The plot of Broken Embraces dramatizes the importance of editing, its direct relationship with the director and the fragility of the film if someone gets between the editing and the director.

Editing is in the origin of the narrative, it is the cinematic narrative, strictly speaking. I edited my first sixteen films on a moviola. So I’m paying homage to that machine, so closely linked to my cinematic biography, and to all the magnetic and photographic materials that new technology has swept from the editing rooms.

It isn’t by chance that there’s a close-up of the core of a reel rewinding frantically, and that this image dissolves to that of Mateo hurrying down the studio steps. Both movements evolve at the same rate and in the same direction. Both have the same center and it’s the same passion that drives them.

But I don’t want to be nostalgic, above all I don’t want to be paralyzed by nostalgia. I’m willing to embrace the new techniques, in the same way that Mateo embraces on the television the kiss that is so digitally enlarged it looks totally broken on the screen. It is precisely the flickering of the pixelation that makes the image so forceful.

Making of

The protagonists of “Broken Embraces” are shooting a comedy, “Girls and Suitcases”. Mateo Blanco is the director and Lena Rivero is the protagonist. Judit García is the production manager and Ernesto Martel, Lena’s lover, is the producer. Ernesto Martel Junior is in charge of the “making of” video.

Mateo falls in love with Lena from the moment he sees her, the same thing happens to Lena (although she’s living with Martel and the tycoon is madly in love with her). Years before, Judit had a love affair with Mateo and still hasn’t got over it, although that doesn’t prevent her from working with him, in fact she’s his right hand. Ernesto Martel is a broker (from the generation of the financial boom of the 80s) with lots of money and few scruples.

He isn’t a producer, but as Lena shows an inclination for Thalia’s art, he produces Mateo’s film in a desperate effort to hold on to her. Ernesto Martel’s son, named after his father, is a childish young man who likes cinema and men, in particular Mateo. Martel Senior commissions Martel Junior to make a documentary about “Girls and Suitcases”, what would now be called a “making of”, that way he can spy on Lena. His only problem isn’t moral, but technical. The first videos have got terrible sound. Martel Senior improvises and reinvents dubbing, hiring a neutral lip reader.

All these elements are typical of a comedy, but “Broken Embraces” is a drama with very dark touches, more like a 50s thriller. Although morally I detest the way Martel is using the “making of”, a mere pretext in order to control all of Lena and Mateo’s movements on and off the set, I like the idea that the “making of” is a parallel narrative to the original (the film which it reflects), an independent, furtive narrative.

I’ve always dreamed of making a film whose story is seen through a “making of”. A “Making of” reveals not only the technical secrets but also the secrets of the people responsible for cooking up and coordinating the fiction, at times embodying it. It turns those responsible for the fiction into fiction.

The ideal “making of” should strengthen and complete the original story. But it can be dangerous (all fiction is dangerous and also therapeutic, that’s why we find it irresistible), it’s a living material, moved by its own impulses which can only be tamed and transformed if you submit them to editing. Martel Senior sees the filmed material in its raw state. He projects the video tapes just as they come from his son’s camera, supervised only by the lip reading automaton.

When Lena comes into the large sitting room of the mansion and finds Ernesto Martel, with the lip reader, viewing her violent argument with Ernesto Junior, Lena becomes a duplicate of herself, the woman who from the screen confesses to Martel that she doesn’t love him. At that moment, the “making of”, produced by Martel with perverse intentions, turns against him. Lena leaves him doubly, on the screen and from the door of the sitting room, behind him. As a result of Martel’s harassment, the humiliation and pain when Lena leaves him is doubled.

Duplication (Not Duplicity)

The “double” is one of the hallmarks of “Broken Embraces”. The “double” not in the sense of a moral term (“ambiguity”, “duplicity”), but as “duplication, repetition or enlargement”.

The film begins with the image of the protagonists’ two stand-ins. Ernesto Martel Junior duplicates his father’s behavior, even though he’s the last model he would like to imitate. When his father dies, Martel Junior plans to take his revenge on his memory with a film that tells how his father crushed and destroyed him while he was alive. Even though he’s homosexual, Martel Junior got married twice, like his father. He’s got two children who hate him as much as he hates his father (in this character’s construction there are echoes of the story of Hemingway and his son Gregory who as a young boy liked the feel of silk and taffeta, and who, after drinking more than his father, hunting larger elephants than he had hunted and having had more children than the writer had, ended up having a sex change when he was almost sixty, fifteen years after the death of his famous father).

Martel Junior’s story isn’t as terrible. After his father’s death, he unconsciously continues to imitate the paternal behavior he detests so much. The male protagonist has got “two” names. When blind Mateo starts to call himself Harry Caine, he does so to escape from himself. His reality is unbearable. He can only survive by “supplanting” or “duplicating” himself.

