Tagline: His life changed history. His courage changed lives.

In 1977, Harvey Milk was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, becoming the first openly gay man to be voted into public office in America. His victory was not just a victory for gay rights; he forged coalitions across the political spectrum.

From senior citizens to union workers, Harvey Milk changed the very nature of what it means to be a fighter for human rights and became, before his untimely death in 1978, a hero for all Americans. Sean Penn stars as Harvey Milk under the direction of Gus Van Sant in Milk, filmed on location in San Francisco from an original screenplay by Dustin Lance Black, and produced by Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen.

Milk charts the last eight years of Harvey Milk’s life. While living in New York City, he turns 40. Looking for more purpose, Milk and his lover Scott Smith (James Franco) relocate to San Francisco, where they found a small business, Castro Camera, in the heart of a working-class neighborhood. With his beloved Castro neighborhood and beautiful city empowering him, Milk surprises Scott and himself by becoming an outspoken agent for change.

With vitalizing support from Scott and from new friends like young activist Cleve Jones (Emile Hirsch), Milk plunges headfirst into the choppy waters of politics. Bolstering his public profile with humor, Milk’s actions speak even louder than his gift-of-gab words. When Milk is elected supervisor for the newly zoned District 5, he tries to coordinate his efforts with those of another newly elected supervisor, Dan White (Josh Brolin). But as White and Milk’s political agendas increasingly diverge, their personal destinies tragically converge. Milk’s platform was and is one of hope – a hero’s legacy that resonates in the here and now.

Background: Milk / Castro

As a politician and activist, Harvey Milk was an aggressive populist. Milk believed in the service of government to meet the needs of all members of society. He encouraged gay men and women to come out of the closet, inspired different communities and unions to pool their resources, and rallied everyone against discriminatory legislation. Speaking not long before his murder about lobbying for gay rights, Milk said (in the quotation etched onto the sculpture bust of him that now stands in San Francisco’s City Hall), “I ask for the movement to continue, because my election gave young people out there hope. You gotta give ’em hope.”

Milk himself had been given hope by his adopted home of San Francisco, where he lived for a couple of years before returning to NYC. When Milk and his boyfriend Scott Smith permanently relocated to San Francisco in 1972, they made their home in Eureka Valley (District 5). This was a community in transition, soon to be renamed the Castro District (or, the Castro). Eureka Valley had been the hub of Scandinavian culture in San Francisco until the 1930s, when it became a primarily working-class Irish neighborhood. In the late 1960s and 1970s, gay men – some of them hippies – settled in the area.

Although this engendered some conflict with the conservative values of the blue-collar residents, here was one of the few places in America where gay people could live in relative freedom. Milk and Smith opened a business, Castro Camera, at 575 Castro Street (near 19th Street). The modest photography shop developed into more of a community center than a successful business. Milk’s gregarious personality and sense of humor won over many of the district’s residents and shop owners. They would go to his store to discuss neighborhood issues and concerns. As a small business owner, Milk reorganized the Castro Village Association of local merchants. So it was that he became known as – his own chosen ID – “the Mayor of Castro Street.” Milk was also a key architect of the annual summertime Castro Street Fair, which drew people from all over the city.

In His Own Write

Every movement needs a hero. As the years pass and the change that hero fought for has been effected, it is common to forget just how much one person made a difference.

Milk screenwriter Dustin Lance Black first heard about Harvey Milk from a mentor while working in theater in the early 1990s. A few years later, Black watched the Academy Award-winning 1984 documentary feature The Times of Harvey Milk. He remembers, “Harvey Milk is giving a speech at the end and he essentially says, ‘Somewhere in Des Moines or San Antonio -‘ which is where I’m from – ‘there’s a young gay person who might open a paper, and it says ‘Homosexual elected in San Francisco’ and know that there’s hope for a better world, there’s hope for a better tomorrow.’

“I just broke down crying because I was very much that kid and he was giving me hope. He was saying, not only are you okay but you can do great things. This was during a really difficult time for the gay community, with the AIDS crisis. And that’s the moment I thought, we have to get that story back out there, we’ve got to continue the message.”

He adds, “I saw Milk as a charismatic leader and a father figure to his people – some of whom might have lost their fathers because of their sexuality – who accomplished so much in a short period of time.

“His legacy is telling people, if you’re gay, don’t closet yourself. You should see yourself as different in a great way, and you should aspire to something. Kids today might not know where these gains came from, but you see them aspiring to be out doctors, lawyers, actors. We’ve lost some ground in the past decade, but Harvey’s message can still save lives.”

A few years later, Black had gained a foothold in film and television, working as a writer, producer, and director. He felt that he could tell the story of the man who has been called “the gay MLK [Martin Luther King Jr.].” However, he notes, “I didn’t have the rights to a book [on Milk, of which there are several] so I started to do research on my own. Several industry folks told me to forget about it, that it was too risky. But my credit card and I pressed on.”

Although a quarter-century had passed, he was glad to discover that many of the people who were close to Milk and had been instrumental in his efforts were still alive. Black notes, “My strategy from the beginning had been to make use of firsthand accounts and stories. I knew it would mean a lot of interviews and trips, but I wanted to find out the details for myself rather than reading it somewhere else – things a writer can’t get out of a book or an article. Finding that the people Harvey surrounded himself with were still alive and doing their thing got me excited. I thought, okay, I can write this.”

The first person Black that met with was Cleve Jones, one of Milk’s protégés and among his closest confidants. An activist on the front lines with Milk, Jones had (and has) led many marches, protests, and rallies. He is the founder of the Names Project and the designer and creator of the Project’s AIDS Quilt, the internationally recognized symbol of the AIDS pandemic.

“[Dustin] Lance and I were introduced by a mutual friend,” Jones says. “I was impressed with him because he’s genuine, kind, and smart – and because he knew who Harvey Milk was.”

When Black told Jones he wanted to pen the story of Milk for the big screen, Jones was immediately on board; he would ultimately remain with the project all through filming, as a historical consultant, on the set every day.

“Boy, is Cleve a gift for a writer,” Black says. “I initially interviewed him over two days and filled eight hours’ worth of little cassette tapes – all of which I transcribed myself, because I couldn’t afford to pay anyone to do it…”

Over the course of a year, while writing on the first season of the television show Big Love, Black would drive up from the program’s Santa Clarita base to San Francisco on weekends. Jones introduced him to – among others – Danny Nicoletta, Anne Kronenberg, Allan Baird, Carol Ruth Silver, Frank Robinson, Tom Ammiano, Jim Rivaldo, Art Agnos, and Michael Wong. All of these people knew Harvey Milk well and had been side-by-side with him in the political and sometimes personal arenas.

But, as Black says, “Initially, there was skepticism from a lot of these people.” Others had come to them before with promises of telling Milk’s story – and that of the gay rights movement in San Francisco – in a feature film, but still it had not happened in the nearly quarter-century since the Oscar-winning documentary. A 1999 Showtime telefilm titled Execution of Justice, based on the stage play of the same name, had concentrated on Dan White (portrayed in the telefilm by Tim Daly) and the slayings of Milk (portrayed by Peter Coyote) and Mayor George Moscone (Stephen Young) rather than on Milk’s life and achievements.

Black admits, “It took a lot to convince some of Harvey’s real-life contemporaries that I was someone who could make this thing happen and that they weren’t wasting their time again. I made these assurances, but I myself wasn’t really sure I could pull it off. Some of them became like family to me and confided in me some painful memories, and I was terrified of letting them down.

“Michael Wong, as a key advisor to Harvey, had kept an extremely detailed diary of his interactions with him. I knew that it would be incredibly valuable; I kept asking him about it. One night after dinner at a restaurant near City Hall, he flopped this big thick stack of photocopied pages at me. He said, ‘Yeah, that’s my journal.’ It was fantastic.”

Wong’s diary helped Black in his intent to tell the significant personal story in addition to the political one. The first-person interviews were further backed up by research; there was a wealth of source material from documents at the San Francisco Public Library’s Gay & Lesbian Center’s Harvey Milk Archives – Scott Smith Collection and the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society’s archives.

