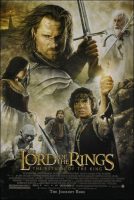

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King is a 2003 New Zealand-American epic high fantasy adventure film produced, written and directed by Peter Jackson based on the second and third volumes of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. It is the third and final installment in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, following The Fellowship of the Ring (2001) and The Two Towers (2002), preceding The Hobbit film trilogy (2012–14).

Released on 17 December 2003, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King received widespread acclaim[9] and became one of the most critically and commercially successful films of all time. It was the second film to gross $1 billion worldwide ($1.12 billion), becoming the highest-grossing film released by New Line Cinema, as well as the biggest financial success for Time Warner in general at the time. The film was the highest-grossing film of 2003 and, by the end of its theatrical run, the second highest-grossing film in history. As of May 2017, it is the sixteenth highest-grossing film of all time.

At the 76th Academy Awards, it won all 11 Academy Awards for which it was nominated, therefore holding the record for highest Oscar sweep. The wins included the awards for Best Picture, the first and only time a fantasy film has done so; it was also the second sequel to win a Best Picture Oscar (following The Godfather Part II) and Best Director. The film jointly holds the record for the largest number of Academy Awards won with Ben-Hur (1959) and Titanic (1997). The film has been re-released twice, in 2011 and 2017.

Loyalty, Destiny and Hope

“You have a massive war on an external level, and on an internal level you have two little Hobbits, Frodo and Sam, on their hands and knees literally crawling up a mountain. The relationship between those two characters is the heart of the movie.”

— Peter Jackson.

More than any other installment in The Lord of the Rings saga, The Return of the King illuminates the enduring themes at the heart of J.R.R. Tolkien’s novel. All of the storylines we have followed, the journeys that these characters are taking — what they care about, what they’ve been fighting for, even what some of their friends have died for — lead to this film,” comments Peter Jackson. “None of these characters is going to come out of this story unchanged. They’ll never be the same again. The Return of the King is the most emotional of the three films.”

Though the stage is vast in scale, the true heart of The Return of the King is in the dramatic struggles of each character introduced in the epic trilogy. “There is an emotional resolution to each and every character whom we’ve grown to know and love throughout the telling of these stories,” comments producer Barrie M. Osborne. “Will they succeed or will it end in tragedy? I think it will bring people to tears and joy both.”

The Reluctant King

The title, The Return of the King, refers to Aragorn, played by Viggo Mortensen. The heir to the Kingdom of Gondor, Aragorn has hidden from his heritage, living out his life instead disguised as Strider, one of the mysterious Rangers – wanderers who perform discreet military operations against Sauron. Yet the throne of Gondor is empty. The Kingdom is in decline. As Sauron threatens to eradicate all the races of Middle-earth, the moment has come for him to step forward and face his urgent destiny to lead. “How do you assume the mantle of a king?” Jackson asks. “How do you take that on yourself? How do you say `I am the one that you must follow’? I think that is what he’s struggling with, because he has seen what power can do.”

Ambivalent about his lineage and the ancestors who fell in disgrace through their quest for power, Aragorn struggles with personal doubts that he is truly the one. “He is the heir to the throne; he is the sole person capable of assuming this position in Minas Tirith, but he is unsure of his worthiness to lead mankind,” comments Jackson. “Aragorn needs to believe in the nobility of his own people.”

Mortensen identifies Aragorn with the image of the prodigal leader whose true nature is initially hidden, “from his companions and, for a while, from the world at large,” he explains. “A person such as Aragorn, much like King Arthur or Moses, for example, is raised by non-blood relatives, hidden until he is ready to learn of his true identity and the great responsibility that is his birthright. Aragorn, who was brought up by the Elves in Rivendell and tutored by Elrond, must eventually fulfill a destiny that requires him to understand the complex and tragic history of Middle-earth, and to ensure a future born of hope and justice for all beings of that world.”

Yet to Aragorn, the throne represents the very quest for power that tempted and ultimately destroyed his ancestors. Power would alter everything that makes him who he is. What Aragorn finds in his journey is that the call to lead is not for power at all. “What’s at stake is a city which is falling to an enemy,” explains co-screenwriter Philippa Boyens. “Many people will die as a result. Aragorn decides that if it is in him, and it is going to save people’s lives, he will do it. He steps up to the mark. His motives are pure, which is one of the reasons he’s not corrupted by The Ring. Because it’s not power for power’s sake.”

