Cloverfield Movie Trailer. The result is an adrenaline-charged roller-coaster ride, with the audience’s connection to the characters maintained through the eye of a single camera. The technique lends itself to keeping us in touch both with the characters and with what’s going on around them, in what has become, in recent years, a most familiar style of image capture: the personal camcorder.

“When I first had the idea for the film, I began thinking about the impact of the YouTube-ification of things,” says Abrams. “Today, if you look online for two minutes, you can find video — whether it’s from Iraq, London, Spain or Manhattan — of people hiding in a store or hiding under a car, and watching other people’s reactions.”

Watching such footage — as seen in countless homemade catastrophe videos — has an unusual effect on the viewer. “In this YouTube era, watching this kind of video has a voyeuristic quality, even if you’re just watching people do mundane things,” notes Goddard. “For some reason, when it’s real, you can watch it forever — it’s like you’re intruding on people’s lives.” And we knew that, for the movie to work, it had to feel real — like you’re watching somebody’s party, peeping in on them — so that when the chaos starts, you would automatically transfer that reality to the monster.

The experience was similarly unique for the actors. “You feel like you’re a part of the movie, as opposed to being an outsider,” says Jessica Lucas, who plays Lily in the film. “You really feel like you’re going through this experience with these characters.”

The challenge for the filmmakers was how to recreate this kind of footage for narrative cinematic purposes. “We asked ourselves, `What does it look like when people are videotaping a spontaneous, horrific event?'” says Abrams. “It was an incredible readjustment,” says Reeves, “because, in trying to create the illusion of only one camera, you were working without the usual cinematic tools. So there’s no big wide shot, no reverse shot to show the other person watching and listening. Everything you see and know comes from Hud’s camera and his point of view.”

A limitation on the types of shots available proved to be a key element in the film’s look of authenticity. “It had to feel like something that was not made by experienced filmmakers,” Reeves continues, “but by people who just found themselves in the midst of this situation.”

Adds Burk, “We wanted the film to look like real life, as if a giant monster was attacking my city and I grabbed my camera and ran out into the street — and this would be exactly the footage I’d have.”

Doing so required the development — or, rather, replication — of a visual grammar that gave the impression of a novice using a video camera and trying to capture the frantic chaos around him. “It had to look amateurish,” says director of photography Michael Bonvillain. “It still had to sell the story points, but in this case, as captured by someone who isn’t a trained operator.”

An important quality of this technique — one which adds incredible terror and tension to many scenes — is having the camera operator “just miss” much of the action, including sightings of the monster. “So much of what’s conveyed in real amateur or documentary footage is what you hear but don’t see — the panic and reactions to what’s happening off-camera and the sounds of things you don’t see,” explains Abrams.

“There’s something very scary about what you can’t see,” adds Reeves. “You’re in there with Hud, and there’s no reverse angle showing you what he’s not seeing. They don’t have any more information than you do. Every moment becomes charged, because you know that, just off-frame, there might be something horrible happening. But you don’t know what it is, because he hasn’t turned the camera there yet. It becomes all about what your mind fills in.”

Portraying intriguing action has a curious effect on the audience, says Sherryl Clark. “Picking those moments, and showing just enough to get the audience frightened and excited, leaves them wanting more.”

In “Cloverfield,” the camera often provides only snippets of what has just passed by — i.e., the monster — accompanied by a comment from one of the characters such as “What was that?” or “Can you see it? What is it?”

“The idea is that it all appears to be haphazard, so that you might catch a glimpse of something out of the corner of your eye and you’re not quite sure what it is,” explains visual effects supervisor Michael Ellis. “Hud is very much led by the direction the other characters are giving him. They usually see something before he does, and he tries to find it; but by then, he’s already too late. He’s just missed it. His friends are already running away.”

One difficulty in creating these “amateurish” shots lay in the fact that there were seasoned professionals behind the camera like Chris Hayes. “Chris is amazing,” says Reeves. “But sometimes he’d operate almost too well. I’d say, `I need this to feel more accidental.’ Because, at the end of the day, we wanted it to feel like anybody with a camera could have made this movie.”

A key solution turned out to be a fairly obvious one: have actor T.J. Miller, who plays Hud, operate the camera himself, which he did for a number of sequences. “T.J. actually operated a lot,” explains Bonvillain. “He was always joking that he should have gotten his union card for all the work he did.”

