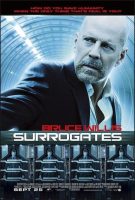

Sending “Surrogates” to the Big Screen

Surrogates Movie Trailer. Producer Max Handelman, a lifelong comic book aficionado, optioned the graphic novel from Venditti. He found the story’s themes compelling. “The story really moves along at a great pace and allows you to imagine something that could impact our society someday. Are we all going to have surrogates? Probably not. But it’s a metaphor for our society’s increasing reliance on technology and increasingly virtual communication.”

Handelman brought the comic to a college friend, veteran producer Todd Lieberman, who is partnered with longtime industry producer and studio executive David Hoberman at Mandeville Films. “I was looking for something with an edge, a film noir-type story and I found that in Robert’s story,” says Lieberman. “The movie starts with two really attractive people outside of a club. All of the sudden, some guy approaches and they fall dead. You have no idea what’s going on. In comes a detective, Bruce Willis’ character, and his partner. And you realize pretty quickly that we’re living in a world that’s not our world.

“The two people who’ve been killed are actually surrogates,” continues Lieberman. “Not only are the surrogates getting destroyed, but the people controlling them at home have been murdered, which is something that’s never happened in the history of surrogacy. The entire world of surrogates is at risk because the fail-safe of not harming the user is the cornerstone of the technology.”

Jonathan Mostow agreed to direct the film; his longtime writing partners, John Brancato and Michael Ferris (“Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines,” the 1991 telefilm, “Flight of Black Angel”), were tapped to tackle the script, marking a professional reunion for the trio of Harvard University alums.

Making “Surrogates” A Reality

“SURROGATES” marked a homecoming of sorts for director Mostow, a Connecticut native who graduated from Harvard University 25 years ago. In addition to mounting the film in several neighborhoods around Boston—the Leather District, the Financial District, the South End, Chestnut Hill, and the home of his alma mater, Cambridge, among them—Mostow also filmed in such Boston suburbs as Worcester, home to the FBI headquarters in the city’s shuttered downtown courthouse; Taunton—its abandoned Dever State Hospital mental institution doubled for The Prophet’s Reservation commune; and Hopedale, where the former Draper Mill loom factory was the site for the film’s more climactic moments.

Says producer Hoberman, “The interesting thing about Boston, from a filmmaker’s point of view, are these historic structures and buildings that were built in the 1800s. It has this classic American brick-and-stone architecture alongside these glass monoliths. And the one thing Boston’s done better than any city in the country is have it fit together. Our story is not really futuristic, but sort of in the present. And Boston, in its architecture, gives you that sense of both past and future, and we rode that line with it.”

To create this imaginative world pitting technology against humanity, Mostow recruited top filmmaking veterans, including production designer Jeff Mann and his art department, notably set decorator Fainche MacCarthy.

“One of the things I really liked about this movie was the wide range of looks and sets and locations and environments that we created and visited,” Mostow says. “In terms of all the looks and designs, we spent six months before we ever started building, just talking and conceptualizing, making sure that things were based in logic, which was satisfying both for myself and for our production designer, Jeff Mann. A lot of thought went into this, and a lot of really talented people did some great work.”

“This world is thrilling and interesting and visceral,” says Mann. “The graphic novel is a very moody, dark story set in this futuristic environment. In the movie, we set the story in a kind of parallel world. This technology of surrogacy is extremely advanced, but the surrogates in our story are tools. Their operators are absolutely responsible for the actions of this machine, just like you would do to any other machine.”

Mann designed several large set builds for the film, notably the DMZ habitat where a renegade band of humans have taken refuge from this technological world devoid of humanity and sensitivity.

There, one of the story’s central action sequences takes place in a mammoth maze of rusted, rotting shipping containers piled atop each other like huge building blocks rattled in a massive earthquake. An apocalyptic wasteland framed against a rotting loom factory abandoned three decades ago that provided a stark backdrop to a society that Mann calls “extremely bleak.” “The DMZ zone is a trashladen slum,” says Mann. “It’s a kind of commerce area for the Dreads, where they’re recycling or stripping copper wire. They use these things to barter with in the surrogate world for the necessities they can’t manifest for themselves in order to live in their isolated state.”

