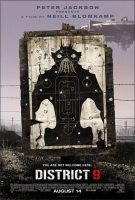

Tagline: You are not welcome here.

District 9 movie storyline. Over twenty years ago, aliens made first contact with Earth. Humans waited for the hostile attack, or the giant advances in technology. Neither came. Instead, the aliens were refugees from their home world. The creatures were set up in a makeshift home in South Africa’s District 9 as the world’s nations argued over what to do with them.

Now, patience over the alien situation has run out. Control over the aliens has been contracted out to Multi-National United (MNU), a private company uninterested in the aliens’ welfare. MNU will receive tremendous profits if they can make the aliens’ powerful weaponry work. So far, they have failed; activation of the weaponry requires alien DNA.

The tension between the aliens and the humans comes to a head when MNU begins evicting the non-humans from District 9, with MNU field agents responsible for moving them to a new camp. One of the MNU field operatives, Wikus van der Merwe (Sharlto Copley), contracts an alien virus that begins changing his DNA. Wikus quickly becomes the most hunted man in the world, as well as the most valuable – he is the key to unlocking the secrets of alien technology. Ostracized and friendless, there is only one place left for him to hide: District 9.

District 9 is a 2009 science fiction action horror film directed by Neill Blomkamp, written by Blomkamp and Terri Tatchell, and produced by Peter Jackson and Carolynne Cunningham. It is a co-production of New Zealand, the United States, and South Africa. The film stars Sharlto Copley, Jason Cope, and David James, and was adapted from Blomkamp’s 2006 short film Alive in Joburg.

As of 4 November 2009, District 9 had grossed an estimated US$210,819,611, of which US$115,646,235 was from Canada and the United States. Its production budget was US$30 million. It opened in 3,048 theaters in Canada and the United States on 14 August 2009, and the film ranked first at the weekend box office with an opening gross of US$37,354,308. Among comparable science fiction films in the past, its opening attendance was slightly less than the 2008 film Cloverfield and the 1997 film Starship Troopers.

The audience demographic for District 9 was 64 percent male and 57 percent people 25 years or older. The film stood out as a summer film that generated strong business despite little-known casting. Its opening success was attributed to the studio’s unusual marketing campaign. In the film’s second weekend, it dropped 49% in revenue while competing against the opening film Inglourious Basterds for the male audience, as Sony Pictures attributed the “good hold” to District 9’s strong playability. The film enjoyed similar success in the UK with an opening gross of £2,288,378 showing at 447 cinemas. It was just as popular in South Africa,[citation needed] where it was filmed on location.

About the Production

“Neill Blomkamp is a terrifically exciting young director,” says producer Peter Jackson, who shepherds Blomkamp’s debut feature film, District 9. “We were considering a production of Halo, based on the video game. That movie never happened, but we loved working with Neill so much that when he pitched us District 9, we decided it would be fun to turn his idea into a feature film.”

In District 9, Blomkamp deftly creates a film with an original vision and unique method of telling its story. After cutting his teeth as a visual effects artist and director of music videos and commercials, Blomkamp makes his feature film directorial debut, drawing inspiration from classic science fiction films as well as the Johannesburg of his youth (Blomkamp was born and raised there before relocating to Canada). The result is a film that breaks ground with a new, thrilling voice. From the very beginning, Blomkamp intended District 9 to be unconventional and to blur the lines between filmmaking styles.

“Essentially, the film bounces from our story, which is obviously fictional, to a sort of ultra-real mode,” explains Blomkamp. Dramatic scenes, mockumentary footage, real news video obtained from the South African Broadcasting Corporation – “it’s all part of the same story,” Blomkamp continues. “The movie fluctuates between something that feels like a film and something that feels bizarrely real.”