If anything, there was too much material; Black says, “You’re always looking for the personal story. I uncovered so many amazing ones that Harvey was directly connected to. But I knew I only had room for maybe a handful of them, out of hundreds.

“I decided that the structure would be Milk’s journey through a movement which he helped to create, from the time [in 1972] that he arrives in San Francisco until his assassination [in 1978]. There is a dramatic framing device with the assassination because I wanted to indicate right away that this was someone very important who something very bad happened to. That starts the clock ticking, which was in Harvey’s head as well; in his recorded will, he voices his strong suspicion that he would be killed. Separately, to his friends, he had said, ‘I don’t think I’ll make it to 50.'”

Just as he felt all of Milk’s 48 years of life couldn’t be covered, Black concentrated on which relationships were key to Milk and which ones were representative of the movement that was changing peoples’ lives. As was so often the case with Milk, the two would converge.

Black muses, “The personal met the political, sometimes beautifully; Harvey Milk had had significant romantic relationships before Scott Smith, but that was the one that helped lift him into office. I don’t know that Harvey could have done it without Scott.

“Harvey was personally connected to why he was doing what he did. It wasn’t just about rights or electoral politics, it was about the fact that he was in love with Scott or he was in love with Jack Lira – and he wanted that to be okay. He didn’t want to be judged for it. He wanted to have the right to be himself, because when he was a young man, and even when he first came to San Francisco, it was against the law to be in a gay relationship, to dance with a man, or to be in a gay bar. So, his is an intensely personal story, even when it is a political one. As a screenwriter, this was one of those rare chances to tell a story where the two are absolutely connected. It was politics for the sake of love.”

The Direct Approach(es)

To put Harvey Milk into cinematic narrative terms, Dustin Lance Black went through numerous screenplay drafts over a nearly four-year period. “I gave up a lot of nights and weekends,” he remembers. “During the week, it was, Big Love until 6 or 7 at night, then Milk from 7 to midnight.”

Once he was done, he reveals, “I didn’t have any money to make the movie myself, and I had to get everyone to sign off on my using their stories.'”

“I thought Lance’s script was beautiful,” Cleve Jones says. “It had a very simple, elegant structure. Harvey’s voice was clear in it; I could hear Harvey saying the words Lance had written.

“I would say to Lance, ‘When you’re ready, I’ve got a director for you,’ but I didn’t tell him who it was. I knew that if my friend Gus were the director, the film really would be about Harvey and not about the director.”

Black says, “When Cleve told me his friend who wanted to direct was Gus Van Sant, I said, ‘Oh, that’s good!'”

True to his word, Jones called Van Sant and set up a meeting. Black declined to give him the script at that meeting until he did one more draft, at which point it was sent to the Oscar-nominated director in Portland. A week and a half later, Van Sant called Black and said, “Let’s make this movie.”

Van Sant reflects, “The Times of Harvey Milk had set the bar pretty high, but I felt a dramatic version would be an important continuation. I knew pretty much about the story at that point I got this script, and there was always a difficulty in telling it because of the many elements of Harvey’s life and the many other intersecting stories at Castro Camera. But Lance got it in line and wrote a succinct script that was largely about the politics and less about the day-to-day lives of the characters.

“Harvey Milk is one of the more illustrious gay activists, and since he died in the line of duty, he has achieved sainthood in the gay world. One reason to make this film was for younger people who weren’t around during his time; to remember him, and to learn about him.”

Given that many of the director’s films have had as their protagonists people who are not being given their quarter by society, Van Sant allows that Harvey Milk “fits in with many of those other characters’ outside-the-mainstream status. Yet this is also the story of someone living in the mainstream, or at least my mainstream.”

Black was friends with the producing team of Dan Jinks and Bruce Cohen, Academy Award winners for American Beauty. Both knew of Milk when they were growing up; Jinks’ father had been editor of The San Jose Mercury-News, which followed Milk’s campaigns and triumphs.

Jinks notes, “I read that Lance had written a screenplay about Harvey Milk and that Gus Van Sant would be directing it, so I called Lance up to congratulate him and he said, ‘You know, we don’t have a producer. Would you be interested in reading this?’ I said, ‘Are you kidding? Absolutely!’

“I mean, here’s a guy who made a difference in the world, fighting against prejudice at an important time in the history of gay rights. The movement had a leader in place who was effective at stopping something that really needed to be stopped.”

Cohen adds, “When we read the script, we were unbelievably excited because we thought, ‘Finally! This important story about a hero is going to get to the screen with a strong script and the perfect person to direct it, and if we can help to get it told that will be incredible.’ It’s both an intimate and an epic story.

“We felt that the film could be moving and entertaining, whether you know Harvey’s story or not. This man was not your average politician; he came out to San Francisco with Scott Smith with the goal of expressing himself and living his life and being out and creating this new world for himself there. He didn’t have a plan to go into politics, but he felt he could make a difference. And here we are, in a presidential election year where the theme is change…”

Jinks remarks, “One of the benchmarks of the script is authenticity, since Lance researched it extremely well. The script tells Harvey’s heroic story so powerfully – but also hilariously, and sexily. Combine that with the confirmed involvement of a world-class filmmaker, and we immediately said, ‘We have to be a part of this.'”

Jinks, Cohen, Black, and Van Sant convened to talk about their next steps. Van Sant discussed his plan to use archival and news footage at certain points in the movie, not merely before or during the end credits as most biopics do, an inspiration that Jinks found “marvelous.”

For instance, the actual announcement by Dianne Feinstein (then the president of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, now a U.S. Senator) on the steps of City Hall of the assassinations of Milk and Mayor Moscone “is such an iconic image that we didn’t want to attempt recreating it,” says Jinks. Actress Ashlee Temple was cast as Feinstein for newly filmed narrative/linking scenes, but that 1978 announcement to the press was, says Cohen, “such a powerful moment in history that we decided the best way to convey the shock and horror of that moment was to let it speak for itself.”

Joining the coalescing project was the new production and financing company Groundswell Productions. Groundswell principal and founder Michael London, an Academy Award nominee for Sideways, had found himself drawn in by the personal and historical detail captured in the screenplay.

He remarks, “In reading Lance’s script, I brought my own history to it. I had gone to college in the Bay Area and spent a lot of time there. I was aware of how essential Harvey Milk was to the city, and to the community that was building there at the time.

“He was an extraordinary American hero – at a time when we didn’t have a lot of them; we don’t today, either. Very few times in your career do you get the opportunity to be involved with a story so powerful and timely with artists of the caliber of Gus Van Sant and Sean Penn.”

Penn had leapt to the forefront of everyone’s minds as the project coalesced. Cohen notes, “He has this way of just inhabiting a character where you couldn’t find the actor underneath if you tried.”

Jinks adds, “Sean likes to be surprising in everything he does, and I think he can do anything.”

Van Sant knew the Oscar-winning actor – who now lives in the Bay Area – and sent the script to him. Penn responded even quicker to the script than Van Sant had, and within a week, Black and Van Sant were meeting with him to confirm the project. Penn wanted assurances that the filmmaking team would be as authentic with Milk’s personal relationships as they were with his politics.

Black admits, “We were mindful of whether a lead actor would take risks. But Sean said ‘Let’s do it right. Let’s tell it like it is.’ Sean made a real effort to make it as true as possible. He is dedicated to accuracy, and he wound up completely embodying the mind and spirit of Harvey Milk.”

Jones states, “When I heard that Sean Penn had agreed to do it, I started whooping and hollering and running around my living room like a madman. He’s one of the great actors of our time.”

Jinks said, “Every day on the set, it became this thrill for all of us to see Sean transform himself into somebody who was really so much Harvey. The people who were in Harvey’s life and have been involved in the film were astonished at the transformation.”

Van Sant comments, “Sean brings real old-time intense excellence in portraying a character on the screen.”

Cohen says, “Milk lifts and soars on Sean Penn’s performance as Harvey Milk, whom he embodies. There were moments where it was important to Sean that he deliver a certain line or speech exactly as Harvey did it. On the set, I had goosebumps watching that happen.”