“The DMZ is this kind of war zone that surrounds the Reservation where the Dreads live and disconnect from society,” says Mostow. “It was full of burned-out vehicles and parts where these people try to make their living by manufacturing items that they can live on. This, along with the Reservation, were two sets in the movie that help make for a different experience for the audience.”

In stark contrast to this post-apocalyptic backdrop was the serenity of the Dever State Hospital, a sprawling, abandoned medical campus in far south-suburban Taunton that became the perfect setting for The Prophet’s isolated Reservation commune where the Dreads “sort of live life the way we probably did in the ’30s and ’40s,” says Hoberman. “A simpler life, without any technology, where humans farm their own food.”

“It had this urban quality to it that felt kind of city adjacent,” adds Mann. “It had an overgrown feeling as if reclaimed by nature. We put solar cells on the roofs and created these cisterns to affect the reclaiming of rainwater. We also planted vegetable gardens like public green spaces.”

The place where surrogates actually went for their own robotic facelifts was fabricated in Boston’s downtown Leather District in a chair manufacturing plant that became Maggie’s beauty salon in the film.

“Maggie is a beautician and the beauty in this world involves technology,” Rosamund Pike says about her character. “My beauty shop is almost like an auto-body shop. We’re doing blasting and sanding—industrial beauty is what we call it.”

Fainche MacCarthy’s crew dressed the set with power tools and belt sanders—all with dainty pink flowered handles. “There’s a scene where Rosamund has this beautiful woman who’s come in to get a face replacement,” prosthetic makeup artist Howard Berger says. “We built a replica of the actress that had a face that you could peel off. It was a very thin silicone face that fit over an endoskull over this upper torso of the actress. It’s a seamless blend of the actress talking, while the face is being pulled off, revealing the robot’s endo-skull underneath. Mark Stetson’s visual effects department pulled it all together.”

One of Mann’s eye-catching creations included the “stim chair,” the device from which humans neurally operate their robotic doubles. “The stim chairs were a challenge because I didn’t want them to look too dental,” Mann says. “It’s a comfortable, exposed lounge chair with these sensor devices that are supposed to articulate nerve reactions and other muscle stimulus.”

“The initial concept in the script for the stim chair was this very comfortable seat where you were attached to wires and electrodes,” Mostow adds. “We didn’t want something that felt claustrophobic, so I came up with the idea that essentially you are in something like a massage chair—which already creates a sense of relaxation. And there are lasers reading your skin temperature and reading your body movements and neural impulses. The only thing you have to wear is a very light headset that’s modeled on something like a Bluetooth. The idea was to create something one wouldn’t mind sitting in for 16 hours a day.”

To complement the stim chair, Mann also fabricated another key set piece—the charging cradle. “When you buy your surrogate, it’s shipped to you in this dual-purpose container that’s both the shipping container and the charging cradle for it,” Mostow says. “So, at the end of the day, you come home and you back into your charging cradle and plug in to recharge.”

The actual robotic look of the main cast and hundreds of extras appearing in the film came to life through the combined efforts of the film’s two makeup departments—the key makeup under the guidance of Oscar®-winner Jeff Dawn (“Terminator 2: Judgment Day”), and the special prosthetic designs courtesy of another Oscar winner, Berger (“The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe”). Because most of the main cast portrays two or more versions of their characters, Dawn and Berger utilized their many years of trickery to distinguish between the perfect surrogates and their rather imperfect human counterparts.

“The challenge for makeup and hair on this film from day one was determining what differentiates a human from a surrogate,” says Dawn. “Surrogates—are they plastic? Are they hyper real? Are they better looking than normal attractive people? The challenge was to make people who are already good looking look spectacular in every shot.

