Tagline: The bravest place to stand is each other’s side.

Stop-Loss movie storyline. Sgt. King is a decorated Iraq war hero that is trying to resume his life after his tour of duty. His two buddies and him have been trying to make peace with civilian life. Then, against his will, the Army orders him back to Iraq. It is ridiculously hot, the kind of heat that causes asphalt to shimmer like a mirage.

The infrequent wind only kicks up fluffy cotton tufts and dust. Nonetheless, the occasional green onion field flashes by, a testament to modern irrigation, determination and the old fashioned migrant labor that tends to the land. This is Brazos, Texas and it is home to Staff Sgt. Brandon King (Ryan Philippe) and Sgt. Steve Shriver (Channing Tatum). They are returning as war heroes in a tin can of a bus, alongside their wartime buddies.

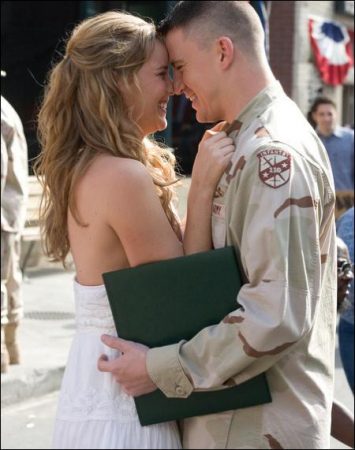

They will take a bow in front of cheering hometown crowds and then they will try to resume civilian life as Brandon King and Steve Shriver, best childhood friends. They went to war with noble, patriotic intentions, they served valiantly and now they will try to leave it behind. Friends and family help – especially Michele (Abbie Cornish), Steve’s fiancée, who is like a sister to Brandon. Still, the ghosts of Iraq follow them home and manifest in drunken brawls, deteriorating marriages and fraying friendships. Brandon, the squad leader, tries to hold his comrades together.

Then, unexpectedly, Brandon receives orders to return to Iraq. Invoking a measure called Stop-Loss, the Army indefinitely extends Brandon’s enlistment. It upends his entire world and as he struggles to make sense of it, he turns to one of the only people he can trust – Michele. She becomes his confidante and accomplice, even as Steve tries to bring his friend and former CO to his senses and, ultimately, back to the military. Love and loyalty are tested as Brandon King, decorated war hero, goes AWOL. With Michele’s help, he races across the U.S. – a fugitive from justice in the country he fought to protect – in search of a way out of his predicament.

About The Production

Initially, writer-director Kimberly Peirce had seen the movie as a character piece in the style of such classic road movies as “The Last Detail.” But as she got deeper into the material, she was also affected by seminal war movies as varied as “The Best Years of Our Lives,” to “Apocalypse, Now” “Platoon,” “Born on the 4deeper into the material, she was also affected by seminal war movies as varied as “The Best Years of Our Lives,” to “Apocalypse, Now” “Platoon,” “Born on the 4th of July and “Coming Home.

The project took a more personal turn when Peirce’s younger brother, then 18, enlisted in the Army after the events of September 11, 2001. “I understood his desire to ‘get the people who had done this,’ but the idea of my own brother carrying this out was devastating,” she says. “None of my friends or family knew anyone in the military. Now we were a military family. He joined the 10th Mountain Division attached to the 82nd Airborne. He prepared for war while we were fighting in Afghanistan and entered the war in Iraq in September 2003. I was concerned for his safety and worried about the emotional and spiritual toll this would take on him.

“In an effort to understand what my brother was going through,” she continues, “I started making a documentary on our soldiers. I interviewed soldiers, asking them why they joined, what they experienced at war (killing, not killing, seeing their men killed and wounded), and what they experienced upon their return – specifically, how they struggled to re-assimilate into society.” The research began to illuminate discontent among the soldiers about the war, what they were fighting for and the way it was being fought. “As a result,” says Peirce, “an increasing number of servicemen were going AWOL. Kathie Dobie wrote an excellent piece about it in Harper’s magazine, ‘AWOL in America.’ We began searching these soldiers out and interviewing them on the run in America and those who had settled abroad.”

