Into the Blue Movie Trailer. Director John Stockwell enjoyed considerable success guiding the surfing adventure Blue Crush, which was set amidst the crashing waves of Oahu, Hawaii. A longtime surfer as well as a diver, he found himself drawn once again to work in and under the water when he accepted the offer to helm Into the Blue.

“There was something about going back on to the water, as well as going underwater, that was a real challenge,” says Stockwell, who also directed the romantic drama Crazy / Beautiful. “I thought the script for Into the Blue had real drive and originality. Also, I like being on the water, and 70 percent of this film was designed to take place on or below the waterline.”

After scouting locations in such places as Florida and the Cayman Islands, the filmmakers settled on the Bahamian island of New Providence, home to the colorful capital city of Nassau, as their setting. Although the other areas had their plus points, explains producer David A. Zelon, New Providence brought together all the necessities for an arduous sea-based production.

“We came here for the crystal clear water quality and the sharks, which are in almost every scene,” says Zelon, “as well as for the unmatched beauty of the island and the wealth of skilled workers and actors in Nassau. We wanted a very natural look, and John wanted to use as many Bahamians as he could to create a natural feel for the film.”

One of the first Bahamians recruited aboard was veteran shark and diving expert Stuart Cove, who has brought his underwater expertise to such marine-based productions as Thunderball and Flipper. Even for an old salt like Cove, the demands of Into the Blue at first seemed a bit daunting, he confesses.

“In terms of underwater scenes, the only other movie I can think of that comes close to this was Thunderball,” says Cove, whose dive operation, Stuart Cove’s, is one of the largest in the Caribbean. “But Into the Blue has it all — free diving, sharks, airplanes crashing into the sea, huge fight scenes, and almost half of the filming took place underwater.”

The filmmakers employed many of Cove’s boats as well as his guidance, making use of several of his launches and employees throughout the six months of production. Cove says he was impressed by the film unit’s concern for safety and conservation. “The most important thing for me in taking the job was: ‘Are they going to be environmentally friendly?’” Cove admits. “I’m happy to say that in my 25 years of film work, this has been the most environmentally friendly group I ever worked with. They also hired the most Bahamians to work on the film, which was a boon for the local economy.”

One of Stockwell’s main concerns about shooting underwater was how long his actors could stand the water temperature. Even though the film was set in the temperate seas of the Bahamas, most of the filming took place during the comparatively chilly winter months.

“January through March are warm by moststandards, but the water temperature is only about 70 degrees,” says Stockwell. “That means the actors, especially if they are free diving in board shorts or a bikini, are still going to feel hypothermic after only about 20 minutes in the water. The actors would definitely be suffering for their art.”

The fast growing sport of free diving is similar to snorkeling in that the swimmers wear snorkel masks but closer to scuba diving in that they voyage into deep water for extended periods. Beginners venture as deep as 30 feet for as long as 45 seconds. More “extreme” and experienced divers go much farther down — the current record being 335 feet — for several minutes at a time.

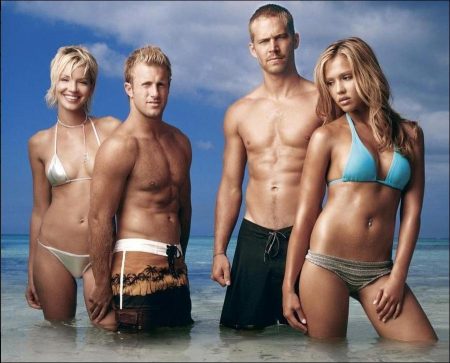

Choosing an athletic cast that would be able to quickly adapt to the largely underwater environment was Stockwell’s most serious task. He was looking for performers who would be at home in the sea and enjoy the long hours of sun and stunts as well. The first actor he approached was Paul Walker, who agreed to play the lead role of Jared Cole even though he knew the pitfalls of working on and in the water. As a lifelong surfer, water skier and free diver who grew up along the beaches of Southern California, Walker knew the role would require a great deal of physical stamina.

