Nasty Little Secrets: De Niro Uncovers the CIA

The Good Shepherd Movie Trailer. Since the early 1990s, actor / director / producer Robert De Niro has been researching the subject of what would become his second directorial effort following 1993’s acclaimed film A Bronx Tale. “Bob has always had an interest in foreign policy and the way that we gather intelligence,” relates Tribeca Films and The Good Shepherd’s producer Jane Rosenthal.

However, the Academy Award-winning actor was not interested in directing the standard fare of a spy-game fantasy. He wanted to make a film that would showcase the actual underpinnings of intelligence services and uncover how these largely anonymous men have controlled our world, at both personal and professional costs.

A friend who was aware of De Niro’s interest in the CIA introduced him to Milt Bearden, a retired 30-year veteran of the CIA who would become the lead technical advisor on the film. The former agent, who ran the CIA’s operations in Afghanistan in the mid-1980s, agreed to take De Niro across Europe and Asia on an educational journey to explore the hidden realms of intelligence gathering.

From the corners of Afghanistan to the northwest frontier of Pakistan—and off into Moscow—De Niro and Bearden traveled extensively to inform the veracity of what De Niro wanted to explore on film. In his travels with Bearden and in their research together, De Niro became privy to information with which few laypersons are entrusted.

“Bob now probably has a better feel for people in the CIA—my generation or the one before—than anybody I’ve seen that was never in the world itself,” notes Bearden. The author of several books about the CIA, Bearden explains how he is able to share closely guarded details about the United States intelligence operations without sacrifice to the men and women actively serving. “My rule is: ‘Don’t do anything that hurts anybody or puts anybody in danger, and don’t do anything that makes the job harder for anybody who’s still trying to do it,’” he shares.

De Niro’s continued fascination about intelligence gathering would gestate for several years before he was sent a copy of The Good Shepherd—an original script about the early years of the CIA by screenwriter Eric Roth—which dealt with the same issues that were intriguing the director. For the project, De Niro was offered a starring role.

The writer, whose resume includes such popular and critically celebrated works as Forrest Gump, The Insider, Ali and Munich, had created a story that wove elements of an exciting spy thriller into the everyday lives of the CIA members who created the agency. “Eric is the best writer working today,” Rosenthal compliments. “It was his look at the internal workings of the CIA that we responded to.”

Roth was interested in an earlier time period than De Niro had been researching with Bearden, but the two quickly found common ground. “I’ve been intrigued by the CIA and how it formed,” says the writer. “This agency was started with literally 17, 18 people, and has ended up with 29,000 today.”

Framing his story with key events in the CIA’s history—beginning the screenplay at the height of the OSS during World War II and closing the timeline with the CIA’s failure to accomplish its crucial mission at the Bay of Pigs in 1961—Roth’s script examined the lives of the men who formed our nation’s modern-day intelligence service.

“I researched people who went into the early years of the CIA and where they came from,” Roth says. “It was traditionally Yale and Skull and Bones.” Almost exclusively, white male Ivy Leaguers of a patrician class—considered the best and the brightest that the U.S. had to offer—ran the government arm.

In fact, this ultra-secret society counts several prominent Americans as members, including President George W. Bush; his father, former President George Bush (who headed the CIA before becoming president himself); his father’s father, Prescott Bush; as well as President Bush’s opponent in the 2004 election, John Kerry. “Some were very brave, idealistic people who decided to use it as a public service,” adds Roth.

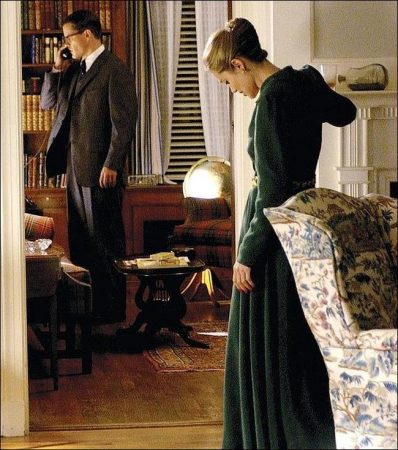

Rosenthal and De Niro responded to Roth’s protagonist, Edward Wilson, a sensitive young man who is handpicked to join the OSS in 1939. The producers understood that in telling Wilson’s story, Roth was exploring the very personal side of the agency.

“My character, as a young man, was idealistic. There were very good values that I think he was trying to protect…certain things about America that were wonderful,” reflects Roth. “He has this good-natured, good-hearted quality of justice. I wanted a character who could help write the rules for how they acted at that point, as he is the heart and soul of the agency.