Having Miller operate the camera had several advantages. “For one thing, he had good instincts of what to do, because he is Hud,” Bonvillain continues. “Also, having him operate helped us make sure we were providing the right eyeline for the other actors in the scene, so that it felt correct when people were talking to him.”

“I wasn’t just an actor,” Miller says. “In some ways, I was a cameraman, and in most ways, I was a voice-over artist.”

The experience was, as one would expect, a bit daunting at times, he admits. “It was hard. You know, I’m thinking about camera movement, and ‘Do I shoot over here?,’ and they’d come in and say ‘Okay, we need you to tilt up and then pan left after her line.’ And I’m thinking ‘Okay, cool. And how about the acting? Was that good?’ It was a lot to juggle.

If one of the professional camera operators was shooting a scene, Miller would often stand behind him with his hands on the operator’s shoulders, again, to provide an appropriately realistic eyeline for his fellow cast members. And, in the instances during which the operator had to physically interact with one of the actors as if he were Hud, he would don Miller’s costume.

Orchestrating entire scenes all shot on one camera – some with extremely long takes – took great skill and planning. In a more typical movie, a scene would be made up of cuts photographed from a variety of angles, shot over several takes, each of which would have provided specific information for the scene. In “Cloverfield,” the frenetic camera movement had to be carefully planned out to capture any activity Reeves wanted the audience to see.

“We had to take a lot of things that were really well-rehearsed and find a way to make them seem accidental,” the director explains. Adds Abrams, “Matt did a lot of things that are incredibly complicated — making shots look as if they were continuous and staging things in a way that felt spontaneous, which they hardly were.”

Many of the film’s shots were planned out ahead of time using “previsualization” animation provided by the Los Angeles-based Third Floor, says Michael Ellis. “It helped give the actors and the cameraman some clue as to where they were supposed to be pointing and what exactly it was they were trying to run away from.” If Miller was operating the camera, Reeves and Bonvillain would walk through the scene rehearsal with him. Sometimes they would shoot the rehearsals with a smaller video camera, then massage the scene until it was to their liking, before proceeding to shoot it for real.

Scenes in which the monster is spotted took careful strategizing — again, to limit sightings to “glimpses” during sequences earlier in the film, gradually leading to full-on views as the movie progressed. For the most part, the monster is seen only from ground level, since that’s where Hud is for the majority of the film. “And that creates a very unique perspective,” notes Reeves.

Eventually, though, says Goddard, “We realized that you do owe the audience a shot of the monster.” The aerial, “God’s eye” shots of the monster the audience would see in a traditional film are absent in “Cloverfield” — save for one or two carefully-planned sequences, such as a helicopter shot that Reeves worked into the film. “When they’re in an electronics store and people are watching news coverage on TV sets, you see a helicopter shot of the monster as his tail swings and takes a chunk out of the Brooklyn Bridge,” explains the director.

A more intimate view of the monster occurs when our cameraman, Hud, is attacked by the monster, revealing the inside of the creature’s mouth briefly to the camera before it is spit out and lands on the ground. Reeves notes, “Drew said to me, `To a monster movie fan, the idea of being eaten by a monster — there’s nothing cooler.'”

Building a Better Monster

The visual effects for “Cloverfield” were produced under the direction of visual effects supervisors Kevin Blank, Eric Leven of Tippett Studio and Michael Ellis of London-based Double Negative. Tippett created all the shots that include the monsters, while Double Negative was responsible for all of the other destruction and sequences which did not include the monster.

The concept for the monster (affectionately known simply as “Clover” in-house) is simple, says Abrams. “He’s a baby. He’s brand-new. He’s confused, disoriented and irritable. And he’s been down there in the water for thousands and thousands of years.”

And where is he from? “We don’t say — deliberately,” notes Goddard. “Our movie doesn’t have the scientist in the white lab coat who shows up and explains things like that. We don’t have that scene.”

Not only is the creature disoriented — he’s downright angry. “There are a bunch of smaller things — humans — that are annoying him and shooting at him like a swarm of bees,” observes Reeves. “None of these things are going to kill the monster, but they hurt it and it doesn’t understand. It’s this new environment that it finds frightening.”