Penn remarks, “There was not only an excellent script to be guided by here. There was also a good amount of archival material. I fell in love with Harvey, with this person, this spirit of this human being, which transcended my own agenda as an actor.

“Gus Van Sant is a director who never makes a bad movie, so as an actor, one feels enormous faith in his process.”

The production came fully together once Focus Features committed to co-finance the movie with Groundswell, and to take worldwide distribution rights. London comments, “Everyone at Groundswell and Focus had an emotional connection to the story; we all felt the urgency to tell it.”

Real Life / Reel Life

Michael London notes, “A rule in the making of the movie was, if people responded without equivocation to the project and wanted to be involved, then we wanted them.”

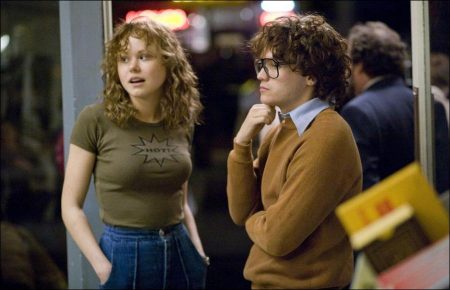

Given just how many real-life personages would be portrayed on-screen, casting would be even more crucial than usual to a feature film. Francine Maisler was engaged as casting director.

Bruce Cohen elaborates, “Actors wanted to be part of the film that finally told Harvey Milk’s story, and were also jumping at the chance to work with Gus and Sean. We cast sexual-preference-blind- which is to say, we have straight actors playing gay people, gay actors playing straight people, gay actors playing gay people, and straight actors playing straight people. We felt that for this movie to have not included all those different permutations would have been a mistake.”

Beyond even the sexual-preference-blind casting, the roster proved to be full of surprises. As Dustin Lance Black had found, many of the real-life people who knew Milk best were still alive; therefore, the actors were able to spend time getting to know the people they were about to portray. In a testament to Milk’s legacy and to the filmmakers’ enthusiasm and care, Milk’s long-ago friends and compadres spent a significant amount of time on the set. Cohen marvels, “These people have helped our movie come together and come to life.”

Black reflects, “Having already spent so much time with them during the research, one of my prime goals during production was to make sure they got involved with everyone as much as possible, whether it was in the wardrobe process or just being there on the set.”

Some ended up in front of the cameras, too; Dan Jinks remembers, “Gus said ‘Why don’t we get the real Tom Ammiano to play the role of Tom Ammiano?’ Then he had the idea to get Frank Robinson, Harvey’s speechwriter, to play himself hanging out in the camera shop and participating in marches and rallies. Then Harvey’s Teamsters Union ally Allan Baird agreed to play himself when Gus asked him to. They were in Harvey’s world back in the day, and now would be again.”

Others played not themselves but people close to them and/or Milk. While Emile Hirsch plays Cleve Jones, the real-life Jones plays a cameo role as another real-life activist and Milk supporter, Don Amador. Carol Ruth Silver plays Thelma, a volunteer staffer through all of Milk’s campaigns for supervisor. Silver (now director of Prisoner Legal Services for the City and County of San Francisco) herself served on the Board of Supervisors and was staunchly allied with Milk; actress Wendy King portrays Silver in the City Hall sequences in the movie.

Over the years, Gus Van Sant has worked with all manner of actors and non-actors. He offers, “Whether they are seasoned pros or newcomers, as a director I talk to them in a similar way; we discuss stage direction, emotion, other characters, and the overall story. Part of this is because I was self-taught and have always used non-actors in my films.”

Jim Rivaldo, the political consultant who was such a key architect of Milk’s campaigns, had met not only with Black but also with his on-screen portrayer Brandon Boyce before he died in October 2007 (three months before filming began). Boyce remembers Rivaldo as having “a very dry sense of humor. In researching his life, I found that he had a madcap spirit, but he backed up what he believed with his actions.”

Rivaldo’s longtime colleague, Dick Pabich, had passed away several years prior to the start of filming on Milk. A vital strategist on Milk’s campaigns, Pabich also worked in City Hall with him and Kronenberg. Actor Joseph Cross, cast as Pabich, marvels that “Jim and Dick did things with the ads for Milk’s campaigns that hadn’t been seen or done before. Their company, Rivaldo/Pabich and Friends, went on to work with all sorts of political underdogs. Brandon Boyce and I worked closely together on establishing a dynamic for them.

“Most helpfully, Anne Kronenberg had me over for dinner and talked to me about Dick. She said that he was super-smart, didn’t have time for anyone’s bulls-t, and loved wearing very nice clothes. Meeting Anne, and Cleve and Danny Nicoletta, I was able to understand the power of the community and also how excited and scared they all were during those times. Watching this movie, I think that people are going to understand a lot more about gay culture and the fight for their rights.”

For all the real-life figures who had shared their stories with Black and lent their support to the project, Milk was like a time machine back to the birth of a movement in which they were a part. Some of them have moved on to different places and parts of their lives. Milk supporter Gilbert Baker, the creator of the LGBT movement’s iconic and inspiring Rainbow Flag, now lives in New York. Cleve Jones resides in Palm Springs. Anne Kronenberg remained in San Francisco and is now Deputy Director for Administration and Planning of the city’s Department of Public Health.

Bringing things perhaps fullest circle is Tom Ammiano. Once a schoolteacher who fought back and came out when targeted by the Proposition 6 initiative that Milk and his colleagues worked tirelessly to successfully defeat, Ammiano himself is now a San Francisco city supervisor – as Milk was.

Ammiano reports, “Sean would look and sound more and more like Harvey every time I saw and heard him – especially with Harvey’s New York accent.”

Similarly, Baker filmed a small cameo role (more or less playing himself, as a Milk supporter) and visited the set, but he says that when he “saw Sean, I had to stop in my tracks. For a minute I thought I was looking at Harvey. I looked into his eyes, and I thought he’s really got that sparkle, he’s got that charisma.

“Harvey would call me up and say, ‘I need a banner for a march,’ and I would make one. It’s funny; here I was making them again in San Francisco for this movie! My friends who call me ‘the gay Betsy Ross’ say, ‘You never sewed that well in 1978.'”

Kronenberg confides, “I didn’t know whether I could even be on the set, whether it would be too painful. It was the exact opposite. For three decades, I had put a wall up because of losing my friend, my mentor, my father figure. But by blocking the pain, I had blocked all of these great times that I was now able to relive. Sean would take my breath away – on the set, he looked like Harvey and he had the mannerisms down.

“When they filmed the victory election night scene, Gus said, ‘Come on, Anne, you have to be in the scene.’ So there I was, partying on election night 1977 for a second time. How many people get to relive their lives 30 years later?”

Dan Jinks marvels, “All of them would come by and share with our cast what happened, and how it was. They would sit down with our wardrobe department and say, ‘Well, this is what I wore on that day,’ or they would say about a scene, ‘I was standing over there in Castro Camera that day.’ Sometimes they would have pictures.”

Van Sant was careful to integrate this fidelity with his style of filmmaking. He clarifies, “The way I make scenes seem real is to try and not be too overly dramatic. This way, the moment seems like it’s really happening. It’s a naturalistic quality that is just my style; for me, it’s what makes a scene work.”

Cohen adds, “We were already striving for as true-to-life a recreation of the story as possible in the sets, the costumes, the performances, and the dialogue. Since these are the people who have very detailed, sometimes painful but also beautiful memories of what really happened, that helped us recreate so much more; there was this whole other layer of meaning and truth and beauty in making Milk that you don’t usually get on projects. It was extraordinary.”

One of the most extraordinary days on location came towards the end of filming; over 3,000 volunteer extras from around the Bay Area showed up to recreate the 1978 Gay Freedom Day Parade, where the recently elected Milk and the debuting Rainbow Flag were both prominent.

Kronenberg recalled how she drove Milk (who was up top, not seated next to her) in his old Volvo down Market Street, with an emergency escape route to the nearest hospital – should he be attacked or shot – already mapped out. Instead, a different threat materialized that day; “Some queen with a snake came running up to the car to show it to Harvey. I hate snakes, and was so scared that when the snake started to slither down through the sunroof, I panicked and gunned the engine!”