With Sauron’s forces also comes recognition that death is encroaching with the irrevocable passage of time. Aragorn’s journey requires a confrontation with the very souls that betrayed his ancestors in the treacherous Paths of the Dead. It’s a road from which he may not return, yet he enters it without hesitation to stave off not only mass death but the intractable destruction of those he loves. “For me, the story is about confrontation with death, about the consequences of death for us and for those we love,” Mortensen reflects. “That’s a significant reason why the story continues to resonate with modern audiences.”

Gandalf (Ian McKellen), who sets The Fellowship’s quest in motion – and sends Frodo into Mordor – must confront the repercussions of his own role in the quest. No longer a benevolent outsider, Gandalf, too, actively joins the fight on the side he believes must triumph. “In a way, Gandalf is a general in this war,” comments Boyens. “He initiated this and caused it to happen, and he must bear the responsibility for that. It was an awesome gamble. That is power wielded in another way and it bears a different, but equally profound cost.”

The Ubiquity of Good and Evil

Frodo is The Ringbearer, the one who has been entrusted with the pivotal quest — to carry The Ring to Mount Doom, the only place where it can be unmade. Yet The Ring around Frodo’s neck becomes heavier with each step, eroding him the longer he wears it until nearly robbing him of his very essence. “Essentially, you see his complete deterioration to the point that Frodo ceases to be Frodo anymore,” comments Elijah Wood.

Yet his proximity to Gollum reveals not only what The Ring has done, but what it will do to him. “Frodo has a true understanding now of what The Ring is,” says Boyens. “He understands the nature of what it is that he carries, and that it will try to destroy him. The Ring’s weapons are things like despair. But he also has this understanding from Sam that they have to keep going forward, no matter what. They have no choice but to persevere.”

The most enlightened beings in Middle-earth – such as Gandalf and Galadriel – are conscious of the ubiquity of good and evil – in neighbors, strangers, adversaries, and, most importantly, themselves. They are reluctant to even touch The Ring. The totem and its connection to power warped Gollum and is working its influence on Frodo. “Gollum is the dark side of humanity,” says Andy Serkis, who portrays him in the films. “But I tried to look at him in a nonjudgmental way – not as a sniveling, evil wretch, but from the point of view of, `There but for the grace of God go I.’ We can choose to demonize anyone with uncontrollable obsessions, but if we don’t seek to understand them, then we can never hope to grow as human beings.”

Frodo’s constant companion throughout the quest is Sam. “Frodo and Sam are affected in different ways, and yet the two of them have to be together to see this through,” comments Jackson. “Frodo is The Ringbearer. He is the only one that can carry this Ring, yet every footstep that he takes closer to Mordor, closer to Mount Doom, becomes harder and harder for him.”

Sam never abandons Frodo, even as The Ring drives a rift between them. The presence of his old friend presents an alternate reminder of his home in Hobbiton, and what he was before The Ring came into his life. Putting their friendship and Frodo’s well being above even his own life, Sam’s loyalty and determination alter the balance of power in subtle but powerful ways. “There’s a wonderful line that Tolkien wrote about Sam and it is, `His will was set and only death would break it,’” comments Jackson. ”I think we’ve moved most of our characters to that point.”

Unlikely Heroes

Éowyn (Miranda Otto) and Merry (Dominic Monaghan) are left behind at the Rohan outpost of Dunharrow – Éowyn, because she is female, and Merry, because he is a Hobbit. “Éowyn is very dissatisfied with her role as a female in the land of Rohan,” comments Jackson. “She has a warrior spirit. She wants to defend her people. She wants to defend her uncle, who is the king, about whom she is fiercely passionate. So, we see her in a rather devious way sneak off to battle; and, of course, she must confront the true horrors of battle once she’s in the thick of it.”

Éowyn’s kindred spirit and companion into battle is Merry, who is likewise transformed by this war. “To see war from his eyes is just horrific,” comments Monaghan. “To see Merry in that situation, covered in blood, sweat and tears, and living the terrible reality of war is really traumatic. But in Merry’s heart he has every bit as much of a right to be there as anyone else. He’s fighting for the same things they are – to save his friends and to save his world.”

At a crucial moment in the battle, their unexpected courage and fierce loyalty help turn the tide against their enemies.

Fathers and Sons

“In film three, a huge part is the conflict between fathers and sons,” comments Boyens. “Just as Gollum’s schizophrenia is buried in the story and you have to dig it out, you have this story of fathers and sons.”

In The Lord of the Rings, the actions of every father come back to rest at the feet of his son. Likewise, sons or daughters are often put into direct opposition with their parental figures. Éowyn’s surrogate father, Théoden, forbids her from going to war. Yet she ultimately plays a critical role in his army. And Théoden himself is haunted by his own son’s death while Théoden was under Wormtongue’s poisonous influence.