For the monster’s design, Abrams engaged veteran creature designer Neville Page, who had just finished creating characters for James Cameron’s upcoming “Avatar” (and is currently working on Abrams’ “Star Trek”).

“So much has been done in so many different movies with large creatures that the trick was to find a way to create a unique character,” explains Abrams. The producer had first become familiar with Page’s work through the designer’s series of instructional DVDs for The Gnoman Workshop. “One of the things that struck me about Neville’s instructional videos was the way he approaches everything from a realistic point of view. He develops non-existing creatures, but can explain to you their physical makeup, musculature and skeletal structure.”

Adds producer Burk, “Neville was the first person we met with. And he’s amazing. He doesn’t just think about designing the creature, he thinks in terms of how it would walk, how it would breathe, what its skin would be like, how it lives — everything.”

Once Page’s designs were complete, it was up to Tippett Studio to implement and refine the monster for inclusion in the few — but crucial — shots in which he appears. “We did a test, where we inserted him into some background plate shot in downtown L.A.,” explains Leven. “We experimented with different looks, in terms of not only the creature itself, but how it would interact with the camera and with light.”

Another facet of the design was added at director Reeves’ suggestion. “I wanted him to have that sort of spooked feeling, the way, when a horse is spooked, you can see the white of its eyes along the bottom. And you see that when the military is firing on him, where he becomes completely agitated and confused.”

As part of a “post-birth ritual,” as Abrams describes it, the monster is seen early on scratching his back on a building (destroying it in the process), to remove a layer of parasites that are set loose to wreak their own havoc on the city.

“Drew and I were struggling with, `When you have a monster that size how do you keep the characters from seeming totally irrelevant?'” says Abrams. “How do you have any one-on-one struggle?” Explains Goddard, “Because he’s so big, we knew it was going to be difficult to have intimate sequences. It’s not like any of the characters could fight him or that anyone could even figure out a way to hurt him.”

And because of that, the idea of the parasites was born. “They’re these horrifying, dog-sized creatures that just scatter around the city and add to the nightmare of the evening,” Abrams says.

“The parasites have a voracious, rabid, bounding nature, but they also have a crab-like crawl,” Reeves explains. “They have the viciousness of a dog, but with the ability to climb walls and stick to things.”

In addition, the parasites also move more rapidly than their giant host counterpart. “Tippett Studio has a lot of expertise with these kinds of fast-moving creatures that can destroy people and rip them to shreds, which is always a lot of fun to work on,” says Leven. “They’re like little whirling dervishes that just destroy anything in their path. They’re totally deadly.”

Crushing The Big Apple

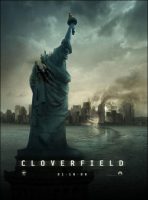

One of the first hints of the destruction brought on by the monster’s devastating tantrums comes early in the film, as the core group of young friends leaves Rob’s party to find out what the commotion outside is all about — only to be greeted by the head of the Statue of Liberty bouncing down the street.

The shot was originally featured in a two-minute teaser trailer filmed in late May 2007, which appeared just a few weeks later attached to Michael Bay’s summer blockbuster “TRANSFORMERS.” The trailer contained a variety of shots, including party scenes, Miss Liberty’s head and other depictions of destruction, all of which were shot prior to the start of production on the film.

“The Liberty head sequence was a huge leap of faith from the studio,” explains Burk. But the trailer had an immediate impact on genre fans. “The reaction was just what we’d hoped for,” notes Abrams. “No one had heard of this movie yet. We didn’t even put a title on it, something the MPAA had never seen before.”

The title of the film, though seemingly cryptic, actually came out of the producers’ desire to keep news of the production quiet until the time was right. “We wanted to make a movie that no one knew about and then let them discover it, the way we used to discover movies growing up,” says Abrams.

Interest in the film, based on just the trailer, has been, to say the least, remarkable. “I certainly didn’t expect the outpouring of curiosity and intense scrutiny of this project,” says executive producer Clark, “or people sneaking onto the set and taking photos and video. It’s been intense. People are very interested in J.J. and what he has to say.”