Frank Robinson’s career as a writer has encompassed not only numerous books (including The Glass Inferno, used as a basis for the blockbuster movie The Towering Inferno) but also speeches for Harvey Milk. A point of pride came during filming while he sat on steps behind a podium where Sean Penn was delivering Milk’s famous speech in which he taunts anti-gay crusader Anita Bryant by opening with “My name is Harvey Milk, and I want to recruit you.” Hearing it said aloud anew, Robinson grinned and said, “I wrote that!”

On another day, there was a recreation of a lavish birthday party for Milk – which would be his last. Although Milk loved opera, 1970s disco icon Sylvester (played in the film by performance artist Mark Martinez, a.k.a. Flava, in his feature debut) performed his classic “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” for his friend Milk at the party. Those who were there also remember how the guest of honor had a joke played on him – getting pies in the face – that he had always enjoyed playing on others. Danny Nicoletta remembers, “Harvey got five pies in his face that night; I was one of the people throwing them. On the set, I sat in the corner weeping, because to hear Sylvester’s music again and watch all this was amazing and terribly poignant.”

Similarly, reports Jones, “I cried every day during the first week of production. When Josh Brolin walked by me as Dan White, it was horrifying. He said to me, ‘The look on your face tells me everything I need to know.'”

Brolin reflects, “I read the script and cried at the end. This is a love story, a civil rights story, and a coming-of-age story. I then watched the documentary feature with my daughter and was extremely moved by that. I said yes right away to doing this movie. Harvey Milk was willing to put himself in harm’s way for the betterment of people’s moment on earth, and we should not forget how George Moscone made a lot of things happen for Harvey.

“What had a huge impact on me was speaking to family members and also to Frank Falzon, who was a friend of Dan’s and – as homicide inspector -took his confession. I think Dan was kind of myopic in the way that he only saw what was right in front of him; sadly, he didn’t have that macro picture to understand politics for what they were, to understand that this may not be your time this year. Other things were coming up; women’s lib, gay rights. If he waited it out and took a back seat for a little while, then he probably could have made a major difference for his constituents in the future. He had insecurities that were very deep.”

Department head make-up Steven E. Anderson notes, “I created a pair of sideburns for Josh that fit him, his hair color, and the shape of his face – yet pushed him into Dan White. Josh would go through the hair department, have his hair dressed in that wonderful little side part. I would widen his forehead, bring out his eyebrows, and the minute I would stick the sideburns on, he was there. He went to a dark place and became Dan.”

London remarks, “Dan White is a mystery, yet Josh got under his skin. A key for him was that Dan really wanted to be liked.”

Cohen offers, “Josh brings a humanity to Dan. We didn’t want any of these people to be portrayed one-dimensionally. These were living, breathing human beings and we wanted that.”

Similarly, Diego Luna acknowledges that in playing Milk’s (last) lover, the late Jack Lira, “I wanted to portray him in a fair way. I know a lot about him without really knowing him, because every Mexican goes through a struggle here; imagine being gay and Mexican at that time. I believe he was a bit lost, and searching for someone to take care of him. I decided not to contact his family, but I talked a lot with Danny Nicoletta and Cleve Jones and then developed my own take on who Jack was.

“Sean Penn was so generous to me, and knows what’s good for the film. He understands what acting is about; it’s about communicating. I could find him there every time in our scenes together.”

Having recently been directed by Penn to great acclaim in Into the Wild, Emile Hirsch would now again be collaborating with him, this time as fellow actors. Hirsch states, “Working with Sean was incredible. Because of our intense relationship on Into the Wild, I wondered what it would be like suddenly acting with him, because at that point he was only a director to me. But all the things that made him brilliant as a director, like his instincts and insight, he brought to every second of every scene – and instead of me alone so often like I was in Into the Wild, I had someone to play with.”

In Into the Wild and other previous features, Hirsch had played real-life figures. But, he notes, Milk “was the first time that I was ever able to portray someone who was also on the set every day. Any question I had was just a few words away from being answered at all times. Cleve Jones is endlessly funny and deeply caring about everyone around him. The man just has a magnetic charisma; he can go up to the most uptight conservative guy, and after five minutes they’ll both be having a laugh.”

Jinks reports, “Even off-screen, Emile would be doing Cleve-isms, and when he would improvise a bit on-screen it would be something that we knew the real Cleve would say!”

London comments, “Emile is such a bold, daring actor. He’s come of age before our eyes on film. On this movie, he went after the challenge of learning about, from, and with Cleve. He took in the essence of what Cleve is about. The portrayal is seamless and authentic.”

The lone prominent female role in the story went to Alison Pill. Jinks states, “I’ve followed her career for a few years now, especially in the New York theater world. She’s so gifted. A lot of people haven’t heard of her yet, but they will. She’s great as Anne Kronenberg.”

Pill was able to spend plenty of time with the woman she was portraying. The actress marvels, “Anne is a powerhouse. For the scenes where I’m playing her coming to work on the campaign, she advised me, ‘You have to walk in there and own it; talk to these people like you know what you’re doing!’ She had to fake it for a little while, but then figured it out and became incredibly organized. Part of that came from meeting with Harvey for two hours early in the morning each day, before everyone else came in.

“She and I talked about what it’s like coming into a group that is already so settled. Now, I had met a lot of the actors when I first came for rehearsals, but for the first couple of weeks I wasn’t filming. So, I too was coming into a group of people as the only girl and had no idea what to expect. Like political campaigns, film sets have odd hours and on this one we had a great deal of fun in the trenches together; sometimes we’d just want to watch Sean Penn work but we’d have to remember that we too were in the scenes.”

Black reports, “Anne, Cleve, and all the real-life people created a camaraderie with and amongst our cast that mirrored what must have existed in the real shop back then.”

For another of the real-life portrayals, Lucas Grabeel, known to millions for his role in the High School Musical features, impressed the filmmakers at his audition for the role of Danny Nicoletta, and continued to do so through all phases of production. Black reports, “One weekend day, we did a read-through of the script before several actors had arrived on location. I read the stage directions – and Lucas, in addition to his own, played every role in the script for those actors that weren’t there. He then proved even better during filming than at the audition – and the bar was high, what with Danny on the set watching him…”

Grabeel notes, “This project was the first knowledge I’d gained of Harvey Milk. What drew me to his story was that he fought for everyone being treated equally. As soon as I booked the part, I read up on the history and did my research. Danny, in his photographs, has this unique style of capturing the essence of people and events. I was extremely fortunate; seeing his pictures and talking with him helped me get a sense of what the Castro was like in the 1970s. It was a place where it wasn’t about believing what everyone else thought; it was about believing in yourself.

“On the set, I started taking a few pictures myself. I’m using the same kind of 35mm camera that Danny used back in the day. I was worried they were all going to come out completely dark, but actually they turned out pretty well!”

Another franchise star, the Spider-Man movies’ James Franco, portrays the late Scott Smith. Milk’s most loyal lover and supporter “was called ‘the widow Milk’ by some,” notes the actor. “After Harvey was assassinated, a lot of Scott’s life became about preserving Harvey’s memory. [The Times of Harvey Milk director] Rob Epstein showed me interview footage of Scott that didn’t make the final cut of the documentary, and I got a good sense of who he was. They had broken up by the time Harvey was elected, but they still cared about each other; Harvey thanked Scott in his election-night speech.”

Nicoletta remembers, “My remembrance is that Harvey and Scott were profoundly and poignantly in love, but it was also very tumultuous. The pressures of the campaigns would manifest in extreme passionate arguing.”

Jinks remarks, “I think audiences will be surprised by James in this role, which he plays so sensitively. Part of the emotional core of Milk is the relationship between Scott and Harvey, and how it was affected by Harvey’s political career.”

Franco states, “Harvey Milk was one of the brave ones, and making the film where the events happened was an incredible experience. Gus and Sean have been heroes of mine for years, so as an actor I couldn’t have asked for anything more.”

