Finally, Cameras Roll On the First Indiana Jones Adventure for a New Generation

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull Movie Trailer movie storyline. Following tradition on his movies, director Steven Spielberg broke out bottles of Champagne and offered a toast as cameras got ready to capture the first images of “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.” “It was like we dropped back to the end of the last one,” says producer Frank Marshall. “It was exactly the same. The relationships, the creative atmosphere that was on the set, the respect – all these elements were there once again.”

“There wasn’t one person there who didn’t believe they were witnessing magic,” says co-producer Denis L. Stewart. “Everyone was so happy and full of adrenaline just to see everyone together again making these movies. That carried the day and helped us move through an aggressive schedule.”

The first leg of production unfolded in the stunning and desolate desert landscapes of New Mexico. From Ghost Ranch, the company traveled 300 miles southwest to Deming. There, hangers at an old World War II Army Air base were virtually unchanged since their heyday, and with a little set dressing and some War-era army Jeeps and Soviet soldiers, the area was transformed to provide the backdrop for the opening sequences of the movie.

From New Mexico, production traveled east to the home of Professor Jones and Marshall College. “One of the challenges we had on this movie,” Marshall explains, “was that we had established a lot of locations in the first three movies which we had to duplicate.” Indeed, the interior of the classroom in “Raiders of the Lost Ark” was shot in London, while the exterior was shot at the University of the Pacific in Northern California. For “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull,” the filmmakers would need to reproduce both. The solution, says Marshall, was found at an iconic Ivy League school in New Haven, Conn.

The filmmakers were delighted to find the unique personality and flavor for Marshall College at Yale University. “The exteriors were perfect for the period, the classrooms were great and we had wonderful cooperation from the university and the town,” Marshall says. From the classroom to a motorcycle chase through campus halls, quads and town, Yale and New Haven provided a perfect backdrop for Professor Jones, Dean Stanforth and the introduction of Mutt.

As the film’s producer, it was easy, in the midst of production, to forget that Indy’s workplace had a very familiar name. “I started seeing `Marshall’ everywhere when I got to New Haven’ and then I realized that, way back on `Raiders,’ we had come up with the incredibly inventive name of Marshall College,” he jokes.

Some of the most critical and challenging sequences in the story take place within the dense jungles of the Peruvian rainforest. “Iquitos is referred to as the `Gateway to the Amazon,’” says screenwriter David Koepp. “It’s the last city before you move into intense jungle, the border where the wild and the civilized meet. It’s the perfect place for an Indiana Jones adventure to begin.”

In a small town at the jungle’s entrance, Indy and Mutt locate important clues that draw them deeper into the mysteries of the Crystal Skull. While the exterior of the town was shot on the Universal backlot transformed by production designer Guy Hendrix Dyas into a dusty Peruvian street, the jungle itself was a more difficult find. The filmmakers scouted far and wide for an ideal location that would reflect that primeval forest.

“It’s hard to find untouched jungle,” co-producer Stewart says. “We searched Mexico, Guatemala, South America, Puerto Rico.” Finally the production found what they were looking for a little closer to home. “We looked all over for the right location, and finally decided to look at Hawaii.”

The company found their jungle in the southeast corner of the Big Island of Hawaii. On a private tract of land, under the dense canopy of old jungle growth, the filmmakers spent several weeks filming some of the more challenging sequences of the film, including a swordfight atop moving cars.

“The Hawaii location became an excellent place for us to pull off some very difficult scenes,” says Marshall, “We had a lot of action, a lot of stunts with the actors themselves, so it was important to be in a place where we could pretty much operate without any outside interference.”

From Hawaii, the company traveled back home to Southern California and resumed shooting, using nearly every studio lot for dozens of vast and varied sets skillfully crafted by Dyas and his team.

Indiana Jones’ home was built on Stage 29 on Universal Studios’ famous backlot. “It’s one of those archetypal sets that allowed us to show our main character’s more private side,” says Dyas. The production designer and his team worked hard to replicate Jones’ home, carefully pouring over images from the previous films. “We meticulously tried to recreate the style of Indiana Jones’ 1930’s home interior while keeping in mind the fact that we’re now in 1957,” says Dyas. Working with set decorator Larry Dias, Dyas sought to create a home that would both reflect Indy’s personal style and interests and convey to the audience a real sense of passage of time since the last film. “We filled his living room and study area with beautiful & intriguing archaeological artifacts, objects that Indy has collected over the years during some of his other faraway adventures.”

