Family as a Universal Theme

Everybody’s Fine Movie Trailer. As a father of three, Jones connected only too well with the story of a father who wants nothing more than to do his best for his children but he also knows that parenthood can be very emotionally complex.

Says Jones, “Any father can relate to the conflicting instincts that are experienced by Frank in this story; realizing he has spent too little time with his children and family because it was necessary for him to work long hours to provide security for them. It is interesting to note that with all of the technological developments, balancing work and family remains one of the most challenging dilemmas facing modern parents. Frank worked double shifts at the wire factory, leaving for work before his kids got up and returning after they went to bed. Nothing has changed, addition of computers and email and texts and cell phones has promoted dea that we are always contactable, always working, covering different time zones, never completely relaxed or focused on the importance of home and family.”

Jones was also moved by Frank’s awakening to the reality that maybe his children didn’t turn out so perfectly. “Children aren’t meant to be perfect, families aren’t meant to be perfect. It’s about learning and growing and becoming more tolerant and it’s as important a journey for the parents as it is for the children, but expectations of children are too extreme in a modern world.

Parents are pushing their children to read and write and play musical instruments at an early age, the increase in exams at school for young children, of deadlines and targets leaves no time in the day allocated for children to rest or listen to stories or take a nap. I discussed the state of the American Dream in the modern world with people on my journey, the idea that you can achieve whatever you want to achieve if you work hard, I questioned whether children have unrealistic expectations of what they might achieve.”

Meeting De Niro…

Robert De Niro was Jones’ only choice for the role of Frank Goode. Jones traveled to New York with his producer Glynis Murray to pitch it to him for the first time in 2007.

Recalls Jones, “I was a little nervous because I was meeting arguably one of the greatest actors to have lived but more importantly I was very aware that I would only get one shot at the pitch. Within minutes I was completely relaxed in Bob’s presence. I looked at him and knew without a doubt that he was Frank Goode, I just hoped that he realized it too.”

“Bob was particularly interested in the idea of using real people and improvising scenes with non-actors. Above all he is a Dad, he got the project on all levels, he could immediately tap into the emotional tone and the universal theme of fatherhood,” Jones says.

Jones trusted producer Glynis Murray, who also made “Waking Ned Devine” and “Nanny McPhee,” to make the film with him and she was thrilled with the way in which the script developed. “Kirk used this opportunity to take the feeling of Tornatore’s movie and reset it in the much vaster landscape of America,” she says. “But I think he also brings out the completely universal topic of parents and children, which hits home whether you are British, American, Italian, Indian or whatever. A powerful theme of the film is misguided love. Frank is misguided in his expectations of his children and they’re misguided in keeping things from him, yet you can see there is real love there. It’s powerful stuff and I think an awful lot of people will see their own families reflected.”

The emotion and power of the script first came to light at a read-through with De Niro and actor friends in New York. Jones recalls, “It was a very special occasion the likes of which I will probably never experience again. I can’t really say too much about it because it was a private read-through and should remain private but those who were there recall it as being an extraordinarily emotional experience.”

Meeting Jones

“I liked Kirk a lot,” De Niro recalls. “When he showed me this whole presentation of photographs, I could tell there was something special about him and that this would be a special project from the standpoint of working with him, no matter how it turned out. Then I watched `Waking Ned Devine’ and that was it. From there, we simply figured out when we could start.”

De Niro also watched the original Tornatore version of the movie but he quickly saw that what Jones was going for was so different that it would have little application to his own performance. “I liked it, but it’s a whole different style of movie. It’s more heightened and stylized, and Mastroianni is doing a whole different thing, so I see them as two different beings, if you will,” he explains.

More influential on De Niro’s work in the film was his own deeply personal experience as a father. “I can identify with this stuff, to say the least,” De Niro remarks. “I can understand what Frank is going through with his kids and that’s what was so interesting to me.”

The tiniest details in De Niro’s performance brought out Frank’s underlying need and hunger for his children’s affection. Notes Glynis Murray: “When you watch De Niro in the supermarket walking along with his bag or taking his photographs and then carefully putting his camera back into the right place in his little bag, a lot of people instantly feel, `that’s my dad!’ He has that massive relatability.”

Also intriguing to De Niro was Jones’ approach. “It’s a very real story but there’s a certain kind of surreal, expressionist quality to what Kirk wanted to do with Frank stylistically and all the things he has in his head,” he notes.

While Frank’s offspring may all be modern professionals, Frank himself hails from blue collar roots, having worked for years in a telecommunications factory, coating the strings of telephone wire that crisscross the country carrying conversations – which makes it all the more poignant and ironic when his phone barely rings anymore. De Niro sees this basic foundation of Frank – his pride in the work of being the traditional breadwinner and his hope that this role is seen as a form of love – as the very core of his character.

