Taglines: All that stands between light and darkness is the night watch.

Night Watch movie storyline. From Russia, with horror, comes the stylish fantasy horror film that has revolutionized post-Soviet cinema: Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor). The film brings to the fore the cutting-edge vision of director/writer Timur Bekmambetov (whom Russian director Nikita Mikhalkov called “our Tarantino”) and is the first instalment of a trilogy based on the best-selling Russian sci-fi novels of Sergei Lukyanenko (which also include Day Watch and Dusk Watch).

Featuring a dazzling mix of state-of-the-art visual effects, adrenaline-fuelled action sequences and nail-biting terror, Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) was an instant smash hit in its native Russia when it was released in July 2004 shattering all previous box office records.

Made for a mere $4 million, the film surpassed both Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King and Spider-Man 2 at the Russian box office. In a country that had not seen a native film make more than $2 million, Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) went on to gross eight times that number. Internationally acclaimed, it was also Russia’s contender for the 2004 foreign language Oscar.

Set in contemporary Moscow, Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) uncovers the other-world battle that upholds a 1000-year-old truce between the forces of Light and the forces of Darkness. For centuries, the undercover members of the Night Watch have policed the world’s Dark Ones –the vampires, witches, shape-shifters and sorcerers that wage treachery in the night — while the Dark Ones have a Day Watch that in turn polices the forces of Light. The fate of humanity rests in this delicate balance between good and evil but that fate is in jeopardy…

Inside the Night Watch: About the Film’s Origins

Sergei Lukyanenko’s novel Night Watch — and its sequels Day Watch and Dusk Watch — marked a watershed in Russian literature. The book’s story of supernatural battles breaking out on the frenetic, everyday streets of modern Moscow struck a resonant chord with a whole new crowd — young Russian readers, fantasy fans and Internet users — who turned them into instant hip, cult classics, selling 500,000 copies. Since the Russian release of the feature film of Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor), the trilogy has gone on to sell another 2.5 million copies.

A prolific author who was originally trained as a psychiatrist, Sergei Lukyanenko had always wanted to write an epic tale of ancient magic set loose in our modern times. “I’d been eager to write fantasy for quite some time, but neither gnomes nor elves were of any interest to me,” explains Lukyanenko whose other books include the trilogy Line Of Reveries and Knights Of The Forty Islands. “Then, I had an intriguing notion: this idea of the Night as a battlefield for magicians who live in hiding among us ordinary people and can only fight when it won’t disturb humanity. From this came the further idea of the Night Watch, a special unit created to control the magicians. This then led to the development of the Night Watch’s antagonist, the Day Watch, and their eternal battle against one another.”

Soon, the supernatural beings who run the Night Watch and the Day Watch – beings with devastating magical powers who operate just one step away from the normal urban reality of rundown apartments and crowded subways — were captivating readers across the nation. Among those readers was leading Russian film producer Konstantin Ernst, who is also the General Director of Channel One Russia, Russia’s biggest and most successful television network. Ernst wasn’t usually drawn to works of fantasy, but when he picked up Night Watch, he found that he couldn’t put it down. Now, fuelled by a passionate enthusiasm for the story’s cinematic possibilities, he immediately dove into development, along with fellow producer Anatoly Maximov. Nine months later, shooting began with a screenplay adapted by Lukyanenko himself in collaboration with Timur Bekmambetov.

To direct Lukyanenko’s tale of witches, warlocks and vampires set loose on city streets, the producers knew they would need a true visual innovator. They started looking for someone with a distinct and original sense of both story and style – and someone who could combine the powerhouse thrills of modern specialeffects filmmaking with a personal understanding of the Russian soul.

They found what they were looking for in Kazakhstan-born Timur Bekmambetov, an acclaimed creative powerhouse in the fields of commercials and music videos, who has helmed more than 600 ads for brands including Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Apple, Microsoft, Ford and Procter & Gamble. Bekmambetov made his feature film directing debut in 1994 with The Peshavar Waltz, an art-house film about the war in Afghanistan, and his second film,Gladiatrix (2000) (also known as The Arena), was filmed in English and co-produced by the legendary Roger Corman.

“Timur is highly visual,” says producer Anatoly Maximov, “and he also goes very deep with the characters, in a Stanislavski way. It’s from this combination that the film’s style was born.” Konstantin Ernst first met Bekmambetov when the former was the host, producer and director of a Russian monthly arts and culture TV show called “Matador.” The two men often shared an editing suite and discussed making movies together.

“One of my biggest aims has always been to recreate the Russian film industry, and we talked about that,” explains Ernst. “I explained to him that I wanted to forge a new image and get to a new level in Russian movie making that would make it a real part of the international movie arena — not just for art-houses or for festivals, but with exciting films that appeal to a mass audience. With Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor), we had that opportunity.”

