“Shall We Dance is not just about a restless man entering the seductive world of dance,” says director Peter Chelsom, “but about a whole group of people who through a kind of boot camp for dancers, get to explore who they really are and who they want to be. From the start of rehearsals I wanted us to acknowledge that the film should not be a story then a dance number, then more story and so on, but that the story always continued through the dance scenes and most importantly the story was actually furthered by the dancing.”

In 1996, the original Shall We Dance (“Dansu Wo Shimasho Ka”), written and directed by Masayuki Suo, won the hearts of Japanese audiences with its story about an ordinary, hardworking Japanese salary man who, overcome by the feeling that something’s missing in his life and marriage, learns to ballroom dance on the sly. Soon, he has transformed from a wooden, melancholy recluse into someone touched by a sense of magic and possibility. Filled with comic characters and rousing dance sequences, the film touched a universal chord in anyone who had ever longed for something a little more. It went on to win an astonishing 13 Japanese Academy Awards, and travel the globe, becoming a hit with foreign film audiences across the United States and Europe.

Among those deeply touched by the original film was screenwriter Audrey Wells, who felt the delightful story deserved an even wider audience. Wells has long had a fascination with how people are able to find passion – whether romantic or creative – in the midst of today’s busy and distracted modern lives. She’s explored this theme in several films she’s written and directed including “Under the Tuscan Sun” and the award-winning “Guinevere.” But this story was different, she felt, because it wasn’t so much about finding conventional love, but more about rediscovering the joy of pursuing one’s most hidden dreams, and about reviving the spark and passion of a good but routine marriage in mid-life.

Wells began to adapt Shall We Dance into an English-language film, but right away she realized much more than the language was going to have to change. The whole culture surrounding the story would become entirely new. In transferring the story’s location to the United States – with its far more open and diverse, yet often equally adrift, society – Wells also shifted the humor to a hipper, more American style; added Chicago color to the dance school’s comic-tinged patrons; and most of all, re-imagined the main character’s struggle. For John Clark isn’t caught up in the rigidity of Japanese society as in the original — but in his own limited definition of who he can be beyond a father and lawyer. Wells created Clark as a typical American urban professional, “the type who can do everything extremely well but doesn’t remember how to dream, until he enters that studio.”

That same rediscovery of how to dream spreads out through the rest of the characters in Shall We Dance as well, from Jennifer Lopez’s disillusioned champion dancer, who recovers her desire to compete again, to Stanley Tucci’s outrageous, disguised ballroom wanna-be, who finally learns how to be himself.

The one thing that didn’t change, however, that couldn’t change, was the script’s focus on the sheer thrills of flying around the room, ballroom style, in the arms of a partner who knows your every move. Although the story has a different tone and feel, Wells keeps dance at the heart of the story, letting the gestures and moves of John Clark and his new friends tell part of the tale, and reveal the kind of ineffable feelings that go beyond language.

The combination of buoyant dance sequences, spirited comedy and a moving storyline about contemporary lives compelled producer Simon Fields and director Peter Chelsom to immediately want to make the film as soon as Wells’ script arrived at their office. They felt this new version of Shall We Dance not only held out the promise of great fun, but hit upon themes not often seen at the movies.

“This is a story people can relate to,” explains Fields. “It isn’t about a desperate man who unrealistically turns his life completely around. Instead, it’s a story about a man who, like most of us, who is basically doing really well, who has a good job, a loving family and a successful marriage. But then one day he sees this amazing face through a window and he begins to wonder if there’s somewhere higher he can go. I hadn’t read anything like that before, that touched upon this question of what’s really possible in an already pretty good life, and that was exciting. I also loved how the story juxtaposes the elegance and grace of ballroom dance against the normal routines of Chicago suburban life.”

Adds Chelsom: “What I liked about Audrey Well’ take on Shall We Dance is that these people go to miss Mitzi’s expecting to learn to dance and yet emerge learning so much more. Each character is broken down. Each character seems to be carrying a secret they are not ready to share. And they all develop because one man one day got off a train in order to have one dance with one girl he saw at a window. I like the cause and effect of the premise.”

