences later. “I think the first thing that strikes you about this story is the great adventure of it and the incredible kinetic impact,” Gibson says, “but beneath that are the underpinnings of all that has set Jaguar Paw’s journey in motion.”

Relentless motion and starkly visual storytelling lie at the very core of APOCALYPTO’s creative concept. “ “From the minute the story gets going, almost everything you see on the screen is in motion,” Gibson explains. “In every frame, the camera is always moving and there’s always someone or something moving within that moving shot.”

Once he and Safinia completed the screenplay, all the dialogue was translated into the Yucatec language, the primary Mayan dialect spoken in the Yucatan peninsula today. Gibson felt that the effect would be to pull the audience completely into this world—just as it had done when he used authentic languages for “The Passion of the Christ.”

“I think hearing a different language allows the audience to completely suspend their own reality and get drawn into the world of the film,” Gibson summarizes. “And more importantly, this also puts the emphasis on the cinematic visuals, which are a kind of universal language of the heart.”

Casting Maya in The Modern World

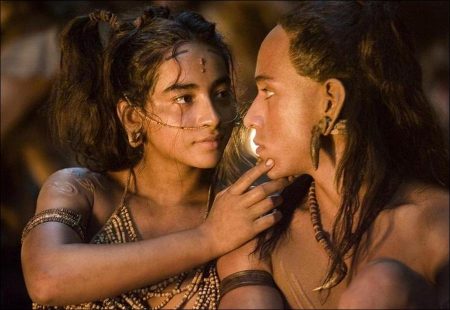

If Gibson’s vision for APOCALYPTO was going to come to life, the director knew he would need actors who would make the story feel completely and utterly real, as if it were dynamically unfolding in the here and now. He was determined from the start to use only faces that were authentically indigenous to tell this indigenous story—and to cast actors who would be completely unknown to moviegoing audiences. “It makes the story feel that much more real and convincing, because you don’t have any reference points for the performances you’re watching,” comments Gibson. “But this doesn’t mean you won’t see amazing performances, because you will.”

To capture a consistent Mesoamerican look in each of his actors, the filmmakers cast an unusually wide net, going on extensive searches throughout Mexico, especially in the Yucatan, Mexico City, Oaxaca, Xalapa, Veracruz and Catemaco. The quest continued in Southern California and New Mexico; in Edmonton, Calgary, Toronto and Vancouver; as well as Central America. Ultimately, three cast members hailed from Canada, two from the United States, and the remainder came from Mexico and other parts of Central America, including over 700 extras who create the sense of a teeming metropolis of many classes and backgrounds in the Maya City sequences. Some of the younger cast who came from isolated Indian communities had never even seen a hotel room before the production.

“Many of our cast had never been in a film before,” says Gibson, “but that worked because what we really wanted to capture were the primal instincts and natural reactions that to me are the most heartfelt and emotionally real. I wanted everything to feel authentic and believable.”

Gibson hired Carla Hool, a Mexico City-based casting agent, to help with the auditions, which involved an unusual process. “The actors had to be really physically fit, with bodies like athletes or dancers, and have great stamina,” she explains. “In fact, part of our casting process was seeing how the actors could move and run. We also had them read Mayan poetry. We were not necessarily looking for people with a background in acting, although we do have a number of fine actors in the cast. But they didn’t have to act per se. It was more about their look, their movements and what they had within them.”

For the lead role of Jaguar Paw, Gibson knew he would need an actor who the audience would follow through this unremitting journey of unexpected battles, shocks and revelations. After extensive auditions, he discovered Rudy Youngblood, a Native American of the Comanche, Cree and Yaqui people, who makes a riveting acting debut in APOCALYPTO. A powwow dancer, singer and artist, Youngblood also is an accomplished athlete, cross-country racer and boxer—and his physical vibrancy along with his natural expressiveness made him perfect for the role of a man racing to save his life, his loved ones and the forest that has always been his home.

“Rudy has an innocence but also an incredible strength,” says Safinia. Adds Gibson: “I’m so proud of what he was able to achieve.”