“The idea of surrogates touches on vanity that we all have, especially in this industry,” continues Dawn. “It touches on the technological advancements that we’ve made in the last few decades. You combine the two and you come up with a seemingly wonderful idea—the perfect man. I’ll make myself younger or taller or better looking.”

Dawn says that Willis had no trouble accepting himself in his own skin—even when the artisans added less-than-ideal details. “The human Greer character is a little older, a little rougher, a little more wrinkled,” says Dawn. “And Bruce was very good about that. When I needed to add a little age, some wrinkles, a salt-and-pepper beard, he was game for all of that. Now the surrogate Bruce had to be perfect, which we accomplished using a full head of blonde hair and these blonde eyebrows.”

Prosthetic makeup creator Berger needed to decipher the evolution of surrogates in his approach to designing a wide assortment of makeup applications and animatronic puppets for the film.

“There were a tremendous amount of challenges in trying to figure out how surrogates evolved,” he says. “I sat down with Jeff Mann and Jonathan to work out ideas, which presented us with many questions. Are they more robotic? Are they made of plastic or metal? Are their skins silicone? Are they something organic? Are they carbon fiber? The most important thing was what their endoskeletons were like. What’s inside of a surrogate? They’re all synthetic, made out of plastics and carbon fiber. Completely mechanical. Robots.”

Some of Berger’s unique designs included the crucified corpse of the surrogate Greer after it’s destroyed; shotgun wounds that graphically reveal the mechanical innards of the robotic doubles—KY jelly and green food coloring worked well as the hydraulic fluid that circulates through the surrogates; and eight animatronic “drone” puppets that operate the surveillance monitors inside FBI headquarters.

Casting Boston as the locale of this parallel reality created a challenge for the film’s visual effects gurus, here under the supervision of Oscar® winner (and three-time nominee) Mark Stetson. The film marked a homecoming for Stetson (honored in 2006 as one of Hollywood’s “Digital 50” content creators by the Hollywood Reporter and the P.G.A.), another Massachusetts native among the crew.

Stetson, who began his career 30 years ago, calls his role on “SURROGATES” a supporting one. “Our job was to help integrate the concept of surrogates into the everyday reality portrayed in the film. Because the movie takes place in the present, we tried to integrate some of the more advanced technologies in the story into everyday scenes to make everything look real.”

Making a perfect robotic version of a high-profile actor was a tricky business, he says. “The differences between the surrogate and its human owner/operator were established primarily with costume and makeup, live on the set,” Stetson says. “We enhanced those differences with VFX technologies beyond the limit of practical stage techniques by using a combination of 2D compositing and 3D CG techniques.”

Mostow also called on veteran cinematographer Oliver Wood (“The Bourne” trilogy), the longtime journeyman whose lighting and camera work enhanced the claustrophobic atmosphere of Mostow’s 2000 Oscar-winning WWII thriller, “U-571.” Emmy-winning costume designer April Ferry (HBO’s “Rome”) returned for her third project with the director, one in which she created dual worlds as illustrated by a combination of store-bought threads and custom-made clothing which vividly distinguished the state of surrogates versus that of humans among the film’s cast. The director also tapped veteran film editor Kevin Stitt, who cut Mostow’s big screen debut, “Breakdown,” over a decade ago.

Surrogates (2009)

Directed by: Jonathan Mostow

Starring by: Bruce Willis, Ving Rhames, Radha Mitchell, Rosamund Pike, Ned Vaughn, James Ginty, Boris Kodjoe, Helena Mattsson, Jeffrey De Serrano, Danny F Smith, Brian A. Parrish

Screenplay by: Michael Ferris, John Brancat

Production Design by: Jeff Mann

Cinematography by: Oliver Wood

Film Editing by: Kevin Stitt, Barry Zetlin

Costume Design by: April Ferry

Set Decoration by: Debbie Cutler, Basia Goszczynska

Art Direction by: Tom Reta, Dan Webster

Music by: Richard Marvin

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for intense sequences of violence, disturbing images, language, sexuality and a drug-related scene.

Distributed by: Buena Vista Pictures

Release Date: September. 25, 2009

Views: 177