“District 9 is set in an alternate history,” says Jackson. “Imagine over 20 years ago, over a million alien refugees arrived on earth in a derelict spaceship. They are benign – more than that, they are helpless. They can’t even feed themselves and have no particular desire to do anything. They come to Johannesburg, of all places, and the government doesn’t know what to do with them, so the aliens end up in a township very similar to Soweto. And for over 20 years, humans have been trying to solve the alien problem.” Blomkamp says the film mimics the 24-hour news feed that cable channels, the internet, and other news sources feed us every day.

“It used to be that you would pick up a single newspaper story. Now, the imagery is always there and we have become used to it,” says Blomkamp. He also points out that the advent of reality television blurs the lines between reality and entertainment even further.

The genesis of District 9 lies in a short, low-budget mockumentary called Alive in Jo’burg that Blomkamp shot in a Johannesburg shantytown a few years ago. In the short film, Blomkamp introduces intergalactic aliens to the cultural mix of Johannesburg, one of Africa’s most dynamic cities. For that film, Blomkamp hit the streets with a camera crew, looking to capture reactions from real people.

Blomkamp soon discovered that his idea of intergalactic refugees suddenly arriving on the city’s doorstep dovetailed with the real conflict and xenophobia prevalent amongst the citizens of Johannesburg towards the influx of illegal aliens from neighboring countries. The honest reactions he captured on camera brought a vitality to the short film, blurring the line between fiction and reality.

Of the short, Blomkamp says, “I was not intentionally trying to deceive the people we interviewed. I was just trying to get the most completely real and genuine answers. In essence, there is no difference except that in my film we had a group of intergalactic aliens as opposed to illegal aliens.”

Because District 9 is set in South Africa, some may suggest that the film is a direct metaphor for the many problems that country has faced over the years. The filmmakers say that though it’s impossible to divorce the film from its setting, no direct metaphor is intended.

“In South Africa, we have to deal with issues that generally people around the world try to sweep under the rug,” says Sharlto Copley, who plays the lead character, Wikus.

Working with the thematic and visual ingredients of the short film as a springboard, Blomkamp and his writing partner Terri Tatchell fleshed out the character of Wikus, and introduced two central alien characters, Christopher Johnson and his son, Little C.J. (The writers gave the aliens human names, imagining the re-naming humans would do when admitting the aliens to our planet). It was important to the writers that all of the characters, even and especially the aliens, were believable, recognizable – well, human.

Drawing on people they knew or were familiar with, the writers created a cast of characters who are an amalgamation of many people.

Blomkamp’s childhood friend and collaborator, Sharlto Copley, takes on the role of Wikus van der Merwe, the MNU official charged with removing the non-humans from District 9 and moving them to the concentration camp of District 10. Copley had also worked on the short film Alive in Jo’Burg, producing that film.

“Neill has found a very soulful way of approaching science fiction,” says Copley, who has known Blomkamp for over 12 years. “The genre can be clinical, even cold and unemotional. But in Neill’s hands, it resonates quite deeply. There’s no particular message or big moral of the story – it’s just a melting pot of emotions that comes out.” Copley says that he was thrilled to continue working with Blomkamp.

“There is a very small film industry in South Africa,” he says. “So even if you meet someone else who wants to work in film, it’s not necessarily a person that you can resonate with or gets your creative point of view. So I feel very fortunate that Neill’s one of those people that I always got what he was trying to accomplish, and he saw things in me, too.”

“A small amount of power goes a long way with Wikus – he’s an ordinary guy who likes to wield power in a bureaucratic way,” says Copley. “That’s why MNU promotes him – they want a guy who will do things in an orderly, proper way.” “Wikus has a very bad day,” says Peter Jackson. “Not only does he contract a mysterious disease that starts changing his DNA, but what makes it worse is that he becomes the key to unlocking the alien weaponry. For a moment in time, Wikus becomes the most important person on the planet.”

David James plays Koobus, MNU’s chief enforcer, who becomes a bounty hunter of sorts when MNU’s chiefs order Wikus to be brought in – dead or alive. “Koobus is the dark side of MNU,” says James. “If you need something done legally, you get Wikus, and if you need it done even if it’s not legal, you get Koobus. Everyone at MNU know that Koobus is not somebody you mess with.”