Despite the fact that Jaguar Paw lives within an ancient culture, Youngblood immediately related to him. “Jaguar Paw is a lot like me,” he says. “We’re from different eras but very much the same person. He is strong. He’s a giver, not a taker. He loves his family. He’s respectful, and he learns in the course of the story not to be afraid. This is also what I have been taught in my culture.”

Youngblood’s physical prowess and honed athleticism enabled him to do most of his own stunt work, including a scene that simulates a death-defying free-fall from the top of a raging waterfall, as well as the breathtaking sequence in which Jaguar Paw is chased by a jaguar— which involved Rudy getting up close and personal with a really big cat. “Rudy is probably the purest athlete I’ve ever seen,” comments Mic Rodgers, stunt coordinator on APOCALYPTO. “He has his head together and is totally on top of his game. If he wasn’t an actor, he could be a stuntman.”

Says Youngblood: “The physicality of this film was gut-wrenching and some of the scenes—jumping off the waterfall and being chased by the jaguar—were literally heart-pounding for me. There was constant adrenaline, constant action, and lots of pain and fear, but Jaguar Paw is able to transcend all of that. It’s part of who he is.”

Meanwhile for the role of Zero Wolf, the fierce Holcane warrior who captures and then must hunt down Jaguar Paw, Gibson cast Raoul Trujillo, a native of New Mexico who is an established actor in film and television (“Black Robe,” “The New World”) as well as a dancer and choreographer. It was Trujillo’s intense focus and leadership qualities—along with a more vulnerable, paternal side—that convinced Gibson he could pull off a role that goes beyond the typical black-and-white contours of a villain.

Trujillo’s transformation became complete when he donned the complex makeup that turned him into Zero Wolf. “He’s actually a very handsome guy, so we had to ugly him up some!” remarks Gibson. “We marred his natural features and gave him a more mythic proboscis. He became very scary looking.”

Trujillo picks up the story: “At our first meeting, Mel said to me, ‘You are Zero Wolf’ and at that time, I really didn’t know who Zero Wolf was. But when I put on the costume and makeup, I truly did become Zero Wolf. It was like Mel said, ‘You don’t have to be scary. You are scary.’”

Yet in playing Zero Wolf, Trujillo wanted to emphasize that the character isn’t necessarily evil. “Zero Wolf is a character who has a timelessness, who has existed in all cultures, within all of humanity,” he says. “He represents the shadow of the hero of the film. He drags Jaguar Paw through all the paces necessary to become who he needs to be to present hope for humanity and a future. I wanted him to have the complexity of being someone who has a job to do and does it. I really invested energy into developing a character that was not rooted or based in evil but rooted in the fact that he is just carrying out his duty.”

Many of the other key characters in APOCALYPTO are played by newcomers who impressed the filmmakers with their unique combinations of classical looks and colorful personalities. For example, in the role of insidiously impatient Holcane Warrior Snake Ink is Rodolfo Palacios, an actor from Mexico City, who was cast because of his unique ability to look threatening in a fresh way. Palacios endured 7 hours in the makeup chair every day to sport the complex web of facial and torso tattoos that make Snake Ink so uniquely frightening. It wasn’t easy, but Palacios was always impressed by how generous Gibson was with his diverse and largely inexperienced cast. “He was always talking with us about our opinions on the script, our characters, the whole process. It was very special,” says Palacios.

To portray another terrifying warrior, the fierce and imposing warrior Middle Eye, veteran Mexican actor Gerardo Taracena joined the cast. “Middle Eye is an absolutely insane character and Gerardo has a great look and is a wonderful actor,” says casting director Carla Hool of the choice.

One of the film’s more humorous characters, Jaguar Paw’s fellow villager and bane of many village jokes, is Blunted. He is played by another new discovery: Jonathan Brewer, who hails from the Blood Reserve in Canada, where he acts and also teaches his culture to inner-city schoolchildren. It was Brewer’s impressive size yet gentle spirit that drew Gibson to him for the role. Brewer wanted to bring the sense of a real human being beneath the comic relief his character provides. “I read the script numerous times to figure out who Blunted really is and talked to Mel and the other actors about him. The character you see on screen grew from all of that,” says the actor. “He’s someone we all can relate to—the big, gentle guy who always gets picked on.”