It was, in fact, one of Abrams’ and Burk’s agents, John Fogelman, who, having seen the word “monster” one too many times in private e-mail correspondence, suggested calling the project “Cloverfield,” after a main street near Abrams’ office in West Los Angeles. “We started working on the movie, and it became like a nickname. But we thought, `There’s no way that’s going to be the title of the movie,'”

Abrams recalls. “We even had another title, `Greyshot,’ the name of the bridge that Rob and Beth are hiding under in Central Park at the end of the film, which we were all set to announce at Comic-Con. But, by that time, the name `Cloverfield’ had already leaked out, and the fans already knew it by that name, so we just decided to stick with that.”

The shocking Liberty head shot was filmed on the Paramount back lot and created originally by Studio City-based Hammerhead Productions (the shot, later reused in the feature film, was advanced by Double Negative to include more detail). It’s Abrams’ homage to John Carpenter’s 1981 film “Escape From New York,” which featured a similar image in its original theatrical poster. “I loved that movie as a kid,” he says, “but one of the things that drove me crazy is the poster had this picture of the head of the Statue of Liberty sitting in the middle of a New York street — but it was never in the movie,” says Abrams. “And I always felt that was such a crazy, scary image, that it had to be in our movie.”

Difficult as it was to give a fictional 25-story monster a sense of authenticity (which for Reeves was crucial to the success of the film), Tippett Studio and Double Negative were further challenged to create scenes of destruction that had to look real to an audience for whom scenes of falling buildings in New York are all too well-etched in their minds.

A few years ago, few people had any idea of what a building looked like when it collapsed. “Now,” says Michael Ellis, “when a building collapses in a particular way and throws off a huge amount of dust, it’s recognizable to everybody.” “Again,” notes Leven, “YouTube has changed the game in terms of visual effects references.”

Double Negative already had experience with similar destruction shots. In this case, though, Ellis notes, “the building is collapsing as a result of being knocked down by an enormous monster, so it has to fall in a specific way.” The cloud dust that results from the buildings’ collapse was created specifically to meet Reeves and Abrams’ requirements. “We did research and development in recreating that kind of dust bowl coming down a street,” says Ellis. The dust cloud’s movement was simulated using fluid dynamics, recreating the specific way in which a huge amount of dust and debris behaves when it’s sent cascading along a canyon of buildings.”

For the actual collapse of the buildings, the two teams worked tirelessly to fulfill Reeves’ desire for realism. “We would model floors of the building on an exterior structure, and then just destroy the building layer by layer,” Leven explains. “We’d start with the glass outside, and then the floors inside. We even built bits of furniture. It’s super time consuming, but everyone involved in this project loves this kind of work — it’s every little boy’s dream to blow stuff up!”

Particularly tricky was creating “shaky” visual effects as seen through what is supposed to be a roughly-handled camcorder. While it is now commonplace for effects houses to employ a team of “match movers,” who track the jump of each frame to the next so the computer-generated characters will move to match, “Cloverfield’s” handheld footage multiplied that challenge exponentially.

“Normally our software can solve most tracking problems with a degree of automation,” says Ellis. “But many of these shots proved too complex. It was a humongous task; we had people tracking the shots by hand, frame-by-frame. Zooming shots are always hard to track, but these shots with their increased jerky handheld nature were very difficult. No gentle smooth movement — the camera was all over the place.”

Among the more familiar landmarks destroyed by the monster was the 125-year-old Brooklyn Bridge, which gets swiped by the monster’s tail. A 50-ft. section of the bridge was constructed at The Downey Stages in Downey, California, surrounded by a 360-degree green screen, which was later replaced by background plate shots taken at the real bridge. The horde of extras hired to portray the stampede of panicking New Yorkers trying to escape the creature through stopped traffic on the bridge actually parked their own cars on the “deck” level of the specially constructed structure to fill out the shot.

To reproduce the rest of the bridge, Ellis’s team photographed and measured the real Brooklyn Bridge, from which a full computer-generated bridge was then built. Ellis and his animators also studied footage of real suspension bridge collapses such as the infamous 1940 collapse of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington. “We studied it carefully to see how suspension bridges break up and tried to get as much excitement as possible into the shot,” he explains.

While the filmmakers wanted to create as much of that excitement and realism as possible for the audience’s enjoyment, they were also extremely conscientious about the implications of these sequences. “In a lot of ways,” says Reeves, “the monster is kind of a metaphor for our times and the kind of terror we all face. So it was important to find a way to approach those feelings without diminishing or exploiting them, and to do so in a way that wouldn’t be disrespectful.”