During her brother’s first leave from Iraq, Peirce stumbled on a treasure trove of original material relating to his and his fellow soldiers’ war experiences. “I found my brother in our living room sitting a few inches from an oversized TV, mesmerized by what was playing: soldier-shot and edited images of life and war in Iraq cut to rock music. There was something completely unique and immediate about these images – images of soldiers doing raids, seeing combat, cruising in Humvees – mostly shot with lightweight

And one-chip cameras that the soldiers had mounted on guns, Humvees, sandbags, or whatever they could attach them to; images of weapons, fighter jets, bombs going off (downloaded from other soldiers and from the internet (from Defense Weapons companies such as Lockheed Martin and Boeing) then edited on I-Movie or Final Cut and put to music – rock, sentimental, patriotic. It was a personal, unadulterated look at combat as these young men were experiencing and signifying it. I studied the videos he brought home and located more videos through other soldiers. These small home movies were like anthropological finds – told entirely from the soldiers’ point of view. They opened many windows into the lives of these guys and my brother.”

Once he was back in Iraq, Peirce’s brother text-messaged her the story of a friend, a decorated soldier who had done his time and was ready to go home to his wife and child when he was Stop-Lossed by the Army, “which meant that despite the fact that he’d completed his contract, the army was breaking that contract and sending him right back into the combat zone – against his will,” she discovered. “So, I turned my research toward understanding what Stop-Loss was and how it was affecting the troops and their families. In military terms, ‘Stop-Loss’ means not letting a military member separate or retire once their required term of service is complete. Congress first gave Stop-Loss authority to the Department of Defense right after the draft ended. It was meant to be used in a time of war if the President needed to retain troops to defend the country.”

But the military didn’t use this authority until the Gulf War when President George H.W. Bush imposed Stop-Loss on virtually everyone in the military. “Recently, it was used again, at a time when the war was apparently over, and when enlistment rates were radically falling,” says Peirce. “I found out that tens of thousands of soldiers (an estimated 81,000) had been Stop-Lossed. Many of them were sent back to second and third tours that were deadly. A number of soldiers were calling it a “back door draft” and doing everything they could to fight it – from going to their commanders and their chaplains -who were not budging -to bringing a class-action lawsuit, which failed, to getting thrown in jail, going AWOL, even leaving the country.”

The very personal nature of these stories inspired Peirce to explore the idea of transforming her planned documentary into a feature film, of which the Stop- Loss controversy would be the spine. “In the film, these young men feel a sense of duty and obligation, so they sign up to serve their country,” says Peirce. “But their black and white sense of patriotism and duty is turned upside down when they are faced with impossible circumstances. They end up committing a series of acts that force them, in the deepest sense, to question who they are, what they are and what they believe in. In the process, two lifelong friends who are so alike at first are torn apart by the war time experiences they have had to face.”

Peirce continues “But their black and white sense of patriotism and duty is turned upside down when they are faced with impossible circumstances – our soldiers find themselves fighting an urban war against what many of them have called “the faceless enemy,” an enemy who hides and fights from within the bedrooms, hallways and kitchens of the local population, an enemy who engages in unconventional attacks –IED’s, car bombs, etc., that significantly diminish the U.S. soldiers’ ability to protect themselves and their men.”

During the writing of the film, Peirce and Richard continued to interview soldiers, incorporating their experiences and comments. “My brother (who had returned from Iraq and lived in upstate New York) and other soldiers we knew would look over the dialogue and scenes and make sure they were accurate from a soldier’s POV.”

Casting was a key component for Peirce and the filmmakers in telling the story. For the key role of the heroic, conflicted Sgt. Brandon King, Peirce was looking for someone who could express the strength and masculinity to lead men into and through battle and also possess the warmth and humor that is necessary to be at the center of these men’s lives. “It required someone who could depict the patriotism and innocence required to go to war on behalf of his country, but who was also introspective enough to question what he had done when he needed to question it. Because it’s essentially a point-of-view movie (one guy’s journey) and he’s in every scene, he had to be able to carry us through the entire story.”