Fields and Chelsom were familiar with the original Japanese film but were impressed by how Wells had carefully relocated it across the Pacific ocean, allowing it to reflect a more American exuberance and perspective on seeking satisfaction beyond work and family life.

Observes Chelsom: “Much of the conflict in the original Japanese film stems from Japanese taboos about the public intimacy of dance. Obviously, this wouldn’t work in an American setting. But the American taboo that’s central in Audrey’s screenplay is this idea that if you’re living the American dream, then you don’t have the right to hold up your hand and say ‘hey, I’m unhappy.’ What I loved about this story, and what I was so drawn to, is that it’s about a restlessness that is all around us but not often talked about. In spite of having so much, John Clark is missing something. It’s as if he’s living an ideal, not really living his life. He realizes that even though he and his wife are always on the move, something inside them has just stopped, and he’s driven to find some kind of passion. That’s the beautiful subtlety of this movie for me.”

Chelsom was also compelled by the chance to capture the kinetic magic of ballroom dance on film as a director. As it turns out, Chelsom hails from Blackpool, England, the acknowledged Mecca of ballroom dancing and the annual site of its World Championship. Although Chelsom himself never danced professionally, no one escapes Blackpool without an undying appreciation for the infectious joy of waltzes, rumbas and foxtrots. Explains Chelsom: “Pretty much everyone in Blackpool has been sent to dancing lessons by age nine.”

Fields, too, as a fellow Englishman, had fallen under the spell of ballroom dance as a child. He explains: “In England, ballroom dancing is very much a part of our culture, and is actually considered a big sport. When Peter Chelsom and I were growing up, every Sunday we had two hours of ballroom dancing on television. So to take on a film that is about the allure of dancing seemed, for us, almost second nature.”

Surging in popularity in the U.S., ballroom is a uniquely transporting dance style – featuring a man and a woman gliding across a bare floor responding only to the music and one another. Each individual dance has its own creative personality, its own emotions and appeal to the spirit, from the raw eroticism of the rumba to the intimate charm of the waltz. With its inherent fluidity and romance, ballroom dancing is also a highly cinematic art-form, as Chelsom discovered as he set out to reveal its tenderness, its exhilaration and some of the suspense of dance competitions on screen.

“I’ve always felt that Ballroom is secuctive and a little ridiculous at the same time and that makes for great comedy. It also makes for moments of extraordinary grace. It takes courage – especially if you’re John Clarke. It’s actually not about the dancing, it’s about the daring. I had been looking to make a film about dance for many years.

* * *

To play John Clark — the quiet, hard-working lawyer who gets off his train one night and steps into a life-changing desire to dance — the filmmakers knew they needed someone special. They wanted an actor so assured and charismatic that, right off the bat, most people would assume he must be happy – a significant switch from the low-key businessman of the Japanese film – and that he’s the last person on earth who would seek out dance lessons in a dilapidated studio in a gritty part of town.

“We knew we didn’t want a ‘Willy Lohman’ type or your average middle class man for John,” explains Field. “Instead, we wanted someone who already appears fulfilled, a man clearly at the top of game. Then, when he takes this left turn that re-ignites his enthusiasm and revitalizes his marriage, it takes both the audience and him by surprise.”

These criteria led the filmmakers to Richard Gere, who most recently won a Golden Globe Award for his role as the far slicker, soft-shoeing lawyer in “Chicago.” “We needed a subtle performance from someone who could also learn to become a great dancer before the audience’s eyes,” remarks Peter Chelsom. “What’s interesting about Richard’s character, John, is that he’s a guy who’s never really been the center of attention. He’s always been the one keeping things together, being the dad, the boss. But now he has all this space just to be himself, and he’s very selfconscious about it at first, until he starts to open up, which Richard captures beautifully.”