In the role of the powerful High Priest of the Maya City is Fernando Hernandez, who is himself a Maya originally from Chiapas, Mexico, and who currently lives in Canada, where he conducts indigenous healing ceremonies. Hernandez also appears this year in Darren Aronofsky’s “The Fountain.” As a Maya, he felt especially close to the film’s larger themes. “I believe that to stay in balance is important, and the movie shows what happens when imbalance takes hold,” he says. “As human beings, we always have the responsibility to try to create a society that restores balance.”

Additional Mayan actors in the film include the Old Storyteller who entertains the village with vital myths and tales by firelight. To play this brief but haunting role, Gibson chose an actual Maya storyteller who was discovered in a tiny village in the Yucatan.

Many of the actors were found by serendipity. The character of Monkey Jaw is played by Carlos Ramos—an immigrant from El Salvador who worked at a juice car in Santa Monica before he was discovered dancing at the Third Street Promenade. Another inspirational find came when the filmmakers first saw the stunning visage of Dalia Hernandez, a dancer and student in Veracruz, whose movingly classic features made her the very picture of Jaguar’s beautiful and enterprising wife, Seven. Others cast in APOCALYPTO emerged from such diverse non-acting backgrounds as dancers, mimes, acrobats and gymnasts, circus performers, stage and street theater actors and musicians, as well as a television production assistant and even a primary-education teacher from Cancun.

Yet no matter where the cast members hailed from or what previous experience they had, Gibson wanted all of that to be erased as they immersed themselves completely in the reality of the Mayan world of the film.

“What’s amazing is that Mel has basically created this epic movie with nonprofessional actors, most of whom have never been in front of a camera,” says executive producer Ned Dowd. “He was patient, caring and detailed to the point that many times, he was acting out the scenes for and with the actors. It was remarkable to see how committed he was to this cast, tirelessly devoting his time and energy not only to the main actors but also to the extras, to help them understand and find that special something within them that defines their character.”

One Language Unites The Multinational Cast

As APOCALYPTO got under way, Mel Gibson faced an extraordinary set of challenges. Not only was he working with a cast of newcomers and nonprofessional actors, many of whom spoke different mother tongues, but he wanted that entire international cast to speak in Yucatec Maya for the film. Though Yucatec Maya is the language spoken today in the Yucatan Peninsula, few people outside of that area have ever even heard it being spoken, let alone spoken it.

Although the film puts the emphasis on powerful visuals over the use of dialogue, for the actors, getting the language right was a big part of forging authentic performances. Says Rudy Youngblood: “It’s an issue of respect, because we’re not just depicting characters, but a people’s entire way of life, its way of speaking and its way of carrying themselves. So the understanding of the culture and the language was very important to us.”

Native Yucatec speakers trained the actors for five weeks on the correct pronunciation and inflection of their lines, which was challenging for everyone. Says Jonathan Brewer, who plays Blunted: “It’s a pretty tough language to learn because you’ve got all these pops and clicks you make with your mouth and tongue. It’s also one thing to learn to speak it and another thing to speak it wearing false teeth!”

To further assist in the process, each actor was given an MP3 player so they could continually listen to their dialogue lines until the language felt familiar. During production, the dialogue coaches were on set every day to verify pronunciation and make whatever corrections were needed. In cases where the filmmakers needed additional lines or if dialogue changes were made, they would provide Gibson with the correct phrasing and pronunciation of the way it actually would be spoken.

The local dialogue coaches were themselves moved by Gibson’s willingness to use their local language in a major global motion picture. “APOCALYPTO will have a great impact on my Maya brothers because of the pride and love of our culture and above all our roots, our language and our ancestors,” says Hilario Chi Canul, one of the Mayan dialogue coaches whose last name, coincidentally, means “Keeper of the Language.”

Yet for Gibson, the real impact of APOCALYPTO lies in a language that unites people around the world: the language of the visual, with its impact going far beyond words.