Dyas’s team also created several exterior sets at Universal Studios, including the dangerous town where Indy and Mutt land on the first leg of their journey; and a massive, nearly 80-foot-tall, structure that’s part of the temple seen in the film’s climax.

A disappearing “stone” staircase built around a 35-foot cylinder went up on a soundstage on the other side of Los Angeles, at Sony Studios, formerly the legendary MGM backlot. The task of creating practical stairs that would retract as our heroes swiftly make their way down, fell to special effects coordinator Dan Sudick. (As opposed to the visual-effects work of Industrial Light & Magic, “special effects” refers to practical effects created on set.)

Sudick had handled special effects on Spielberg’s “War of the Worlds” and the director was so impressed with his work, he invited him back. “I walked onto the set and it was one of the most exciting things I have seen since I walked onto Joe Alves’ set on `Close Encounters of the Third Kind’ in that dirigible hanger in Mobile, Ala.,” recalls Spielberg.

Across the road, Universal’s Stage 27 housed another piece of the production puzzle – a Peruvian cemetery set. It was a large, multi-level construction that would allow the characters to crawl amid dusty ruins and ancient artifacts under the treacherous eyes of the keepers of the cemetery and its secrets. Running from a ghoulish mob, Indy and Mutt make their way down to the deepest part of the pit that links up to another set built 20 miles away in Downey, California.

At Downey Studios, a number of sets were erected in a massive hangar that, at more than 600,000 square feet, once served as a home to the development of the Apollo spacecraft and the Space Shuttle. Downey would serve as the home of several notable sequences in “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” – among them, a series of cave tunnels in which portions of the adventure unfold, and an experimental military-style bunker that’s related to another location filmed in New Mexico.

A 1950s diner, inspired by the Edward Hopper painting Nighthawks, was built on Paramount’s sprawling backlot, augmenting scenes filmed in Connecticut.

Of all the sets, one stood out as being of particular interest to longtime fans of the Indiana Jones movies: the warehouse. Twenty-seven years ago, it was created with the help of a detailed matte painting and great camera trickery, but in “Kingdom of the Crystal Skull,” Spielberg wanted to bring to life his matte painting. “I still remember watching that last scene from `Raiders of the Lost Ark, as a kid,” says Dyas, “and wondering how they did it. Little did I know that one day I’d be having real conversations with Steven Spielberg and George Lucas about it, it was very exciting to try and capture the spirit of that scene from the very first Indiana Jones film.”

On the Warner Bros. lot, the production took over the massive interior of Stage 16 to build some of the most elaborate sets for the climax of the film.

“Guy had a tremendous challenge because we wanted to do all the sets for real,” says Marshall. “He had to build sets that looked ancient, had history behind them, were scary and foreboding – and then had to put them on stages all around Los Angeles. We couldn’t do the whole movie on one lot, like we did in London with the other three, so for the first time in my career, we were on five different studio lots, which may be some sort of record.”

Despite their disparate locations, walking around on Dyas’s sets gave Spielberg a familiar thrill. “I’d walk on each set and say, `I’m on the set of an Indiana Jones movie – how lucky am I that I get to direct another one of these?!’”

Skulls, Whips and Leather Jackets

Intricately Designed Props and Costumes Bring Indiana Jones to Life

There can’t be more iconic imagery than that, and it proved a challenge to the talented team assembled to create the props and costumes for “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.” From Indiana Jones’ whip and fedora to Mutt’s biker jacket, they had a complex task of creating a new and yet still familiar world.

Costume designer Mary Zophres, co-costume designer and collaborator Jenny Eagen and costume designer for Harrison Ford, Bernie Pollack, had a challenging balancing act of hewing closely to the look of the first three films while adding new touches. The era provided no shortage of inspiration in the creation of new characters. Producer Frank Marshall explains, “Each of our new characters has been inspired by the `50s, and Mary seemed to have a terrific time creating the look of these characters.”

Zophres pored through old Life magazines, 1950’s college yearbooks, vintage Russian military handbooks, photos of Mayan ruins and history books to get inspiration for the design of “Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. “I got every yearbook I could get my hands on from the Northeast, and from Yale in particular,” she says.

For Zophres, who received a BAFTA nomination for her costumes on Spielberg’s 1960s-era film “Catch Me If You Can,” the thrill of designing costumes for the film was partially derived from the enthusiasm of the director. “His body of work means a great deal to me, so when I make him excited and enthusiastic, it’s very rewarding. When you make Steven smile it makes your day.”