“I was intrigued with what morals people have and what they’re willing to sacrifice,” Roth continues. “As I delved into it, I wanted to know more about what kind of lives these guys lived. What was his family life like, and what was life like with his children? What were his dreams for them?”

A certain amount of paranoia would seem not only justified, but inevitable, for the men who headed counterintelligence, but Roth was curious to know where it ended. “I was also interested in this whole psychological effect of entering a world where you don’t know what is right or wrong—who your friends or your enemies are,” he explains.

Earlier in its history, the United States had had no need for an intelligence organization that mined the depth of foreign information the OSS could provide…until World War II, when our leaders felt it was time for the formation of a covert agency. De Niro offers, “Our country is young at this when compared to Great Britain or other countries that have been doing it a long, long time.”

“We had two huge oceans on either side that nobody could do much about,” explains Bearden. In Europe, on the other hand, intelligence had been a vital tool throughout the years in creating and maintaining intricate alliances with nearby neighbors. With the end of WWII, however, the U.S. had a new dominant position in the world—and with it, new threats.

“The world became polarized,” explains Bearden. “It was the United States and the Soviet Union. You were lined up behind one or the other. And Khrushchev said, ‘We will bury you,’ and so we said, ‘We better figure this out.’ After 1945, that was the beginning of the American empire. An American empire without any intelligence capability didn’t make any sense.”

Roth’s Wilson, a product of these polarizing times, sees himself as both America’s conscience in dealing with the Soviet Union and as America’s protector of freedoms. As head of counterintelligence, his job is to penetrate enemy intelligence and alter our foes’ perceptions. He is also charged with learning the internal workings of KGB and what that agency knows about America.

For the filmmakers, the story became an even more important one to tell as all Americans grappled with decisions our government leaders made before the seminal events of September 11, 2001. “I think it was really in the post-September 11 world that people started to pay attention to this subject,” reflects Rosenthal. “That’s when doors opened, and real discussions began about making this kind of a movie.”

More recently, The Good Shepherd became even more topical to the filmmakers, with daily headlines about columnist Robert D. Novak’s July 2003 outing of Valerie Plame as a CIA operative after an administration source allegedly gave her name. “These are the themes, and this is our subject—this is our national security,” Rosenthal adds. “This couldn’t be any more current.”

In June 2005, Morgan Creek came on board and agreed to produce The Good Shepherd with Tribeca. Morgan Creek’s CEO, James G. Robinson, recognized Rosenthal and De Niro’s passion for the project. He succinctly offers, “This script is as good as it gets.”

Robinson was attracted to the story because he felt that it illustrated the similarities both sides share in the Cold War. “I don’t think that there was much difference between CIA and KGB,” he shares. “The difference is that when the American bureaucracy got out of line, you had remedies to strike back at a system causing harm or discomfort unfairly and illegally. They didn’t, obviously, in Russia.”

It was important to the filmmakers that the events portrayed in the film ring true to not only audiences, but the architects of American intelligence. Richard Holbrooke, former U.S. Ambassador to the U.N., former Assistant Secretary of State and career diplomat, notes of the film: “The Good Shepherd is a fictionalized version of history, which is accurate in almost every incident. But because the filmmakers are liberated from trying to be faithful to the tiny details, they’ve come a lot closer in many ways to capturing some essential truths about this extraordinary period of intelligence, counterintelligence, betrayal and espionage during the Cold War.”

That is the target for which the filmmakers were aiming. “The film is a mixture of real events and takeoffs of characters,” De Niro says. “To be locked into the factual accuracies of those events would be another kind of a movie.”

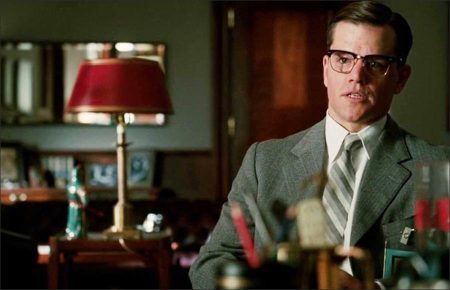

The Good Shepherd (2006)

Directed by: Robert De Niro

Starring: Matt Damon, Angelina Jolie, Robert De Niro, Martina Gedeck, John Turturro, William Hurt, Alec Baldwin, Billy Crudup, Michael Gambon, William Hurt, Timothy Hutton

Screenplay by: Eric Roth

Production Design by: Jeannine Oppewall

Costume Design by: Ann Roth

Set Decoration by: Gretchen Rau, Leslie E. Rollins, Alyssa Winter

Art Direction by: Robert Guerra

Music by: Bruce Fowler, Marcelo Zarvos

MPAA Rating: R for some violence, sexuality and language.

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Release Date: December 22, 2006

Views: 88