The role appealed to Gere who, like his character, was initially drawn to the alluring image of a girl staring out the window – and all the what-if’s and what-might-have-beens such an image arouses. “I felt that this was the kind of experience that everyone has had at one time or another, riding in a car, or in a plane or a train, where you suddenly see this person and you become aware of this whole other world out there that you could be a part of,” Gere says. “The interesting part is that most of us turn away, while John decides to explore it which leads to something very positive for him.”

He continues: “I don’t think in the beginning John can even pinpoint anything that is wrong in his life or marriage. It’s more of a distant dissatisfaction he can’t put his finger on. And the challenge as an actor was figuring out how to show that. Melancholy isn’t something you can play exactly – you can’t paint melancholy on a face. So I approached the feeling inside John more as a kind of itch, a kind of inner agitation he doesn’t really understand at first, that drives him to do something that seems pretty crazy in his world, but that expands his whole life in a new direction.”

Gere was also drawn to the theme of Shall We Dance, which he describes as “learning to become the person you dream of yourself being.” He especially liked the idea of joining an ensemble of actors who each discover new sides to themselves – both comic and serious — through their willingness to let it all go while they dance. “Every character at the studio has their own quirks and oddities, and Miss Mitzi’s becomes its own wonderful little world of outcasts,” comments Gere.

“But there’s also an honest camaraderie and acceptance of one another there. I think John comes to see that all the people at the studio from Paulina to Vern, once had dreams for their lives, but then they got to a point where they didn’t believe in them anymore, or life’s obstacles got in the way. In the course of the film, they all come face-to-face with their dreams again. I think, in fact, we all can.”

Though Gere is not professionally trained, ever since his tap-dancing role in “Chicago,” he has had his own love affair with dance, the freedom and fun of which he sees as a key to John Clark’s transformation. “The emotional and psychological challenges of really opening yourself up to a dancing partner, of becoming sensitive to your every move, of accessing deeper emotions to express yourself, changes you,” he comments. “That’s why we still love Fred Astaire, because his grace and his open heart still move us today. There’s just something about dancing that has that power.”

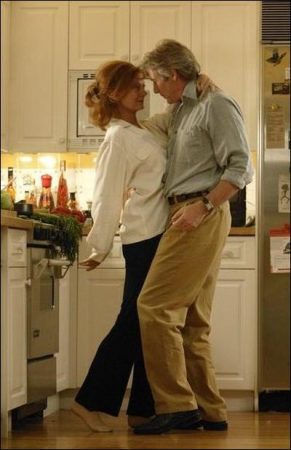

Another aspect of the film that impressed Gere was the realistic treatment of John Clark’s marriage, which is not so much troubled as it is just a little blasé after so many years of union. “It’s not the usual dysfunctional relationship,” Gere notes. “Really, I think the Clarks are typical of many American households, where nothing’s really wrong, but maybe you also have the feeling everything’s not quite as great as it could be. Susan Sarandon is wonderful as Beverly, John’s wife, because she’s so grounded and rooted and she sort of waits to see where her husband’s existential crisis is going to lead.”

The filmmakers chose Susan Sarandon for the role of Beverly because of her distinctive embodiment of feminine intelligence. Notes Chelsom: “Susan rides that fine line between revealing the depth of the film’s themes while also playing it for comedy. She really embraced the deep sorrow of being a wife who feels excluded from her husband’s life, and at the same time, she captured this funny neurosis that escalates when you start to mistrust your spouse. It’s the goodness of her character that really breaks your heart. Because she’s done nothing wrong, but she isn’t sure what to do about her husband’s restlessness. She is type of wife who really takes care of her family and so it throws her to find out what her husband wants right now is something she cannot provide.”

To play Paulina, the dance teacher who has lost her inspiration until John Clark arrives, Peter Chelsom hoped to find an alluring actress who also had a significant background in professional dance – which led him to Jennifer Lopez. Chelsom considered her life-long passion for dance an invaluable asset to the film. “We thought it was vital to have an actress who understands with her body and soul what it is to dance and to live that kind of unpredictable, emotional life,” he says. “Jennifer embodies that, and she is such a terrific dancer that you really believe she could be a ballroom champion.”