“I think Neill liked the psychopathic edge I gave to Koobus in my audition,” says James. “He can lie so convincingly to everyone around him – he’s operating with his own agenda. Whenever I was in doubt about what my character would do in a situation, I went back to that.”

Another subtle clue to character might go over the heads of most Americans, but plays into a kind of bigotry that South Africans would know. “Wikus is Afrikaaner, which is perceived by some in South Africa as a kind of a redneck,” says James. “I decided that I would play Koobus as English, a man who has spent his military service out of country.

Even at the outset, in every way, he sees himself as being superior to Wikus.” Jason Cope, who had served as Blomkamp’s production manager on Alive in Jo’burg, plays the non-human Christopher Johnson. “Actually, I play about ten different characters,” says Cope. “It was quite a thing to wake up and say, `Which creature will I be today?’ My mom was very excited when I got the part. She asked, `What are you doing?’ I said, `I’m playing a community of intergalactic beings in the townships.’ She couldn’t quite get her head around it.”

“Neill had a very clear idea about what he wanted from the non-humans,” Cope continues. “During the rehearsal process, we got a feel for what he liked, but he also gave me a lot of freedom, within certain boundaries. I wouldn’t act too much like an animal or an insect, but I’m definitely not acting human, either.” “Jason is a terrific actor to play off of,” says Copley. “Those were some of the best scenes in the film, for me.”

About the Cinematography

From the very beginning, Blomkamp intended that District 9 would stand on its own – influenced by the great science fiction films that came before it, but unique in vision and groundbreaking in method.

District 9 breaks the rules most effectively in its style of shooting, which, by the end of the film, has audiences wondering what’s real and what’s entirely imagined. Blomkamp’s longtime friend, cinematographer Trent Opaloch, shared the director’s instinctive understanding of the trip he intended for moviegoers.

“Trent is perfect in this ultra-real, run-and-gun type of situation,” says Blomkamp. “We didn’t spend too much time painting a beautiful picture – we just got in there and captured a raw, authentic feel.”

Blomkamp uses three different components to tell his story. First, of course, are the dramatic scenes encompassing Wikus’s story.

With handheld cameras and other techniques, Blomkamp and Opaloch sought raw, brutal, and authentic-looking images. For example, Opaloch mounted dozens of mini-cameras on every set, which captured both the action as well as the filming process. The filmmakers also shot a “corporate video” for MNU, with Copley as Wikus speaking directly to the camera.

“That was the very first test we did,” says Copley. “It adds an extra layer to the film, showing how the character is `on-camera’ vs. `off’ – he’s trying to make himself seem impressive, show off a bit. When you get a little bit of the character when he thinks no one’s watching, it’s disarming – it fits right into the style of the film that Neill created – in the audience, you just believe it.”

The second component is the mockumentary footage. The filmmakers worked independently from the main unit, interviewing dozens of people, some actors and some not, to get the desired, off-the-cuff responses to the situation presented in the film.

The third component is real, existing footage sourced from the South African Broadcasting Corporation, Reuters, and other news agencies. This is mostly archival news footage used to help flesh out the world that Blomkamp has created.

“A lot of films will reference footage that they claim is existing footage, where you see a famous news presenter or a snippet from CNN, so what I am doing is not uncommon,” explains Blomkamp. “The only difference is that there is a greater amount of it in this film.”

Filming on Location

“Because Neill Blomkamp is South African, he brings a unique perspective to this story,” says Peter Jackson. The filmmakers always intended to shoot District 9 in Johannesburg, South Africa.

While the story could as easily have been set in any metropolitan city in any developing country, only Johannesburg has the unique African flavor that Blomkamp is both familiar with and inspired by.

“I think it would be incredibly difficult to replicate what we have in Johannesburg anywhere else,” says Blomkamp.

“There is so much visual detail here, the dirt or barbed wire or weeds, it’s incredibly rich visually. For the film to work, I think you need this level of reality and this level of pollution and realness.”

