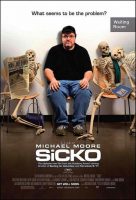

Tagline: What seems to be the problem?

Sicko movie storh4yline. The words “health care” and “comedy” aren’t usually found in the same sentence, but in Academy Award winning filmmaker Michael Moore’s new movie SiCKO, they go together hand in (rubber) glove.

Opening with profiles of several ordinary Americans whose lives have been disrupted, shattered, and—in some cases—ended by health care catastrophe, the film makes clear that the crisis doesn’t only affect the 47 million uninsured citizens—millions of others who dutifully pay their premiums often get strangled by bureaucratic red tape as well.

After detailing just how the system got into such a mess (the short answer: profits and Nixon), we are whisked around the world, visiting countries including Canada, Great Britain and France, where all citizens receive free medical benefits. Finally, Moore gathers a group of 9/11 heroes – rescue workers now suffering from debilitating illnesses who have been denied medical attention in the US. He takes them to a most expected place, and in addition to finally receiving care, they also engage in some unexpected diplomacy.

While Moore’s Sicko follows the trailblazing path of previous hit films, the Oscar-winning Bowling for Columbine and all-time box-office documentary champ Fahrenheit 9/11, it is also something very different for Michael Moore.

Sicko is a straight-from-the-heart portrait of the crazy and sometimes cruel U.S. health care system, told from the vantage of everyday people faced with extraordinary and bizarre challenges in their quest for basic health coverage.

In the tradition of Mark Twain or Will Rogers, Sicko uses humor to tell these compelling stories, leading the audience conclude that an alternative system is the only possible answer.

Q & A with Michael Moore

Why make a movie about the health care system—doesn’t everyone already know it sucks?

One thing I said to my coworkers when we started was that we don’t need to spend a lot of time in the film telling the audience how bad the system is, because they already know. That would be like making a movie now and pointing out that Bush is a lousy president.

How did you originally get the idea for the film?

We started thinking about doing this back in 1999—I wrote the outline and we even shot a couple of scenes back then. I had a TV show called The Awful Truth and for the first episode, we filmed a guy who was having trouble getting his insurance company to pay for an organ transplant. Within a matter of days, we were able to save the guy’s life and get him his operation.

We thought—what if we made a whole movie out of this, just take 10 people and spend 10 minutes of the film on each of them, trying to save their lives. Then the Columbine incident happened and we put it aside to make that film. Then the Iraq war was starting and there seemed an urgent need to make a film about that. But it’s always been on the forefront of our minds.

You started by asking readers of your website to submit their heath care horror stories –did any one theme resonate in their responses?

Yes—it was a frustration with the bureaucracy that exists to essentially make it very difficult to get help or to get that help paid for, even though people or their employers have paid into the system for it. One of the big myths is that the private sector is the way to go because there’s less red tape and it’s more efficient. In fact, the opposite is true, especially with health care. Health care companies spend upwards of 25% of their budgets on paperwork, administrative costs and other red tape, while Medicare and Medicaid only spend around 3% for administrative costs.

You read thousands of these horror stories—how did they affect you?

It was very difficult. You had people saying, “I’m going to die if I don’t get help…” or “My mother is dying…” You feel helpless about what you can do, and it deeply affected everybody working on the film. We also knew most of the film wouldn’t be focusing on these horror stories, but rather we’d be explaining how they wouldn’t be going through any of this if they just lived in Canada—and for some people who wrote in, the border was just a few miles north.

Who deserves the blame for the health care mess: the US government, the big drug companies or something else?

It’s the system itself. For the most part, the system is based on profits and greed. When it comes to people’s health, profit should be nowhere involved. If anyone suggested that, say, the school system should be making a profit, they’d be looked at as if they were from Mars. Nobody would ever say the city water department should be turning a profit—without water you don’t live. Health care should be the same way, and it is that way in other countries.

After spending over a year making SiCKO, what are the three most important things you believe would improve the US health system?

We need to eliminate private health insurance companies—that’s the biggest single impediment to making sure everybody who needs to be taken care of receives the help they require. The pharmaceutical companies should also be highly regulated, like ConEd. A lot of people need medicine to survive, but to allow pharmaceutical companies to jack up prices and make it impossible for some people to get the drugs they need to live is criminal.

Finally, there’s We the People. Health care needs to be in the hands of the people, just like the Fire Department and the Police Department are in the hands of the people instead of a private company like Halliburton. We all have to become more active in caring about these things, and start thinking of ourselves as part of a group larger than just me, myself and I.

You need insurance to make movies. What was that process like for SiCKO?

As you can imagine, if you’re making a movie about the insurance industry, getting insurance to make your movie isn’t the easiest thing. They were not very eager to insure us. We were able to get very good health insurance for everyone, but getting what’s called “production insurance” covering errors and omissions and stuff like that wasn’t easy. Every big company refused us,

Did any of the Americans you filmed have any positive outcome to their stories?