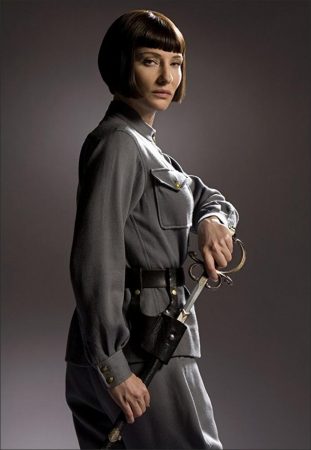

Zophres had her work cut out for her. She had to develop a signature look for femme fatale Irina Spalko, and to do it, Zophres took inspiration from 1930s screen siren Marlene Dietrich. “She had a lot of charisma with a certain amount of edginess and toughness, which I thought would be appropriate for Spalko,” Zophres explains. She and her team found a stock of genuine Russian military uniforms to dress Spalko’s nefarious crew. “I almost had a heart attack when we found them, but they were only in size 40 and 42, so we found fabric, dyed it to match and then made the rest of the sizes for all the other Russian soldiers,” she says. “But we found the real thing. You open up the jackets and there’s a real Soviet stamp inside of them.”

For the return of Marion Ravenwood, Zophres drew inspiration from a previous era, incorporating the look of 1930s adventurers like Amelia Earhart. “Marion’s a little bit of a tomboy,” Zophres explains, “but extremely courageous, beautiful and feminine at the same time.”

For Mutt, Zophres helped actor Shia LaBeouf express the character through a rebel “uniform” of leather jackets and motorcycle boots. “Mutt was inspired by Marlon Brando in `The Wild One,’” says Zophres. She and co-costume designer Jenny Eagen found authentic vintage motorcycle jackets and had LaBeouf try them all on until they found the one they liked best – then they recreated it to have the multiple versions they would need as the on-screen adventure progresses. “We had to make about 30 of those motorcycle jackets, because Shia does a lot of stunts and his costume got worn and dirty,” Zophres says.

The far-flung inspiration for the movie’s characters continued with Mac, played by Ray Winstone. “Mac has one of my favorite costumes in the movie,” Zophres says. “There’s this picture I have of Ernest Hemingway, and he’s got his foot kicked up in the air with these great high boots on. I found a pair of these high boots with this really interesting sole, so Mac wears his pants tucked in and he’s rocking those boots through the whole movie.”

As if Zophres’ hands weren’t full enough, she and Egan also had to create costumes for the scores of extras that populate the film, including more than 200 in the sequences set in Peru – for which Zophres had to send a buyer to the South American country itself and bring back textiles to use when making the costumes. “Because it’s a story that travels the globe, I wanted to go there with the costumes as well. We achieved that through changes in color palettes and stylistic differentiations, giving each locale a distinctive look.”

Pollack, who has worked with Ford for 15 years, went on an odyssey of his own to recreate – and update – Indy’s wardrobe, both as an academic and as an adventurer. “Bernie took Indiana Jones as he was in the earlier movies and then stepped him up into the Fifties,” Marshall says. Pollack says some of his task was easy. “Indy is a classic guy who sets his own style and has his own look, and doesn’t change it.”

As it turned out, Indiana Jones wasn’t the only person who hadn’t changed much in the time between. “I hadn’t worn the Indiana Jones costume for 18 years,” says Ford. “Bernie sent that original costume to my house for me to try on, to see where we would have to change sizes. I put it on and it fit like a glove. I felt really comfortable and ready to go!”

While Indy may only seem to wear one costume on screen, in reality, Pollack ultimately had to make 60 pairs of pants and 72 shirts. He also decided to make Indy’s jacket slightly bigger, in order to accommodate the padding Ford would need when doing his stunts. Using stills from the original films, he meticulously designed the instantly recognizable leather jacket, then searched for someone who could make it. That search spanned the U.S., the U.K. and Europe. Finally, costume supervisor Bob Morgan brought in a leather clothier named Tony Novak from El Segundo, Calif. Novak said he needed only a sample jacket to make a prototype overnight. But the Lucasfilm Archives, which had kept the original jacket safe for more than two decades, required tight security; Pollack had an assistant accompany the jacket to Novak’s offices.

“About nine o’clock that night, the jacket was back,” Pollack says. “And it was perfect. I couldn’t believe it. So, I asked him to make 30 of them! I love that guy.”

Recreating the famous fedora was more difficult. Pollack worked his way through numerous designs, multiple fabrics and scores of hatmakers. While he seemed to find the right haberdasher in Germany, the quick turnaround was daunting – Pollack had only a month to have someone make and ship the hats to the set. That’s when Pollack’s German contact suggested Steven Delk of Adventurebilt Hat Company in Columbus, Miss.