While her counterpart in the Japanese film was more fragile, the filmmakers saw that Lopez could convey the vulnerability of the role while adding her own strong personality and open sensuality. “Jennifer has the same longing as the original Japanese character but she brings something more vibrantly American and fiery to it,” says Fields.

Lopez was intrigued by the script not only because of the dancing, but because of its picture of ordinary people finding extraordinary inspiration in their lives. “I loved the portrait of these different types of people from many walks of life all coming together to fulfill some long lost dream,” she says. “The dance studio becomes a place where they can find out who they are, what they want and what’s missing from their lives. And, most of all, dance gives them a beautiful place to go, to forget about things, and just fly above it all.”

Another major influence on John Clark is Stanley Tucci in the role of Link Peterson, an office geek by day at John’s law firm who has an outrageous alter ego that emerges when he is practicing his beloved Latin dances at night. Tucci was eager to play the lively comic role that is a departure from anything he’s done before. “I love Link as a character, because to me, no one is just one person, no one is just whom they present to the public or to their family. Everyone has some secret part of themselves they they’ve always wanted to express,” he says. “To be able to play somebody who has two separate parts of himself that then merge into one whole person at the end, that is a thrill, it really is a thrill. And then there’s the fact that it’s an incredibly funny part.”

Richard Gere got his own thrill from watching Tucci bring Link to life. “Stanley has brought so much invention, creativity and courage to playing this part, it’s really something extraordinary. It reminds me of great characters Peter Sellers explored in his heyday, something really out there,” he says. “It’s not easy to be both goofy and controlled. His comedy has great verve to it, but I know the incredible skill that went into creating Link.”

Among John’s other comical fellow classmates at the dance studio is Chic, who signs up for lessons with the stated purpose of picking up women. Bobby Cannavale, who recently won acclaim in “The Station Agent,” plays the character whom he calls “a walking hormone.”

Cannavale explains: “Chic’s theory is that if he can somehow become a great dancer, he’s going to have chicks dropping all over the place for him. But the beauty of the movie is that all these people who are taking the class are really in it for another reason, and through the dance they’re able to express that. So it becomes much deeper than just about picking up girls for Chic in the end. There’s an evolution inside him and learns to express himself in a completely different way that what’s there on the surface.”

In the role of Vern, who claims he’s learning to dance for a mysterious fiancée, Chelsom and Fields cast a newcomer: Omar Miller who made his debut in “Eight Mile” and sent Chelsom and Fields an audition tape they felt was “phenomenal.” Says Fields: “Omar brought a rawness and an enthusiasm that are a total asset to the ensemble.”

For comedienne Lisa Ann Walter, the role of strident Bobbie, who reluctantly becomes John’s competition dance partner, brought her back to her teenage years, when she did a stint teaching at the Arthur Murray Dance school during disco’s heyday. She recalls: “I taught Fox Trot, Rumba, Waltz, Lindy, Quick Step, Swing and Double Time Swing — until my mother found out that they expected you to go away to South America with these guys for competitions, and she said ‘not my daughter!’”

Walter also had an innate understanding of Bobbi’s own personal journey. “Bobbie is a woman who has been disappointed so many times in her life with men, she’s just angry all the time. But she learns through dance that to succeed you have to trust. You have to trust that your partner’s not going to bang your head into a pillar in the middle of the room or let you fall down or even let you look ridiculous. He’s going to support you, and care for you. Bobbie needs to learn this and it’s a really cool journey her character takes.”

Says producer Simon Fields of Walter: “We needed a woman who has no control over the connection from her brain to her mouth but at the same time is able to be vulnerable, to be a mother, and at the zenith of her dancing performance. You need to be so much behind her and Richard as a couple when they get out on that dance floor – and Lisa just shone as the right person.”

Rounding out the cast are veteran character actor Richard Jenkins as the private detective hired to follow John Clark; teen sensation Nick Cannon as the detective’s witty assistant; and distinguished stage actress Anita Gillette as the namesake owner of Miss Mitzi’s fading dance studio – who herself is transformed as she trains a group of clumsy students for serious competition, and helps John Clark to let his passion for dance show.

