The Chronicles of Riddick Movie Trailer. In 2000, David Twohy’s Pitch Black had audiences and critics alike doing double-takes with a “where-did-that-come-from?” buzz. The modestly budgeted science fiction thriller was a compelling reminder that genre films could have brains to match the brawn…in this specific case, the brawn of Riddick, the film’s fascinating anti-hero, portrayed by Vin Diesel, at that time a new discovery.

“Pitch Black was meant to be a commercial film not unfamiliar in its setting or context,” notes Twohy, “but unexpected in its depth of character. I wanted to play with reversal of expectation, so that the `bad guy’ redeems himself. I wanted to play out a good morality play at the heart of a commercial science fiction horror film.”

With Pitch Black, Twohy and Diesel created an anti-hero for our time in Riddick, whom the actor calls “a seemingly nefarious character who ends up being your only hope. Riddick lives within the realm of neutrality. These least likely of heroes sometimes take on a cult status in the science fiction community.”

Riddick is the antithesis of the staunchly upright movie hero. According to Diesel, “Riddick, who has been counted out, given up on, overlooked and misrepresented, winds up being the one you are praying succeeds in saving you and everyone else in the universe.”

Executive producer George Zakk, Vin Diesel’s associate in their company, One Race Films, recalls the groundswell of grass roots approval that developed for the character of Riddick in the wake of the release of Pitch Black. “When we hit the road promoting the film, there were always huge crowds waiting. Riddick was an anti-hero that people just related to. They would say, `This guy’s cool. He doesn’t play by the rules. He doesn’t give a damn about anybody or anything.’ But by the end of the film, he’s no longer a `bad guy.’ There’s an ambiguity to Riddick that audiences respond to and find intriguing. Riddick is the most unlikely of heroes. He’s an interesting character, because he knows that there’s something special about himself, but he’s reticent to accept the responsibility that may come with that.”

How do you make an anti-hero? “You let him evolve into it,” responds Twohy. “It didn’t hurt that for the first half-hour of Pitch Black, Riddick doesn’t speak, which only heightened his charisma. And when he does speak, he is selective with his words. In Pitch Black, Riddick evolved from a killer to an anti-hero, and he retains that anti-hero status at the beginning of the new movie. The Chronicles of Riddick is more about understanding who he really is, and that he is no small player in the universe. His loner status is over.”

Diesel was also excited to explore previously unexplored aspects of the character. “In Chronicles, you can invest in Riddick’s development, become a part of that. The film takes you, step-by-step, through the process of watching him understand the significance and value of his life. It’s really his evolution, watching an anti-hero re-join the human race.”

“We actually started to think about a second Riddick movie when we were in post-production on Pitch Black,” Twohy recalls, “and I knew the trap that other sequels had fallen into, replaying the same thing over and over again. I said that the key to a sequel is not to do the expected. Don’t go back to the same planet, don’t meet the same creatures and don’t even let it be a creature movie. We actually changed genres from horror to science fiction action-adventure. We wanted a metamorphosis rather than a re-run.”

Pitch Black’s reception and success as a home-video title infused both its creator and star with the hope that they could return to the world of Riddick… but this time, on a larger scale, building a new, mythological, action-adventure world around him, populated by equally fascinating characters. The Chronicles of Riddick would be a story rich in complex characters set in a compelling and seductive, imaginary world, peopled with a planetary array of warring races and competing agendas. Twohy and Diesel’s mandate was to endow Riddick with new challenges, an ensemble setting, huge action set pieces and greater adventures.

From their experiences working together on Pitch Black, Diesel and Twohy knew that together, they created a winning combination of action, fantasy know-how and science fiction smarts. Luckily, Twohy had just finished directing and writing the supernatural thriller Below, and was available to return to the Riddick playing board. And like Diesel, he was also looking “to paint on a bigger canvas” with his screenplay for the continuation of Riddick’s adventures, The Chronicles of Riddick.

“David’s script totally blew everyone away,” recalls producer Scott Kroopf. “We all knew we had something pretty special. I think people were kind of expecting him to do just a bigger version of Pitch Black, but were excited that David went so far beyond that, dreaming up worlds and universes. The Chronicles of Riddick does relate the further adventures of Riddick, but it’s also an exploration of a whole world with extraordinary elements and a stand-alone story.

“Pitch Black fans will certainly see things paid off in the new movie,” continues Kroopf, “but it’s not required that you’ve seen the first film, because the characters have their own introductions.”

