Tagline: When the world closed its eyes, he opened his arms.

Hotel Rwanda movie storyline. In 1994, some of the worst atrocities of the twentieth century took place in the central African nation of Rwanda — yet in an era of high-speed communication and round-the-clock news, the events went almost unnoticed by the rest of the world. Over one hundred days, almost one million people were brutally murdered by their own countrymen.

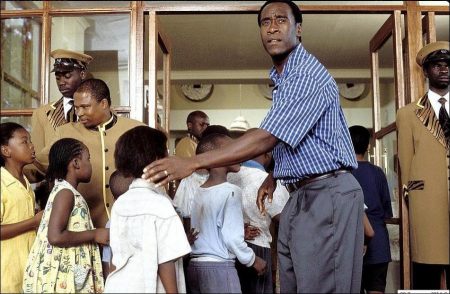

In the midst of this genocide, one ordinary man, a hotel manager named Paul Rusesabagina — inspired by his love for his family and his humanity — summoned extraordinary courage and saved the lives of 1268 refugees by hiding them inside the Milles Collines hotel in Kigali. Hotel Rwanda is Paul’s remarkable story.

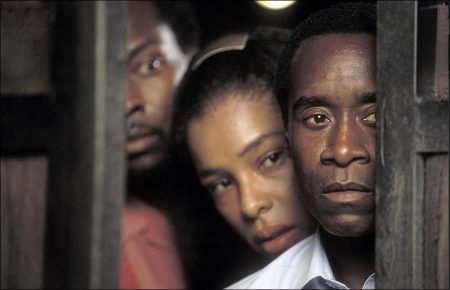

Hotel Rwanda is a 2004 British-Italian-South African historical drama film directed by Terry George. It was adapted from a screenplay written by both George and Keir Pearson. It stars Don Cheadle and Sophie Okonedo as hotelier Paul Rusesabagina and his wife Tatiana. Based on the Rwandan genocide, which occurred during the spring of 1994, the film, which has been called an African Schindler’s List, documents Rusesabagina’s acts to save the lives of his family and more than a thousand other refugees by providing them with shelter in the besieged Hôtel des Mille Collines.[3] Hotel Rwanda explores genocide, political corruption, and the repercussions of violence.

Principal filming was shot on location in Kigali, Rwanda and Johannesburg, South Africa. Paul Rusesabagina was consulted during the writing of the film. Although the character of Colonel Oliver played by Nolte is fictional in nature, the role was inspired by the UN force commander for UNAMIR, Roméo Dallaire. Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni, then-Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana, and Rwandan Patriotic Front leader (now president) Paul Kagame appear in archive television footage in the film.

The producers of the film partnered with the United Nations Foundation to create the International Fund for Rwanda, which supported United Nations Development Programme initiatives assisting Rwandan survivors.[ “The goal of the film is not only to engage audiences in this story of genocide but also to inspire them to help redress the terrible devastation,” said George.

Director’s Statement

Three years ago Keir Peirson and I sat around a table with Paul Rusesabagina and listened as he told us his story. As he spoke, I did my best to hide two conflicting emotions: excitement and fear. Excitement because it was a perfect story to be told on film – a riveting political thriller, a deeply moving romance, and, most of all, a universal story of the triumph of a good man over evil. But fear was my predominant emotion. Fear of failure.

This was a story that had to be told, a story that would take cinema-goers around the world inside an event that, to all our great shame, we knew nothing about. But more than that, it would allow audiences to join in the love, the loss, the fear and the courage of a man who could have been any of us – if we ever could find that courage. I knew if we got this story right and got it made, it would have audiences from Peoria to Pretoria cheering for a real African hero who fought to save lives in a hell we would not dare to invent.

It was a very scary challenge for all of us involved with Hotel Rwanda, but that same challenge seemed to invigorate everyone who worked on the film, from our great cast and crew to the extras who rose at dawn in Johannesburg’s townships of Alexandra and Tembisi to join us in telling this enormous story. I’m proud of everyone who worked on this film and honored to have had the chance to tell the story of Paul, Tatiana, their family, and the people of Rwanda. I only hope to have done his heroic deeds justice.

A Modern Genocide

The Rwandan conflict of the 1990s marked one of the bloodiest chapters in recent African history. The genocide was made all the more tragic by the fact that most of the world chose to ignore the conflict and the plight of the Rwandan people. While occasional reports about “tribal warfare” in Rwanda were carried by international news agencies, the horror of the conflict, instead of causing international outrage, seemed to be written off as another “third world incident” and not worthy of attention.

Over the course of 100 days, almost one million people were killed in Rwanda. The streets of the capital city of Kigali ran red with rivers of blood, but no one came to help. There was no international intervention in Rwanda, no expeditionary forces, no coalition of the willing. There was no international aid for Rwanda. Rwanda’s Hutu extremists slaughtered their Tutsi neighbors and any moderate Hutus who stood in their way, and the world left them to it.

“Ten years on, politicians from around the world have made the pilgrimage to Rwanda to ask for forgiveness from the survivors, and once more the same politicians promise ‘never again,’” says director Terry George. “But it’s happening yet again in Sudan, or the Congo, or some Godforsaken place where life is worth less than dirt. Places where men and women like Paul and Tatiana shame us all by their decency and bravery.”

