About the Film

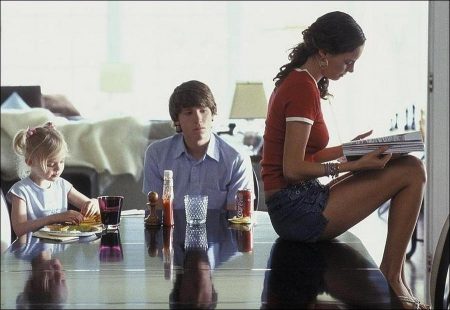

The Door in the Floor tells a tale of love and sexuality, of richly layered characters who experience both revivifying liberation and humbling emotional reversals of fortune. For those who came together to make the film, their aesthetic ties to it reveal the material’s very personal resonance.

Writer / director Tod Williams says, “It’s about how love is defined by its shadow – loss.”

Producer Ted Hope states that the film is about “the complexities of life.”

Actor Jeff Bridges sees it as “a wonderful combination of tragedy and comedy.”

Actress Kim Basinger sees the film as being “about people brought together for all the wrong reasons and being forced into the depths of truth.”

Author John Irving comments, “I think one of the most interesting things in storytelling is to see how people get over things; how they recover, or don’t recover, from what they lose.”

The first part of Irving’s best-selling novel A Widow for One Year has been brought to the screen through a unique creative alliance encompassing dedicated independent filmmakers, the celebrated author himself, and a committed troupe of actors. “It’s extremely gratifying,” states the author. “Tod Williams’ screenplay is the most word-for-word faithful translation to film of any of the adaptations written from my novels. But he has also made his own film. This is excellent work.”

The process by which A Widow for One Year became The Door in the Floor spanned several years. Casting director Ann Goulder first brought writer/director Tod Williams to the attention of producers Ted Hope and Anne Carey in 1998. At the time, Williams needed financial and logistical help to finish his debut feature, The Adventures of Sebastian Cole. His new acquaintances contributed an Avid editing system and space, and became friends and collaborators.

Williams also made time to read the [then-] new John Irving novel, A Widow for One Year. “I generally read his books as soon as they come out,” Williams states. “His novels are always big, intense emotional experiences. As a writer, his narrative techniques, depth of character, and blend of humor and truth represent a mark of excellence to which I aspire.

“I felt a personal connection to all three characters, who are selfless and selfish at the same time. I remembered when I was like Eddie, but I had become more like Ted. I read the first 183 pages in one sitting. I was very moved – and struck at how well it would work as a movie. Making this movie was about exorcising Ted – who is less capable of the generosity that is necessary for love – from my psyche.”

One day, Carey recalls, Williams “came in and gave me a copy of John Irving’s book. He said, ‘Would you read it and tell me if you think it’s a movie.’ I did, and I said, ‘I only think the first part is a movie.’

He felt the same way and we went and talked to Ted about it – “

“ – And I said, ‘You guys are out of your mind,’” laughs Hope.

Nonetheless, Hope and Carey contacted Irving’s agent, Bob Bookman. Carey remembers Bookman being “very encouraging. He said, ‘You know, it’s not about money for John at this point. He just really wants to know who the people are who are interested in making movies out of his material.’”

Seizing the moment, Carey drafted letters from the producers and Williams (respectively) to send to Irving. Hope notes, “We worked on these letters quite a bit…probably almost as long as John spent writing the novel.”

“For three weeks,” Williams specifies. “An easy way to describe our intentions to John was to reference The Ice Storm [the 1997 film version of Rick Moody’s novel, produced by Ted Hope and James Schamus with director Ang Lee].

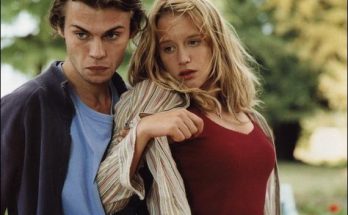

Williams had already drawn a bead on what Irving’s characters would experience on-screen. “In Eddie’s case, it’s a loss of innocence – sexual, emotional, and intellectual. For Marion, it’s the loss of her sons and then herself – of all her emotions except grief. She tries to give what’s left of herself to Eddie. And Ted has lost faith – in himself, his marriage, his talent.”

Proving again that truth can be more surprising than fiction, Irving had been Hope’s wrestling coach in high school “for about two weeks,” says the producer. “Then a book he had written had a little bit of success.