As a non-actor, Robinson wound up getting a Screen Actors Guild card on Milk in part because, he reveals, “Franco is a real agent provocateur; I was in the scenes in the shop to be seen, not heard, but he would nudge my foot and address me – ‘Hey, Frank…’ – and, having written dialogue for 50 years, it would come out naturally…”

Upon being cast as the city’s mayor, Victor Garber did research on his role and found “the whole period of history just so intriguing. I felt honored to be a part of this movie and to be playing an extraordinary man like George Moscone. He believed in freedom for all, and civil rights.

“Individuality must be celebrated, and people must be reminded of that. There is still a struggle for so many young people today. Hopefully, Milk will awaken the need for people to do something against intolerance and bigotry.”

Kelvin Yu, cast as Milk’s close advisor Michael Wong, spent time with the man he would be portraying but also availed himself of the journal that had been such a help to Black. The actor reports, “It’s like 370 pages, all in first person, and Michael’s bulls-t meter is perfect. In Harvey, he saw somebody who was the real thing.

“The journal provided Michael’s own point of view, and I talked to other people as well. Michael was a rebel, and he did it in ways that are more substantial and less cosmetic than what people would think being a rebel is like. He was galvanized to use the political system to fight for civil rights, with voting and with democracy.”

Wong, who emphasizes that today he “is not interested in any politics,” states simply, “I hope the film will show that you can be an ordinary person who happens to be gay and who can do something extraordinary like Harvey Milk did.”

Hirsch adds, “Milk will inspire anyone who has ever been hard up without a spot of luck in sight, or has ever felt like an underdog.”

Rolling

Dustin Lance Black muses, “The first day of shooting was the day I finally breathed a sigh of relief. Something I had started four years earlier was coming to fruition. We had done it; it was really happening. I started crying when we saw a rainbow that day. Cleve Jones had tears in his eyes, too.”

Jones elaborates, “It was the worst possible morning, drenching and cold. We were out in the Excelsior District [Dan White’s district] to shoot the first scene. Two minutes before the cameras were to start rolling, the clouds parted, the sun came out and this enormous rainbow appeared over the set. A sign, I thought.”

Gus Van Sant and his frequent cinematographer Harris Savides were unfazed by weather concerns – and not always bound by convention. Embarking on their fifth movie together, Van Sant notes, “Every picture that Harris and I have done has been in a journey in terms of our figuring out how we’ll be filming it. For Milk, we knew it would be different than the smaller films we’ve made together.”

Despite the larger scale, the director and cinematographer did not avail themselves of storyboards, and hewed to their collaborative and exploratory approach.

Van Sant adds, “Each time, I think we start out knowing that the possibilities are endless; we then pare down which possibilities are interesting to us. Sometimes we reference films or photos. We consider everything, and end up with a handful of ideas we like.

“Frederick Wiseman was an inspiration for us on Milk, and was on our earlier pictures Elephant and Last Days, too. The reason that we like him is that he is usually shooting something completely compelling and somewhat rough, because the situations he is filming in don’t allow elaborate equipment or lights. Yet he is completely relaxed in the face of very intense places and people. Now, Wiseman is a big influence, but we have a few others – you can see a little Robert Flaherty in Milk.”

Bruce Cohen reports, “Certainly, some of the excitement of making Milk was recapturing the look of the 1970s, as part of bringing an authentic feel to the film. Gus said, ‘How about Harris Savides’ and we said, ‘Yes, please.’ We knew he had done brilliant work not just with Gus, but also recreating landscapes of the 1970s in American Gangster – also with Josh Brolin – and Zodiac. With Harris filming this movie, you are going to feel that you are a part of something that is happening right now, not sitting back and saying ‘Oh, this happened a long time ago.'”

On the set, Black reports, “I learned so much from watching Gus. His style is different than any other director I’ve worked with – it’s very organic; he steps back and understands how to let things happen and find the unexpected. He allows the actors and artists around him to discover things.”

Dan Jinks remarks, “This is not a director who says things necessarily just to be heard. He says things when it is necessary to – and, as a result, everybody listens. It may be just a couple of words, but you’ll then know what he’s looking for.”

Alison Pill enthuses, “It’s sort of flying by the seat of your pants. A lot of times two cameras will be filming at once. With the huge element of trust, it’s the most inspiring way to work because you have to be present in every single moment during the entire day.”

Emile Hirsch offers, “Gus makes you use your own legs as an actor, instead of being a crutch that never lets you find them. Because of that, his actors are always pushed to be brave and trust their instincts like they’ve never done before. He is extraordinary to work with.”

On Location

Milk was filmed entirely on location in San Francisco (where Harris Savides had also worked extensively just a couple of years prior as the cinematographer of Zodiac) with a home base at Treasure Island. For the filmmakers, it couldn’t have been done anywhere else. “The spirit and energy of this film is San Francisco,” Dustin Lance Black says. “The film was made the right way, in the right place.”

Mayor Gavin Newsom and the San Francisco Film Commission worked closely with the filmmakers, coordinating with executive producer and unit production manager Barbara A. Hall to ensure that the production had every access to the city. This included filming in and at City Hall; however, the production respectfully declined the mayor’s offer to film in his own office, mindful of the city’s need for him to be in it. Milk further benefited from the city’s film production incentive program, “Scene in San Francisco,” which Mayor Newsom had signed into legislation in May 2006. The mayor cites Harvey Milk’s story as one that “must be told. His spirit and legacy manifest today in real change.”

Bruce Cohen adds, “All of us felt from the very beginning that San Francisco was a character in the story. The story changed the city forever, and is woven into its history and its fabric.

“We went looking for a place we could recreate Castro Camera, and we ended up going to the exact location where it used to be, at 575 Castro Street. We went into this shop and said, ‘Can we kick you all out for nine weeks and turn this back into Harvey’s camera store the way it looked in the 1970’s, and film here?’ It was like taking history and making it feel like it was happening again right now.”

The owners of 575 Castro Street, which is now a gift shop called Given, were happy to comply. Production designer Bill Groom and his team of art directors and set decorators protectively “built fake walls about three inches in,” Dan Jinks reveals. “But the look is exactly the way that Castro Camera looked back then.”

Upon seeing the complete re-creation, some people who were there the first time had highly emotional reactions. Michael Wong, whose diary had been such a boon to Black during the screenwriting, was one; Black remembers, “I called Michael to come see the camera shop. I knew he probably didn’t want to, but that he would later regret it if he didn’t. He came in and walked around. When he got to the back and saw the printing press that Bill Groom had made sure was the exact model that Harvey had been lent for the victorious election, Michael stepped outside and started to cry, and he is not a particularly emotional guy. He turned and hugged me and said ‘Thank you,’ and that got my waterworks going too. It was one of the most meaningful moments for me on Milk.”

Members of Milk’s inner circle found themselves hanging out at “Castro Camera” all over again. James Franco remembers, “They would walk in, and they would get a look in their eyes; it was almost like they were time-traveling. This one shop played such an incredible part in the worldwide gay movement.”

Danny Nicoletta notes, “Propelled by the urgency of the politics of the time, the Castro was a very vibrant, socio-artistic epicenter. The camera store reflected that. You might come in to drop off film, and then stay to talk about opera or politics, or to put up a poster saying come in and register to vote.”

Groom and his staff availed themselves of the research and recollections. He states, “We all felt very fortunate to be part of this project, and we shared a responsibility to tell this story as truthfully as we could. Over and over, I would try to catch Lance on a possible inaccuracy in the script – but I never could. He was so well-researched that he became the person we went to with questions, but all of the people who were with us and were around then had memories that helped us recreate everything. We were working already from thousands of photographs and hours of film and video, but everybody helped us interpret those materials. There were a lot of ‘aha!’ moments along the way when someone stepped in and put the pieces together.

“We would even dress the insides of drawers so that the actors would be surrounded by welcoming atmosphere and things they could make use of – especially since Gus Van Sant’s style can be improvisational, like jazz.”

Groom marvels, “People who have been in the Castro for a very long time just started coming forward with, not only photographs, but objects from Harvey’s camera store; actual signs that were hanging in the windows, for instance.”