“Steven ended up making a lot of different hats, and refining them until he came up with exactly the perfect hat,” Pollack recalls.

Award-winning prop master Doug Harlocker’s job encompassed finding, buying or making everything from bullwhips to mummies, motorcycles to llamas. And while procuring the wide range of things that fall under the umbrella of film props, Harlocker worked to remain true to the film’s legacy while introducing a few new things.

“We constantly talk about how to reprise little things from the previous movies that the audience would enjoy discovering,” says Kennedy. “Doug Harlocker has done a great job bringing in several things from the previous movies that the audience can have fun with and, at the same time, he’s contributing all sorts of new ideas.”

For “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull,” Harlocker and his team assembled a treasure trove of goodies including a Bobber-style motorcycle for Mutt, AK47s and Tacarov pistols for the Russians, a cache of fencing swords, a barn house of animals and, one other indispensable “prop.”

“Indiana Jones’s one weakness is an absolute pathological fear of snakes,” says Harrison Ford. “So, of course, we had to have snakes.”

When shooting “Raiders of the Lost Ark” in 1980, he recalls, “there were laundry tubs of snakes. In one of those containers, you can put maybe 8,000 snakes. We had dozens of these containers in the original scene in the temple in the first `Raiders.’”

Luckily, there’s only one snake in “Kingdom of the Crystal Skull.” But it’s a doozy: a giant Olive Python. “We had the requisite snake, a beautiful snake to us but not to Indy, of course,” Spielberg says with a laugh. “It was a rather large python. The audience wouldn’t forgive us if we didn’t have at least one snake in the movie.” In addition to the real snake (two for shooting purposes), Stan Winston’s studio worked with Harlocker to create a perfect replica out of rubber.

With the help of the Lucasfilm Archives, Harlocker was able to pull together samples of all the original props and build on them. Indiana’s personal items included the whip, the haversack, his gun belt, his whip keep, his journals, his father’s pocket watch and his glasses – and while the glasses would evolve for the film, Indy’s haversack would be the very same one he carried through his last adventure.

Harlocker had Indy’s bullwhips custom-designed by an Australian company to be more versatile for Ford. That made re-mastering the fine art of whip-cracking a bit easier for Ford. “It’s a relatively uncommon skill,” Ford says. “And I wasn’t terribly good at it – but I guess I was good enough for show business when I did it the last time. We had a new whip trainer on this movie who had a different technique. So after a couple of weeks of pretty diligent practice, I was able to get it all back.”

Seeing Indy’s trademark bullwhip brought feelings of nostalgia and excitement to everyone on the set, Spielberg says. “To see Harrison walk on the set, pick up the whip, snap it and wrap it around one of the bad guys was pretty incredible,” he says. “It was amazing to see how fast Harrison was with it – and then to be on the set and see Indy’s rucksack and his other props, well, it wasn’t just nostalgia. That was when I realized we’re bringing this character and everything he’s about back to the audience that grew up with him and to new audiences.”

The History Behind the Mystery

Eighty Years of Exploration and Study Reveal the Secrets of Crystal Skulls… Maybe

In 1924, the famed British banker-turned-adventurer F.A. Mitchell-Hedges led an expedition deep into the Central American jungles of British Honduras (now Belize). His mission: to find evidence of the lost continent of Atlantis. But it was Mitchell-Hedges’ adopted daughter, Anna, who made a find for which this quest was to become famous. On Anna’s 17th birthday, as Mitchell-Hedges and his crew were excavating the ancient ruins of a Mayan temple at Lubaantun, Anna spied an object glinting in the soil under a collapsed altar: a beautiful sculpted human skull carved with uncanny craftsmanship out of a single block of translucent quartz crystal.

When she first touched the artifact, Anna reported experiencing strange sensations. And any time she placed the skull near her bed at night, she reported vivid dreams of the Mayan Indians who had lived thousands of years ago, and of their everyday life and ritual sacrifices. According to the few remaining Indians in the area, she said, the skull had been used by the high priest of that culture to will death. Her father asserted the skull was 3,600 years old and dubbed it “The Skull of Doom,” because of its supposed supernatural powers and the misfortune that befell those who handled it.

News of the startling discovery caused a sensation in the art and antiquities world. Subsequently, a number of other crystal skulls surfaced, some of which found their way into museums around the world, while others have remained in private ownership. To this day, speculation about the origins of these artifacts ranges far and wide. Some say the skulls are relics of Atlantis and may have been wrought by space aliens. Believers maintain they are matrices of radiant psychic energy with the power to cast spells, conjure spirits, cure illness and foretell the future.