The film carefully avoids crossing the line from realistic scares to all-too-painful reminders of recent events — through a unique point-of-view experience, humor, and Reeves’ reconnection of the audience with the characters throughout the film. The visual effects teams even took care that the collapsing buildings in the film were older-looking structures that did not evoke the style of the structures that were attacked six years earlier.

Stirring up uncomfortable feelings is not entirely without purpose for a monster movie, Abrams notes. It’s a standard of the genre. “‘Godzilla’ came out in 1954 in the shadow of the bomb being dropped in Japan. Culturally, you had people living with this terror they had experienced — but in the guise of something absurd and preposterous. My guess is that it enabled people in Japan to have a catharsis.”

“To me, that’s one of the most potentially impactful aspects of this movie,” he continues. “It takes so many images that are so familiar, that are potentially horrifyingly scary, and puts them in a context that is ludicrous and laughable, so that people can experience catharsis in a way that doesn’t feel like they’re going through therapy. People have a hunger to experience that, and to process the terror we all live with in a way that doesn’t feel like you’re getting a social studies lesson. And at the end of the day, whether or not that’s something they’re aware of, this movie allows them to have that release. And for younger kids,” he says, “you just have one heck of a great monster movie.”

Fear Itself: Monsters At the Movies

“In the same way that ‘Godzilla’ was about the anxiety of the nuclear age, and the atomic bomb and Hiroshima, the monster in `Cloverfield’ is a metaphor for our times and being able to find a way to approach those feelings without diminishing or exploiting them.” — Matt Reeves, Director, “Cloverfield”

Dracula. Godzilla. Freddy Krueger. Foreboding, violent monsters (in human, animal or alien form) who wreak havoc on an innocent public, have been drawing audiences to theaters since the silent era, offering catharsis from personal anxiety and serving as metaphors for the general fears plaguing the culture during a particular era.

Some of the earliest movie monsters hail from the German expressionist film movement that began during World War I and continued through the 1920s. The central fiends in such films as Paul Wegener’s “The Golem,” Robert Wiene’s “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” and F.W. Murnau’s “Nosferatu” were controversial depictions of the malaise in war-devastated Germany. Those films were a direct influence on iconic American movie monsters of the `20s and `30s, including “Frankenstein,” “Dracula,” “The Phantom of the Opera” and “The Invisible Man” — exotic foreign demons during an era of pronounced xenophobia and isolationism in the U.S. Not coincidentally, the film’s villains often preyed upon scantily clad females at a time when the country’s inbred Puritanism was being challenged by the “Roaring `20s,” a period of change for women, who not only won the right to vote, but also to bob their hair, raise their hemlines and dance the Charleston.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the monsters became even more menacing, expressing the paranoia and sense of impending doom that characterized the Cold War period. Despite Franklin Roosevelt’s soothing Depression-era promise, there seemed to be something more to fear than fear itself. Movies like “The Thing” and “The War of the Worlds” were populated by mutant beings or evil extraterrestrials bent on destroying the American way of life. The alien invaders in “The Day the Earth Stood Still” could be seen to represent the threat of ideological takeover by communist Russia, while “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” was a thinly-veiled critique of Joseph McCarthy’s “communist under every bed” hysteria. Ironically, the country’s greatest weapons were of little use against creatures like “Godzilla,” a horrifying by-product of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, while the giant ants in “Them!” raised serious questions about the safety of using nuclear power.

The gloomy foreboding of the `50s monster movies was mitigated by the public’s faith in the power of the central government to pull together to tackle these threats. They had, after all, proved victorious in World War II, which was followed by one of the biggest economic booms in our history. Concurrently, as in the 1920s, the country’s conservative, puritanical streak resurfaced in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” and “The Birds,” which spotlighted two very different kinds of monsters, who exacted revenge on women who too freely expressed their desire for independence.