Peirce was excited when actor Ryan Phillippe agreed to take on the role. “Ryan brought something unexpected to the part,” she affirms. “Not only could he act it, but he seemed like Brandon. He seemed like someone who would have signed up for this war, who would have been the leader, who would have killed in order to protect his men and been devastated when he lost them, who would have questioned, who would have gone on the run and who would have ultimately gone back to war for his family, his friends and his country.”

Phillippe says that, as always, his main priorities in deciding whether to take on a film role are the talent of the filmmaker and the quality of the material. For him, “Stop-Loss” was the perfect melding of script and director. “I truly believe Kim Peirce to be an artist,” he attests. “If you look at her first film, she’s clearly talented. As for the script, I love reality-based material. This is not a true story, but many men have lived it and when a project is grounded by that kind of dramatic weight and truth, you feel convinced that you’re telling a story that needs to be told.”

To play an Iraq War-era soldier, Phillippe plunged into deep research. One of his primary sources was Peirce’s brother Brett and the specifics about his real-life experience that he shared with his sister, as well as the videotapes he brought back from the Middle East. “I watched hours and hours of video camera footage that the soldiers shot of each other to get a sense of their camaraderie,” he says. “I also viewed many of the excellent documentaries that have been made about the Iraq conflict. Also, I got really into the military aspects, which I tend to do when I get involved in this kind of movie. You really want to make sure you know how to behave and appear like a soldier.

I think you’re doing these men a service if you do your best to appear legitimate. It was very important for me, and for all the other actors, to look like the real deal. We were fortunate to have Jim Dever as our technical advisor. He’s the best in the business and I’d already worked with him on ‘Flags of Our Fathers.’” made about the Iraq conflict. Also, I got really into the military aspects, which I tend to do when I get involved in this kind of movie. You really want to make sure you know how to behave and appear like a soldier. I think you’re doing these men a service if you do your best to appear legitimate. It was very important for me, and for all the other actors, to look like the real deal. We were fortunate to have Jim Dever as our technical advisor. He’s the best in the business and I’d already worked with him on ‘Flags of Our Fathers.’”

In speaking of his experience of working with Peirce, Phillippe says “I’ve had the opportunity to work with Altman, Eastwood and Ridley Scott, and I put her right up there with them. I think she’s maybe tougher than any of them and she’s a real artist. She’s got this drive and is determined to get what she wants, and that’s what a director has to do -be decisive, authoritative and unrelenting.”

The character of Michele was inspired by real military wives Peirce interviewed, women she found “fascinating – for the challenges they face, the fears and hopes they feel while their men are at war and struggles they face upon their men’s return,” she says. “Many spoke of feeling committed no matter what, but felt old before their time; many said they felt they lived two lives, one when he was home and one when he was away. Many spoke of how the other wives banded together to deal with the loneliness and the strangeness of their soldier’s return: men meeting their newborns for the first time after being away for a year; the sudden bouts of anger and violence; how they couldn’t go out to a bar without having a fight/brawl erupt; how going to Dunkin’ Donuts was a challenge when they were overwhelmed by the number of donut flavors, being forced to make a choice about what they ate for the first time in months.”

The film intrigued Cornish “because it made contemporary issues personal. It was an interesting exploration of what is happening in the world as told through a man’s desire to disengage from the war and how that affects his family, and the people around them. I also liked that it was very much an ensemble piece,” Cornish says. Her character makes some life-altering decisions in the course of the movie. Cornish attributes Michele’s bold choices and spirit to an innate core of honesty and fortitude, qualities that also appealed to Cornish.

“When first exploring the character of Michele, I found her honesty and direct nature to be very strong. She has a big heart and is a pillar of strength many times throughout the film. Michele to me was a symbol of the realizations of war, its effects on both Iraq and its occupants and also the soldiers and their families. Michele embarks on a road trip with her friend but comes away a changed person. The idea of playing a Texan like Michele, a small town girl dealing with the effects of war in the same world we live in today, really appealed to me.”