Journey Into The Jungle

Before he set off for the jungles of Mexico, Mel Gibson had a strong vision of what he hoped to accomplish there—and it was nothing less than a time-machine effect. “I wanted the audience to feel completely a part of that time, and I didn’t want one trace of the 21st century—while at the same time, cinematically, I wanted it to have a kind of break-neck kineticism and be very up-to-the minute,” he says. “That was very difficult to do.” He knew it would require an incredibly talented, but also unusually flexible and devoted, team of craftsmen, so he assembled a crew that includes multiple veterans of epics and Oscar® winners.

To begin, the team scouted relentlessly for locations that could establish an authentic jungle atmosphere. They scoured Mexico, Guatemala and Costa Rica, but right off the bat, they faced daunting challenges. As they searched, the team was struck by just how little primary rainforest is left in the Americas. “It really smacks you between the eyes,” says Gibson. “It’s a huge shame that these forests are disappearing by the hectare by the minute. Luckily, we were ultimately able to find a very beautiful rainforest in Mexico that became our jungle.”

This thick, verdant forest with the tangled vines and towering trees so vital to the story’s action was found just outside Catemaco, Mexico. It is one of the last preserved rainforests in Mexico and is known locally simply as “La Jungla.” Meanwhile, to build the Maya City, the filmmakers settled on a vast and remote sugarcane field in Boqueron, about 45 minutes outside the city of Veracruz, where Gibson and his team would have the room to create an entire Mayan metropolis from the ground up. Using mostly regional labor, the production was especially pleased to be able to provide jobs and boost the local economies.

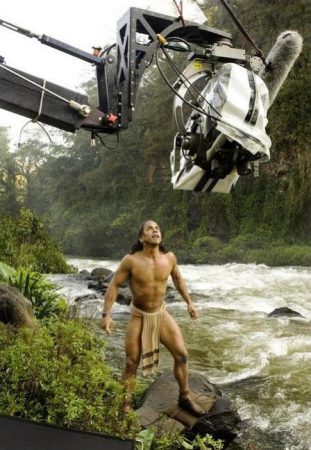

Next, to create APOCALYPTO’s high-octane look—in which the camera glides fluidly and at great velocity through the Mayan jungle—Gibson recruited cinematographer Dean Semler, an Oscar® winner for his work on the Native American epic “Dances With Wolves.” Gibson wanted someone who was willing to take daring visual risks and carry off the rapid-fire camera movements he had envisioned. “I need someone who could execute my ideas as well as bring their own,” he says.

After intensive discussions, Gibson and Semler decided they would shoot APOCALYPTO digitally, using Panavision’s state-of-the-art high-definition Genesis™ camera system. Though the system was brand-new, Semler felt it could give them the enhanced mobility, versatility and especially the ability to shoot in extreme weather conditions—drenching rains, searing heat and viscous mud all awaited—they would need to pull off the story.

The Genesis™ also offered other advantages. “APOCALYPTO is about a heart-pounding chase, so we wanted to emphasize speed, which can only be enhanced by some sort of strobing effect—an effect we were able to create with the Genesis™ and its 360-degree shutter capability,” explains Semler. “It proved to be phenomenal in the chase scenes, giving us images that could not have been gotten on any other camera. It’s all there, it feels real, and it has given us a whole new heightened dimension and velocity.”

Genesis™ also gave Gibson and Semler the opportunity to use natural light sources and shoot in the near-darkness of a rainforest canopy, where the ambient light often would fall to drastically low levels by late afternoon. Furthermore, nighttime scenes could be shot with incredible detail using just the light emanating from campfires around the village. “During the campfire scenes, we looked at the monitors and the whole village was illuminated. The whole place came to life—the people, the faces, the huts and trees. I couldn’t believe it,” recalls Semler. “And because we were shooting with a slower aperture, it made the flames look languid, flickering, but almost like liquid, very smooth. It was absolutely beautiful.”

Semler was especially thrilled to be able to use long lenses at night, which gave the film’s opening action sequences a kick right from the start. “Using the long lens in that opening night scene, when you see the Holcanes running towards the camera, they are very compressed, very stacked. It’s spectacular, something you couldn’t have done on film,” he says.

Often utilizing four cameras simultaneously, shooting digitally further allowed Semler to let the camera run in long, continuous takes—sometimes for up to 20 minutes at a time— which would also have been impossible on film. On top of the camera system’s versatility, it also withstood some outrageous conditions, including hurricanes, high winds and days of 120- degree heat.