But by the 1960s and 1970s, that safety net was frayed and the public’s blind belief in their leaders’ ability to save them in a time of crisis came under serious scrutiny. In these films, if disaster struck, it was every man for himself. The monsters in “Jaws” and “Alien” were all the more frightening because they prospered through greed with little regard for public safety. What was good for General Motors…

As the Vietnam War shook the country’s faith in their government, it also influenced writers, philosophers and theologians to question the metaphysical implications of these events. A significant trend in horror movies dealt indirectly with the war (George A. Romero’s landmark 1968 zombie thriller “Night of the Living Dead” — which also included references to the civil rights movement), while Tobe Hooper’s 1974 classic “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre played on fears about the dissolution of the traditional American family. In these movies, we saw the enemy — and it was us.

The idea of God turning away from society surfaced during movies of the era, introducing the scariest monster of them all — Satan. Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby,” William Friedkin’s “The Exorcist” and Richard Donner’s “The Omen” made this villain of all villains more tangible (and horrifying) by having him inhabit the body of a child.

If the devil himself could appear in the most unlikely of places, then clearly no one was safe — not even suburbanites. By the 1980s, the exodus away from the dangers of city life (drugs, racial tension, sexual license) to the controlled family-friendly environment of planned communities proved to be no panacea for the happy family in “Poltergeist,” who had unwittingly upset the natural order (again due to greedy, unscrupulous land developers) by moving into a house built on a sacred Native American burial ground. Again, revenge was taken out on the most vulnerable among us — the children.

The sexually maladjusted Norman Bates in Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” evolved into an army of crazed and tormented monsters like Jason in the “Friday the 13th” series, Michael Meyers in “Halloween” and “Nightmare on Elm Street’s” Freddie Krueger. The message to the teens who populated (and watched) these movies couldn’t have been clearer: You have sex, you die. Things went from bad to worse in films like “The Hunger” and David Cronenberg’s remake of “The Fly,” which evoked the AIDS epidemic and the explosion of other sexually transmitted diseases.

With the end of the Cold War, the monsters of the 1990s turned out to be the seemingly normal next-door neighbor who turned out to be a pedophile, a crazed fan or a cannibalistic mass murderer: Dr. Hannibal Lecter of “The Silence of the Lambs,”; Annie Wilkes in “Misery”; and John Doe in “Se7en.”

But, just as the new millennium began, incomprehensible real-life horror overshadowed anything that was being shown in theaters. Not only was the country’s always-fragile sense of vulnerability truly challenged for the first time since Pearl Harbor, but it seemed like a prelude to the end of days. Everywhere one turned there was another potential devastation — Ebola, SARS, bird flu, anthrax and global warming. And movies responded with films like “28 Days Later,” a contemporary remake of “Body Snatchers” called “The Invasion” and, most recently, “I Am Legend.” Xenophobia resurfaced in a more diabolical manner in films like “Hostel,” “Saw” and “Touristas” — torture fests that eerily coincided with a heated debate over the use of torture in wartime. And in another remake, “Poseidon,” the monster was a tsunami-like wave, not unlike the one that had overwhelmed Southeast Asia only months before.

In Steven Spielberg’s frightening remake of “War of the Worlds” aliens, without provocation, lay waste to the earth — and we are unable to stop them. It’s the earth’s atmosphere — replete with bacteria and viruses — that finally destroys them. Mother Nature came to our rescue, but there wasn’t much to be happy about, since she also gave us the cold shoulder in “The Day After Tomorrow.” Most of North America is covered with a blanket of ice and, as in “War of the Worlds,” it has happened without so much as a warning (or maybe we weren’t listening), making the U.S. largely uninhabitable.

The nature of new, previously unforeseen threats to our way of life, has led to a new breed of monster movie that reflects not only the uncertainty of our era, but our sense of powerlessness in the face of such daunting obstacles.

Cloverfield (2008)

Directed by: Matt Reeves

Starring: Michael Stahl-David, Mike Vogel, Odette Yustman, Lizzy Caplan, Jessica Lucas, Margot Farley, T. J. Miller, Liza Lapira, Lili Mirojnick, Elena Caruso, Maylen Calienes

Screenplay by: Drew Goddard

Production Design by: Martin Whist

Cinematography by: Michael Bonvillain

Film Editing by: Kevin Stitt

Costume Design by: Ellen Mirojnick

Set Decoration by: Robert Greenfield

Art Direction by: Doug J. Meerdink

Visial Effects by: Double Negative, Tippet Studios

Music by: Johnny Greenwood

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for violence, terror and disturbing images.

Studio: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: January 18, 2008

Views: 106