He taught me what a half-nelson was, and then three months later he was on the cover of Time.” The book was The Hotel New Hampshire. Serendipitously, in September 1999, Hope and Carey found themselves at the Toronto International Film Festival with their production of Ang Lee’s Ride With The Devil while John Irving was also there with The Cider House Rules (which he had adapted from his novel and which was directed by Lasse Hallström). Both films starred Tobey Maguire. Hope asked the young actor for a re-introduction to Irving. When it came, Irving told Hope that he had read the letters sent to him and was intrigued by the filmmakers’ intentions. He also asked to see The Adventures of Sebastian Cole, since the producers had also sent along a review of the film that called it “Irvingesque.”

Carey says, “We got John a videotape of that film; he watched it the next day and called us and invited us to his house in Vermont for the weekend.” Carey, nine months pregnant, could not make the trip, but Hope and Williams borrowed the latter’s father’s sports car and sped from New York City to Vermont.

At Irving’s house, the filmmakers discussed the planned screenplay adaptation with the author. Hope says, “John very much liked that we weren’t looking to adapt the whole novel, and that we were looking to be faithful to the tone, the greater feeling. By the time the weekend was over, John said, ‘Let’s do it. I want to give you the book.’

“He wanted to work out an arrangement where we were all in this together. Basically, he granted us a free option on the novel. It was a joint belief, as filmmakers and writers and artists, that we could find a common ground. He had tremendous faith in Tod, as we did.”

“Being able to talk to John about all of the choices I made in the adaptation, casting, and editing has been an incredible luxury,” states Williams. The author did reserve the right to input and approval on several key components of the project: “The title, the actors, and script approval. But he launched us on our way,” says Carey.

Hope adds, “John wanted to make sure that Tod got to direct the movie, that it wasn’t going to be the situation where the writer does a script that everyone loves and, because he isn’t a known director, is taken off the project.” Irving’s previous experiences with the film industry had exposed him to that all-too-familiar scenario.

“With that kind of support, we were ready for the long battle to get the film made – almost four years,” says Hope.

“His confidence in me, however mysterious, is what allowed me to see this through,” adds Williams.

It had taken over a dozen years for The Cider House Rules to get made into a movie. But John Irving, who won an Academy Award for adapting The Cider House Rules to the screen, muses that “it’s a great treat for me, to be 62 and have what feels like a new career – in addition to my day job of being a novelist. That’s where my heart is. But I get so much out of being involved in the occasional collaborative effort that it energizes me when I go back to writing novels.”

Irving feels that A Widow For One Year lends itself to the “kind of abridgement” Tod Williams has made with The Door in the Floor. “With The Cider House Rules, from the moment I finished that novel, I saw how to do it as a film. But I didn’t see a way to do A Widow for One Year as a film, because in the novel the feeling of the passage of time is as important as any major character. I had already rejected several proposals for a film. Tod’s idea to tell only the first third of the novel as a film is a much more truthful focus on what the spirit of the novel really is. I liked Tod’s idea immediately.”

Michael Corrente adds, “There’s not enough time to make a film of the whole book, to do it right as a movie. This adaptation has a wonderful beginning, middle, and end.”

Irving concurs, noting that “the novel is structured like a play in three acts. The first act has its own kind of closure. There’s a very good precedent for making a film from a long novel in this way: The Tin Drum, which was resolved in much the same way that Tod has resolved A Widow for One Year. It’s a far better idea than truncating or overcompressing a long novel, denuding it of all of its vital parts.”

“Marion is a woman who cannot only not recover from the death of her two sons, but also cannot recover sufficiently to love the one child she has. There is a sadness, a fragility to her. Everything that happens in the story happens because Ted, in a kind of callous way, has been able to move on from the death of his children. He is sympathetic in spite of himself. He and Marion are on diverging tracks, sexually and within their ability to deal with grief. For Eddie, this story is a learning experience. I feel that, from his very first treatment, Tod understood all that. He fine-tuned and revised the screenplay; he did the necessary revisions.

The Door in the Floor (2004)

Directed by: Tod Williams

Starring: Jeff Bridges, Kim Basinger, Jon Foster, Elle Fanning, Bijou Phillips, Mimi Rogers, Mike S. Ryan, Rachel Style, Libby Langdon, Amanda Posner

Screenplay by: Tod Williams

Production Design by: Thérèse DePrez

Cinematography by: Terry Stacey

Film Editing by: Affonso Gonçalves

Costume Design by: Eric Daman

Set Decoration by: Nick Evans

Art Direction by: Nicholas Lundy

Music by: Marcelo Zarvos

MPAA Rating: R for strong sexuality and graphic images, and language.

Distributed by: Focus Features

Release Date: July 14, 2004

Views: 411