In his love for Arwen and desire for her to stay with him, Aragorn is in direct opposition to the will of his surrogate father, Elrond, who raised him. This conflict comes to bear in Aragorn’s fated decision to ride to the Paths of the Dead, for it is Elrond who must reforge the Sword of Kings (Narsil) and essentially give Aragorn his blessing to use it. And Gandalf, who is very plainly a father figure to entire Fellowship, sends his vulnerable “son,” Frodo, on the most brutal and unforgiving mission — to destroy The Ring in Mount Doom — yet cannot come to his side when Frodo direly needs him.

But perhaps the most prominent and heart-wrenching relationship is that of Denethor (John Noble) and his sons, Boromir (Sean Bean) and Faramir (David Wenham).

Denethor, who is charged with watching over Gondor in absence of its King, is despondent over the death of his favorite son, Boromir, and believes that Faramir, his only surviving son, has failed him by not taking The Ring for Gondor when he had the chance. “Boromir was Denethor’s favorite in the sense that he was a mirror of his father,” says Noble. “He was a strong warrior and a born leader; whereas Faramir was more introspective and academic perhaps in the image of Gandalf. The death of Boromir was unbearable for Denethor. It was as if he’d been killed himself.”

In guilt or perhaps madness, Denethor sends Faramir into a fight he can’t win – to lead troops into battle against the Orcs in the fallen city of Osgiliath. And Faramir willingly goes. “Faramir is very straightforward and not political at all,” comments Wenham. “His father distrusts him, in a way. He has put Faramir in the excruciating position of doing something that doesn’t come naturally to him. He’s being forced to lead an enormous group of men into very difficult and harsh circumstances. Yet Faramir loves and trusts his father, and essentially rides to his death in obeisance to win his father’s approval. He realizes there’s no hope in going back into Osgiliath, but he would gladly give his life for the future of Gondor, and for Middle-earth.”

“It’s a waste, a foolish act,” comments Boyens. “Yet the act itself is enormously heroic. It is being driven by pain and suffering of this young soldier who is trying to gain a father’s love. Gandalf says to him, `Your father does love you, and he’s going to remember it before the end. So don’t throw your life away.’ Within the context of war, futility often springs from very personal causes that people play out with other people’s lives.”

The Fellowship of Humanity – Acceptance and Tolerance

The two kingdoms of Rohan and Gondor have spent a lifetime in uneasy co-existence. Yet as both fall under siege, combining their resources and power becomes their only option for survival. As Rohan and Gondor ultimately join together against their common, and overwhelming, enemy, so does an unlikely trust spring out of the hardships experienced by Gimli (John Rhys-Davies), a Dwarf, and Legolas (Orlando Bloom), an Elf.

Though they set out on the quest in opposition, as they rely increasingly on each other for both survival and companionship, they form a bond that transcends race and prejudice. “At our best, we, like the Fellowship, realize individually and collectively that peaceful co-existence can be achieved only through vigilance and conscious compassion,” says Viggo Mortensen. “Compassion for oneself and others, especially for those determined to do us harm. An effort to identify with others leads to an understanding that there is no absolute difference between us.”

“To me, the characters in this film exemplify the positive aspects of life,” reflects director of photography Andrew Lesnie. “It’s not necessarily promoting one particular ideology, religion or philosophy, but saying that you accept that there are differences in the world and you are prepared to embrace those differences. If enough people manage to approach the world in a positive, loving way, you may actually change the nature of the human race on a regular basis. And this story is an example of a group of people who triumph by following that aim.”

The Power of Hope and Unity

The presence of hope may level the playing field between Sauron’s massive forces and the coalition united against him. Yet even Gandalf recognizes that this monumental quest on the shoulders of a small Hobbit carries little more than a “fool’s hope” of success.

In times of war, a tremendous price is paid for every victory. But as long as hope lives, the chance for good to prevail will continue to exist. Though Aragorn grapples with his own confidence in the worthiness of mankind, Arwen (Liv Tyler) maintains unshakeable faith in the future of the world, sacrificing her own immortality to support Aragorn in his quest. “Tolkien was passionate about the goodness that can reside in men,” Boyens comments. “This notion is embodied perhaps most strongly in Arwen, who never gives up hope that mankind has a future.”

What drives the characters forward is not an urge to prove themselves worthy. They are interdependent, fighting, as Boyens explains, for each other. “Their faith is being put to the test,” she adds. “Their faith in each other, in good, in the ties that bind.”