For Gillette, the ultimate excitement in the film is what happens when the characters, no matter who they are, hit the dance floor. Gillette says: “I think the greatest thing about playing Miss Mitzi is that once she gets someone out on the floor, they begin to have fun, and they begin to open up, and then… anything can happen.”

* * *

Once the cast was set, the really hard part began. For now the task was to take a group of highly regarded actors and turn them into top-notch dancers capable of showing the comedy, the grace and most of all the sense of possibility inherent in ballroom dancing. It wasn’t like a musical, where the cast members were asked to learn just one style of choreography – instead, each actor had to take on a rapid-fire education in ballroom dancing’s ten different styles.

To accomplish this tough mission, Peter Chelsom brought in acclaimed Australian choreographer John O’Connell to work his magic. O’Connell is one of filmmaking’s renowned dance masters, having previously choreographed Baz Luhrmann’s hit films “Strictly Ballroom” and “Moulin Rouge.” But this was unlike any job he had taken on before. Months before any cameras rolled, Chelsom and O’Connell began the involved process of training the actors at a kind of “ballroom boot camp.”

“We kicked things off with basic research, by going to ballroom competitions and interviewing real winners,” recalls Fields. “We were impressed right away with the immense level of devotion that these dancers have – and we started to realize what a gargantuan job it was going to be to teach actors to dance well enough to create excitement on the screen.”

But the actors approached the challenge with astonishing ardor, working for long hours over a period of months. Richard Gere began rehearsing with instructors in New York almost from the minute he was cast. Aside from his demonstrated flair for the soft shoe developed for “Chicago,”

Gere had little previous dance training. But Gere does have a natural athleticism – he won a gymnastics scholarship to college and avidly practices Tai Chi — and John O’Connell says Gere’s tremendous work ethic made him a star pupil.

Jennifer Lopez remembers hearing early buzz about Gere’s strenuous rehearsals. “I was working on another film, and I would get reports of him dancing in New York,” she recalls. “I kept hearing that he was rehearsing everyday for eight hours! I thought Oh my God, I’m going to have so much catching up to do when I get there.”

During production it wasn’t unusual for Gere to continue practicing after shooting wrapped, sometimes until 3 or 4 in the morning. Gere claims that when it comes to dancing on screen “fear is my greatest motivator.” Yet, the more he learned about the difficulty of true competitive-style ballroom dancing, the harder he realized he was going to have to work. “I don’t think most people understand how athletic you have to be to pull this stuff off,” he explains. “I mean it’s being considered for an Olympic sport, and as goofy as it can seem when amateurs do it, it’s really serious stuff.”

For Gere, the hardest dance to learn was the waltz, which is supposed to be John Clark’s forté. “It’s so slow and so graceful,” he comments, “you have to have full body control to do it well. It’s like doing Tai Chi, where you have to make it look very simple but at the same time you’re using absolutely everything you have. I was often in a flop sweat after the waltz numbers, even though you’re supposed to look like you’re floating.”

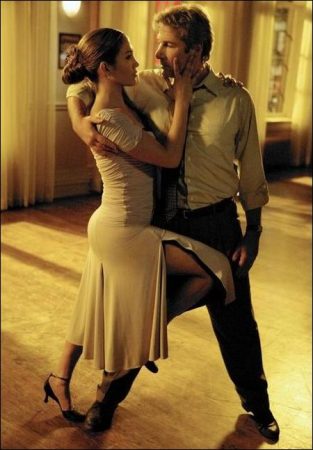

And then there was the late-night tango lesson he has with Jennifer Lopez. Chelsom added the scene to the film, believing it to be the right crossover for Richard and Jennifer – the tango is a classic art form with a language all of its own and as sexy and as hot as it becomes it keeps Jennifer in a the aesthetic place of dance. On the eve of the big competition, Chelsom wanted Richard to have a kind of masterclass in dancing with all of your emotions, a class in expression. Gere places the credit for the scene on Lopez. “To do this very intense tango with an amateur like me required a lot of generosity, patience and grace from Jennifer, which she gave to me. She made it a very good experience,” he says. “I also learned that what makes a dance work is not the steps but whether it tells a story. That’s what makes it come alive.”