“Frank sees all the wire he has coated as being the thing that made his kids what they are today,” says De Niro, adding: “For Frank, it’s everything; it’s the measure of his life.”

Jones recalls the casting and interview process: “I have never had anyone cry in a professional interview situation before but I would estimate that every fourth technician or actor who I met would start talking about their own family, their parents, their children and the script and then start to well up with tears. It was so consistent that it became quite comical and I found myself joining Glynis my producer in comforting people and reassuring them that this was very common. Although rarely explored I began to realize just how powerful the theme of family is to people. I was asked early on who I thought would go see the film and I said that I didn’t think anyone would want to see it…unless they have parents or brothers or sisters or children.”

Drew Barrymore, who plays Frank’s daughter Rosie, sums it up: “Clearly everybody’s not all that fine in the Goode family but that’s what modern families do, they put on a front – and that’s the heart of this story. The Goodes finally realize that it’s not supposed to be `everybody’s fine,’ it’s supposed to be `everybody’s experiencing what they’re really experiencing.’ Family is about loving each other even when things are tough, when heartache is happening, as well as when there’s great happiness and celebration. The greatest moments of family redemption are when there’s honesty in the air.”

Casting the Family

With De Niro on board Jones had to start to piece together the rest of the family. “Casting families can be a real challenge, there are basic physical requirements as well as the need to respect the chemistry between siblings. I wasn’t trying to cast a perfect family, I was casting a real family so I wanted the eldest sister to be bossy, for the youngest one to be vulnerable, etc,”

For the part of Rosie, the dancer seemingly living the high life in Las Vegas, Jones turned to Barrymore, who is not only one of today’s leading screen ladies but a filmmaker in her own right, having produced the “Charlie’s Angels” series and made her directorial debut this year with the roller derby comic drama, “Whip It.” “I could watch Drew forever on screen,” says Jones. “She has an extraordinary beauty and a very relaxed nature on camera. I think audiences feel very comfortable and connect with her because they have watched her grow up on screen.”

In turn, Barrymore was drawn by one thing: Kirk Jones. “I was really, really moved by Kirk’s writing,” she comments. “His style is very visual but also very emotional. And he gets to something that I think is a major epidemic in the world – families sweeping things under the rug. It’s a film about connecting and communicating and I found the whole concept intriguing. As you grow up, there is this shock at how distant people can become, how much they grow apart, and how hard it is to carve out time for family and friends. I liked that Kirk wanted to talk about that because I think it’s so important.”

She also had great affection for the song-and-dance Rosie tries to pull of for her father’s sake. “Rosie is putting on an act for her father because she know he’s really prideful that his little girl has realized all her dreams, so even though she’s struggling, she is not going to show him that,” Barrymore explains. “She’s trying to do the right thing, but, like her sister and brothers, she’s stuck in a cycle that needs to be broken.”

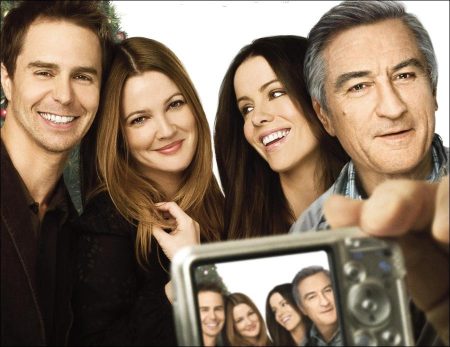

Barrymore says the character really came to life when she began working with her fellow cast mates. “I hate those fake Hollywood families where people do one read-through and suddenly they’re a family,” she says. “This was different because we spent time a lot of time together so that the tactile feeling of affection would come across between us.”

She continues: “I especially loved being sisters with Kate Beckinsale. She’s a very cool girl and a wonderful actress and that was an easy dynamic to jump into. And I’ve already done a number of films with Sam Rockwell, and it’s always a great pleasure having the chance to work with him again. With Robert De Niro, I felt I couldn’t just call him `Bob,’ so I started calling him `Daddy D.’ I wanted to get to know him well enough emotions would happen on screen.”

Kate Beckinsale, the English actress known for such films as “Pearl Harbor,” “Van Helsing” and “Snow Angel,” had a similar experience in preparing to play Amy, the advertising executive who is hiding some key facts about her married life from her father. “I think we all felt very connected and cobbled together, like a real family,” she says. “Everyone was full of emotions about the story. We might not have had the same experiences as our characters but the themes of secrets in families, of trying to protect your parents and the relationships between siblings was something everybody could relate to. It was especially personal to Bob and that sort of filtered down to each of us.”

