Tagline: Every man fights his own war.

Jarhead movie storyline. “Like most good and great Marines, I hated the Corps. I hated being a Marine because more than all of the things in the world I wanted to be-smart, famous, sexy, oversexed, drunk, f***ed, high, alone, famous, smart, known, understood, loved, forgiven, oversexed, drunk, high, smart, sexy-more than all of these, I was a Marine. A jarhead.” Anthony Swofford, Jarhead.

In the summer of 1990, Anthony Swofford, a 20-year-old third-generation enlistee, got sent to the deserts of Saudi Arabia to fight in the first Gulf War.

In 2003, his memories of that time in that place became the best-selling book Jarhead. Swofford wrote with the urgency, immediacy, honesty and humor that could only come from someone who had lived through the experience itself.

Swofford’s book spent nine weeks on The New York Times list of best sellers and was hailed in that same publication as “some kind of classic…a bracing memoir of the 1991 Persian Gulf War that will go down with the best books ever written about military life. A wild passage familiar to millions of young men but rarely so well revealed.”

The Times’ Michiko Kakutani noted that Jarhead was “an irreverent but meditative voice that captures both the juiced-up machismo of jarhead culture and the existential loneliness of combat. He makes us understand the exacting and deadly art practiced by a sniper…the rhythm of boredom and terror of preparing for an enemy attack and the terrible physical and psychological costs of combat and the emotional bonds shared by the soldiers.”

Here was the unvarnished story straight from the mouth of the then 20-year-old kid, who told of a very different war from the one delivered in print or over the air. Here was the war from the ground up with images of burning oil wells shooting flames into the night sky, like comets that had fallen to the earth; rowdy, horny, dusty recruits, exhilarated and also terrified that at any moment, over the next hill, the war might begin; young men, suddenly dropped down in an unforgiving terrain, seeking diversion in a game of gas mask football, awaiting care packages of letters and porn, betting on staged scorpion fights and getting blind drunk to celebrate a Christmas away from their families. But out of this hellish situation ultimately arose unlikely friendships, fierce loyalty and do-or-die camaraderie-a brotherhood of jarheads sworn to be always faithful…semper fi.

Mendes and the filmmaking team now collaborate on the next generation of war movies with Jarhead, an unforgettable view of war as seen through the eyes of one Marine-as if J.D. Salinger’s Holden Caulfield had been deployed to the Gulf.

Recruiting the Filmmakers

“When I first read the book, what I responded to was the fact that the war was viewed through the prism of a very specific kind of person: one who was trying to deal with and discover who he was. I was enthralled by the mixture of machismo, comedy, surrealism and wry observation,” director Sam Mendes recalls about first reading the Gulf War memoir Jarhead. “It was a war book like no other, about a war like no other, that might possibly be a war movie like no other.

“Every Marine has a different experience, every platoon has a different experience, every battalion has a different experience-even of the same war. I was interested in making a movie about this particular fascinating individual and how his experiences in this war shaped him.

“What we remember about the Gulf War,” continues Mendes, “were these clean little images of these tiny little bombs perfectly hitting these toy towns, bereft of any sense of human life at all. A soldier on the ground has absolutely no idea of what’s going on. To me, the interesting thing now is to enter it through a person on the ground, because that’s where we weren’t allowed to go in this particular war. Tony’s experience in the desert took what we consider normal about war, on its head-as if Salinger were dealing with the Gulf War.”

Swofford’s best-selling and critically acclaimed book about life as a Marine in the early 1990s had been praised for many things, notably the painful honesty and irreverence with which the narrator viewed his world-a first-person observation from a third-generation soldier (Swofford was conceived in 1969 when his father was on leave from Vietnam) of the war machinery that surrounded him. In place of the classic imagery of scrubbed, uniformed heroes dedicated to a cause were young recruits in sweaty desert gear with a passion for rock music, a predilection for pornography and a growing and unfulfilled bloodlust.