Sums up Semler: “I was able to go to places as a cinematographer on this film, I’d never gone before. The creative possibilities were truly phenomenal.”

Also facing incredible creative possibilities was production designer Tom Sanders, a twotime Academy Award nominee who previously collaborated with Gibson on his Oscar- winning film “Braveheart.” Sanders’ career has spanned numerous epic films—his designs have ranged from World War II battlefields in “Saving Private Ryan” to the fairy tale world of “Dracula”—but for APOCALYPTO, he faced the unique task of bringing fully to life a vanished world of primal villages and kingdoms of extreme opulence.

He began with extensive research into Mayan architecture and construction techniques that would have been used in an ancient Maya city, including the fortification walls, buildings, pyramids, plazas, monuments, skull racks, huts, marketplaces and merchant areas. Working closely with Dr. Richard Hansen, Sanders also studied up on Mayan tools, utensils, weapons of war (in collaboration with armourer Simon Atherton), right down to their textiles and pottery. Then, he began the enormous task of building this world from scratch. “Almost everything you see in the film, including the props, was made by hand in Mexico,” says Sanders.

For Jaguar Paw’s village, where the people live in harmony with nature, Sanders found that there was not a lot of factual data to draw from. As only the lives of Mayan nobles were written or drawn, the life of the common villager in the forest remains a mystery to this day—so here Sanders used extrapolation and imagination. “I thought it would be interesting if the village huts looked like nests in the forest. In the village, everything is very round and organic, which contrasts with the mechanical, square stone columns of the Mayan city,” he says.

The design was also influenced by the harrowing, surprise siege that sets off Jaguar Paw’s journey. “Because of the verticalness of the forest, I wanted to create structures where you could see through the walls of the houses when the village is being attacked,” Sanders notes. “We elevated the huts so you would be able to see just feet running and to get frighteningly chaotic points of view of people attacking and fleeing.”

But Sanders’ coup de grace was constructing the great Maya City in a way that gives audiences a sense of the full resplendence—but also the teetering chaos with intimations of slavery, starvation and panic—of the Mayan centers of power toward the end of their days. The mission started with an intricately detailed model. “I am a sculptor, and the way I design is to build the entire set first in a large, 14-foot, three-dimensional model,” Sanders comments. “In this way, I could see how each piece related to another, and I would see the best camera positions for how Mel envisioned it on the screen.”

He then recruited several construction teams, as well as sculptors, model makers, painters, plasterers, greens masters and over 100 local workers to turn the model into life-sized reality. Ultimately, the city would contain a remarkably diverse landscape. On the periphery is the destitute and dilapidated shantytown, leading into the middle-class sections of the town with their palm-thatched huts, and on to the commercial area where manufacturing is taking place, and finally to the marketplace where rich and poor gather to buy and sell commodities, including slaves.

After the primary construction, everything was distressed to reveal the city’s recent state of decline—right down to simulated raw sewage flowing into the polluted city canals. Terraced fields of corn and other crops were grown and then killed to add to the looming atmosphere of famine and catastrophe. “Everything we planted, we wanted dead,” says Sanders. “The theory is that we’re in the middle of a drought and that’s why they’re sacrificing human beings at such a great pace. We wanted to show the environmental damage that has led to this situation.”

The pyramids Sanders and his team built were inspired by those found in the ancient city of Tikal, which was once the largest of the Mayan cities. Although they based their designs on extensive research, the team also had to adapt the proportions to the demands of modern filmmaking. “To accommodate actors, extras, crew and cameras on top of the main pyramid, we had to scale the narrowest sections up 20% to give more space in which the action could occur,” explains Sanders.

Especially gratifying to Sanders was how moved the Mayan expert Dr. Hansen was the first time he set foot in the re-created Mayan city. Says Hansen: “They have brought the past to life in a way that has rarely been seen in the movies.”