Bekmambetov brought to the project a deep personal love of modern Hollywood masters of action, counting among his major influences such filmmakers as James Cameron, Ridley Scott, Roger Corman, the Wachowski brothers and Quentin Tarantino. Still, he was initially skeptical about creating a fantasy horror that would appeal to Russian audiences.

“Unlike in America, there were no fantasy movies shot in Russia before this one,” the director points out. “But in reading the book, I suddenly realized Sergei had managed to distill magic and miracles, the transcendent and the supernatural, into our way of life. I found that the story really was something special because in it, fantasy not only meets reality – but Russian reality — and it’s the first Russian movie that has this unique point of view. The story takes place in the real world, in real Russian life, but it’s also fantastical. So my idea was to make it feel as real as possible on the screen, while also finding a context for the mystical and the fantastic in contemporary Moscow life. It was a wonderful challenge.”

The more he read, the more Bekmambetov was hooked on the vision of vampires roaming the often chaotic and troubled streets of current-day Moscow. “The books became poetry. They were cool. They were funny,” he says. “It woke me up because I started to think about how you could connect these things: Red Square and vampires, vampires and the Russian ballet, etcetera. It was such an interesting mix and I found that it produced in me a very personal feeling because one half of me is the filmmaker who loves vampires, Roger Corman and The Matrix. Meanwhile, the other half of my mentality is a Russian reality where there are lots of problems – where there are very bad cars, very dirty houses, very rich oil barons and very poor people. This story brought these two sides of me together: Russian reality and American movies.”

Bekmambetov began to see the film as a way to mesh all his influences together into one original entertainment – and he peppered the film not only with wild chases, hair-raising stunts, powerful explosions and other-worldly creature effects but also with that particular mix of sly humor, rich philosophy and human insight that has always marked Russian literature.

He was especially drawn to the story’s allegorical exploration of the fragile balance between good and evil in the world today. For Bekmambetov, the members of Night Watch and their opposite members in the Day Watch represent two different, competing social philosophies. “They represent two different ways to live – total freedom versus responsibility,” he comments. “The Day Watch are the Dark Ones and they represent a kind of totally free independence, but the Night Watchers are all about responsibility and conscience. It’s a dualism that’s existed for a thousand years. It’s a very old idea that you must consider the consequences of your actions.”

Bekmambetov worked closely with Lukyanenko to adapt the novel to the screen – and found Lukyanenko more than willing to play with his creation, even adding in new elements to heighten the moviegoer’s experience. “We added in the subplot of Anton (Konstantin Khabensky) and his long-lost son Yegor (Dima Martynov) to make it more dramatic, more emotional, more Russian,” explains Bekmambetov. “On top of the action, you have this tale of a father who lost his son, feels terribly guilty, and then spends his life trying to solve this problem that is plaguing his conscience — it’s a very Russian story.”

In preparing to shoot the epic story on a far less-than-epic budget, Bekmambetov always kept in mind what his friend and mentor Roger Corman once told him was a vital lesson in filmmaking. “He said the most important thing for the director is to think about how to imitate a bigger budget than he has,” Bekmambetov recalls. “It’s all about creativity.”

Key to Bekmambetov’s creative vision of the film was an omnipresent and intense realism laid over the pervasive and inventive special effects. Indeed, the director says he wanted the film’s hair-raising vampires, witches and warlocks to seem at once menacing… yet as real as a person’s next-door neighbor.

“Russian audiences don’t have any experience of this kind of film, because we’ve never had any fantasy movies or comic books — it’s all new. So the only way for me to begin was to make everything very realistic, so the audience would believe in it enough to accept the fantasy,” he explains. “For me, this meant I too had to believe in a world where vampires exist, even if I know that they don’t.”

For Anatoly Maximov, Bekmembatov’s approach brought to the film an undercurrent of relevance that made it even more exciting. “The world he creates is hyper-realistic but recognizable,” he says. “The characters, the social situations and the psychological elements are all familiar to us. It becomes a movie about a man’s moral breakdown and the forces of Light and Darkness fighting for his soul — it’s big stuff.”

Creating the Night Watch

A large part of the thrill of Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) is its extraordinary visual energy – as it creates a fully-realized fantastical universe on the scale of a STAR WARS or MATRIX, while also providing a rare, eye-opening glimpse of modern-day Moscow. The world of Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) is one in which a dilapidated old flat might be a hiding place for vampires and an ordinary Moscow repairman might turn out to be an undercover magician.

For director Timur Bekmambetov, the sharp, eerie, visceral look and feel of the film was always a key priority. Having studied theatre and cinema design at the Tashkent Institute of Theatre Arts, Bekmambetov adopts a hands-on approach to every physical detail of his films. “I’m an artist,” he says. “I spent eight years studying drawing and it’s what I like to do.”