Yes. A few of those who were willing to fight back and demand that their health insurance company do the right thing eventually found some relief. Laura, the young woman whose insurance company wouldn’t pay her ambulance bill wouldn’t take no for an answer and eventually Blue Cross relented. The two young people who were rejected because they were too fat or too thin eventually found health insurance companies willing to insure them. Maria

Wantanabe received only minimal relief through her lawsuit and is now appealing. Her lawyer is optimistic. The point of all of this is why should anyone have to fight so hard just to get the help they deserve? When will we start to realize health care is a human right?

Unlike your previous films, you shot much of Sicko overseas. What did you learn from you’re your location shooting?

It was eye-opening, exhilarating and depressing. We continued to be surprised by what we discovered. We thought we knew the issue fairly well, but every corner we turned we found something new. It was depressing because, as Americans, we kept thinking: we come from the richest country on earth, so why don’t we have free health care, too? Overall, it reminded me about the importance of getting out of the house. About 80% of Americans don’t have a passport, so most of us don’t get to see the whole world and what’s going on. Ignorance is never a healthy thing – you can’t make the best decisions without having all of the information. That’s true in our daily life, and that’s true in our political life.

Does any candidate have a solid health care plan at this point, or are they just making vague generalizations?

Yeah, they don’t seem to want to grapple with the real issue. It’s very sad. Even the wellintentioned people like John Edwards—his plan seems to be to take our tax dollars and put them into the pockets of the private insurance industry. That is not the solution. Obama hasn’t put together his plan yet, though I’m hoping he’ll come up with something good. And then, of course, there’s always the candidate who hasn’t entered the race yet, but who won the office back in 2000. What he’s been saying on this issue since 2003 is the best.

Political pundits, special interest groups and big corporations often attack your films. Who do you think will fight you on SiCKO?

Those who profit from people’s misery and illnesses are not going to like this film. Yet Sicko may have the widest audience of any film I’ve ever done, simply because so many people—regardless of their political stripe—are affected by this issue.

Do you think your controversial image might hurt?

Why is it that I’m considered controversial? What have I done? I made a movie about people in my hometown that suffered as a result of GM pulling out. I made another movie because a bunch of kids were killed at Columbine High School and I didn’t want that to happen again. And I made a movie because, early on. I took a wild guess and told the American people from the stage of the Oscars that we were being lied to about weapons of mass destruction and I got booed. These days, I get a lot of Republicans stopping me on the street and apologizing to me. They now see I was trying to warn them the Emperor has no clothes. At this point, I’m very squarely in the middle of the mainstream majority.

About the Production

Sicko had its origin almost a decade ago, when Michael Moore shot a segment for the premiere episode of his 1999 TV show The Awful Truth about Chris Donahue, a dying man battling his insurance company over a pancreas transplant. The story detailed how Donahue made seven years of payments to health care provider Humana, only to be denied coverage for the life-saving operation — that is, until Moore intervened by proposing a mock funeral and the company relented to avoid a total PR disaster. After the back-to-back success of his Academy Awardwinning Bowling For Columbine and the top-grossing documentary Fahrenheit 9/11, Moore is returning to the American health care crisis, this time flaring it up for the big screen.

“The film is about health care, and it isn’t,” says Moore. “As with all my films, I take a subject and use it as a vehicle to address larger issues and bigger ideas. In this case, I’m trying to answer a larger question: why are we, the largest western industrialized country, without free universal health coverage for everyone? Why us? What is it about us?”

As word spread of Moore’s latest film concept, the U.S. corporations whose massive profits come from health care began having aneurisms. Ken Johnson, senior vice president of the Pharmaceutical Researchers & Manufacturers of America trade group told a journalist that industry executives were “freaking out and pulling their hair out.” Indeed, Big Pharma went on lockdown.

“Michael Alerts” were sent out to company employees working for at least six major drug companies, warning them to watch out for Moore and his film crews. “We ran a story in our online newspaper saying Moore is embarking on a documentary – and if you see a scruffy guy in a baseball cap, you’ll know who it is,” a Pfizer spokesman told the L.A. Times. Late last year, CNBC reporter Mike Huckman noted “the level of paranoia was extreme” when he covered a drug company’s analyst conference, questioning the reason for the high anxiety as “The Michael Moore Effect.”

Yet, from the very start of his project, Moore was always just as interested in honoring the victims our health care system as in unmasking its villains. In February 2006, he issued a call on his website michaelmoore.com, asking readers and fans to send in their personal health care horror stories. His message read, in part, “If you’d like me to know what you’ve been through with your insurance company, or what it’s been like to have no insurance at all, or how the hospitals and doctors wouldn’t treat you (or if they did, how they sent you into poverty trying to pay their crazy bills)… if you have been abused in any way by this sick, greedy, grubby system and it has caused you or your loved ones great sorrow and pain, let me know.” Nothing could have prepared him for the response – a deluge of more than 25,000 e-mails in just the first week.