Having been trained for the kill and then stationed in a barren, inhospitable, surreal landscape, the testosterone-charged crucible produced alpha-male infighting (since there was no enemy in sight), debauched behavior and general disrespect for everyone from their commanding officers to the people they were sent to liberate… and all of it narrated by a soldier who is, at first, more at home reading Camus than adjusting to the harsh realities of jarhead life.

“If I was going to tell any story about the Gulf War, the one that I needed to tell was my own,” says Swofford. “I was 18-years-old when I joined the Marine Corps in December of 1988. The Marine Corps itself is very seductive for certain young men. Once I was in the infantry, I saw a group of guys who carried better rifles and had better gear. I found out they were the snipers, and there was a mystique about them.”

Swofford was then given the opportunity to advance from being a “grunt” to becoming a scout/sniper in the elite STA (Surveillance and Target Acquisition) Platoon. “The grunt fights for 15,000 poorly placed rounds; the sniper dies for that one perfect shot-I was hooked.”

Producing partners Lucy Fisher and Doug Wick, who purchased the book just as it was hitting the streets, believed in the timelessness of the material and the singularity of the author’s painful, funny and observant voice. Their faith was confirmed by screenwriter William Broyles’ own experiences as a Marine in Vietnam.

With a son in the military, Broyles identified with Swofford’s story, as both a father to a young soldier and someone who’d seen combat first-hand. He says, “Tony’s generation had a more clear sense of purpose. For whatever reason, they all wanted to be there. We were drafted. And by the time I got there in 1969, we had no idea what we were there for.”

“When I first spoke with Bill about adapting the book, he started explaining to me, from his own experiences of serving in Vietnam, that it’s a club you never leave,” says producer Doug Wick. “I was kind of surprised to hear this sophisticated writer-whose time in the service was nearly four decades ago-talk about how he was a Marine forever, how those guys who knew each other so briefly, so long ago, felt linked forever. It struck me that this was a story worth telling.”

Broyles adds, “When I got back from Vietnam, I missed having my weapon. There’s some kind of primal connection you have with your rifle-it’s like a cowboy and his horse. You take the cowboy off his horse and he still walks bowlegged because they are one thing, just like you and your rifle.”

As told by Swofford and echoed by Broyles, soldiers in wartime experience something outside of the realm of understanding of most civilians-that adrenalized high that comes from the relentless intensity of everything the soldier does, from the seeming monotony of training and drills to the actual time in battle. For them, the viewing of such now classic films as Apocalypse Now, Platoon and Full Metal Jacket works as an aphrodisiac, whetting their appetites for the coming conflict and celebrating the beauty of their fighting skills. These themes, combined with Swoff’s own unique story of growing up in this hothouse environment, would make a screen adaptation a tricky feat to pull off.

Lucy Fisher comments, “The book is unique in both style and content, and we knew it would require some extraordinary talents to make it cinematic. It’s a very literary work, a coming-of-age story in the midst of chaos that’s alternately funny and terrifying. Once Bill had a first draft screenplay, we set our sights on the one director we believed had the vision to put it all together: Sam Mendes. We wanted somebody with the intelligence to deal with the actual seriousness of the topic and yet know how to make it funny-Sam does that brilliantly.”

Wick adds, “American Beauty was `Sam Mendes Goes to the Suburbs.’ Jarhead, which has some of that same sensibility, is a little bit `American Beauty Goes to War.’”

Fisher picks up, “Sam is such as stylist and such a humanist that the fact we saw so little of the human side of this war was a unique creative opportunity for him. What was unusual from the public’s perspective is that so few images from this war were ever shown on television, in newspapers or in magazines. So, this movie will contain imagery that you will never have seen in any other way.”

“I think you need time, you need hindsight, to begin to understand what you have lived through, particularly if you’re going through something as seismic as a war,” observes Mendes. “As often happens with huge historical events, you need a bit of distance to fully understand them. The Gulf War is certainly a different event now from what it appeared to be then.”

As viewed through the lens of mass media at the time, Operation Desert Storm seemed like the perfect war-if one can apply such an oxymoron. And as such, it proved to be a brand new experience, even for the most seasoned soldier.