His vision for Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) began with the idea of creating a mythology around the declining state of Russian cars, furniture and homes in the post-Soviet era. “We wanted to create a mythology around these Russian items and make everything that was considered ugly and unfashionable become part of a magical world,” he explains. “Russian people tend to be ashamed of their belongings, of their simple, very old chairs, or their loud and bad cars; and their buildings that are dirty tower blocks. We felt that it was sad because nobody knows what’s good or what’s bad. So we created stories around why an old chair might be the best, or why this old car is so tough and cool. And it seems to have had an impact.”

Indeed, the film’s world quickly began seeping into Russian popular culture. Lines of dialogue from the film have entered the Russian lexicon while Anton’s long coat has become a hot clothing item among certain Moscow youths. “The costume of the Night Watchers, this big coat especially, is very fashionable,” notes Bekmambetov. “It’s become a kind of fashion cult.”

Bekmambetov also wanted to inject a dose of visual caffeine into the arm of Russian cinema with Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor). Rather than the slow and leisurely pace favored in the years of state-sponsored filmmaking, Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) introduces break-neck speed, lightning-quick film cuts and hyper-kinetic cinematography to Russian movies – and there may be no turning back.

“Young people like this language, they like the energy of music videos and the clarity of commercials,” comments the director. “They like the speed of the story, they like the action fast and dramatic. And we choose this style because we felt it would speak to our audience, and, of course, because we as filmmakers like it as well.”

Within this visually dazzling universe, Bekmambetov also hoped to present a picture of Moscow that has never before been seen by much of the world – that of a vibrant, youthful, active city. “The typical image of Moscow is of a very grey, depressing city,” he explains. “Our idea was to make a movie that changed that image to something much more fun and cool and happening. Over the last two centuries the government has altered the image of the Russian soul and made everything grey and white but originally Russian culture was very colourful, very emotional, very dramatic, and we decided to go there, to go back to this type of visual intensity. So in our filmmaking and our color correction, we emphasized making Moscow filled with bright splashes of color, almost as if it was Mexico.”

Bekmambetov filmed all of Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) and 80 per cent of its sequel in 90 days at the tail end of 2002 and the beginning of 2003. The production shot in more than 200 authentic Moscow locations, including the world-famous tourist locale of Moscow’s Red Square, as well as the city’s expansive, underground Metro system. Most of the action is centered in and around the Ostankino Tower, the city’s soaring communications tower that stands over the north-west sector of the Russian capital, a focal point of both the city and the story.

“Much of the original novel takes place around Ostankino Tower, so it was important for us to shoot there,” Bekmambetov explains. “In Russian, Ostankino is a very mystical name. It means ‘remnants,’ and there are a lot of mystical explanations why Sergei set his book there. But there is a practical one too. He’s not from Moscow — he came from Kazakhstan — and Ostankino became the one place he always knew, a center-point for locating everything.”

Bekmambetov was keen to shoot as much as possible on the streets of Moscow, capturing a raw reality behind the chills of his supernatural thriller. “It was essential that the film show real images of contemporary Russia,” he notes. “We present very real images, but with a little bit of a twist, heightening the immediacy with the photography, because we wanted every Russian viewer to think, ‘that’s my house,’ ‘that’s my street,’’ it’s not artificial, it’s real life.’ It’s one of the tricks of the film and one of the hooks of its success. Only the apartment interiors were sets — but even with these, we had a very good art director and he created highly realistic homes, with a lot of detail. They even smelt real.”

In bringing to life the world of Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor), Bekmambetov called upon an artistic crew that he has worked with on his previous two films as well as numerous commercials over the last decade. “I have a very good team that I have collaborated with for maybe 10 years,” comments the director. “This includes director of photography Sergei Trofimov and art director Valery Victorov, who is also my girlfriend. Valery was the creative producer overseeing the film’s entire style — from the sets to the costumes to make-up. Together, we developed this idea that every element in the film has to feel real – but with a surreal context.”

To this end, the director also searched for locales that would inspire primal reactions of fear and anxiety. “We started looking at all the mystical and scary places we have around us,” he says. “For me, ever since I was a kid, I have always felt the roofs of Russian buildings are very scary places because they’re usually very high and full of antennas that look just like spiders. The Metro is also a mystical place in Moscow, perhaps because Stalin built it. We also used a particular Metro station in the movie that is named XXX and since school days, I’ve always felt this name looks like something evil.”

Bekmambetov even set one of the film’s early spectacular battle sequences between Anton and two vampires in an abandoned barbershop, simply because it seemed so odd and discomfiting. “There is something very personal, very subliminally frightening about the barbershop,” he notes.