Inventing Universes: Visualizing The Chronicles of Riddick

With a significantly larger budget to work with-and a huge canvas in which to free the imaginations of all involved-Twohy began to put together a dream team of conceptual designers such as Matt Codd, Daren Dochterman, James Oxford and Brian Murray to begin sketching the world of The Chronicles of Riddick. Soon thereafter, Twohy secured the considerable talents of production designer Holger Gross, whose previous foray into the world of motion picture science fiction was Roland Emmerich’s well-regarded Stargate. Gross, supervising art director Kevin Ishioka and their huge team had one mandate from Twohy: “If we’ve seen it before, throw it away.”

The artists focused their efforts on defining three key looks for the film: the environments of the Necromongers, which primarily included their command mothership, the Basilica, and the worlds vanquished by their campaign; the planet Crematoria-hellish in its temperature extremes of 700° by day and -300° at night-and its subterranean prison, the Slam; and Planet Helion, home to an advanced, halcyon society that prospers by capturing, storing, trading and distributing light to far-flung worlds. Gross was determined to create physical elements for the film that were not specifically wedded to the future, but could also invoke the past.

Awash in warm tones, the cities of Helion vary in their architectural style to reflect the planet’s multicultural face, and mix historical and modern elements to allude to the planet’s immigrant quality and progressive outlook. The inhabitants of Helion vary in their looks and garments, but all within a palette of earthy spice colors accented with turquoises and azure blues. And, as a reflection of Helion’s main export and the wealth it brings, makeup artist Victoria Down “warmed everyone up, gave them a glow. These are peaceful, happy, wealthy people.”

If Helion is heaven, then the Slam is pure hell. As this is a for-profit prison, situated beneath the surface of an inhospitable planet and run by mobsters, the design team quickly realized that the key to creating the Slam lay in recognizing the prison not as a building imposed upon the landscape, but as a natural space that had been modified-as cheaply as possible-for use as a prison. The result is a 200 foot lava tube crudely partitioned into cells, here and there destroyed by continuous volcanic activity, filled with exposed wiring and massive air vents, covered with a film of volcanic dust and clearly lacking creature comforts, including adequate plumbing.

In stark contrast both to the cheerful world of Helion and the primitiveness of the Slam, the Necromongers are the epitome of evil sophistication…and also the toughest challenge for Holger Gross and his conceptual artists. Deciding upon a look for the Necros-that integrated elements of their military prowess, ideology and lifestyle into a scheme that was visually exciting without succumbing to stereotypes-was not an easy task. After much brainstorming amongst the group, Gross found his answer in the early Baroque architecture of 17th century Central Europe.

Huge, detailed, elegant yet heavy, punctuated with dark metal finishes, Gross calls the Necro world “twisted Baroque, if you will… a cross between fascism and theocracy, very religious and aesthetic in terms of architectural detail, yet at the same time cold and evil, but very powerful. Finally, we developed a style we called `Necro-Baroque.’”

Based on elliptic shapes, the adaptation of the Baroque style employed by Gross also created the illusion of constant movement. Everything is curved and non-directional, so that buildings appear to alter as the camera moves. This, of course, created serious construction challenges. “It would not be easy to build,” admits Gross. “There would be many struggles finding the shape, especially for technical pieces like the spacecraft and weaponry. The Necros are living in spaceships, they’re very technologically advanced, so one has to tweak and shift without losing the Necro-Baroque feeling.”

The art department under Gross and Ishioka consisted of seven illustrators, 10 set designers, two art directors and, for the prop department, two more conceptual artists. Models were made of all of the sets, as well as the crafts. “David Twohy was involved with every aspect of design,” relates Ishioka. “He approved everything, and that ensured an overriding, homogenous vision.”

The Chronicles of Riddick (2004)

Directed by: David Twohy

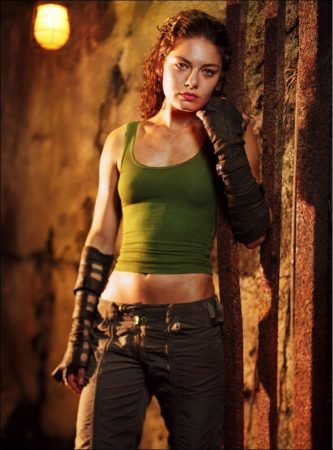

Starring: Vin Diesel, Keith David, Thandie Newton, Karl Urban, Alexa Davalos, Judi Dench. Colm Feore, Linus Roache, Keith David, Christina Cox, Terry Chen

Screenplay by: David Twohy

Production Design by: Holger Gross

Cinematography by: Hugh Johnson

Film Editing by: Tracy Adams, Martin Hunter, Dennis Virkler

Costume Design by: Michael Dennison, Ellen Mirojnick

Set Decoration by: Peter Lando

Art Direction by: Kevin Ishioka, Mark W. Mansbridge, Sandi Tanaka

Music by: Graeme Revell

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for intense sequences of violent action and some language.

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Release Date: June 11, 2004

Views: 146