Of course, Peirce also was a huge influence on Cornish. Cornish particularly appreciated and admired Peirce’s passion for the project. “Kim engaged herself very much in the story of the characters and held them very close to her heart. She really enjoyed watching the film come to life and seeing the actors bring the words off the page. It was great to work with a director who so clearly loved and adored the characters so much,” Cornish notes.

Steve Shriver is another complex, multi-faceted young man, someone whom Peirce refers to as “a true believer” and was inspired by a number of real soldiers Peirce interviewed -“guys who loved their wives, who loved America, but after fighting never really came back and ultimately needed to go back to war to feel complete. Though I came to understand and love these guys and saw the heartbreak they faced in acknowledging and allowing themselves to live out this truth about themselves, the challenge in writing Steve was in depicting him honestly, with dignity and passion, so that we bring the audience all the way inside this guy, why he feels and acts as he does, why he must go back.”

Peirce auditioned rising young star Channing Tatum for the role and says she was impressed by his emotional depth and maturity, his range and his ability to take direction. She immediately championed him for the role and never regretted her choice. “Channing was sheer energy on the set, willing to try anything, go anywhere emotionally and bare that side of himself – his vulnerability, his sense of dignity, his feelings of brotherhood for the other men, that was so necessary in becoming that character.”

Tatum was both flattered and intrigued by the offer to play Steve. “’Stop- Loss’ was honestly one of the most raw, heartfelt scripts I had ever read. Since I was a kid I’ve been fascinated by soldiers -about their morality and their ideals so to have the chance to play one was very exciting,” says Tatum. “And that was just at the start. It only got more interesting as we got deeper into the role.”

Returning to civilian life proves to be arduous for Steve, and Tatum says it’s because “in Steve’s head, he fell in love with the military. He found his place in life and his journey in the film is to figure out that it’s the military he’s really married to, and that’s very hard for him.”

But none of his insights into his character could have taken full form without the guiding hand of his director, he claims. “Kimberly is an absolute genius. No one, in that short amount of time, has ever been able to open my eyes to a character the way she did. Steve is a sniper at heart and what they teach you in the military is to be laser specific.”

The dynamic among the characters of Brandon, Steve and Michele is equal parts personal and political. The two old friends and comrades in arms, Brandon and Steve, come to distinctly different conclusions about the war in Iraq and their roles there, and their reactions change their relationship forever. Steve and Michele’s relationship also disintegrates, all against the backdrop of Brandon’s “stop-loss” orders.

“Steve’s involvement in the war begins to take its toll on their engagement and their wedding is pushed further and further back until Michele has had enough. I spent some time (on location) in Austin (Texas) talking with women who have had boyfriends and husbands at war, most of them expressing feelings of fear, anxiety, loneliness and a separation between themselves and their partner when they returned. Throughout the film, Michele says it’s a sense of freedom in her life, that she can’t be (just) a military wife and that’s the only life Steve can provide, assuming he ever commits to her,” Cornish says.

“I think that anyone who has had a family member who has gone to war has struggled with the changes in their loved one when he or she returns home,” says Peirce. “Who is this person now…what has the war done to him—and to us? That is one of the key situations we wanted to address in this film.” Of course, Brandon, Steve and Michele are not the only ones having trouble adjusting to civilian life. The character of Tommy, while able to channel his smoldering rage and violent temperament to good effect during battle, cannot contain it easily in peacetime – with devastating consequences. Peirce set her sights on the prominent young actor Joseph Gordon-Levitt for the pivotal role. “And I did not want to compromise. I had to have Joe. He’s one of the best actors of his generation,” she says. Again, her instincts proved correct. “He was phenomenal to work with – a true method actor.”

Gordon-Levitt had a unique take on the character. “I think Tommy left home and joined the Army partially to escape demons at home and found a real family, found more connection and love in the Army than he had at home. think that when he comes back, he first has the same problems a lot of guys have when they come back but, for him, the old demons rear their heads again alongside new ones he has brought back from Iraq,” says Gordon-Levitt.

It was the script coupled with an opportunity to play a soldier that attracted him to “Stop-Loss,” he continues. “There are very few really good scripts so whenever I read one, it stands out. It was well written and a page-turner and seemed like an honest and heartfelt statement about what was going on today.