Earlier, during his experience making “Chicago,” Gere had learned that hard work among a cast can develop a deeper bond on screen, which is something he saw repeated during the production of Shall We Dance. “I like hard work,” he comments. “And I also like the feeling of working hard with other people. You become very comfortable with people you sweat with and you get to know them in a more real way. It adds to the feeling of a communal effort, which was so important to this story of people coming together.”

The entire cast felt the bonds… and the pressure. Choreographer John O’Connell notes: “Ballroom is a very different technique from other forms of dance because there is so much emphasis on precision, so we brought in a lot of trainers to help the actors every step of the way. Often, it was just a matter of tweaking the way someone was holding his head or her arms. It’s also a dance between partners so it’s different than dancing by yourself because you’ve got somebody else you have to learn to respond to and work with each other, which is the trickiest part of all. “

Even Lopez, who has danced all of her life, found the process of learning the strict discipline of ballroom dance to be highly challenging. “It’s a totally different animal,” she comments. “You can know several other types of dance, and you’ll still feel like a baby when you start learning how to ballroom dance. But one of the things that struck me about it is how fun it was, and I was hoping that we could capture that in this movie. Once you get going, you feel like you’re flying.”

Lopez’s favorite dance turned out to be the tango, which plays such a pivotal role in her character’s friendship with Richard Gere’s character. “The tango has a lot of grit to it, a lot of passion, and also it’s a lot of fun to perform. You can really hit it hard, which is something Paulina tries to teach John.”

For the rest of the cast, the learning process was enlightening but far more physically demanding than they had anticipated. Or as Stanley Tucci puts it: “I knew it was going to be hard, but I didn’t know it was going to be this hard.” Tucci’s particular challenge was not just executing complicated routines – but also adding something extra to the performance to express the piercing humor of his character. O’Connell admits that Tucci was a favorite pupil: “I was very lucky to have someone like Stanley because an actor trying to be funny in dance could be a rather tragic situation if he didn’t have an innate comic style himself, which Stanley does. I made suggestions to him, as in try these steps, but Stanley truly made the movements his own.”

Bobby Cannavale started his dance lessons with no prior experience at all, but found he was a natural. Still, even though his feet took well to doing the steps, Cannavale had trouble getting his body and mind to work together. He says: “For me the hardest part wasn’t dancing but getting into the character while doing the dancing, because for the first couple of months I was busy counting in my head, and the look on my face was one of pure perplexity instead of anything having to do with Chic.”

However, once he overcame that stage, and learned to make the moves his own, Cannavale realized that dance is a formidable acting tool. “You can’t just act with your face when you’re dancing,” he notes. “What’s exciting, is realizing that the body can add so much to what the character is trying to say at all times.”

Since Omar Miller was a late addition to the cast, he had some catching up to do in the dance training, but was pleased to discover that he too had an instant affinity for it. He recalls: “When I first signed on I was like wow, I imagine the dancing is going to be done with some kind of camera tricks or something like that, but no… no fakeness going on here. Do you see my feet twinkling around?

That’s me.” Miller continues: “I had days at first where I might spend four hours just trying to do one single move but I kept trying and trying and then one day it started to work. I discovered that dancing is addictive.”

Lisa Ann Walter thought she might have an advantage because of her past experience at the Arthur Murray Dance School, but the physicality of trying to achieve the extremely strict form and poised stillness of professionals proved difficult no matter her skill level going into the movie. “The body positions you see in real ballroom competitions are unbelievable,” she comments. “You’re bent in these entirely unnatural positions and you stay like that for hours. It’s incredibly hard. But it’s exciting because you’re always improving. For me, I felt like every time I learned something new, I could get a hundred times better the next day.”

Because the actors became more and more proficient at dancing throughout the film, an attempt was made to shoot as much of the dance as possible in sequential order, revealing the cast’s growth from klutzy neophytes to contest-worthy performers, bit by bit. But, as it turns out, that wasn’t always possible.