Mendes offers, “It’s fascinating to me that it took ten or twelve years before a lot of the guys wrote memoirs about this first Gulf War. You’ve got to ask yourself, `Why were there so few in the immediate aftermath of the war? Why did it take this much time?’ And I think the answer is that what seemed to them at the time almost a non-war now, in retrospective, seems much more interesting. I think we realize now what it was part of, historically speaking. The intensity of that experience has a huge amount to tell us about what’s going on now.”

Mendes and Broyles worked on many drafts of the script, pulling Swofford’s story out of the non-linear episodes chronicled in the memoir and concentrating on his time while in training and in the desert. (Swofford was deployed on August 14, 1990, just two days after his twentieth birthday. His battalion, the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Marines, was one of the first units to reach the Gulf and was instantly dispersed into the desert. They immediately dug in and waited for the fighting to begin…)

Mendes explains, “Immediately after a war is finished you get the factual accounts, the details. What we’ve tried to do is take the feelings, the impressions, the subjective version of events to create a different account of this war.”

Broyles adds, “Our story is unromantic and apolitical. It’s about young men who join the Marine Corps trying to find a place for themselves in life.”

Enlisting the Platoon

“I’d read the book on a plane and came away really moved by it-it was purely emotional and without any of the clichés of other war stories,” says Jake Gyllenhaal. “When I got the script, I was told by Sam [Mendes] that Bill [the screenwriter] had served in Vietnam and, to be honest, I had some concerns about that.

“To me, Vietnam was a different generation, a war that everyone of that generation was involved with in one way or another. I was 11 when the Gulf War started. There is a kind of weird distance from it. We don’t have the same experience of it that the Vietnam generation had of that war.”

Gyllenhaal’s concerns were alleviated once he read Broyles’ adaptation of Swofford’s memoir. He was instantly eager to take on the challenge of portraying the author-but found he would have to wait a bit.

After his first reading for Mendes, Gyllenhaal got the ominous feeling that he didn’t nail the audition. After a few months had passed and the actor heard that the director was meeting with other actors, Jake left an impassioned message on Mendes’ voicemail (“I’ll do whatever you want me to do, but I’m the guy to be in this movie!”). A month later, the director informed him he had the part.

In addition to downplaying his chances of securing the role, Gyllenhaal underestimated the physical-and mental-transformation the role would bring about.

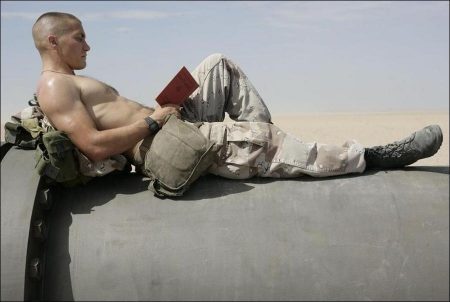

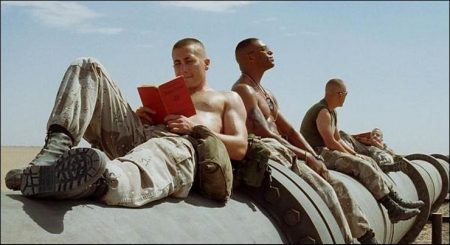

“When the other guys and I first got our jarhead haircuts, I was really into it-and then, as soon as it happened, it was odd to me,” Gyllenhaal recalls. “But I think that feeling was appropriate. I think that Swoff likes to stay apart from the group. He’s an observer as well as a team player, and Sam created an atmosphere in which I could observe and be a part of a group simultaneously. I always felt an interesting juxtaposition of feeling like I was an integral part of the platoon while simultaneously feeling apart from it. I think that was Sam’s intention.”

Peter Sarsgaard-who plays Troy, Swoff’s friend and spotter / partner in the STA-offers, “The main reason I wanted to do this film was because I felt like it acknowledged the hardships of what it means to be in a war. We just got a little touch of it through being in this movie. I mean, in the end, we’re just actors.