It’s brave enough to assert that nothing is simple, especially when it comes to war and being a soldier and what happens when soldiers come back. To play a soldier appealed to me, I had never played a soldier and that life fascinates me. I have a lot of respect for what a soldier does, and having gone through this experience I’ve gained even more. I don’t come from a military family. My grandfather fought in WWII, but my dad and my mom were peace activists in the ‘60s. I wasn’t allowed to play with G.I. Joes when I was a kid. Part of what I love about acting is to learn and explore facets of humanity that are different from me. A soldier is just about as different from me as I can possibly imagine,” Gordon-Levitt says. Some of that respect, he says, came from meeting with real soldiers as part of his research prior to principal photography and, he adds, another appealing aspect of the film was the opportunity to work opposite Mamie Gummer, who plays his on-screen wife, Jeanie. The couple endures a tumultuous, anguished relationship but, at first, perhaps having to do with Tommy’s taciturn nature, much of their connection is unspoken.

“The second day I worked, there is a little moment in the script, it’s literally two lines of stage directions. Kim trained the cameras on us – they weren’t recording sound but while this whole other scene was going on, Kim had us improvise this. It was really early in production so, for me, it was a great opportunity to get into the skin of Tommy and his relationship with Jeanie. Mamie was perfect. It’s a really different thing to do a two minute, improvised take rather than a scene on a page. Mamie was so genuine,” Gordon-Levitt says. He adds that this was a good example of Peirce’s directing style, which he describes as “very actor-oriented.”

“Kim really knows how to talk to actors, to communicate in a way so that you instantly get it. She doesn’t even have to say very much – she’s been living with these characters for so long and is so passionate about the work, she knows exactly how to get to the truth of their story and how to bring us there too,” adds Mamie Gummer.

This quality was especially helpful because, as Gummer points out, the fraught dynamics of Tommy and Jeanie’s relationship are never overtly stated but rather revealed through the story. “In these big group scenes, Joe and I had to do a lot of improvising to create a relationship without having written dialogue. Occasionally, Kim would just whisper something in my ear, a small note that would be so right on. It helped that Joe was a great actor and a great guy,” Gummer says.

Gummer auditioned for the movie a year before cameras rolled, and the part of Jeanie appealed to her in particular. Her character was not featured in every scene but instead of returning home during her downtime, Gummer elected to remain in Texas.

“I just loved, loved the story, this script, this girl, this part. It was so far removed from my little New York City self, to come down to Texas and live in this world. I came across and interview with an Army wife talking about adjusting to him being back and the challenges that she faced. That was very helpful. Jeanie grew up in Texas, Michele is her best friend, they all went to high school together. The guys came back to Brazos after basic training and it seems like it must have been a whirlwind relationship and courtship, they got married right out of high school. Living in Texas, spending time here, watching these girls was really something,” she says.

The production began filming in Texas in early August. Peirce sat down with each actor before the rehearsal “to get to know them, absorb who they are, what’s important to them, how they see themselves. Whether they know it or not, they generally tell me their life story as if they were the character. Once I feel they’ve told me all the essentials and I have a feel for them, we naturally start talking about the character.”

After rehearsal, she again met with them individually and then paired them up based on the relationships they have in the film and their scenes in common. “Rather than reciting lines, I ease them into ‘getting the scene on its feet,’” says Peirce. “We work loosely, get to the core of the scene emotionally, what each character wants, how they go about getting it; we improvise it and wonderful stuff comes out.”

Once production commenced, before shooting each day Peirce had a general run-through of the scene, loosely putting it on its feet and letting the actors find their way through the space. “It’s basically to help the scene find its natural shape and then to push on points of conflict,” she says. “I’m always amazed at the new level of clarity we all have when the actors run through the action and dialogue with other actors on the set.”

Working alongside her during the rehearsal process was director of photography Chris Menges. “I’d rehearse a scene until the point where it had a natural and dramatic shape,” says Peirce. “He’d watch the rehearsal and generally figure out where to put the camera (and where to move the camera) so the scene plays out in one shot. That gives it the advantage of retaining the inherent dramatic shape of the scene. Then we can go in for more movement.”