Beckinsale notes that when Frank shows up at Amy’s architecturally spectacular modern house, he finds that the magazine cover surroundings don’t match what’s going on inside. “He shows up by surprise in this odd crisis moment and Amy just starts lying and it begins to spiral until she can’t stop,” she says. “I think for Amy it’s especially hard to let go of being the one person in the family who’s very successful in the practical parts of life. Her brothers and sisters are all artists, but she’s always been the responsible, pragmatic one and the working mother. She wants her father to see that.”

It was easy, Beckinsale adds, to get into the father-daughter dynamic because of what De Niro provoked in her. “We all felt that he had this quality that reminded us of our own fathers,” she explains. “It’s not the way he looks or what he does, but he has this mix of strength and vulnerability that reminded everyone – even people momentarily visiting the set – of their dads.”

In a unique twist, Beckinsale’s own daughter, Lily Mo Sheen, plays Amy as a young girl. “Lily always comes with me when I’m working but then I got the call that they wanted her to audition,” recalls the actress. “I thought it might not be a good idea because she has a strong English accent and it’s so difficult to do an American accent. But she aced it and I was like `could you make it look just a tiny bit more difficult?’”

Beckinsale was especially nervous the day her daughter, making her screen debut, had to work directly with De Niro. She recalls: “I was paralyzed with terror for her really… but she was perfectly fine and at the end of it she said, `That was great, I just wish it was with somebody famous like George Clooney.’”

Like Barrymore and Beckinsale, Sam Rockwell, who plays Frank’s son, Robert, was compelled by the story’s probing of the scattered modern family. “It seems these days almost everyone is pretty estranged from their parents,” he observes. “It’s a common thread, so this is kind of a soul-searching movie.”

Rockwell, known for his iconoclastic performances in such films as “Confessions of A Dangerous Mind,” “Match Stick Men,” “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford,” and “Moon,” was intrigued by Robert – who has made it well in to adulthood without his father even really knowing what he does for a living. “Robert has kind of kept his whole life secret,” he muses. “His father got the impression from his mother that Robert was a composer and conductor and Robert just let that continue, but he is really a percussionist. He has been trying pretty successfully to stay aloof from his family for years when Frank arrives.”

Robert is also the first of the Goode children to tell his father that they don’t exactly view their childhoods as ideal. “He’s the first one to spill the truth to Frank and confront him in a real way,” he says. “But even Robert lies to his father about their brother, David. They are all trying to protect their dad from what they fear could destroy him. But I think they begin to see there is also a point when trying to protect your parents goes too far.”

Says Glynis Murray of Rockwell’s performance: “We’ve seen him be funny and scary and be very, very powerful, but I don’t think we’ve ever seen him do this kind of introspective role, playing a person who is so sensitive. It’s pretty different and I think it’s a great part for him.”

Barrymore, Beckinsale and Rockwell, along with De Niro, developed tight bonds as production got under way, and Jones’ made sure the relaxed atmosphere transferred to set. His decision to shoot on a digital format meant that he was able to let the camera run and he encouraged the actors to run straight into repeat takes instead of cutting as he would have done on film.

“Everybody loved the fact that we could let the actors improvise and just roll on, without having to cut,” he explains. “The actors were able to get into a rhythm that feels very true to family life. The only downside with shooting so much is that you have to spend more time in the cutting room selecting. I watched dailies for three weeks solid, 12 hours a day after the shoot to make sure I had selected the very best takes.”

The Journey

When Frank Goode sets out to see his four adult children he finds something that he never realized he’d lost: his family. Frank quickly realizes that his wife’s love for him was so great that she felt a need to protect him from worrying about the details of his family’s lives, the things that she knew he would only worry about.

On his journey, with time to reflect and strangers to expose him to broader conversations, Frank starts to realize that if his children are to be more honest with him, if they are to start talking to him more often and sharing the bad news as well as the good, then he has to start changing himself.

At the heart of the film is an emotional and physical journey. Jones says, “I wanted to be clear that although Frank takes pictures on his journey, a journey of discovery is much more than a collection of photographs, it is about change, about being exposed to unfamiliar situations and to strangers who have views of the world that are different to your own.”

“We had a logistical challenge in that the film had to be shot in Connecticut – in order to take advantage of financial tax breaks being offered by the state – so we had to work out how one single state could appear to accommodate a journey across the whole of the United States.”