Actually, according to Sharlto Copley, the director did have a short moment when he wondered if it were really necessary to shoot in the townships. Copley, who would be in many scenes there and had produced the short, didn’t blink.“

Yes, I said. Definitely. I knew it would be grueling, but we had to do it. We couldn’t just build it on a soundstage. When you’re out there, all of the emotions come to the fore.”

The rise in crime levels has changed the city enormously in the years since Blomkamp decamped for Vancouver, but he has found these changes interesting and has incorporated them into his story.

“It has become a place of walled communities, barbed wire, electric fences, closed circuit television cameras, and private security firms,” says Blomkamp. “The changes could have made Johannesburg the ugliest city, but I find it visually stimulating and I absolutely love it.” For District 9, Blomkamp envisioned a harsh, somewhat apocalyptic vision of the city.

While keeping the authentic South African elements, he has also turned up the dial to create a fictional Johannesburg as a bleak and relentlessly grey place. To achieve that, the filmmakers shot the film in the dry winter months. In summer, the area is lush, green, and beautiful, but in District 9, not so much.

“We filmed in winter because I wanted the city in the film to look like a scorched earth, urban wasteland,” comments Blomkamp. “Filming in the dead of winter, and wherever you looked, there were fires and ash and pollution dotting the horizon, just what I wanted.”

The filmmakers were fortunate to find the perfect location in Tshiawelo, on the outskirts of Soweto.

People here had lived in shacks on a landfill for years; as filming was about to commence, the local authorities were moving them to state subsidized housing some 20km away and tearing down the shacks. The production bought up the shacks that remained, fenced off the area, and created a controlled environment in which to shoot.

“We completely lucked out with Tshiawelo,” says Blomkamp. “The location had the exact look that I had in my head.”

For production designer Philip Ivey, Tshiawelo and the shacks provided a solid base from which to work. “We had everything, including the garbage and scrap iron at our fingertips,” says Ivey.

“What we did was to buy up all the materials from the demolished shacks and then rebuild the shacks from those materials. This saved us having to distress the materials, gave a far more authentic look, and saved us a lot of time.”

Ivey had also brought on board as art director Emelia Weavind, who had worked in the same area a few years before as production designer on the Oscar winning film Tsotsi. “She is amazing and respects and loves people and, and they give it back to her in bucket loads.”

“As a South African, when you go out to the townships, there’s a lot of emotion,” says Sharlto Copley. “You never forget that this is a set for you, but there are real people living in those shacks. When you work in Soweto, the people who live there are glad to see you, because you bring a bit of an economy in there while you’re shooting.”

Ivey’s design for the film is essentially a contrast between the real-world, but also mundane, municipal world of the humans, and the larger-than-life, over-designed science fiction world of the non-humans.

“These two elements constantly clash in the film and that is what this film is all about,” says Blomkamp. “Everything that we built came from that same thinking.”

Somewhere between the ordinary world of the humans and the bizarre world of the non-humans lies Obesandjo’s lair. The character is a Nigerian underworld kingpin who is the non-humans’ only link to contraband, but not benevolent in any way. His home has its own unique style representing a multitude of different African influences. Here Ivey and Weavind created a multi-layered set that is both charming and foreboding.

“This space has many uses,” explains Weavind. “It is a pick-up bar, a chop shop and motor vehicle parts dealer, arms dealership and also traditional medicine (muti) store where a sangoma conducts rituals. We have designed and dressed it in such a way that wherever you look there is something interesting to catch the eye, from animal bones to jars of dead creatures to ammunition cases.”

Away from the harsh and dusty environment of Soweto, Ivey built a number of studio sets. One of Ivey’s favorites was the MNU Laboratory, a secret medical laboratory deep within the heart of MNU headquarters. When a hospital location fell through, the filmmakers decided to build the laboratory from scratch.