“I knew the part would be physically draining,” says Walker. “Seventy degree water may be warm by California standards, but water absorbs body temperature 25 times faster than air. You get the chatters as soon as your body loses two or three degrees of body temperature. I realized we would need long breaks to reheat ourselves. I tried to prepare myself by eating well and getting as much sleep as possible. I also trusted John and knew he would keep everything as real as he could.”

To keep Walker on his toes, Stockwell deliberately chose Walker’s real-life friend Scott Caan to play Jared’s pal Bryce Dunn, because he sensed the two would engage in a great deal of good natured competition both on and below the water’s surface.

“What I loved about Paul and Scott was that they had prior relationship as friends who were naturally competitive,” recalls Stockwell. “They’re really like brothers, but there is an interesting rivalry between them that I tried to foster during the shoot.”

Walker and Caan had previously worked together on the popular high school football film Varsity Blues and had been looking for another co-starring vehicle. Into the Blue was not only an exciting adventure that offered them both strong roles but even better one that offered adventure and unique physical challenges.

“Paul and I have always been very competitive,” admits Caan, “whether it be about girls or sports or whatever. We butt heads because we want to one-up each other, so that meshed perfectly with our characters. And it was amplified once we actually started shooting,” he adds with a mischievous laugh.

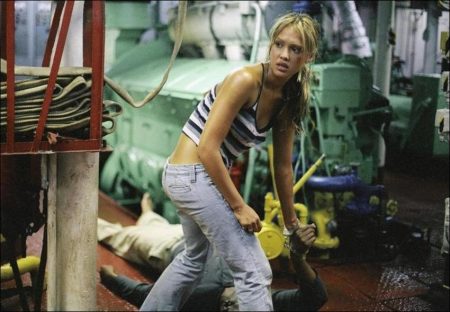

While Walker and Caan were preparing and learning to operate boats, jet skis and diving equipment, co-star Jessica Alba was enjoying a few weeks of brushing up on her diving skills in the nearby Cayman Islands before joining the cast and crew in the Bahamas. The actress had learned to free dive and scuba dive while starring in the television series “The New Adventures of Flipper” in Australia, from 1995-97, prior to her breakthrough role as Max in the hit television series “Dark Angel.”

“I was attracted to Into the Blue specifically because of the water element,” says Alba. “When I was a kid, I used to pretend I was a mermaid. Nowadays, I love swimming, free diving and scuba diving. The underwater world is so serene and private. The ocean is a beautiful fully-contained world that we often forget about in our daily lives.”

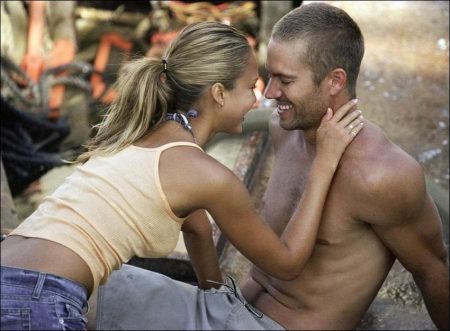

Alba enjoyed working with co-star Paul Walker, with whom she felt an immediate kinship. “We met several months before filming and we got along right from the start,” she says. “We both have been actors since childhood and we grew up in the same area. He surfed with guys that I grew up with. We clicked and became fast friends. I was impressed with how hard he worked and how he helped carry the movie forward as filming went along.”

Two other major cast members that fell into place were Ashley Scott, in the role of Bryce’s new girlfriend Amanda Collins, and Josh Brolin, who would play Jared’s treasure-hunting rival, Derek Bates. Although the athletic Brolin quickly adapted to the rigors of dive instruction, it took Scott a bit more time to feel completely at ease underwater, she admits. “I had never been diving before, only a little snorkeling here and there,” says Scott. “Scott and I started by learning how to scuba dive in a pool. It was like summer camp, with homework and lessons. Then, about two weeks before we started shooting, we went into the ocean with safety divers and did some exploring. I finally became really confident and now that I am a certified diver, I can go anywhere in the world and dive, a huge bonus, as if I needed anything more than getting to shoot a movie in the Bahamas.”