“What was the most difficult for us were the elements, mostly. We were either freezing our asses off-being soaked in the rain for 12 hours or out at night in the desert-or we were frying-working in the sun in full combat gear or making our way through a sandstorm. But it’s a little obnoxious to complain about things like that when there were guys over there who did just that for months and had to face live ammo.”

Another aspect of military life for the first Gulf War soldiers-and all soldiers who served prior to the gender integration of the armed forces-that presented a period of adjustment for new actor/enlistees was the absence of women in their midst.

“I’ve gone through real bonding experiences working with groups of actors, but there’s something about being around a large group that’s almost exclusively male that’s totally unique,” Sarsgaard explains. “I mean, there’s the script supervisor and a camera loader, and maybe only one or two other women on the crew. Even the hair and makeup people were nearly all men.

“Frankly, I think we all got sick of it,” he laughs. “Male banter gets really raunchy, and you get a little tired of it. There’s something about the banter that’s tied in with the violence, and it’s usually always centered around sex. Sex and violence-there you have it. Factions form, too. I think of all the movie sets I’ve been on, this one has had more bickering-and more love-than any other.”

Staying appropriately out of the grunt grappling was platoon leader Jamie Foxx.

“I think it’s very appropriate that Jamie Foxx plays our staff sergeant,” says Gyllenhaal. “Everyone respects him as an actor. He keeps himself apart from the guys, quietly playing chess between scenes. We all play him, and he always wins. There’s a pecking order in the Marine Corps just like there is on a movie set. And it’s just so easy to look to Jamie as our leader. I instinctively and naturally look up to him.”

Foxx comments, “One of the first things Sam told us was, `Read the book, but don’t take it to heart, because the movie is going to be something different.’ The book was just one man’s thinking of how he was affected by the war. The movie lets you see everybody’s side of the thing. My side is with the Marines.”

Prior to filming, Foxx also spoke with a friend who happens to be a Marine: “He’s African American, so he’s always had to work harder and be sharper. But he said once you become a Marine, that’s your family. There’s no color except the color of your uniform. You’d never survive without the camaraderie.”

Another Academy Award winner, Chris Cooper, was charged with bringing the zealous, smart and charismatic Lieutenant Colonel Kazinski to life. Kazinski wields his leadership skills like a sideshow barker or Vegas M.C.-he is a motivator who knows how to whip up a crowd. But beneath the huckstering is a shrewd soldier with battle scars and medals to back up his rank.

“In a life-threatening situation, a group of young men are looking toward someone for leadership. They can tell when they’re being fed a line,” shares Cooper. “Kazinski is a motivator who gets how to energize a crowd, and he understands that a good commanding officer must wear many different hats. He knows when it’s time to be a best friend, when to be a father figure and when to drive his men into the ground. Because this soldier is responsible for the lives of his troops, he believes he must have the smarts and the skills to back up his zeal. It was this dynamic that made Kazinski an interesting character to me.”

Foxx’s Staff Sergeant Sykes represents the lifer, the type of soldier whose unshakeable belief in the Corps way of life is all consuming-the compass by which he steers his course; Cooper’s Kazinski, the same. For the Marines under their command, however, life has many more shades of gray than the black and white way of life lived by their leaders. For them, the party line is a lot harder to swallow.

Lucas Black plays Chris Kruger, company rebel, who seems to be one of the only ones in the troop with any concern of the politics that got them into the war.

“My character likes to joke around, and he tries to get on some people’s nerves by asking a lot of questions,” says Black. “He knows a lot about what’s going on, and he likes to put questions in people’s minds-why are we here and what are we doing here?” Kruger’s questioning nature is made evident in a scene where the platoon is issued additional pills to protect them from potential chemical and biological weapon attacks-issued as back-up to their NBC (nuclear / biological / chemical weapons) suits. After ascertaining that the military has yet to test the experimental drugs, Kruger is the only one in his unit who does not swallow the meds.

The other soldiers in Swofford’s unit run the gamut from rebel to rank-and-file: Evan Jones, as the loudmouthed, cocky Fowler; the shy social misfit Fergus O’Donnell, played by Brian Geraghty; Jacob Vargas’ committed fighter Cortez; and the imposing Cuban American Escobar, played by Laz Alonso.