Before the accident, Harry Caine was already a prolongation of himself. Mateo Blanco had playfully invented the pseudonym in order to sign the scripts and stories he wrote. Like many authors, fiction was a rehearsal of reality.

A director who can’t direct and who moreover has lost the woman he adored, has only got grief and despair to look forward to; if he wants to survive he’ll have to do so through imposture. Several of the characters in “Broken Embraces” work in film. I’ve always said that for me film is “representation” of reality and at times is its most faithful reflection, its “duplication”.

Even though, the moment they are finished, all films are the past, I see premonitory qualities in them. It’s a theory that appears frequently in my filmography. In “Matador”, the two protagonists go into a cinema where “Duel in the Sun” is being shown. They arrive just at the end, when Jennifer Jones fires at and in turn is gunned down by Gregory Peck, with whom she melds in (another) eternal embrace. The female lawyer and the bullfighter in “Matador” see the anticipation of their own end on the screen.

Something similar happens in “Bad Education” when Mr. Berenguer and the devilish Angel go into a cinema as an alibi in order to kill some time, while Ángel’s brother is dying, the victim of exceptionally pure heroin which both of them have given to him, the cinema is showing two thrillers “Double Identity” (by Billy Wilder)and “Thérèse Raquin”(by Marcel Carné). Both tell of crimes by lovers, similar to the one they have committed. The cinema maintains a very vivid awareness of crimes carried out by lovers who were induced to commit them. When they leave the cinema, Mr. Berenguer (the lover who has become a criminal), overwhelmed, laments: “It’s as if all the films were talking about us”.

Film and reality: Two ride together. Penélope Cruz plays “two” characters in “Broken Embraces”. placeMagdalena, a woman who is too beautiful and too poor to resist the poisoned generosity of the tycoon Ernesto Martel. And Pina, her counter-figure, the protagonist of “Girls and Suitcases”.

Girls and Suitcases

I won’t deny that “Girls and Suitcases” is freely based on “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” But it isn’t a self-homage, I hope no one interprets it like that. When I was writing the script I decided that Mateo Blanco would be filming a comedy because it is the opposite genre to the drama the protagonists are living. In that way their problems would take on greater relevance, and the efforts, for example, by Lena to achieve the light, sparkling tone that comedy demands are more obvious and pathetic.

I only needed three or four sequences of “Girls and Suitcases” to act as background to the main story and I thought the best thing was to adapt some of my own material in which I could move with total freedom. That’s why I chose “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown”.

Once we were in the penthouse of the new “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” (curiously we shot this duplication in the same corner of the studio where I filmed the original twenty years ago) I had great fun adapting myself. The experience was so inspiring I wrote and filmed more sequences than necessary. I couldn’t include them in the final edit because their tone is the opposite to that of the general narrative and they’d be disconcerting. I’d imagined as much when we were filming them but I couldn’t resist the temptation. Fortunately there’ll be the DVD and they’ll be included in it as additional material.

In this new version of “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” Pina isn’t an adaptation of the role played by Carmen Maura, but rather of the role of her model friend Candela. The character also has echoes of Holly Golightly from “Breakfast at Tiffany’s”, the most modern ingénue of cinema and American literature, although the hairstyle is that of another character played by Audrey Hepburn, Sabrina.

Noir

When Lena falls into Ernesto Martel’s clutches she has all the attributes of the “femme fatale”, dark, ambitious beauty, a humble past and a family in a precarious situation, the intelligence not to resign herself and to take risks; but she has too many scruples and she lacks cynicism. Her love for Mateo precipitates her tragedy, even though she would have eventually left the tycoon and he wouldn’t have allowed it.

Lena isn’t a “femme fatale”, she’s condemned to misfortune. Mateo, Lena and Ernesto Senior make up a typical “noir” trio. The three love fiercely and one is very powerful, violent and unscrupulous. Combustion is served. The trio is flanked by Judit García, who brings treachery, a secret son and a guilt complex to the group, ingredients that will make the relationship between the four even thicker.

Film “noir” is one of my favourite genres. I’d already moved in that direction in “Live Flesh” and “Bad Education” and I’ve done so again in “Broken Embraces”.

The scene of Ernesto Senior’s feet, walking up to and then away from the door of the room where Lena is, followed by the scene on the staircase are definitely “noir”.

After an hour’s narrative, the scene on the staircase reveals the genre to which the film belongs, and that sensation of blackness doesn’t leave us until the end.