But much had to be re-created, too. Groom remarks, “The camera store is full of movie film, print paper, developing chemicals, and materials that doesn’t exist anymore. All of those labels had to be created. So we had a graphic designer and printer in our department and we were producing all of that material in-house.”

Set decorator Barbara Munch, herself a Bay Area resident, adds, “I have a warehouse full of things, and everyone would say to me that it would never be used on a film. On Milk, we used it all! We built certain pieces of furniture to match the research. Other pieces we found, like the red Art Deco couch that everybody would hang out on.”

The department did its job so well that, as art director Charlie Beal laughs, “One day, three young women tourists came in wanting to buy a battery for their camera. I suddenly felt like Harvey was there, and was about to try to get them to register to vote.”

Michael London affirms, “Bill, Barbara, Charlie, and the crew did the best kind of work – not showing off, but helping everyone live inside that world. Being in the camera store was a highlight of being on the set; it brought back some vivid memories of 1978 San Francisco.”

Cohen reports, “The Castro Street merchant’s association and its members were so supportive. Luckily for us, very little on Harvey’s end of the block had changed structurally.” Some shops had both changed and stayed the same; Swirl wine shop was reverse-aged into McConnelly Wine & Liquors, for a scene where Milk brings in gay customers to unify the neighborhood.

Groom adds, “San Francisco’s Gay and Lesbian Archives houses photographs that were a vast resource. We dressed two blocks of the Castro, about 50 storefronts from 17th Street to 19th Street. Different sections of the block were dressed differently, because we were covering six years in San Francisco’s history. Some sections of certain blocks were dressed for 1972 and 1973, while other sections were dressed for 1976 or 1977.”

Jinks remarks, “Gus didn’t want anything inexact or incorrect. If we had a sign for a business up, it was because that business was open in the year the scene was taking place – per the research.”

Costume designer Danny Glicker and his staff made copious use of the various collections of photographs, too. Glicker notes, “From a strictly visual standpoint, my guardian angel was Danny Nicoletta. In the 1970s, San Francisco was the place where cultural change was exploding and constantly evolving. The energy there just attracted more energy. As a costume designer, this was an enormously appealing challenge. It was important to be detail-driven as opposed to having a grandiose concept.

“I love old clothes and whenever possible will use the real thing. Getting skintight ’70s jeans for everyone was a huge challenge because bodies have evolved since. I went to some serious dumps to look for jeans – and sometimes we had to pay large amounts of money to get beautifully broken-in Levi’s from the 1970s!”

Glicker adds, “I feel that the clothes give us insight into why someone wants to look good and what they’re hoping to achieve by dressing a certain way. It wasn’t all about glamour then, but a sense of openness.

“Harvey’s relationship with his clothes was not that different from a lot of people’s in the Castro; they had very little money. One of the first things that Cleve Jones told me, and this is reflected in the movie, is that Harvey always had the same few items of clothing on. When he needed more clothing for his political career, he bought a couple of suits at secondhand stores and would wear them consistently. His shoes would have holes in them, and when he was being carried out of his office after being assassinated, Cleve saw shoes on with holes in them and knew it was Harvey. We had an entire book, a binder, on Harvey. Based on the research, if a scene corresponded with an actual outfit, we labeled it. I had a copy and Sean Penn had a copy.

The other actors were sparked by their research, too. Glicker says, “I looked forward to the actors coming to me with ideas. Some of them wore items from the real people they were portraying. For instance, Alison Pill in many scenes wears an earring that Anne Kronenberg wore every day back then; Lucas Grabeel wore one of Danny Nicoletta’s own vests; and, perhaps most touchingly, George Moscone’s son Jonathan brought one of his father’s ties to the set so that Victor Garber could wear it for the scene in which the mayor swears in Harvey as supervisor.”

Today’s San Franciscans found part of their city going back in time for weeks on end. Baker’s Rainbow Flag, which now adorns streetlights, had to be temporarily removed or covered up because much of the film takes place prior to its 1978 unveiling. Seeing resurrected hot spots like Aquarius Records, China Court, and Toad Hall, people did double takes. Stories were told, memories were exchanged, and the excitement of a time of change and realized potential was palpably recalled. As ever, Harvey Milk was bringing people together.

The Castro Theatre movie house had its façade and sign redressed to look as it did during the 1970s; in a more permanent upgrade, the neon marquee was repainted and restored – and the cinema now looks better than it has in 20 years.

With Rob Epstein’s help, the production arranged a screening of a restored 35mm print of The Times of Harvey Milk at the Castro Theatre (where the film had first screened for San Franciscans in 1984) for extras just prior to filming of a march and rally led by Milk.

On February 8th, 2008, one of the most important sequences was filmed. This was a re-creation of the peaceful candlelight vigil march which united tens of thousands of San Franciscans – of all ages, races, and sexual orientations – as they struggled to cope with their shock, grief, and rage over the murders of Harvey Milk and George Moscone by Dan White.

The production was able to engage several thousand extras. There were a number of people in the march re-creation who had marched the night of November 27th, 1978; and, as they had 30 years prior, Cleve Jones and Gilbert Baker were among those putting out calls for San Franciscans to participate.

London says, “It was as if the city had stopped again, 30 years later. There was an outpouring of people. It wasn’t people who just wanted to be on film; from the moment they started walking and the cameras started rolling, you felt why they were there. You felt the loss, and the actors did, too.”

Jones remembers that November night in 1978, when “we marched in absolute silence down Market Street. It was gay and straight, black and brown and white, young and old, people who were so devastated by the loss of these two fine men who had loved this city so deeply. Every year on November 27th, we have re-enacted the candlelight march.

“We made history on those streets and now we’ve done it again. I look into the crowds and recognize some people from 30 years ago. It’s bittersweet, because this neighborhood was decimated during the AIDS pandemic; there are thousands upon thousands of people who marched with us then and who are no longer with us. I’m so glad to be alive and to see that this movie finally happened.”

Gus Van Sant marvels, “It was wonderful to have the help of so many San Franciscans. They really got into it and were an enormous help.

“Thank you, San Francisco.”

Milk’s Legacy Today

The cumulative effects of Harvey Milk’s breakthroughs remain in the culture and politics of today. The gay rights movement has come a long way, but the pendulum continues to swing.

Some countries (Canada, Spain, Denmark) have legalized same-sex marriages. Some American states like Massachusetts and California have followed suit. But in an election year, much is still to be decided – with people’s lives and loves to be directly affected.

Outgoing U.S. President George W. Bush supported the Federal Marriage Amendment that would have changed the U.S. Constitution to prohibit the legal recognition of same-sex marriages. The proposal did not make it off the Senate floor.

Dan Jinks comments, “You hear about kids who are coming out to their parents in high school, and you hear about out people running for public office. How far we have come in 30 years is largely due to courageous people like Harvey Milk.”

Bruce Cohen remarks, “Harvey Milk’s story shows what one man can accomplish, and also shows how far we still have to go.”

Dustin Lance Black adds, “For me, Harvey’s greatest legacy is that his story of hope has saved, and will continue to save, lives. I consider myself to be one of them. There are still kids out there who are coming out, and who need to know that there are gay heroes and gay icons. It is my hope that Milk further solidifies Harvey Milk’s legacy of saving lives.”

Cleve Jones states, “It is important for us to know our history and, as much as we can, to learn from it. I am sometimes fearful that the new generation is so unaware of how many people had to struggle so long and so hard to have the beginning of freedom that we have now, though our struggle is not complete yet. History is full of examples where people who thought they were free, thought they were prosperous, thought they were secure, found out overnight that they were living in a fool’s paradise. We are winning, yet all this could be taken away in the blink of an eye.”

Memories of Milk

Harvey Milk: [1977 speech;] I was elected to open up a dialogue for the sensitivity of all people, of all the problems. The problems that affect this city affect all of us.

[1978 Gay Freedom Day Parade speech;] Wake up, America…No more racism, no more sexism, no more ageism, no more hatred…No more will we be harassed, no more will we stay in our closet…No more!

[1977 recorded will;] I fully realize that a person who stands for what I stand for – an activist, a gay activist – becomes a target or the potential target for somebody who is insecure, terrified, afraid, or very disturbed themselves.