It was Mendes’ intention that all the actors experience as much of Marine life as possible. With the reality of time constraints and filming schedule, however, the director knew that the best he could hope for was a somewhat superficial transmutation. Yet he was determined to at least give the actors a taste of the “real thing.”

Prior to the start of principal photography (which itself was preceded by a thorough three-week rehearsal), the platoon of 13 actors/soldiers attended a four-day boot camp at George Air Force Base, led by military advisor Sergeant Major James Dever (who has assisted large-scale filmed military operations in projects such as The Last Samurai and We Were Soldiers).

“We lived in tents-the exact kind of tents that they would be using in their camps out in the desert-and we slept on cots,” Dever explains. “And we made sure the training they received was the same as what the Marines receive before going to the desert. It was basic Marine Corps training, albeit sped up. The actors were very motivated.

“We issued equipment to them the first day. We showed them how to put on their combat gear, where to put the canteens, the magazine pouches, things like that so they would understand the equipment. No walking-they had to run everywhere. We went on forced marches carrying full packs. Every morning we went through physical exercises and drills. We gave classes at night on the NBC suits and protective masks. They worked hard, but there was no complaining. And everything was very quick.”

“I wanted them to have some idea of what it felt like,” says Mendes. “But it was nothing compared to what Marines go through. I’m one of those people who gets bored of hearing actors say, `We went to boot camp, and we know what it feels like to be Marines.’ They have no idea what it feels like to be Marines, and neither do I. What I wanted them to have was a physical knowledge of certain things so they could accurately portray Marines.

“Did I push them physically beyond the point that I normally would with an actor?” he continues. “Yes, absolutely, because they’re acting physically. They’re experiencing the pain, the exhaustion, the heat. I wasn’t going to push them to the point where I had collapsed actors on my hands, but I wanted them to go a little further than they would go normally.”

Mendes notes that the combination of the subject matter, the setting, the testosterone and commitment made for an intense experience for everyone involved: “I feel like there’s something that went on between all the actors in this production that they’ll carry with them back into their private lives. I think they were affected deeply by the depersonalizing influence of being in the military. I think there’s a certain type of human being that seeks that-to be part of a team, to be part of something bigger than themselves, to lose themselves in something with a grand objective.

“But I think you’ll find that they are opposite to the types who want to be an actor,” he continues. “I think the friction between those two has led to a lot of what has gone on on-set. It’s made each performance a struggle for individuality within the context of a group. I wanted to take the actors by surprise-I wanted it to be a journey of discovery for them. Coming from the theatre, the process, the journey is its own end result. And I think here, this journey has been a fascinating experiment-for all of us.”

Mendes concludes, “I think it’s very difficult for most human beings to sublimate where they stand in the world, put that on hold and just be a body-because at the end of the day, that’s all you are when you’re in a war situation. There’s a reason why everyone looks the same, because fundamentally, they are the same. You have to be well trained to spot any insignia anywhere on a Marine uniform: no names, nothing. Everyone looks the same. It’s deep in the psychology of the Marine Corps. It’s beyond my comprehension on some level. But it’s also something I hugely admire and respect because it’s very, very selfless.”

Jarhead (2005)

Directed by: Sam Mendes

Starring: Jake Gyllenhaal, Jamie Foxx, Peter Sarsgaard, Lucas Black, Chris Cooper, Katherine Randolph, Brian Geraghty, Dendrie Taylor, Rini Bell, James Morrison, Becky Boxer

Screenplay: William Broyles, Jr.

Production Design by: Dennis Gassner

Cinematography by: Roger Deakins

Film Editing by: Walter Murch

Costume Design by: Albert Wolsky

Set Decoration by: Nancy Haigh

Art Direction by: Stefan Dechant, Marco Niro, Christina Ann Wilson

Music by: Thomas Newman

MPAA Rating: R for pervasive language, some violent images and strong sexual content.

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Release Date: November 4 2005

Views: 193