Brolin impressed his co-stars with his adaptability during the several weeks of intensive dive training from the film’s team of professional divers. The actors were schooled not only in scuba gear and diving techniques, but also in holding their breath during free diving and losing their natural fear of the depths.

Sharks, Boats and Sunken Treasures

The storyline of Into the Blue may be fiction, but the craze for underwater treasure hunting is very real. Thus, the Bahamas was a logical choice for filming this story, given that, from the 15th to the 18th century, more than 500 Spanish galleons are believed to have been lost in its dangerous waters — a majority of which have never been found and are said to be laden with billions of dollars in gold and priceless artifacts.

The area off New Providence’s southern coast is well known among divers and sportsmen alike as a shark-sighting paradise. Lurking just offshore is a yawning abyss several thousand feet deep that attracts scores of game fish. And where there are fish, there are sharks – mostly docile Caribbean reef sharks, but also a large population of unpredictable tiger sharks. Both reef and tiger sharks were utilized in the script by screenwriter Matt Johnson (Torque) as an important part of Into the Blue’s storyline.

“We came here in part because of these sharks,” says producer David A. Zelon. “But I don’t think that everyone will believe that these actors actually got in the water close to the sharks. They are going to think these are computer generated. There are many scenes where these sharks come right up and bump our stars. We always had safety people right next to them at all times, but these sharks were always close by and circling them.”

Before the start of principal photography the actors did some full wet rehearsal dives to introduce them and the stunt people to the challenges of working underwater. Beyond fundamental diving-safety protocol and underwater communication techniques, they trained to dive safely with real sharks and learned how to free dive (snorkeling to depth on a single breath of air).

The cast eventually swam 40 feet down among sharks while searching for treasure, communicating with hand signals, and using body language to express themselves. Each actor has his own story about his or her relationship with these deep-sea predators, which they feared at first. But they soon came to respect the sharks and co-exist with them for the duration of the shoot.

“I was petrified of sharks,” recalls Scott. “Always have been, since childhood. On the first day I went into the water, they didn’t really tell me how many sharks would be down there or I never would have dived. When I went down, I saw more than 20 reef sharks swarming in a feeding frenzy. I started to cry. But I quickly got used to them and, if you can watch them from a safe place, they are very beautiful.”

Caan also had to overcome his innate fears, especially during the filming of a scene in which he has to fend off a shark on the open sea with nothing but a mop on the open sea. “I grew up surfing, and sharks were always bad news,” Caan recalls. “These sharks were coming right at me. They were snatching the mop handle right out of my hands with mouths the size of a motor block. I was never totally comfortable with them.”

Walker and Alba also had close encounters with reef sharks in the movie. Walker’s character, among other things, is swarmed by feeding reef sharks as he tries to get into skin-diving gear while bobbing in the water. “I had seen sharks while diving in spots like Fiji, Hawaii and Costa Rica,” says Walker. “But I had never seen so many in one place. They’re wild animals and you have to be leery of them, even when you have safety divers around you. In this scene I am treading water and these sharks are boiling all around me. They bump you a lot, so you can only kick them off the best you can. I must have had 30 sharks around me. It was very intense.”

Alba’s character, Sam, is a professional shark handler at the Atlantis Resort in Nassau, so the actress spent a great deal of time learning how to deal with sharks by actually feeding them on camera in several scenes. She shot a sequence in the Atlantis’ shark pool in which she hand feeds scores of nurse sharks, who are generally not dangerous biters. Still, Alba paid close attention to the instructions from the resort’s shark handlers so she would be sure to complete her scenes with all her fingers and toes intact.