To further bring the past to life, Gibson relied on another key team—costume designer Mayes Rubeo, hair and makeup designer Aldo Signoretti and makeup designer Vittorio Sodano, who worked in concert to craft a complete head-to-toe look for each of the film’s characters. From the scantily clad villagers—with their ear plugs and rotted teeth—to the elaborate costumes of the Mayan royalty and priests—with their patterned embroidery, elaborate shell beading, ornate headpieces and oversized jewelry—the trio had its work cut out for them.

Nearly every element of the costuming was created by hand in exquisite detail by hundreds of artists from throughout Mexico. Costume designer Mayes Rubeo, a native of Mexico City, was well prepared for the task. She had previously conducted extensive research for a never-made Mexican documentary on the ancient Maya, so she was intimately aware of Mayan fashion, from the everyday to the ceremonial. Rubeo then assembled a team of 52 people, including professors of fine arts, fashion students, embroiderers and feather artists, who individually created each piece for each character.

Rubeo focused on bringing out the surprising diversity of looks that would have been seen in a major Mayan city. “We wanted to show the complexity and variety of Mayan styles, from patterns to jewelry to headdresses and show the way different classes dressed in Maya society,” says Rubeo. “The Maya had many styles of beauty. Everyone would personalize his or her being.”

One challenge Rubeo faced was the Mayan love of jade in their jewelry, denoting power, wealth and prestige. “Because jade is so heavy and expensive, my team learned how to hand paint other materials to allow them to have the beauty of jade but be lightweight,” says Rubeo. Also impossible to come by were the prized, emerald-colored quetzal bird feathers traditionally used in the spectacular headdresses of Mayan kings. Since the quetzal bird now lingers near extinction, Rubeo found a suitable substitute in the form of more mundane, brown pheasant feathers which were individually bleached, dyed green and hand-painted for the desired effect.

When it came to textiles, Rubeo tried to use materials indigenous to the Maya, procuring patterned fabric from such modern Mayan communities as San Cristobal de las Casas in Chiapas as well as from Oaxaca where cotton is still hand loomed. “Obviously, we could not get enough of this fabric to make over 700 costumes with multiple copies of each,” says Rubeo. “So using authentic samples, I did intensive research to find reproducible fabrics that look very close to the real thing.” Using the services of a master dyer from Mexico City, the fabrics were hand dyed to match the colors that the ancient Maya would have obtained from animal, mineral and plant sources.

Enhancing Rubeo’s work and adding more intricate details was an international team of hairstylists, wig makers and makeup artists, ultimately numbering 300, from Italy, Mexico, Malta, France, England, Ireland and other countries. Their jobs ranged from applying tattoos and body paint to simulating the body markings of ritual scarification. Several of the film’s characters—including the powerful Mayan figures of the King, Queen, High Priest, Chacs, and Jade Women—were so complex in their look that they took three to four hours of preparation in the makeup chair each morning. In the case of Snake Ink, with his wild tangle of scarifications and tattoos, the complete makeup procedure lasted about seven hours. “All our tattooing was done by hand for the actors as well as the extras,” says hair and makeup designer Signoretti. “We wanted the lines of the tattoos to look just like a real tattoo artist would have done them.”

No matter what the character, perfection of the tiniest details was a necessity. “Because of the way Mel shoots, we had to have everything perfect at every angle, even for every single extra,” says makeup designer Sodano. “Mel does a lot of close-ups, and while the camera is focusing on the scene being shot, another may be focusing on one of the extras.”

The makeup artists also had to attempt to re-create some of the unusual body deformations which the Maya used as indicators of status. Every actor and extra had to don special ear spools, extended ear lobes plugged with stones or bone, which were a trademark of the ancient Maya. Since they couldn’t actually stretch the ears of the actors—as the Maya did—special ear attachments were made of a pliable silicone, then painstakingly painted to match each actor’s skin. Another common Mayan practice was the deformation of the skull. A few days after an infant was born, a board was placed on the forehead, which caused the forehead to recede into the famous Mayan head shape. To simulate this effect, many of the actors had their hairlines shaved higher up on the head and wore elongated hairpieces.

The spectacular sets and makeup—along with the digital cinematography and irreplaceable beauty and dangers of the jungle—helped to forge the intense visual reality that was so key to Gibson’s vision. “What we wanted to do with the camera, sets, makeup, costumes and performances is make everything as real and believable for the time as possible,” he says. “I think the film has an important message to convey, but if you can carry that message in a heart-stopping, thrilling way, that is so much better.”