Up and Down

The staircase is a real cinematic icon. It suggests the idea of displacement, and movement is what differentiates cinema from photography. I remember the staircase which the pregnant Gene Tierney throws herself down in “Leave Her to Heaven” (John M. Stahl), along with “Él”, by Luis Buñuel, the best film about the madness of jealousy.

I remember Richard Widmark tying a paralytic woman to her wheelchair with a telephone wire and pushing her from the top of a staircase because the woman refused to reveal her son’s whereabouts, in “Kiss of Death”, by Henry Hathaway. A horrifying thriller and a horrifying Richard Widmark.

The steps in “Battleship Potemkin” by Eisenstein are the mother of all steps, undoubtedly, the most impressive scene with steps that cinema has ever given us. Brian de Palma’s tribute in “The Untouchables” is also memorable.

And the operatic grandeur of the final scene of “The Godfather, Part III” or the great red staircase on which Vivien Leigh loses her baby in “Gone with the Wind”. Or Norman Bates and Baby Jane (Anthony Perkins and Bette Davis in “Psycho” and “What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, respectively) two deadly characters if you meet them at the top of a staircase.

Gothic terror, epic drama and the thriller are genres that have made the most of staircases. But so have the crazy comedy and the musical. I remember a number in Busby Berkeley’s “Ziegfeld’s Girl” that consisted exclusively of a group of young ladies, among whom were Lana Turner and Hedy Lamarr, coming down endless, winding stairs, while placed inside enormous costumes.

Without intending to compare myself with all the above, I feel very proud of the staircase scene in “Broken Embraces”, a sequence that is the backbone of the narrative.

The Photo

Once again duplicity. In Lanzarote, Lena and Mateo are looking at the impressive Golfo Beach. Mateo is taking photos, while Lena embraces him from behind. They don’t see them, but down below, on the beach of black sand, an embracing couple mirrors them.

Mateo discovers them when he prints the photo (the eye of the camera sees farther than the human eye) and pins it on the wall of the bungalow where they have taken refuge. The photo reflects Mateo and Lena’s situation better than any other image does. They are fugitives, alone in the immensity of the volcanic island, melding one with the other, blending into the landscape, like the couple in the photo.

I had taken the photo which we used nine years ago, on my first visit to Lanzarote. The island had bewitched me. I’d never seen such dramatic colors in nature. For me it wasn’t a landscape, it was a mood, a character. From that moment I wanted to film there.

My first visit to Lanzarote occurred at a very special moment. My mother had died a few months before. My spirits, still in mourning, found reflection and consolation in the blackness of the island, a kind of soothing energy. I was more aware that my mother’s death had made me into an adult.

Just as in my youth I’d been trapped by the technicolors of the Caribbean, my trip to Lanzarote first developed my fascination for black and the more somber semitones of red, green, brown and grey. As confirmation of the island’s mystery, I took the photo on Golfo Beach. Like Mateo, I hadn’t seen the couple embracing at the bottom of the photo. I discovered them when a 24-hour developing store gave me the print. The landscape was incredible but what really struck me was the discovery of the couple embracing, alone, minute against the immensity of the landscape.

Obsessed as I am with my work, (thinking perhaps about the photo taken in the London park in “Blow Up” which, when enlarged, revealed a body hidden in the bushes) I imagined that there was a secret behind that furtive embrace and that I had the photographic evidence of it. I wanted to know everything about the couple, or at least some detail with which to spin a fictional story.

I looked for the couple during the remainder of my stay on Lanzarote, but I couldn’t find them. I imagined their situation and I wrote various fictional options that ended with the solitary embrace, but none of them was of interest.

I went back to Lanzarote and searched again in its volcanic landscape for a story that would include the embrace on Golfo Beach, without finding anything that satisfied me. The secret of the embrace was reluctant to reveal itself. I still had the island, as a setting. I tried to introduce it into all the scripts I wrote from then on but I didn’t find the story that could include it until 2007-2008, when I finished the script of “Broken Embraces”.

Lanzarote would be the island where Lena and Mateo hid, Famara their refuge, their Pompeii, and the roundabout their Vesuvius. They were the couple on Golfo Beach, as Lena tells Mateo while she cuts and peels fruit in the kitchen of the bungalow in Famara.

Parents and Children: The Monologue

One of the important themes in the film is the relationship between parents and children, maternity and paternity. The family, in short.

The monologue of “The anthropophagous councilwoman”, which will also appear on the DVD as a short, is the child of “Girls and Suitcases”. We could say it’s a spin off of Carmen Machi’s brief but hilarious character.

I didn’t film it in order to include it in “Broken Embraces”, although it complements the film, but once it was written, and even though I didn’t have time, I shot it in one day. It was a prank, a whim and a liberation, something I’ve committed in other stages of my life and which I hadn’t allowed myself to do for a long time.