Finally, one of the most arresting sights in Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) is that of The Gloom, the eerie netherworld that only The Dark Ones and The Light One – known as The Others — can inhabit. “The Gloom is a kind of parallel world where The Others can meet each other and fight each other,” explains Bekmambetov. “It’s understood if you are in the Gloom, you must be an Other, because there are no human beings in The Gloom. This also meant we could venture far outside reality to come up with the look.” There is, however, one lingering touch of realism in The Gloom – the place is buzzing with mosquitoes. “There are a lot of mosquitoes in The Gloom because it’s my personal phobia,” Bekmambetov laughs. “I’m scared of mosquitoes.”

Beyond the Night Watch

In Russia, Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) became not only an entertainment phenomenon but a sign that a new, revitalized, post-Soviet Russian cinema had finally arrived to save the crumbling film business. Previously, in the days of the Soviet Bloc, Russian cinema was a strictly controlled, government-run industry turning out around 200 films each year for its captive audience. Though the Soviet Union produced a number of legendary directors in the modern era — including Andrei Tarkovsky, an influence on Timur Bekmambetov, and director of such films as Solyaris, Andrey Rublyov and The Mirror – the system largely curtailed freedom of expression.

After the fall of the Communist regime, and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russian cinema suffered further. Instead of experiencing a rebirth, it went into a severe decline for more than a decade — with movie screens around the country being cut in number from around 10,000 to a scarce 70. “The theatrical system was absolutely destroyed,” says producer Konstantin Ernst of that era, “and meanwhile, there was a huge growth of piracy which further decimated the industry.”

Only in the last three or four years has the situation begun to improve, helped by the advent of new, high-tech movie theatres and a much improved distribution system that has allowed cinemas to compete with the booming numbers of television stations. Now there are about 1,000 movie screens in Russia catering to a younger, more enthusiastic audience.

“Today Russia has 20 very good, modern TV channels and that has changed the market for entertainment,” explains Ernst. “In the last three or four years young Russian people have started to understand there is a difference between seeing a movie on TV and seeing it in the theatre, and the theatrical audience is now growing.”

Continues Ernst: “We have learned that this new Russian audience is not the same as 10 years ago. Instead, it’s made up of young people, aged from 14 to 25, who didn’t have the Soviet experience. This new generation of filmgoers are used to seeing big, thrilling Hollywood blockbusters. So we knew that to really reach them we would need to use the language of American movies – but reinvented in our own way.”

It was this audience that Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) helped at last to capture. Yet Ernst stresses that Night Watch (Nochnoi Dozor) was never intended to simply be a Russian imitation of a Hollywood fantasy-adventure blockbuster. Rather, he sees it as a new type of Russian movie that takes off from Hollywood conventions to become its own unique kind of movie experience.

“Timur and I are of course great fans of American film, but for us it was very important that Night Watch be a Russian movie, and we believe that this was the key that led to the box office success we had with Russian audiences,” Ernst says. “This film was seen as being like Tarkovsky meets the Wachowski brothers – a new image for Russian movies that excited people.

Night Watch (2006)

Nochnoy Dozor

Directed by: Timur Bekmambetov

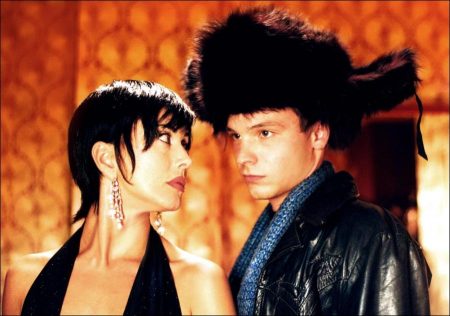

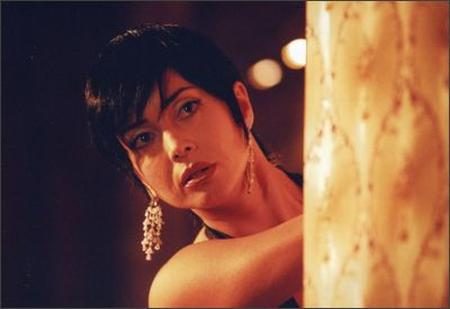

Starring: Konstantin Khabensky, Vladimir Menshov, Galina Tyunina, Mariya Poroshina, Viktor Verzhbitskiy, Ilya Lagutenko, Mariya Mironova, Dmitriy Martynov, Anna Dubrovskaya

Screenplay by: Sergei Lukyanenko, Timour Bekmambetov

Production Design by: Mukhtar Mirzakeyev, Valeriy Viktorov

Cinematography by: Sergey Trofimov

Film Editing by: Dmitriy Kiselev

Costume Design by: Varvara Avdyushko

Art Direction by: Valeriy Viktorov

Music by: Yuriy Poteenko

MPAA Rating: R for strong violence, disturbing images and language.

Distributed by: Fox Searchlight Pictures

Release Date: February 17, 2006

Views: 90