“We couldn’t always shoot in order, so the cast had a tough challenge: going back and forth between being proficient dancers and comically bad ones,” says Simon Fields. “They would have to wake up some days and have to be show-worthy, and then go back the next day to being utterly dreadful. Every time we began a scene we would have to have the choreographer come on board and coach them to go backwards or forwards to the appropriate level. It was really dizzying at times!”

Adds Richard Gere: “At first, we genuinely didn’t know what we were doing. But once we learned the steps, it was much harder for us to dumb it down and make it purposely burlesque and funny. It turns out it’s easier to learn how to dance well than it is learn how to dance badly.”

Throughout the filming, the stars, very much like their counterparts in the film, found continuous inspiration from the sheer joy and liberation that the very act dancing can bring. Sums up Bobby Cannavale: “When you dance you discover it’s not just about music and steps. It’s about telling a story, about making that connection with passion and with the person you’re dancing with. Watching that happen with the professional dancers on the set, feeling that happen when we danced ourselves, made the movie really come alive for me.”

But the actors weren’t the only ones who had to learn ballroom dance. Director Peter Chelsom decided to dive into lessons, too. “I had had a basic training in dance many years ago and it helped me understand what the actors were doing. The difference is that no-one, and I mean no-one, is going to see me dance!”

* * *

The physical world of Shall We Dance traverses two distinct worlds – that of John Clark’s everyday work and family life and that of the dance studio where the outside world seems to just disappear. Linking these two realms is Chicago’s famous “El” train.

Despite the Chicago setting, much of Shall We Dance was shot in Winnipeg, Canada, necessitating that production designer Caroline Hanania get very creative in her designs. “Luckily, there’s a lot of interesting turn of the century architecture in Winnipeg that has some of that Chicago feel,” says Hanania. “So that was a help, but we did end up building the whole understructure of an ‘El’ train and several building facades to recreate more of a stylish, urban Chicago setting.”

Still, Hanania, who has collaborated on all of Peter Chelsom’s films, knew the most important set had to be the inside of Miss Mitzi’s studio — where so much that changes John Clark takes place. This world of glass, wood and sweat was built entirely on a Winnipeg soundstage. “We wanted the studio to both feel very real but also like somewhere John Clark could never imagine himself being,” she says. “It’s completely outside his normal experience and everything about it, from the colors to the furniture, contrast his life at home and at work.”

Another challenge for Hanania was creating a mirrored room that would work visually for Peter Chelsom and his director of photography John De Borman (“Ella Enchanted”), allowing them to intricately light the dance sequences. “What we did is build the mirrors so that they could be flipped up, down and sideways to get them out of the way, and we also had curtains we could pull over them,” she explains. “This way we could choose when and how to use the mirrors as needed.”

From the production design to the camera work, Chelsom says that, in the end, creating Shall We Dance was “far more complicated than I had ever imagined.”

Even the floors had to be specially created to be at once dancer-friendly and ready to accommodate rapidly moving cameras following on the heels of dancers. Says Chelsom: “I didn’t want too many camera tricks because the dance sequences I like best are when the camera is more of an observer standing back. And then going in very close to capture the thrill. There is no doubling of actors at in this film. Ever. They should be proud of that.”

Shall We Dance? (2004)

Directed by: Peter Chelsom

Starring: Jennifer Lopez, Richard Gere, Susan Sarandon, Stanley Tucci, Bobby Cannavale, Nick Cannon, Tamara Hope, Karina Smirnoff, Anita Gillette, Lisa Ann Walter, Cesar Corrales

Screenplay by: Audrey Wells

Production Design by: Caroline Hanania

Cinematography by: John de Borman

Costume Design by: Sophie De Rakoff

Set Decoration by: Carolyn ‘Cal’ Loucks

Art Direction by; Sue Chan

Music by: John Altman, Gabriel Yared

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for some sexual references and language.

Distributed by: Miramax Films

Release Date: October 15, 2004

Views: 136