Taglines: Life was too small to contain her…

Sylvia movie storyline. Born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1932, Sylvia Plath developed a precocious talent as a writer, publishing her first poem when she was only eight years old. That same year, tragedy introduced itself into her life as Plath was forced to confront the unexpected death of her father. In 1950, she began studying at Smith College on a literary scholarship, and while she was an outstanding student, she also began suffering from bouts of extreme depression.

Following her junior year, she attempted suicide for the first time. Plath survived, and, in 1955, she was granted a Fulbright Scholarship to study in England at the University of Cambridge. While in Great Britain, Plath met Ted Hughes, a respected author, who would later become the British Poet Laureate. The two fell in love and married in 1956.

Marriage, family, and a growing reputation as an important poet nonetheless failed to bring Plath happiness. She became increasingly fascinated with death, a highly visible theme in her later poetry and her sole novel, The Bell Jar (1963). After Hughes left her for another woman, Plath’s depression went into a tailspin from which she never recovered. She killed herself at age 30.

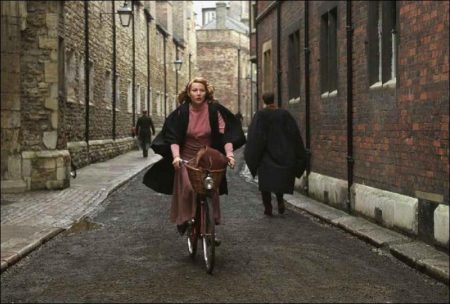

Sylvia is a British biographical drama film directed by Christine Jeffs and starring Gwyneth Paltrow, Daniel Craig, Jared Harris, and Michael Gambon. It tells the true story of the romance between prominent poets Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes. The film begins with their meeting at Cambridge in 1956 and ends with Sylvia Plath’s suicide in 1963. Filming took place between October 2002 and February 2003. Much of the film was shot in and around the New Zealand city of Dunedin, with the University of Otago serving to represent Cambridge.

Film Review for Sylvia

‘Fame will come. Fame especially for you. Fame cannot be avoided. And when it comes You will have paid for it with your happiness, Your husband and your life.’ So (perhaps) the spirit of the Ouija board whispered to Sylvia Plath one evening when she and Ted Hughes were spelling out their futures and she suddenly refused to continue.

Hughes uses the speculation to close his poem “Ouija” in Birthday Letters, the book of poetry he wrote about his relationship with Plath. It was started after her suicide in 1963 and published after his death in 1998. It broke his silence about Sylvia, which persisted during years when the Plath industry all but condemned him of murder.

But if there was ever a woman who seemed headed for suicide with or without this husband or any other, that woman must have been Plath, and there is a scene in “Sylvia” where her mother warns Hughes of that, not quite in so many words. “The woman is perfected,” Plath wrote in a poem named “Edge.” “Her dead body wears the smile of accomplishment…” Of course it is foolhardy to snatch words from a poem and apply them to a life as if they make a neat fit, but “Edge” was her last poem, written on Feb. 5, 1963, and six days later she left out bread and milk for her children, sealed their room to protect them and put her head in the gas oven.

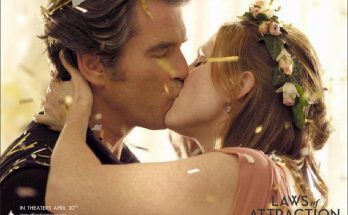

Christine Jeffs’ “Sylvia” is the story of the short life of Plath (1932-1963), an American who came as a student to Cambridge, met the young poet Ted Hughes at a party, was kissed by him before the evening had ended, and famously bit his cheek, drawing blood. It was not merely love at first sight, but passion, and the passion continued as they moved back to Massachusetts, where she was from, and where he taught.

Then back to England, and to a lonely cottage in the country, and to the birth of their children, and to her (correct) suspicion that he was having an affair, and to their separation, and to Feb. 11, 1963. He was famous before she was, but the posthumous publication of Ariel, her final book of poems, brought greater fame to her. In the simplistic accounting which governs such matters, her death was blamed on his adultery, and in the 35 years left to him, he lived with that blame.

Hughes became Britain’s poet laureate. He married the woman he was having the affair with (she died a suicide, too). He burned one of Plath’s journals — he didn’t want the children to see it, he said — and was blamed for covering up an indictment of himself. He edited her poetry. He saw her novel The Bell Jar to press, and kept his silence.