Frank Robinson: He considered himself to be in a safe house when he was in City Hall. There were cops all around; who was going to plug him, another supervisor? Yeah, you bet your a–, another supervisor.

Cleve Jones: He made that [1977 recorded will] audiotape to be played in the event of his assassination. I teased him for it, but he foresaw clearly what was going to happen.

When I was standing in that lake of candles in Civic Center Plaza the night Harvey was killed, I made a promise to myself that I would do whatever I could for the rest of my life to make sure that his name was remembered.

What I would like people to know is that Harvey was an ordinary man. He was not a saint. He was not a genius. His personal life was often in disarray. He died penniless. And yet, by his example and by his actions, he most certainly changed the world. And again we see that history is full of examples of ordinary men and women who, by speaking the truth, by their own courage, do in fact change the world. At this time in our country’s history, people of all ages, races, and backgrounds need to understand what one person can do.

Gilbert Baker: We all felt that we were going to change the world. Harvey had the ability to inspire you. He gave voice to our rage and to our hopes. [Milk’s murder] was a devastating moment; we had lost a great leader. But in a way it also prepared us for the difficult times to come, where many of us would lose so many friends to AIDS.

Allan Baird: I lived in the Castro District; I was born there. My wife and I were friends with Harvey, my mother-in-law was friends with him. He was the type of person who would walk down Castro Street and talk to everyone. He was not just for the gay people, he was for the so-called straight people. He liked to say to me, “Allan, I’m a queer.” I never liked the word myself, but he was so proud of his being gay, that’s what he expressed himself as.

Frank Robinson: He was probably one of the most charismatic people I’ve ever met. He was very comfortable in his own skin. He saw coming out as a political tool, and used it.

Danny Nicoletta: I was 19 when I moved to the Castro. I was making Super 8 films, so to process the film I popped into Castro Camera. I was very surprised by how friendly the two guys – Harvey Milk and Scott Smith – that ran it were, especially Harvey. At that time, I didn’t quite understand “cruising,” but I appreciated the attention.

We became friends; we would talk about his New York theater days a lot. When I worked on a show called Broken Dishes, doing film and slides behind these two women onstage, Harvey and Scott came to our opening night. Harvey presented me with a little box of broken china – “break a dish,” instead of “break a leg.” He was fond of gift-giving.

Tom Ammiano: One time he came to a gay teachers meeting – he was always supportive – and there was a very handsome guy there from another county. Harvey gave a great speech, and he also went home with that guy. That ticked everybody off, because they wanted that guy.

Jason Daniels [longtime Bay Area resident]: He allowed people to have a sense of freedom; that we could talk more, that we could be more open about things than in the past. After he got elected, everyone felt more free and more powerful and safer. He put across a presence to the entire Bay Area that was quite different. It was not so much that you could be like him, but you could look to him.

Frank Robinson: I had been involved in gay liberation and politics in Chicago, but when I came to Frisco I didn’t know anybody. I was working on The Glass Inferno up on Red Rock Way, and I used to walk down to the Castro for breakfast. Harvey’s dog Kid would hump everything that passed by, and Harvey came out of his shop and I started talking to him. He asked me what I did, and I asked him what he did; “I’m a writer,” I told him. Harvey said, “I’m running for public office; how would you like to write for me? It’ll really stir some s-t and it’ll be a hoot.” All I can say is, we stirred some s-t and it took 35 years for it to become a hoot.

Gilbert Baker: [The Rainbow Flag came about when Harvey] called me up and said, “Gilbert, we need a logo.” This was when everybody had graphics, like AT & T. It was after the Bicentennial, and I had begun to notice the American flag in a way I hadn’t before. As a drag queen scene master, I thought, “We should have a flag. We’re a global tribe, and flags are torn from the soul of the people.”

Harvey loved art and creativity, which is why so many of his friends were photographers and artists. I hit on the rainbow; Harvey thought it was genius. The first day that we raised the flag, he said to me, “This will be the most important thing that you ever do in your life.” People look at that flag now, and feel ownership of it.

Anne Kronenberg: I had lived in the Castro for years but put Harvey on a pedestal, so I didn’t really know him. When I went to work with Harvey, the first thing he said to me was, “I yell a lot, I’m very vocal. You have to learn how to yell back,” because I was pretty quiet. He said, “You have to yell back at me and you can’t take anything I say personally, because it’s just the way I express myself.” So we would have some good shouting matches. Harvey was not a swearer at all, I’ve always had a pretty foul mouth. Everyone at Castro Camera liked that I could dish it right back when they dished it out to me. We became a family, and I had to keep the boys in line and on schedule. In the shop, at campaign headquarters, we had kids, seniors, straights, gays – it was marvelous.

Harvey was his own campaign manager, not me. He understood that, if he was going to win the campaign for supervisor, he needed to have women by his side. But long before I met him, Harvey was speaking out for women’s rights, for the Equal Rights Amendment. Everything that I ever learned about politics I learned from Harvey. He was brilliant, and had the best sense of humor.

Michael Wong: Harvey had a great sense of humor, and I think it covered up a lot of sadness in his life. When Jack Lira died, I called him. It was the first time that he and I had ever spoken intimately about personal things. I realized that he was not a very happy person. I think that’s why politics were so important to him; it gave him a venue to be happy and to do things that he wanted to be able to do to help others.

Danny Nicoletta: There was a community forum called Together, over at Collingwood Hall, in response to the police arresting guys for loitering on Castro Street after the bars closed. Harvey and Scott spoke, and the veins were popping out of their necks. That was my first exposure to Harvey’s oratory capabilities. Over the years, I saw him hone it to a fine art.

Carol Ruth Silver: He was very articulate, but he had a New York accent that he never tried to soften. He was a little bit choppier in his way of speaking than somebody who was perhaps more professionally trained in public speaking. But he would always punctuate his speeches with hand motions, which made him a very effective speaker.

Frank Robinson: There were two kinds of speeches that Harvey would deliver; one, more stiff and formal, before a commercial group, a meeting of shopkeepers or something like that; and a second, when addressing a crowd. For those, he would go through what I’d written and cut down the length of the sentences. He picked up on what African-American preachers would do; repetition, short sentences, pumping the air. Then the crowd would pick it up as a chant, which is of course what they’re supposed to do. Before a crowd, there was no one better; he would tailor a speech depending on who he was speaking to.

When he came to town, there were a lot of gays living in town, but there was not a gay community per se. Gays in town would elect “friends of the community” who would be your friends until you came to a rock and a hard place, and then they didn’t know you. Harvey’s idea was that you had to elect a gay man because you knew he wouldn’t change, and that he would be there. He would go the gay bars while campaigning because that’s where the people were, and he would urge them to come to the camera store and register to vote. A few years later, when AIDS hit, there was no support from the government or the state; there was support from the city and from the gay organizations that had grown up when Harvey was running and then finally became supervisor.

Tom Ammiano: You felt that you could have representation through this guy. One of the big issues then was the cops at Mission Station. Harvey recognized that there was a connection between what they were doing to do gay people and what they were doing to black people. I loved seeing him on the corner of Castro and 18th; the bars would have closed, and there would be all these queens around him and two cops, and he would be talking to the cops; “Why are you here? We’re not a violent crowd.” Because the cops would sometimes wait outside of gay bars until everyone was out around 2 or 3 AM and shake them down. Things have much improved since then.

Danny Nicoletta: After Harvey won, same-sex lovers were able to walk down the street hand in hand and not be harassed. That’s why so many people came, and come, to San Francisco.

Carol Ruth Silver: By the time the San Francisco gay rights ordinance legislation came before the Board of Supervisors, Harvey and I had left nothing to chance; we had talked to every member of the board and knew what everybody was going to vote. When we walked into the chamber that day, we knew we had the votes and that something historic was going to happen.

Frank Robinson: Probably the single most important thing for any political leader is personal courage. When he debated John Briggs going up and down the state – that was personal courage to the ‘nads. He was afraid he would get shot, because there was enough emotion out there. To the best of my knowledge, he was the only politician in the entire state who was willing to take on Briggs one-on-one.