In crafting the screenplay, writers Boyens, Jackson and Fran Walsh were constantly reminded of these universal touchstones to the human experience. “These are themes that are very close to what we live every day,” Boyens explains. “How do you feel about the people you love? What comes next after this life? How do you say goodbye? All of those emotional threads are very powerfully written by Professor Tolkien in the story. The eternal nature of the struggle of good versus evil is portrayed in little silver threads that run through the story, like Sam who, as Frodo sleeps, looks up into the thick industrial skies over Mordor and sees a star.”

“It is the humanity of the characters that rewards the reader,” says producer/co-writer Fran Walsh. “And we hope we’ve been able to translate that for the film audience.”

“These are extraordinary times that Gandalf and the rest are living through, and extraordinary demands are being made on people’s spirit,” Ian McKellen adds. “All the characters can be seen in that way whether they have magical powers or not. They are reflecting back on our experience of being human. For everyone is being measured. Can they survive? Can they live up to their responsibilities?”

A Timeless Story That Still Resonates

Though written a half-century ago, The Lord of the Rings remains relevant while history churns on. Many readers, particularly during times of darkness in the world, believe that Tolkien was commenting on wars and militaristic behavior in his mammoth book. “I can’t be the only one of my generation that was born in 1939 to think that here was some sort of parable of the real world politically and militarily that Tolkien was living in,” McKellen says. “Tolkien had himself served in the First World War and wrote The Lord of the Rings during the Second World War while his son was fighting in northern France. I don’t think there are any Saurons around today but in 1939, there was one. Sitting in the middle of Europe. A spider who wanted to control it, and the world joined together in a mighty coalition to defeat him.”

Christopher Lee, who plays Saruman, adds that men of genius, intellect and power who take the dark path – like Saruman — will always require their opposite to take them on. “Tolkien places Gandalf in opposition to Saruman – two sides of the same coin,” says the actor. “Here you have the universal conflict between good and evil, and the powers behind those two elements. That will have a relevance for every audience, everywhere, because we all know, or have heard of, such people and conflicts in our world.”

“I think The Lord of the Rings will live forever because it’s truthful,” adds executive producer Mark Ordesky. “And because the issues it deals with will be pertinent forever. It doesn’t matter what generation and what age is experiencing it. The story will always have something relevant to say to that audience.”

Over the centuries, clearly human archetypes appear and recur throughout Greek, Roman and Norse mythologies, from Eastern and Judeo-Christian ideologies to the works of William Shakespeare. The human truth contained in these experiences is what makes them universal, not the time or place. “Myth – just like religion – is dead unless you keep reinvigorating and reapplying it,” says Viggo Mortensen. “I think that what Tolkien did with some of the elements from the sagas and Celtic legends that I know and love was to forge something new, reinvent a lot of these archetypal stories and characters for his generation. Now, Peter Jackson is doing that for ours.”

Against the vast, sprawling canvas of war is an intensely human story. “It was about inner courage and about close friendships and about the possibility of wisdom somewhere in the world, by defeating the forces of stupidity and evil,” reflects McKellen. “I think the story goes on being relevant not necessarily because of its subject matter but simply because of the brilliance by which it is told, and Peter Jackson’s film is also the work of a brilliant storyteller. That’s why these films are as popular as the books have been and continue to be.”

“Like Tolkien, Peter is taking us on a journey that is as big as our own history,” adds Weta Workshop’s Richard Taylor. “It is an historical document to some degree. But in all history, there are intimate and heartbreaking stories. Love, hate, viciousness and jealousy fuel the world and ultimately create the history that has come from the writings of Tolkien. And Peter, in turn, has filmed these characters and these moments that give the story the intimacy that it so deserves.”

Each individual journey taken by the characters of The Return of the King, the losses they suffer, the sacrifices they make, continue to resonate in today’s world. “There is not an easy or permanent answer to the troubles of today or tomorrow,” says Mortensen. “A sword is a sword, nothing more. Hope, compassion and wisdom borne of experience are, for Middle-earth as for our world, the mightiest weapons at hand.”

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003)

Directed by: Peter Jackson

Starring: Elijah Wood, Orlando Bloom, Ian McKellen, Sean Astin, Viggo Mortensen, Christopher Lee, Liv Tyler, Cate Blanchett, David Aston, Bernard Hill, Alistair Browning

Screenplay by: Peter Jackson, Frances Walsh, Philippa Boyens

Production Design by: Grant Major

Cinematography by: Andrew Lesnie

Film Editing by: Jamie Selkirk

Costume Design by: Ngila Dickson, Richard Taylor

Set Decoration by: Dan Hennah, Alan Lee

Music by: Howard Shore

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for battle sequences, frightening images.

Distributed by New Line Cinema

Release Date: December 17, 2003

Views: 101