“You have to be aware of your hands and feet,” she says, “and pray the sharks don’t mistake you for a fish. I’m the one in their territory and they are going to do what they want to do. What I learned is that the sharks don’t care for the taste of humans. We aren’t fish, and that’s what they want to eat. They’re incredible creatures.”

There are also more dangerous scenes in the film involving a tiger shark in which the actors were working with the real thing. The sharks used in the film were wild and could not be trained, so the shark used onscreen was one that was found at that day’s location. To ensure tiger sharks showed up when needed, Cove veteran shark wrangler, Alex Edlin, assembled a tiger shark hunting team that would get up at dawn to check the lines for any large shark that may have been trapped overnight. The team would then lift it into a box on their boat and transfer it to a special shark pen. (All the sharks were later set free).

However, the first large tiger shark caught had other ideas, according to Cove. “One morning we found that we had a 10-footer and we got all excited,” he says.

“It was splashing all over and as we tried to pull it into the boat, it got its teeth around a steel cable, biting right through it. It was devastating since we’d been up all night trying to catch him. It took another few weeks before we got another one that size.”

For Stockwell, using real sharks enhanced the feeling of realism he was seeking. “We got some incredible footage with all the actors and the sharks,” he says. “I want people to understand that these sharks are real. I think the film benefits from the fact that we didn’t rely on digitalized animation.”

To support the mammoth production above and below the water, an armada of boats had to be secured and kept at the ready throughout the shooting. Marine coordinator Ricou Browning (Bad Boys 2) collected more than 50 vessels, ranging from a 145-foot barge to a fleet of small inflatable Zodiacs. The main shooting vessel was a camera barge that Browning built and designed to meet the need of Into the Blue’s director of photography, Shane Hurlbut (Mr. 3000, Crazy/Beautiful). The shooting barge, named the Corinthian, carried a versatile long-armed crane that was used for shots in and on the surface of the water as well as for shooting scenes on the other boats.

Some of the other crafts used in the film ranged from the yachts Uniesse (Bryce’s rented pleasure boat) and the luxurious Milk and Honey (which is owned by the film’s kingpin) to the Sea Robin, Derek Bates’ functional treasure hunting boat rigged with a pair of “mailboxes” (rear-mounted funnels designed to blast sand from the ocean bottom).

The cast and crew were ferried back and forth between the set and shore by a swarm of smaller boats, with a large catamaran, Caribbean Queen, serving as the production’s floating cafeteria. Yet another vessel was used as a staging area for the actors, which included a hot tub for them to warm up in after having spent hours in the cool water. If there had not been a place for them to elevate their body temperatures, the actors wouldn’t have been able to work more than a few hours at a time.

A 145-foot barge was used for the delicate task of sinking two of the DC3 airplanes used in the film down to the ocean floor. Production designer Maia Javan (House of Sand and Fog) and art director David Klassen (Waterworld) decided not only what the planes would look like underwater, but chose the most photogenic sites for underwater director of photography Peter Zuccarini (Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl).

The production utilized three identical cargo planes for their needs. The “Sunshine” came from California, the “Jose” was found in Puerto Rico, and the “Kalik” was discovered right in Nassau standing at the entrance to the island’s airport. One plane was lowered into a deep-water site at the edge of a reef for use in longer establishing shots. Another was placed at a shallow water site for closer work. The third was dropped into a huge converted molasses tank and used extensively for close-ups and interior shots.

“The exteriors of the ocean planes were of special concern to us because of the wear and tear they would have to endure sitting on the ocean floor for an extended period of time,” explains Javan. “Just finding a calm day on which to sink the planes was a challenge. Once we found a flat ocean surface, we loaded the plane onto the barge and hurried out to our location. We lowered the DC3 very slowly on a giant crane until it filled with water. Then, we inflated buoyancy devices on a truss structure and lowered the aircraft with chain loaders and attached it firmly to the ocean floor with enormous moorings. It took more than 70 people to complete each dive.”