Menges excelled at utilizing handheld cameras, Steadicams and a crane, when needed, which Peirce says allowed her to capture a sort of dynamism and energy as well as a sense of intimacy. “And he’s phenomenal with light. He tends to go with natural light whenever he can.”

The cast and crew stayed in Austin, the cosmopolitan state capitol, home to the University of Texas and a world-famous music scene. However, most of the film’s locations were in outlying small towns, such as Lockhart, Texas, the self-proclaimed Barbecue Capital of Texas. One of the movie’s pivotal sequences took place there – the parade in which the town welcomes home its war heroes and the subsequent awards ceremony. This also happened to be the first scenes filmed in the movie. Lockhart was the perfect venue, with its wide streets lined by Norman Rockwell-esque shops in brick and Victorian-styled buildings and an eye-popping courthouse with mansard roofs, colorful turrets and a high central tower featuring a four-way clock. Equally important, the residents enthusiastically welcomed the film company and nearly 600 townsfolk signed on to be extras, cheering the returning soldiers over the course of two days.

One of the key sequences, in which Tommy shoots his wedding gifts and the tensions and rifts between Brandon and best friend Steve begin to surface, took place at a sprawling ranch known as the Double C. The Double C provided the perfect, vast expanse of desiccated grass and thatch of gnarled trees that provided some shade for the actors during the first part of the scene, set during the day. The night work required a “hunt club,” where Brandon and Steve’s friendship would begin to fray. Production designer David Wasco created a hardscrabble, tin structure that melded perfectly into the beautiful but brutal landscape.

“The script called for a dusty, dried grass kind of place with scraggly oaks. At first, we looked for an existing deer camp, which is essentially a shack. It’s the most rudimentary kind of cover -a series of interconnected cardboard boxes. Ours was board and batten, with standing seam tin for the roof and walls, metal and fiberglass insulation, remnants of carpet on the wall, not pretty. We also had to provide something that was film friendly, so that the camera and lights could be in any position. So, we were lucky to come to the Double C Ranch, which is a multi-thousand acre ranch that offered so many possibilities. It provided a place for the earlier portion of the scene, the “target practice” sequence, and then Kim and the actors could move organically to the deer camp, as they do in the script, which we built nearby. It was essentially a wild-walled movie set – if we would have gone to a practical location, we would have been much more limited, in terms of the shots we could have achieved,” Wasco says.

Wasco adds that the unprecedented drought that summer made for good production design. “This is as authentic as you’re going to get. This was one of the few opportunities in the movie that opens up to show true Texas prairie. We were in the midst of the strongest drought in memory, which gave us these golden fields and dusty prairie, which looks beautiful on film. It’s quite a heartland America thing that is such a contrast to Iraq and New York,” says Wasco.

Wasco adds that in general, his color scheme was a gradual “spiral down with Brandon. As we go on the journey with Brandon and his circumstances become increasingly dire, the colors go darker and darker, until they become almost monochromatic. The only break in that patina is in New York, where, of course, the colors are much more vibrant and jarring.”

Costume designer Marlene Stewart followed a similar color pattern – at the start of the film, as the characters tentatively begin their new civilian lives, the tones are brighter – Steve in his patriotic red, white and blue checked shirts, Michele donning a soft pink top, a fresh white sundress and flouncy red party frock, Brandon favoring a maroon shirt. As the movie proceeds, Steve relies on his Army fatigues while Brandon and Michele, on the run, tend towards gunmetal gray and dark blue non-descript attire.

These looks did not happen by chance and even the more pedestrian garb merited scrutiny prior to principal photography. Stewart, the actors and Peirce participated in several costume and camera tests, to ascertain the best cut of the pants or the length of a t-shirt, in addition to the specific hues that would be used. While this process is common in moviemaking, at first, “Stop-Loss” would not appear to be “a costume movie” that warranted such scrutiny. Stewart demurs.