In the monologue about the erotic fantasies of a councilwoman for social affairs I recover that free, playful, very politically incorrect, irrepressible, crude tone of the “Patty Diphusa” of the early 80s. I confess that it was a refreshing, liberating experience, and an enormous pleasure to see how the great Carmen Machi performed it. I was also delighted to see that that tone is still there, that it hasn’t disappeared with maturity, the grey hair and the headaches.

Declaration of Love

Cinema plays a very important role in all my films. I don’t do it as a pupil revering those directors who have preceded him. I don’t make films “in the style of”. When a director or a film appears in one of mine, it’s in a more active way than as a simple homage or a nod at the spectator.

I could give a lot of examples. When in “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” Carmen Maura has to dub a sequence of “Johnny Guitar”, I’m not paying tribute to Joan Crawford or Sterling Hayden or even to Nicholas Ray, one of my essential directors. I’m using his marvellous, heart-rending love scene (“Lie to me and tell me that you still love me the way I love you”) in order to accentuate the loneliness and abandonment of THE character. Carmen (Pepa) is a dubbing actress, so is her lover Iván.

That morning he isn’t with her, dubbing Sterling Hayden as he was supposed to, because they’ve broken up and he is avoiding her. Iván went to the studio before she did so as not to meet her, and he dubbed his part alone, on a separate soundtrack. Pepa has to listen to his voice over the headphones and slot in her replies. She will never again hear words of love directly from Iván’s lips, she can only listen to them over the headphones, in a recording studio. Her loneliness and abandonment are more obvious through the famous scene from “Johnny Guitar”. At times, the best way I can transmit a character’s feelings is by doing so through cinema, using words that another author wrote before I did.

In “High Heels”, Victoria Abril and Marisa Paredes talk in a courtroom in the Supreme Court. Marisa, the mother and star, is horrified and can’t understand why her daughter has accused herself publicly (on the TV news program which she presents) of the murder of her husband, who was also her mother’s lover. In order to explain how she has felt about her mother since she was a little girl, Victoria tells her a scene from “Autumn Sonata”, in which Liv Ullman has an unusual visit from her mother, a famous pianist, and she plays a sonata to flatter her and in her honor.

The mother (Ingrid Bergman) thanks her unenthusiastically and then sits down at the piano and explains how that sonata should really be played. And that demonstration is the greatest humiliation the mother can inflict on her subdued, insignificant daughter. I could have said it was a homage to Bergman, one of my five key directors, but that isn’t so (my great excitement about the stage version of “All about my mother” opening in Stockholm has got nothing to do with my vanity, but with that fact that it’s performed in the same language that Bergman spoke). When Victoria Abril recounts the scene to Marisa Paredes she feels as insignificant and humiliated as Liv Ullmann. In the end she admits that she accused herself publicly on television of having murdered her husband, not just to cover up for her mother, who had killed him, but to get her attention. To tell her, with such an excessive gesture, how much she loved her.

In “Broken Embraces” I also use the transparent simplicity of Rossellini’s “Voyage to country-regionItaly” to show the effect on Lena-Penélope of the discovery of the couple burned to death in Pompeii two thousand years earlier. I feel it’s the first time I’ve made such an express declaration of love to cinema; not with a specific sequence, but with a whole film. To cinema, to its materials, to the people who give all they’ve got around the spotlights, to the actors, editors, narrators, those who write, to the screens which show the images of intrigues and emotions. To films as they were made at the moment they were made. To something that, although you can make a living from it, is not only a profession but also an irrational passion.

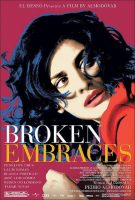

Broken Embraces (2009)

Los Abrazos Rotos

Directed by: Pedro Almodovar

Starring: Penelope Cruz, Lluís Homar, Blanca Portillo, Jose Luis Gomez, Ruben Ochandiano, Ángela Molina, Chus Lampreave, Kiti Mánver, Lola Dueñas, Mariola Fuentes, Carmen Machi, Kira Miró

Screenplay by: Esther Garcia, Agustin Almodovar

Production Design by: Antxón Gómez, Víctor Molero

Cinematography by: Rodrigo Prieto

Film Editing by: José Salcedo

Costume Design by: Sonia Grande

Set Decoration by: Marta Blasco, Pilar Revuelta

Art Direction by: Víctor Molero

Music by: Alberto Iglesias

MPAA Rating: R for sexual content, language and some drug material.

Distributed by: Sony Pictures Classics

Release Date: November 20, 2009

Views: 240