The Heart of Apocalypto

APOCALYPTO is the first major Hollywood action-adventure to be set amidst the great Mayan civilization of Mesoamerica. But just who were the Maya? Like detectives sifting through a vast mystery, today’s archeologists are trying to come up with answers to that question from the fabled pyramids, buried cities and intriguing artifacts they left behind. For though they were once the mightiest civilization in the Americas, neither wealth, nor power, nor brilliant engineering could save the Mayans from a devastating societal collapse.

The vast Maya homeland once spanned five modern countries—Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras and El Salvador—and flourished in three distinct periods: Pre-Classic Maya, Classic Maya and Post Classic Maya, all the way from 2400 B.C. to the 15th Century A.D. We know they were an advanced society who created intricate art, mastered mathematics, forged their own writing system, had a profound understanding of astronomy and were skilled farmers, artisans and architects whose urban cities flourished in the rainforest. But we also know they engaged in brutal practices, fomented war and that their complex society devolved into violence, slavery and chaos.

To learn more about who the Maya were and why their sophisticated civilization declined and disappeared, Mel Gibson, Farhad Safinia and the entire production of APOCALYPTO worked closely with several archeologists, including one of the film’s key consultants: Dr. Richard D. Hansen, a modern-day explorer who has been excavating a massive network of 26 ancient Maya cities entombed under centuries of jungle growth in Guatemala.

For Hansen, the allure of APOCALYPTO wasn’t just the film’s visceral re-creation of what it might have felt like to live in the time of the Maya—but its exploration of how such a society of such extraordinary power self-destructed. “I felt Mel Gibson was really interested in not only the reality of this civilization but the reality of the stresses that were key to its end. It’s a story that needs to be told. If a society doesn’t learn from its history, it may be forced to repeat it,” warns Hansen.

Hansen emphasized to Gibson just how accomplished Maya society had become during the Classic period. “The fascinating thing about the Maya is they were able to develop societal complexity at a new level in the Western Hemisphere,” explains Hansen. “By the Classic period, huge cities were thriving everywhere, and a series of smaller cities scattered around them were feeding and supplying these larger cities with the commodities they needed.” Indeed, part of the key to the civilization’s longevity was their agricultural success. “The Maya cities were green cities,” notes Hansen. “They had every available resource for cultivation. They were raising corn, squash, beans, cotton, cacao and a range of tropical fruits. And when you can eat, you can focus on other things like astronomy, mathematics, music, art, warfare and government.”

At the height of the civilization, the Maya were especially focused on trying to understand time and the very meaning of life. “The cycle of time became very carefully woven and engraved into their ideology, cosmology and behavior. The cycle of life and the cycle of time began to be a pattern that was observed in the natural and spiritual world,” Hansen notes.

et coupled with their early fascination with science was a belief in superstition and the influence of invisible forces. They believed the world was ruled by powerful deities who maintained order—but only if human beings behaved properly and observed the prescribed rituals and offerings. Failure to do so, or so the high priests and kings warned, would result in vengeance from the wrathful gods in the form of disease, pestilence, crop failure, drought and other natural disasters.

Powerful Mayan priests were said to be the only people who could communicate directly to the gods, and it was they who oversaw the regular offerings to the deities. These spanned from food and ceramic idols all the way to full-scale human sacrifices in the late Post Classic period. Human beings were considered the ultimate offering and were often resorted to in the hopes of appeasing the gods in times of greatest tumult. Eventually, to procure more captives for sacrificing, the Maya engaged in increased warfare.

The sacrifices themselves were rife with ritual. The victim was stripped and painted blue then draped over an altar stone. Finally, the priest would plunge a knife made of flint or obsidian directly through the chest and pull out the still-beating heart. Yet the Maya also believed that the sacrificial victims would gain something even while giving up their lives— instant entrance to Paradise. “The Maya had a devout belief in the Underworld and life after death,” says Dr. Hansen. “They believed they were here for a purpose and they had a place to go, and that they had an opportunity to resurrect, which was very deeply rooted in their ideology.”