“I knew that I already had part of this solution in place. When I traveled across the country I was trying to settle on an occupation for Frank whilst at the same time trying to work out how I could incorporate the stunningly breathtaking landscapes that I photographed. I was looking out of an Amtrak window traveling from St. Louis to Kansas City when I became aware of the telephone wires rolling up and down in front of me. I realized that there was a delicious irony in the fact that Frank could have helped manufacture telephone wire that helped millions of people communicate with each other but that he had trouble communicating with his own family.”

“In addition, I noticed just how many telegraph poles there were and started to see them crossing the most stunning landscapes so I knew that I had a dramatic reason to justify shooting landscapes that feature poles and wires and conversations relevant to the development of the story. ”

The poles and landscapes were shot across country with a small second unit and Jones found himself revisiting cities and states that he had first encountered on his first cross country journey. “It was strange returning to locations that I had visited on a Greyhound bus but was now revisiting with a film crew. ”

The addition of the poles and landscapes helped the film breathe and gave the impression of travel but Jones was also faced with the challenge of making Connecticut look like a dozen states. To do this, he asked his creative team – headed by cinematographer Henry Braham, who worked with Jones on “Waking Ned Devine” and “Nanny McPhee,” and production designer Andrew Jackness (“Killshot”) – to help him not only sell New England as the whole of the US but also to create a story that feels viscerally like a journey.

Explains Braham, “The theme of this film is not only how parents and children relate to each other but very much about a man moving from isolation to reconnecting. It’s a road movie, in a way, so the settings around the characters in each frame were very important.”

Braham and Jones made the decision early on to shoot the film using brand new digital technology – the high-end Panavision Genesis camera. “We were keen to make a movie about contemporary America so that meant shooting it in the most contemporary way,” Braham notes. “It had a huge impact on how we made the movie and on the style and feel of the movie. It allows you to take ordinary situations and urban exteriors and make it all look really beautiful. Kirk took a real leap of faith in shooting the movie digitally, but I think we both have found it visually exciting.”

“The digital format not only allowed us to use traditional film lenses which helped with a film look but it required a fraction of the light that 35mm film requires. This meant we had less prep time on locations and more shoot time and it also meant that we could move quicker as a unit. With regards to the end result we were able to capture stunning scenes using little more than natural light even after dark. We shot in bus stations and subways and in rocky valleys long after the sun set and the results were almost grainless, natural scenes,” recalls Braham.

Part of that visual excitement for the cinematographer was simply shooting the landscape of Robert De Niro’s face. “It’s particularly interesting to look at his face because you can see right through to what he is feeling at any given time,” notes Braham. “The camera loves De Niro because there’s never a moment when there isn’t something in his eyes that you want to watch. He’s completely engaging.”

While Braham’s team eventually went out on a three-week expedition to capture landscapes from the four corners of America, the film’s dramatic action was shot entirely in the state of Connecticut. This gave production designer Jackness, whose work on the screen is influenced by his extensive design work for theatre and opera, an intriguing creative challenge.

“It was very important to the storytelling to create a distinct sense of where Frank is as he travels cross country,” explains Jackness. “My job was to tie together some 60 different locations into a single visual thread as Frank goes from his from East Coast home to New York City to Chicago to Denver and Las Vegas and back again. The idea was to have each world be separate yet to pull them all together into something unified.”

Jackness started by looking through Jones’ famous series of photographs from his research trip across the U.S. – and by getting to know Frank Goode. “The thing that really struck me about Frank in the script is that he’s completely isolated in his environment. He starts out in his garden, where he tends to his own sense of perfection, and when he heads out on this trip he is strangely disconnected from the world around him, until that ultimately begins to shift,” he says.

He also worked closely with Jones and Braham in coming up with a color palette. “We use very neutral, warm tones because Frank is very neutral – he’s a man in search of his relationship with the world – but with these brilliant, little pops of color coming through every once in awhile. It points out the contrast between what’s happening in the landscape and what’s happening inside Frank. The digital technology we used allowed us to make color adjustments as we were filming which was really exciting. Blues became brighter and blacks became sharper and that worked extremely well,” says Jackness.

For Frank’s home, the production temporarily moved into a house that had just come onto the market. “It was better than a set because we were able to paint it and wallpaper it and give it the character it would have had with a couple that had lived there for decades and raised four children there,” he says.

Each of the Goode children’s houses tells its’ own story as well. Explains Jackness, “With David, we tell his story almost entirely with a façade, a hallway and an empty apartment that gives his story poignancy. Amy, in Chicago, has this spectacular house and yet there’s also something alienating about it. Robert is seen in an orchestral hall in Denver and confronts his father on stage in the most dramatic of settings, and Rosie takes Frank into a very Vegas world that doesn’t seem quite real, because it isn’t.”