Of even greater concern was what undersea locations were suitable for the airplanes. Each site had to be cleared with the Bahamian Ministry of Tourism as well as with local environmental groups to insure that no reef or sea life would be adversely affected. “We placed a prefabricated steel structure covered with artificial coral as an anchor for both planes,” explains Klassen. “That way, we could secure the plane as well as give Peter Zuccarini interesting shooting angles that made the wreck look like it was in a precarious spot.”

Zuccarini, the veteran cameraman who as second unit director — underwater unit — worked closely with Stockwell to create some masterful underwater images that still adhered to strict safety guidelines. The unpredictable elements that scare most productions off the water were explored as unique visual opportunities for Into the Blue, according to Zuccarini. “John saw sharks, waves, seasickness, engine trouble, and doldrums as elements to be considered and worked into the story and the schedule.”

Zuccarini says he was thrilled that so much of Into the Blue was filmed in the actual ocean, since most productions shy away from working in the ocean because of the lack of control over conditions: Weather, light, visibility, temperature, etc. Our crew thrived in this environment. The underwater unit was a group of water junkies and shark fanatics, including the inventor of the chainmail shark suit, world renowned underwater cave explorers, world champion breath holders, Olympic caliber swimmers, shark diving specialists, dive rescue paramedics and an ichthyologist, to name just a few.”

While performing underwater the actors wore bikinis and boardshorts with minimal scuba gear. “We felt it was important for the cast to stay streamlined so they could move well in the action sequences while remaining recognizable,” says Zuccarini. “And their sun-bronzed bodies looked fantastic against the intensely blue Bahamian water.”

According to Zuccarini, Stockwell wanted to be able to follow the action above, below, and on the surface of the water as the actors moved in and out of the sea. Special lenses were designed to shed water drops and correct for refractive distortion to help the camera move in and out of the water continuously. “On the big screen this effect can be a beautiful transition from above water to the world of bubbles, no gravity and shimmering blue light,” says Zuccarini, “or it can feel terrifying when a character is trapped with water rising up on his face and the audience’s at the same time.”

Three-dimensional camera moves were employed without the laborious set-up time normally required to execute a dolly move or crane shot. Underwater, the camera was weightless, allowing the cameramen to get coverage from many angles and efficiently execute dynamic moves. The camera could follow an actor down an eerie tunnel, burst through a school of fish, reveal an unseen face and continue pushing in for a close-up on the eyes as the actor reacts inside his dive mask.

For the film’s nighttime salvage scene, powerful lights were mounted under the picture boat and the divers each had custom flashlights mounted on their scuba gear. “Ocean swells increased while we were underwater causing the light array to flop around in the huge waves,” Zuccarini explains. “On the sea floor the bright lights were sweeping around leading us in and out of total darkness. The effect was fantastic and increased the jeopardy for the characters as they salvaged the wreck not knowing who or what lurked in the darkness. To take the audience to the spookiest places inside the wreck we let the set go inky black except for the reflections created by the divers’ small flashlights.”

Into the Blue (2005)

Directed by: John Stockwell

Starring: Paul Walker, Jessica Alba, Scott Caan, Ashley Scott, Josh Brolin, James Frain, Dwayne Adway, Javon Frazer, Chris Taloa, Clifford McIntosh, Gill Montie

Screenplay by: Matt Johnson

Production Design by: Maia Javan

Cinematography by: Shane Hurlbut

Film Editing by: Nicolas De Toth, Dennis Virkler

Costume Design by: Leesa Evans

Set Decoration by: Les Boothe

Art Direction by: David F. Klassen

Music by: Paul Haslinger

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for intense sequences of action violence, drug material, sexual content, language.

Distributed by: Columbia Pictures

Release Date: September 30, 2005

Views: 266