Gibson was fascinated by this dichotomy between the light and dark sides of the Mayan culture. “In many ways they were so sophisticated, and in other ways they were so savage,” he observes. “But one of the things that’s very interesting is that they were very clear that their society was going to rise and fall. Whether it was a self-fulfilling prophecy or not, they were just dead accurate, they knew that there was a certain amount of time, a period of about 400 to 500 years, that a society could prosper before everything just falls out from under you.”

As Mayan cities grew, the political power of the royalty and the priests was also magnified. Over time, the society appears to have become more and more obsessed with conspicuous consumption, with preserving the power of the elite, controlling resources and manipulating subservient populations through awe, humiliation and fear. The rulers constantly demanded bigger, better and more. And with all this unquestioned growth for growth’s sake came a price to pay—the ultimate demise of one of the greatest civilizations the world has known.

“We find this same story in many cultures throughout the world in history, and even today, where a degeneration of the environment and a degradation of social systems can lead to wholesale stress on a society. This type of stress is what leads to catastrophic events, tragic events in human history, and we have to learn from them,” says Dr. Hansen.

There was probably not a single, definitive cause of the final Mayan collapse. Rather, scholars and archeologists cite a number of interrelated causes, including deforestation, climactic stresses such as drought and famine, increased warfare, the spread of disease, a loss of critical trade routes and popular revolt. Each of these likely contributed to the fracturing of the society.

Deforestation is of particular interest to Dr. Hansen, who explained to the filmmakers how it might have played a major role in the annihilation of the Mayan kingdoms. He discovered that in the process of creating the lime stucco cement used to build their temples, palaces, plazas and monuments, the Maya had to create fires to heat the limestone. “It took five tons of fresh, green wood to make one ton of quick lime,” notes Hansen. “I found one pyramid in El Mirador that would have required nearly 1,600 acres of every single available tree just to cover one building with lime stucco. So, how many more acres would be used for a Maya city? Epic construction was happening in a lot of different places, creating devastation on a huge scale.”

He continues: “Once the forest’s trees were gone, clay washed into the swamps rendering the organic muck that was essential for their agriculture difficult to reach. They could no longer feed large populations, and so they couldn’t maintain scientists, priests, astronomers, soldiers and all the trappings of a complex society. Peace and tranquility had vanished.” Much of this is depicted in APOCALYPTO in stark visuals, rather than through dialogue, which reveal the desiccated fields and endless construction of the Maya City, far from the green abundance of Jaguar Paw’s jungle.

Yet even though the Mayan civilization declined and then disappeared, the Mayan people did not. There remain about four million ethnic Maya living today in Mexico and Central America. The largest group is the Yucatec, who number about 300,000 in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico. Near Chiapas, Mexico, live the Lacandon Maya, who continue to practice elements of the ancient Mayan religion and culture. Yet, ironically the Lacandon and other Maya face a modern battle against those who seek to deforest what remains of their sacred jungles. Even the jaguar, once revered as a great power among the Maya, is now endangered.

In making APOCALYPTO, Mel Gibson hoped to be unflinching in his portrait of a society heading towards its final days—but he also wanted to include another vital concept: hope. “The story of Jaguar Paw is the story of the spark of life that exists even in a culture of death,” he says. “Every ending is also a new beginning.

Apocalypto (2006)

Directed by: Mel Gibson

Starring: Rudy Youngblood, Dalia Hernandez, Jonathan Brewer, Morris Birdyellowhead, Ramirez Amilcar, Israel Contreras, María Isabel Díaz, Iazua Larios, Mayra Serbulo

Screenplay by: Mel Gibson, Farhad Safinia

Production Design by: Thomas E. Sanders

Cinematography by: Dean Semler

Film Editing by: John Wright

Costume Design by: Mayes C. Rubeo

Set Decoration by: Jay Aroesty

Art Direction by: Roberto Bonelli, Naaman Marshall, Theresa Wachter

Music by: James Horner

MPAA Rating: R for sequences of graphic violence, distrubing images.

Distributed by: Buena Vista Pictures

Release Date: December 8, 2006

Views: 146