Throughout production, Jones kept the emphasis on a design that keeps the Goode family’s bonds of humor and emotion in focus. Executive producer Callum Greene summarizes, “Kirk put together a team that brings something different than the run-of-the-mill to every element of EVERYBODY’S FINE. In addition to Henry Braham and Andrew Jackness, we had our costume designer, Aude Bronson-Howard – who has worked with De Niro since `Angel Heart’ and has impeccable taste – and was the perfect person to outfit Frank for this journey. Another key member of the team is editor Andrew Mondshein whose work with Lasse Hallstrom has been so stunning. The feeling among all the cast and crew was really great in large part thanks to Kirk, who is demanding but appreciative, and gave the entire production a real kind of family spirit.”

The Music: Dario Marianelli and Sir Paul McCartney

When it came to the film’s music, Kirk Jones was thrilled to be able to bring to the proceedings both an Oscar winning composer and a legendary pop star: Dario Marianelli (“Atonement,” “The Soloist”) wrote the film’s emotionally rich original score, and Sir Paul McCartney wrote the original song “(I Want To) Come Home” for the film, orchestrated in collaboration with Marianelli.

McCartney has written very sparingly for the movies, outside of the films in which he starred as a member of the Beatles. Most famously, he penned the classic pop hit “Live and Let Die” as a James Bond theme. “I’ve not done it often at all, so this is pretty unusual for me,” McCartney admits.

At first, McCartney was drawn to take a look at EVERYBODY’S FINE simply because it starred Robert De Niro. But when he saw the film, he instantly felt a kinship with the character of Frank Goode that sealed the deal. “I’ve got three kids who have each got their own families,” McCartney explains. “What happens is that when they’re younger and you say let’s get together for the holidays everyone says `yeah’ but as they get older, everyone’s got their own husbands, their own children, and suddenly they want to spend time on their own and as a father you’ve got to deal with that. So I completely related to Frank and to the movie.”

For McCartney, that first showing of the film ultimately led to a flurry of ideas. “The funny thing was, when I saw the film originally, I was just watching the film and enjoying it, when at the end I found that the director had, unbeknownst to me, put in the place where he wanted the new song another song of mine: `Let It Be’ sung by Aretha Franklin. I thought `Oh yeah, top that!’ It was a bit intimidating,” he quips. “I kind of left the theater thinking well, I can’t write another `Let It Be’ and I can’t sing like Aretha much as I want to, so I might have to pass. But that evening, I came back from dinner and started doodling with some chords and I had an idea and it all grew from there.”

McCartney continues: “I try to do music and lyrics together, starting with a rough idea of what might work. I started with this little bit of music and the line `For so long, I was out in the cold’ and then I just developed it from that, words and music, just following the trail. That little beginning of the verse was what led me forwards.”

When the song was completed, McCartney began collaborating with Dario Marianelli on the arrangement and recording. “Originally, the song was very simple: just me and piano, with some bass and drums. But I thought it could use some orchestration so I met with Dario because I’ve enjoyed his work and it made sense to hark back a bit to his score,” McCartney explains. “I went to Dario’s house and we got on very well and we decided to just throw everything at it and see what happened. At first, we threw too much at it, so then we simplified it, using solo string instruments before we went to a full chamber orchestration, which made it a bit more intimate.”

McCartney was thrilled to sit in on the recording sessions. “I consider it one of the great luxuries of life to sit in a room and listen to an orchestra so the recording of it was very exciting for me,” he muses.

Also exciting for McCartney was becoming part of the film world again with his work for EVERYBODY’S FINE. “I’ve loved film all my life and I think a song can have a lot of impact on a film,” he says. “Dario’s score for the film is very emotional so hopefully my song, coming at the end of what is already a very moving film, will heighten the peak of those feelings and put the final little part of the film’s jigsaw puzzle in place.”

Everybody’s Fine (2009)

Directed by: Kirk Jones

Starring: Robert De Niro, Drew Barrymore, Kate Beckinsale, Sam Rockwell, Lucian Maisel, Damian Young, Melissa Leo, James Frain, Katherine Moennig, Chandler Frantz, Lily Mo Sheen

Screenplay by: Kirk Jones

Production Design by: Andrew Jackness

Cinematography by: Henry Braham

Film Editing by: Andrew Mondshein

Costume Design by: Aude Bronson-Howard

Set Decoration by: Chryss Hionis

Art Direction by: Drew Boughton

Music by: Dario Marianelli

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for thematic elements and brief strong language.

Distributed by: Miramax Films

Release Date: December 4, 2009

Views: 169