Tom Ammiano: Once you’re self-affirmed, which Harvey was, it was mutual; crowds would feed off of him and he would feed off of them. The Chinese supported him. He was very accessible to the African-American community. You would walk down Castro Street and see Harvey meandering up and down, talking to people. You had a sense that he was comfortable in his own skin and with other people, and we needed that at the time. He also had that New York élan which people responded to; always a little bit bemused and extremely empathetic.

Frank Robinson: He was the last of the storefront politicians, the last guy to run for public office out of a little store that he owned and managed on a public street, and with no money. He loved being on the campaign trail. We would be in the middle of a campaign, scrambling to get money and stuffing envelopes. He would come in from the campaign trail would tell us about two little old ladies that he’d met and that were going to vote for him. He could have his depressed moods, but not on the campaign trail.

Allan Baird: In 1973, I went in and met with Harvey, and explained to him who I was directing the Coors boycott. I told him that I needed the support from the gay community, and this beer taken out of all gay establishments. He was easy to talk to; no bulls-t, straightforward in everything.

He said, “Okay, Allan, I’ll do it but I need one thing from you.” I said, “What do you need?” He said, “I want you to start dispatching open gays into Teamsters Union driving jobs. Do you agree?” And I shook hands with him and said, “Yes, I do agree. And we will do it.” He jumped up out of his lounge chair and started yelling at everyone in his store – there were people hanging around all the time; “Look, get Coors Beer out of every gay and straight establishment. Not only gay, gay and straight; I want it removed immediately.”

The next day, three guys showed up and said they were gay and that Harvey Milk sent them to be Teamsters Union drivers. I dispatched them in, one by one. The first person that was hired was a man by the name of Howard Wallace, who is very active now in the San Francisco gay community. I believe we were the first union in the United States to endorse an openly gay person, Harvey, for public office.

Cleve Jones: Today, hundreds of openly gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people serve in elected offices across the country, in almost every state. They bring real leadership, not just for the gay community but for entire communities. Harvey paved the way for that. He showed us what was possible. By his example, other people saw that by being fearless and crossing all of these boundaries that divide us, amazing things can be achieved.

Danny Nicoletta: Cleve and I have both been able to evolve with our natural propensities; mine being creative work and his being politics – which is not to say politics is not creative, or vice versa. In fact, that was one of the great lessons of Harvey’s; those two worlds can and should work together.

Tom Ammiano: I said to Harvey once, “Why the hell do you want to run for office? We accomplish so much through civil disobedience and picketing.” He said, “You know, I like both things.” That was a lesson for me later when I ran for office; his message was, remain an activist and still be an elected official. He brought heart to politics, but was smart and could be calculating.

Anne Kronenberg: His timing was so good. He knew how to, and when he had to, get his point across with the media; he knew where the hook was. He always could figure that out in a way that I don’t think many people have the talent to.

Charles Leavitt [former SF resident]: He showed a lot of people that he was a gay man who did not fit the stereotype. You think of Harvey as a rebel, but he was really someone who believed in the system. He was a politician who played the game. Tragically, what he could have done was cut short.

Michael Wong: The turning point in Harvey’s political life was the State Assembly election in 1976. It was him versus the machine; [winning candidate] Art Agnos had the support of Governor Jerry Brown, the labor unions, and the entire Democratic establishment. He realized that if he was going to win, it would not be with the backing of powerful politicians. After he won, he reconciled with all of them and they became powerful allies.

So there are the lessons; first, never give up. Second, don’t be a spoiled winner; when you win, reach out to the people that didn’t support you. The other lesson is, he wanted young people to not to despair.

Danny Nicoletta: Harvey very much spoke to youth culture and really wanted them to be engaged, not despondent and apathetic. At the very least, vote, please vote. It doesn’t matter what side of the fence you fall on. In fact, just tear the fence down; we all live in the same world.

Cleve Jones: I’ve worked with a lot of political leaders in my life, but I’ve never met anyone who had as much genuine empathy as Harvey Milk. He was able to connect with anybody, really – homeless people, rich people, firefighters, left-wingers… The basis of his strength and the source of his power was that when you spoke with Harvey, you knew he wasn’t putting on the right facial expression or making the necessary eye contact, he was getting it.

Here was a man who came from the really bad old days; he formed his sexual and political identity during the height of the Holocaust. He moved past despair and cynicism and reached out with courage.

Background: Timeline

1930 May 22 – Harvey Bernard Milk is born in Woodmere, NY

1946 Milk makes the Bay Shore [, NY] High School junior varsity football team

1947 Milk graduates from Bay Shore HS

1951 Milk graduates from State University (SUNY) Mathematics, and joins the U.S. Navy at Albany with a degree in

1955 Milk is honorably discharged from the U.S. Navy and pursues a career as a high school teacher

1963 Milk begins a new career with the Wall Street investment firm Bache & Co.

1968 After dabbling in off-Broadway theater production, Milk moves to San Francisco with his lover Jack McKinley, who is working on that city’s original staging of the musical Hair; in SF, Milk gets a job in finance

1969 June 28 – The Stonewall Riots in New York City’s Greenwich Village spark the birth of the Gay Liberation movement

1970 After publicly burning his BankAmericard, Milk is fired from his job; he moves back to New York City

1972 Milk moves from New York City back to San Francisco with his lover Scott Smith

1973 Milk and Smith open the Castro Camera shop in the Castro District

Allied with Teamsters representative Allan Baird, Milk effects a ban of Coors Beer from bars in the Castro District and elsewhere in the city

[during this timeline through 1978] Dick Pabich and Jim Rivaldo work with Milk as political strategists; Frank Robinson works as Milk’s speechwriter

With a campaign managed by Smith and Rivaldo, Milk runs for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors for the first time, and loses

1974 Milk reorganizes the Castro Village Association of local merchants, and helps launch the first Castro Street Fair

[during this timeline through 1978] Michael Wong works with Milk advisor as an

David Goodstein becomes owner and publisher of the national gay magazine The Advocate

1975 Castro Camera customer Danny Nicoletta joins the shop’s staff, in addition to working on all of Milk’s subsequent campaigns

Milk again runs for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and loses; former California State Senator George Moscone, supported by Milk, is elected Mayor of San Francisco

1976 [during this timeline through 1978] Cleve Jones works with Milk as an activist

Milk is appointed by Mayor Moscone to the Board of Permit Appeals, a position from which he is later removed by the mayor after announcing a bid for California State Assembly

Milk is instrumental in placing a ballot initiative approved by Mayor Moscone that successfully replaces citywide elections with district elections

Milk loses the State Assembly election to Art Agnos

Milk and Rivaldo co-found SF’s Gay Democratic Club (which is posthumously renamed the Harvey Milk Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender Democratic Club)

1977 June 7 – “Orange Tuesday;” Activist Anita Bryant wins her campaign to overturn Dade County Florida’s gay rights ordinance, effectively mobilizing a decades-long campaign of intolerance against the gay community

With the new district elections system in place, Milk – now living with his lover Jack Lira – runs for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors for a third time in a campaign managed by Anne Kronenberg, winning the seat for District 5, which includes the Castro; he is the first openly gay man ever elected to major public office in America (following the 1974 elections of openly gay women Kathy Kozachenko and Elaine Noble in Michigan and Massachusetts, respectively); among his opponents in the election is openly gay attorney Rick Stokes

1978 January 9 -Milk is sworn into office, as are his fellow newly elected supervisors ex-fireman Dan White (representing District 8, the Excelsior District) and women’s rights advocate Carol Ruth Silver, among others

Issues that Milk acts on while in office include programs for senior citizens; dog owners cleaning up after their pets; and accessible and comprehensible voting machines for all citizens

With schoolteacher Tom Ammiano coming out and putting a face on the issue, Milk captains the landmark San Francisco gay rights ordinance (he notes that the ordinance’s “main focus is to prevent people from being fired”), which is co-sponsored by Silver and passed by the Board of Supervisors (White’s is the only dissenting vote); Mayor Moscone signs the bill into law