“We opted for heavy architecture with a basement feel,” says Ivey. “We wanted it to feel claustrophobic, as though it were closing in around Wikus. It definitely needed to be a threatening environment. We gave it fluorescent lights throughout to give it a cold sterile feel, and we painted the walls green, which is not very complimentary to anyone’s complexion.”

WETA’s On-Set Effects Supervisor Joe Dunckley notes that since the non-humans arrived on earth over 20 years before the film begins, that implies that any alien technology must have been around at least that long.

“One of the challenges was aging everything to give it a convincing feel,” says Dunckley. “We used a combination of shellac mist and water, which causes a reaction and it blooms and gives a nice crusty, rusty, aging.”

One of the most appealing aspects of District 9 for Blomkamp was the chance to bring his own vision of extraterrestrial life to the screen. “In designing the aliens, Neill didn’t go for the easy out,” says Terri Tatchell, the director’s writing partner. “They are not appealing, they are not cute, and they don’t tug at our heartstrings.

He went for a scary, hard, warrior-looking alien, which is much more of a challenge.” “I’m not sure exactly why I came up with this particular image, but it was very much an insect-like alien that I wanted for this environment,” explains Blomkamp. The development of these creatures was an organic process with input from Blomkamp as well as the designers at WETA Workshop.

“The basic idea was that they have an insect exo-skeleton crossed with that of a crustacean,” says On-Set Effects Supervisor Joe Dunckley. “They have sinewy, delicate joints between the hard shell areas, similar to a crab or crawfish. They’re meant to be entirely disgusting. They secrete some sort resin, so we used various forms of goo to give them that high shine and life-like appearance.”

The aliens are largely a marriage between visual effects and practical effects as their physical design – thin waists and dogleg lower limbs – would be difficult to animate otherwise. “Little C.J. will be entirely visual effects in the film, but we built a realistic dummy made out of silicone for visual effects reference,” explains Dunckley.

Blomkamp elected to use a mixture of visual effects and prosthetics in creating the aliens simply because while the prostheses provide a good point of reference while shooting, many of the design elements as well as movement is better achieved with visual effects. “These creatures have extremely thin waists and they are very difficult to create practically.”

The most advanced form of armor in the alien arsenal is the exo-suit, a combination of technology and organics that is in effect a living suit that attaches itself to the aliens that they control from within.

“The suit recognizes Wikus as an alien and mines into his brain,” says Blomkamp. “So even though the outside is metallic, it is sending him some kind of pain feed when the bullets are ricocheting off of him. The pain goes straight to his cerebrum.” For Stunt Coordinator Grant Hulley, the exo-suit represented a change in his approach to the stunts.

For most of the film, Hulley and his team tried to keep the mayhem moderate – “for example, someone was hit by machine gun fire, we would not have him flying through a wall,” says Hulley.

“When the exo-suit attacks, all hell breaks loose. We built a pipe ramp where the exo-suit would be, because the suit would be created by the VFX team in post. We did a 300 meter (1/5 mile) run up and hit the ramp at about 80km/h (50 mph), which sent the vehicle into a 270-degree flip into the air. To be honest, I’d never flipped a vehicle this big before so I wasn’t exactly sure how it was going to go.” He was pleased to note that the stunt exceeded expectations.

District 9 (2009)

Directed by: Neill Blomkamp

Starring: Sharlto Copley, Jason Cope, Nathalie Boltt, Sylvaine Strike, Elizabeth Mkandawie, John Summer, William Allen Young, Nick Blake, Louis Minnaar, Morena Busa Sesatsa

Screenplay by: Neill Blomkamp, Terri Tatchell

Production Design by: Philip Ivey

Cinematography by: Trent Opaloch

Film Editing by: Julian Clarke

Costume Design by: Dianna Cilliers

Set Decoration by: Guy Potgieter

Art Direction by: Emilia Roux

Music by: Clinton Shorter

MPAA Rating: R for bloody violence and pervasive language.

Distributed by: TriStar Pictures

Release Date: August 14, 2009

Views: 86