Wars have always provided fertile ground for the emergence of heroes and supreme acts of heroism by ordinary people. Rwanda was no exception. Amidst the horrendous violence and chaos that swept the country, one of the many heroes to emerge was Paul Rusesabagina, an ordinary man who, out of love and compassion, managed to save the lives of 1268 people.

Terry George had long been interested in doing a film set in Africa, but it was Paul Rusesabagina’s story that finally brought him to the continent. “When my co-writer Keir Peirson introduced me to the story, I immediately knew I wanted to do it,” says George. “I flew to Belgium and met Paul and learned of his life: how he became a hotelier, how he rose through the ranks of employees in the various Sabena hotels he worked in, and how he ended up at the Hotel Mille Collines in Kigali.”

It was the remarkable human element of the story that struck a chord with Hotel Rwanda producer Alex Ho. “This story is very close to my heart, and it’s the kind of story I really appreciate,” he says. “It’s about a normal man who, when prompted by his wife, is able to use his position to help others. In the course of doing that, he sets out on a journey that makes him a better man.”

Homage to A Brave Man

In January 2003, Terry George traveled to Rwanda to research the story and familiarize himself with the country. “I was also looking for answers,” says George. “Why the genocide? Why were so many people murdered in the space of 100 days, the fastest genocide in modern history? I also wanted to get a sense of the ordinary people of Rwanda and listen to their stories. George was accompanied on his visit by Paul Rusesabagina. It was the first time Paul had returned to Rwanda since the atrocities.

While in Rwanda they were able to travel, film the various locations and meet many of the people who took refuge at the Milles Collines hotel, including Odette Nyrimilimo, her husband Jean Baptiste Gacacere, and various members of Paul’s family. “It was a unique privilege to visit Rwanda with Paul,” says George, “to get a sense of the love and admiration people had for him. When we walked back into the Hotel Mille Collines, we met many of the survivors, cooks, cleaners, people Paul had sheltered. There was true joy in their eyes.”

Though many of George’s experiences in Rwanda were positive and he took inspiration from the many people he met, nothing could have prepared him for what he experienced when visiting one of the massacre sites. “We paid a visit to a former technical college at Marambi in Southern Rwanda,” says George. “I passed through rooms filled with the mummified skeletons of some of the 40,000 people who were massacred over four days in April 1994. As I listened to the sole survivor of that massacre tell of those days, I truly felt there was nothing more important in my life than to make this film.”

In visiting Rwanda, George was also able to see the incredible beauty of Rwanda and to investigate the politics of the extremist Hutu government, how their radio station RTML spewed forth hate and venom towards the Tutsi and how prejudice and fear drove ordinary people to believe that they had to massacre their neighbors in order to preserve their existence. “If I had ot point to the one factor that sparked this genocide,” says George, “it was that radio station. We feature that radio station as a character in the film. I need people to understand the power of that propaganda.

When adapting Hotel Rwanda for the screen, it was important to George and Peirson that the film not be structured or perceived as a documentary, but rather an emotional distillation of the events and facts of Paul’s life that gives the audience an intimate, insider’s view of the events that took place at the Hotel Mille Collines at the time. “I find it most important to tell a story based on character and the evolution of that character, as well as the strengths of the character,” says George. “We have highlighted the particular events that formulated his triumph – his ability to succeed in the face of overwhelming odds. I enjoy my work best when it’s a project that will enlighten and hopefully invigorate people.”

Hotel Rwanda is, for the most part, a deeply personal story, and it’s uniquely focused on one building (the hotel), the people within it, and the relationships between them. The filmmakers deliberately avoided focusing on the overwhelming horror of the genocide itself.

“When the film ventures outside into Kigali during the genocide, we tried to create this bizarre, surreal atmosphere, to let viewers feel the psychological terror of the genocide without going close on the slaughter.” Says Alex Ho, “This is a powerful human drama, not a horror story, and we believe it is important that the widest possible audience should see it.”

Hotel Rwanda (2004)

Directed by: Terry George

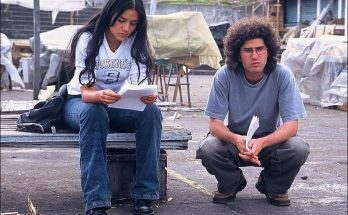

Starring: Don Cheadle, Joaquin Phoenix, Sophie Okonedo, Nick Nolte, Antonio David Lyons, Xolani Mali, Fana Mokoena, Leleti Khumalo, Jeremiah Ndlovu, Rosie Motene

Screenplay by: Terry George, Keir Pearson

Production Design by: Johnny Breedt, Tony Burrough

Cinematography by: Robert Fraisse

Film Editing by: Naomi Geraghty

Costume Design by: Ruy Filipe

Set Decoration by: Flo Ballack

Art Direction by: Emma MacDevitt

Music by: Afro Celt Sound System, Rupert Gregson-Williams, Andrea Guerra

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for violence, disturbing images, strong language.

Distributed by: Metro Goldwyn Mayer

Release Date: December 22, 2004

Views: 85