“I find that even on a ‘simple’ costume, there is the same amount of discussion, especially in a movie like this one, where the characters have to ‘live’ in one costume for a long time,” she says. “I always prefer to have camera tests before production begins, with the DP, the director, the production designer and, of course, the actors, to see how the cut of the clothes look, how the colors react with skin tones and film stock. That way, everyone knows and decides and is in on the process.”

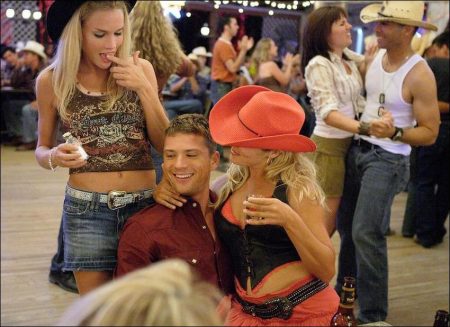

Menges’ trademark, however, is to illuminate sets via practical lights that are part of the scene. This signature practice was best seen in what became known as the Cattle Club. Club 21, in Uhland, Texas, a well-known honky-tonk bar, became the setting of a pivotal party scene in which drunken fun leads to a barroom brawl that reveals the difficulties the soldiers face returning to civilian life. The production ended up filming there for three nights and because the camera, usually a Steadicam, often revealed 90% of the set, lighting it with traditional key lights and the like was a difficult proposition. Menges’ solution was to string a canopy of 5000 Carney lights above the set. David Wasco’s production design augmented the look with neon signage above the stage where a band played tunes by which to two-step. Whenever Menges’ team had to shoot close-ups, his team would produce a white cardboard card with a coiled ring of small white lights affixed to it. This portable, bespoke rig allowed him to softly and swiftly illuminate the actors without compromising the framing of the shot.

Retired Sgt. Major Jim Dever, the film’s military advisor, was consistently on set. With his ramrod posture, his high and tight haircut, and matter-of-fact but positive attitude, he was a conspicuous and welcome presence. Whether it was corralling extras into military formation during parade scenes or teaching Channing Tatum how to fold a flag at a funeral, he was always ready and available. The male cast members got to know him better than they may have wanted at boot camp, where they slept in cots trimmed with mosquito netting, endured classes on and drills with weapons, firing 6,000 rounds during the course of their training.

They began their day at 5:30 am with reveille and by was a conspicuous and welcome presence. Whether it was corralling extras into military formation during parade scenes or teaching Channing Tatum how to fold a flag at a funeral, he was always ready and available. The male cast members got to know him better than they may have wanted at boot camp, where they slept in cots trimmed with mosquito netting, endured classes on and drills with weapons, firing 6,000 rounds during the course of their training. They began their day at 5:30 am with reveille and by 6:30 am, they were well into their rigorous military style PT, all courtesy of Sgt. Major Dever.

“It was like a total immersion system for the actors,” recalls Peirce of boot camp and the extensive research material she provided to them before filming began. “I shared with them hours and hours of interviews I’d done with soldiers as well as live footage from Iraq shot by soldiers who were there.”

Timothy Olyphant joined the cast as Brandon’s CO Boot Miller and he consulted with Sgt. Major Jim Dever about his character. “I asked him a few questions, but he was running around all day commanding the extras. So I thought, ‘you know what, I’ll do what he’s doing,’” Olyphant laughs.

Victor Rasuk was cast in the role of Rico Rodriguez, a role that required the application of special make-up and extensive prosthetics, including contact lenses that blinded Rasuk, to convey the horrible injuries Rico suffers in battle. Rasuk elected to keep the contact lenses in during his scenes and the constricting prosthetics caused him to limp; often, Peirce or Phillippe would guide him to his mark on set or towards a chair in between takes, much as they would have done to his severely wounded character.

“For me, the prosthetics helped me with the character. My arm was bound behind my back and it hurt like hell, so I incorporated that into my character, as part of his literal and emotional pain. I wanted to keep the contacts in because I honestly felt like I was in the dark, as Rico would. I couldn’t see anything. When the cast and crew walked around me, I didn’t know where anyone was or who they were, I saw only shadows. It was very helpful,” Rasuk says. who they were, I saw only shadows.