A close friend told cancer survivor Donna Smith about Moore’s website request, and since Smith had enjoyed Fahrenheit 9/11 she thought she’d check it out. “I fired off a quick, curt e-mail, just around two or three paragraphs, and didn’t think anything would come of it or that anyone would care,” says Smith, the wife of a cardiac patient who moved into their daughter’s home after insurance costs devastated them financially. “I was venting in that e-mail, it was just sheer frustration. But I was also hoping, against all odds, that somebody would hear from those of us who played by the rules and made it a priority to pay their premiums—and yet were still going under. To have someone like Michael listen and expose a problem that millions of Americans are facing every day gave us a dignity we haven’t had for years.”

Early on during production, Moore made an important decision—to focus on one particular area of health care rather than covering the unwieldy issue from every conceivable angle. “We had our own ‘Axis of Evil’: the pharmaceutical industry, the hospital business, and the insurance carriers,” says O’Hara. While major pharmaceutical firms are profit-obsessed corporations that bankroll Washington politicians and often lie about their research and development costs, the filmmakers viewed prescription drugs as “a necessary evil” that may ultimately help patients. The same can be said for hospitals—though they, like Pharma, should be regulated and run more efficiently, people obviously need them.

Such allowances, however, couldn’t be made for private insurance—“a completely unnecessary factor when it comes to health care,” says O’Hara. To make his point even more emphatic, Moore decided not to concentrate his efforts on the 45 million Americans who lacked medical insurance, but instead on the majority who are covered and were denied benefits or became strangled with ridiculous bureaucratic red tape.

The stories speak for themselves. But behind the stories lies the question of how insurance companies literally can get away with murder. Scores of industry insiders and whistleblowers contacted Moore, eager to share their stories on the record about how insurance companies make billions in profits by keeping needed benefits away from those patients who deserved them. “I was told I was not denying care, I was denying payment,” went one familiar refrain.

Fortunately, when the medical madness got too heavy or too dreary around Moore’s offices, a healthy dose of humor would help lighten things up. A large sign stating “This Is A Comedy” was posted near the entrance to remind sleep-deprived staffers that laughter is the best medicine. Even a sad little houseplant that wilted in a corner office for weeks provided comic relief when someone hung a note on it that said “This Plant Needs Health Care.”

Shooting first began across the United States, with crews sent out to shoot various patients’ stories region by region—for instance, a West Coast jaunt took the production to Los Angeles and San Francisco, a Texas whirlwind included shoots in Houston, Austin, Brownsville, McAllen and Dallas, while another Southern trek filmed people across Florida and elsewhere. To demonstrate how US health care has become so acutely diseased compared to much of the civilized world, the crew visited several other countries including France, England and Canada.

In the end, between 150 and 200 unique stories were documented over more than 130 days of shooting—compared to a mere 38 days of filming on Fahrenheit 9/11. More than 500 hours of film were eventually shot—the most ever exposed by Moore for a single movie project.

When Moore and his crew returned from shooting, the real surgery began: editing those hundreds of hours of interviews and other footage into a movie. Joining Moore again in the cutting room was Fahrenheit 9/11 editor Chris Seward, along with new team members Dan Swietlik (winner of an ACE Award for his work on An Inconvenient Truth) and Geoffrey Richman (God Grew Tired Of Us, Murderball).

Ultimately, believes Moore, Sicko will not only expose a failing system and offer solid alternatives, but also show his growth as a filmmaker. “Bowling For Columbine was not Roger & Me, and this is not Fahrenheit 9/11,” he says. “When people go to the movies they expect something that will make them laugh or cry or think. They want something fresh and new, and I’m not interested in doing the same thing over again. I think some people will be surprised by the tome of this film.”

“I knew this would be a challenge,” he concludes. “There’s not one character or one company to hate in Sicko, there’s no single antagonist like Roger Smith or Charlton Heston—it’s an entire system. Both the audience and I have to work a little harder with this film because it’s not so black and white. Let’s face it: me marching up the steps to the CEO’s headquarters for the umpteenth time isn’t very interesting. It’s not that I wouldn’t do that again, but with Sicko I wanted to get through a whole film without having to bang on the door of power. I don’t want the audience going out into the lobby saying ‘Gee, Mike really kicked some ass.’ They have to kick the ass themselves. This situation is only going to end when everyone stands up and says, ‘Enough!’”

Sicko (2007)

Directed by: Michael Moore

Starring: Michael Moore

Screenplay by: Michael Moore

Cinematography by: Andrew Black, Jayme Roy

Film Editing by: Geoffrey Richman, Chris Seward, Dan Swietlik

Music by: Erin O’Hara

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for brief strong language.

Studio: Lionsgate Films, The Weinstein Company

Release Date: June 2, 2007

Views: 59