Birthday Letters is all he had to write about her. When you read the book you can feel his love, frustration, guilt, anger, sense of futility. When you read her poetry, you experience the clear, immediate voice of a great poet more fascinated by death than life. “Somebody’s done for,” she wrote in the last line of “Death & Co.” (Nov. 14, 1962), and although that line follows bitter lines that are presumably about Hughes, there is no sense that he’s done for. It’s her.

A movie about their lives was probably inevitable. It will be bracketed with “Iris,” the 2001 film about the British novelist Iris Murdoch, who died of Alzheimer’s. I deplored the way that movie made so much of Iris the wild young thing and Iris the tragic Alzheimer’s victim, and left out the middle Iris who was a great novelist — whose work made her life worth filming in the first place. I am not so bothered by the way “Sylvia” focuses on the poet’s neurosis, because her life and her work were so entwined.

Dying/Is an art, like everything else/I do it exceptionally well. … she wrote.

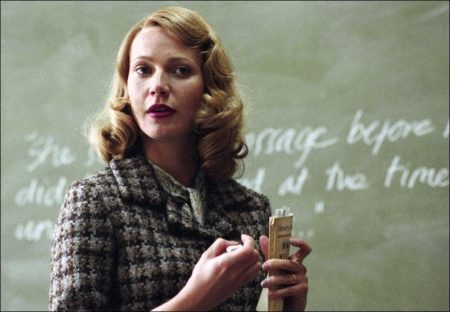

The film stars Gwyneth Paltrow as Sylvia and Daniel Craig as Ted. They are well cast, not merely because they look something like the originals but because they sound like workers who live with words and value them; there’s a scene where they hurl quotations at each other, and it sounds like they know what they’re doing. Paltrow’s great feat is to underplay her character’s death wish. There was madness in Sylvia Plath, but of a sad, interior sort, and one of the film’s accomplishments is to show in a subtle way how it was so difficult for Hughes to live with her.

The movie doesn’t pump up the volume. Yes, she does extreme things, like burning his papers and wrecking his office, but he does extreme things, too. Adultery is an extreme thing. In this consider the scene where Hughes meets Mrs. Plath for the first time. Played by Blythe Danner (Paltrow’s mother), Aurelia tells her daughter’s lover that Sylvia had tried to kill herself and was a person who was capable of getting it right one of these times.

It is difficult to portray a writer’s life. “Sylvia” handles that by incorporating a good deal of actual poetry into the movie, read by or to the characters, or in voice-over. It also captures the time of their lives; they were young in the 1950s, and that was another world. England gloomed through postwar poverty, there were shortages of everything, red wine and candles made you a bohemian, poets were still considered extremely important, and Freud was being ported wholesale into literature; poets took their neuroses as their subjects. Literary criticism was taken seriously, because it was written in English that could be understood and had not yet imploded into academic puzzle-making. To be good in that time was to be very good, and Plath and Hughes both were first-rate.

There are two questions the movie dodges. We don’t know the precise nature of Hughes’ cheating, and we don’t understand how Plath felt about the children she was leaving behind — why she thought it was acceptable to leave them. The second question has no answer. The answer to the first is supplied by Hughes’ critics, who accuse him of womanizing, but the film dilutes that with the suggestion that he simply could not stay in the same house any longer with Sylvia.

Imagine a hypothetical moviegoer who has not heard of Plath or Hughes or read any of their poetry. That would include almost everyone at the multiplex. Is there anything in “Sylvia” for them? Yes, in a way: A glimpse of literary lives at a time when they were more central than they are now, a touching performance by Paltrow, and a portrait of a depressive.

But for those who have read the poets and are curious about their lives, “Sylvia” provides illustrations for the biographies we carry in our minds. We see the milieu, the striving, the poverty, the passion, and we hear the poetry, and in the way Paltrow’s performance allows Sylvia to grow subtly distant from her daily life, we sense the approach of the end. There is not even the feeling that we are intruding, because the poems of these two poets violated their privacy in a manner both thorough and brutal.

Sylvia (2003)

Directed by: Christine Jeffs

Starring: Gwyneth Paltrow, Daniel Craig, Jared Harris, Michael Gambon, Blythe Danner, Lucy Davenport, Jeremy Fowlds, Sarah Guyler, Jared Harris, Theresa Healey

Screenplay by: John Brownlow

Production Design by: Maria Djurkovic

Cinematography by: John Toon

Film Editing by: Tariq Anwar

Costume Design by: Sandy Powell

Set Decoration by: Philippa Hart

Art Direction by: Jane Cecchi, Joanna Foley, John Hill, Ken Turner

Music by: Gabriel Yared

MPAA Rating: R for sexuality / nudity and language.

Distributed by: Focus Features

Release Date: october 17, 2003

Views: 99