In many hypotheses, the number 13 features prominently. One such theory maintains that the skulls were left behind by a society that lived at the hollow center of the Earth, and that 13 “master skulls” contain the history of these people. Others theorize that each of the 13 master skulls has a specific property, and that bringing all 13 together will make all these abilities available to everyone at once, thus ushering in a new age.

Most of the other crystal skulls that rose to fame after Mitchell-Hedges announced his discovery are of a more stylized structure, with teeth etched onto a single skull piece, as opposed to the Mitchell-Hedges skull which had a detachable lower jaw. Examples include a pair of skulls – known as the British Crystal Skull and the Paris Crystal Skull – currently on display at the Museum of Mankind in London and the Musée de L’Homme in Paris, respectively. Another pair of famous skulls-the Mayan Crystal Skull and the Amethyst Skull-were reportedly brought to the United States by a Mayan priest.

Two well-known skulls in private collections are nicknamed “Max” and “ET.” Max, also known as the Texas Crystal Skull, reportedly passed from a Tibetan healer to JoAnn Parks of Houston in the early 1980s. The skull gained its nickname after Parks claimed the skull told her its name was Max. The E.T. skull – so named because its pointed cranium and exaggerated overbite make it resemble the skull of an alien – is part of a private collection belonging to Joke van Dieten Maasland, who claims the skull helped heal her of a brain tumor. The only crystal skull with a comparable level of craftsmanship to the Mitchell-Hedges skull is the Rose Quartz Crystal Skull, which also includes a removable jaw, but is slightly larger and not translucent.

But the Mitchell-Hedges skull – weighing 11.7 pounds and standing 5 inches high, 7 inches long and 5 inches wide – remains most famous to this day. In 1970, the Mitchell-Hedges family reportedly loaned the skull for testing to Hewlett-Packard Laboratories – a leading facility for crystal research in Santa Clara, California. The testing produced some startling findings, according to Frank Dorland, an art restorer who claims to have overseen the examinations. He reported that HP researchers found that the skull had been carved against the natural axis of the crystal. Modern crystal sculptors always take into account the axis, or orientation of the crystal’s molecular symmetry, because carving “against the grain” causes the crystal to shatter – even with the use of lasers and other high-tech cutting methods.

Furthermore, Dorland claimed, HP could find none of the microscopic scratches on the crystal typically caused by carving with metal instruments. This led Dorland to hypothesize that the skull was roughly hewn with diamonds, with the detail work being done with a gentle solution of silicon sand and water- a near-impossible task he estimated would have required up to 300 years in man hours to complete. Dorland also claimed the skull originated in Atlantis and had been carried around by the Knights Templar during the Crusades.

But there is no documented evidence to support the claims of the skull’s exotic origins and some authorities have claimed that Mitchell-Hedges purchased the skull at an auction at Sotheby’s in London in 1943 – an allegation supported by documents at the British Museum, which reportedly had bid against him for the artifact. That would also explain why Mitchell-Hedges apparently never spoke of the skull before 1943 – even though he claimed Anna had found it nearly 20 years earlier. However, Mitchell-Hedges claimed he was actually buying back the skull after leaving it in the care of a friend, who put it up for sale at Sotheby’s.

There is also some doubt as to whether the tests at Hewlett-Packard were ever carried out, since no evidence of such testing has been provided by the company. Furthermore, later tests determined that the skull was carved using 19th century jeweler’s tools, making its supposed pre-Columbian origin even more dubious.

But Anna Mitchell-Hedges, who possessed the skull until her death in 2007 at the age of 100, stood by her father’s story and was loyally supported by others who are convinced that the crystal skulls possess important mystical powers.

Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of Crystal Skull (2008)

Directed by: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Harrison Ford, Cate Blanchett, Karen Allen, Ray Winstone, John Hurt, Jim Broadbent, Shia LaBeouf, Jim Broadbent, Dimitri Diatchenko, Ilia Volok, Pasha D. Lychnikoff, Venya Manzyuk

Screenplay by: David Koepp

Production Design by: Kathleen Kennedy, George Lucas

Prodüksiyon Tasarımı Guy Hendrix Dyas

Cinematography by: Janusz Kaminski

Costume Design by: Mary Zophres, Bernie Pollack

Set Decoration by: Larry Dias

Art Direction by: Luke Freeborn, Lawrence A. Hubbs, Mark W. Mansbridge, Lauren E. Polizzi, Troy Sizemore

Mario Ventenilla

Music by: John Williams

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for adventure violence and scary images.

Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: May 22, 2008

Views: 175