Rasuk adds that Peirce understood his desire to use the prosthetics but her guidance helped him navigate not just his temporary blindness but also his acting. “At first, the contacts were making me really cerebral, I spent too much time inside my head, so my acting was too forced. Kim stopped everything; she took me aside and gave me a heart-to-heart, not just like a director to an actor, but like an actor to an actor, she really understood the process. She takes such good care of her actors and I really appreciated that, ” Rasuk says.

Rico recuperates at an Army Medical Center, for which the production used the Austin State School, home to about 436 people with developmental disabilities. Several of the school’s buildings had fallen into disrepair, including the ones chosen for Rico’s scenes. The art and set decoration departments revamped several interiors, which included the painstaking and costly business of removing asbestos. The production donated the freshly painted, restored facilities to the State School, which intended to turn them into art rooms for the residents.

Far from the plains and small towns of Texas, the cast and crew traveled to Morocco where they joined forces with additional crew from Czechoslovakia, Spain and Morocco to film a pivotal battle scene which is set in Iraq early in the film.

“In the film, our key characters have served together in Afghanistan and Iraq for a while, and have remained relatively unscathed. They are on a final mission before returning home, a mission which alters their destiny,” explains Peirce. “They encounter a roadblock, and are drawn into an ambush resulting in some severe casualties. In order to save his remaining comrades, Sgt. Brandon King must make agonizing decisions—decisions which will haunt him long after he has returned home.” ome.”

The choice of Morocco as the location for shooting this important Iraq- based battle proved to be a fortuitous one. “Morocco is amazing and the people were so warm and welcoming,” recalls Peirce of the experience. “For me, there was a whole layer of sensitivity regarding our company coming into this Islamic country and into their space. The scene we shot involved a military raid, so when we were shooting in Marrakech, we were going into the actual homes of these people, not a set on some soundstage. It was very humbling being over there—I was so impressed with their sense of community and their hospitality toward us.”

“We were careful to lay out the specifics of the scene when working with Moroccan officials to organize the shoot,” adds producer Gregory Goodman. “We were very sensitive to the fact that we were essentially depicting the invasion of a neighborhood, so we worked closely with our contacts there early on in terms of scene requirements, logistics and security, so they would know what to expect during our time there. The King of Morocco, the officials and the community of Marrakech were all incredibly helpful and cooperative—It was a terrific experience.”

The filmmakers hope that the characters and the story of “Stop-Loss” will resonate with audiences. For Phillippe, “Stop-Loss” is essentially a personal tale. “I see it as a unique set of circumstances, not a sweeping indictment of any group, or of the military, or the Administration,” he says. “Although it does say something about the situation we’re in, what’s at the heart of the drama is what happens to these guys when they come back home and can’t cope. One guy’s wife leaves him and he’s got a drinking problem. The other guy is having posttraumatic stress disorder…it’s about the ramifications of war, and the sorrow that can be reaped.”

“This movie is definitely pro-soldier,” says Peirce. “It may not be pro the Stop-Loss policy. But we have tried to honor and to show with great compassion and understanding the unique experience of these brave men and women and the effect that war has, not only on them, but on their families, friends and everyone around them.”

Stop-Loss (2008)

Directed by: Kimberly Peirce

Starring: Ryan Phillippe, Abbie Cornish, Channing Tatum, Joseph Gordon-Levitt, Ciarán Hinds, Timothy Olyphant, Victor Rasuk, Rob Brown, Linda Emond, Mamie Gummer

Screenplay by: Mark Richard, Kimberly Peirce

Production Design by: David Wasco, Judy Becker

Cinematography by: Chris Menges

Film Editing by: Claire Simpson

Costume Design by: Marlene Stewart

Set Decoration by: Sandy Reynolds-Wasco

Art Direction by: Peter Borck

Music by: John Powell

MPAA Rating: R for graphic violence and pervasive language.

Distributed by: Paramount Pictures

Release Date: March 28, 2008

Views: 101