The Jane Austen Book Club Movie Trailer. Like a 21st century version of a Jane Austen novel, the six members of the Jane Austen Book Club live through romantic hopes and disappointments, the consolations and misunderstandings of friendship, and the infinite complications of life as social beings in a complex community. The book club members need look no further than their monthly reading and discussions to find parallels with their own lives.

Sylvia, in the midst of a divorce, has the misfortune of hosting and leading the Mansfield Park discussion; the novel is replete with dissolving alliances, romantic disappointment, marital pitfalls, and adultery. As Jocelyn says when Sylvia breaks down in tears during the book club discussion, “Reading Jane Austen is a freaking minefield.”

Jocelyn herself has an Austen counterpart: the title character of Emma is lovely, rich, vivacious, and a tirelessly meddling matchmaker who thinks she knows what everybody else needs but is foolishly blind when it comes to herself. Willfully ignoring Grigg’s interest in her, Jocelyn pushes him at Sylvia, who is too busy mourning her marital breakup to notice.

Northanger Abbey, in which the heroine is much captivated by spooky tales of Gothic melodrama, is Grigg’s novel to host for the book club. For fun, he bedecks his suburban-bland house with Halloween-style decorations, but real Gothic melodrama intrudes when the death of a character is revealed.

Ironically, the book club’s Pride and Prejudice discussion is the most fraught with heartache and anxiety. Although Pride and Prejudice is Austen’s most romantic novel, it’s laced with animosity and misunderstanding among lovers, and portrays the terrible strain of formal-dress soirees with deadly, witty accuracy.

The black-tie dinner dance that the book club attends is every bit as emotionally charged as the husband-hunting dances in the novel, and Grigg and Jocelyn bicker as poisonously as Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth Bennett. Daughters suffer through their relationships with mothers and fathers as painfully in the present-day book club as they do in the book.

Sense and Sensibility, in which mismatched engagements hamper the romantic hopes of two impoverished sisters, gives the book club members a backdrop to thrash out their discordant perspectives and attitudes. But it’s Persuasion, the last of the book club discussions, that resolves the various stories: it’s about a couple who, years before, parted bitterly, but find their way back to reconciliation and love after much hesitation and misunderstanding. In its theme of second chances, it’s a keystone for Prudie and Dean, and for Sylvia and Daniel. And in its theme of gambling on love, it inspires Jocelyn, Grigg, Allegra, and Bernadette, each in their own way.

The book club’s final romantic pairings have a satisfying resolution and rightness-just as marriage and happy endings always have the last word in Austen’s novels.

Thoughts From the Writer-Director

When John Calley asked me to read Karen Joy Fowler’s novel, The Jane Austen Book Club, I was at work on an original screenplay about a dysfunctional family of Jane Austen scholars, which I planned to direct for Sony Pictures. I had spent years immersed in Austenalia, not only reading Austen’s novels repeatedly, but also absorbing her letters and juvenilia, and making my way through various academic treatises which explored Austen’s life and work from every imaginable angle. I joked to my Sony executive that I was on the way to making the only light Hollywood comedy ever to need a bibliography appended to the credits.

However, in reading The Jane Austen Book Club, I found myself no longer in the company of sparring intellectuals. Here were ordinary people more like me; readers, seeking shelter and companionship in books. That contemporary readers have found refuge in Jane Austen’s well-ordered novels isn’t surprising, given what we’re seeking shelter from-congested traffic, ringing cell phones, squealing security wands, waiting rooms with blaring televisions. Recently I noticed that four of Austen’s six novels were for sale at the newsstand at the Seattle airport. Spend a couple of hours trapped in a terminal waiting for a flight that’s been delayed, and you’ll be only too happy to withdraw into a semi-rural English village, two centuries in the past.

When you begin to love Austen, her world doesn’t seem that antiquated. Her characters worry about money, deal with embarrassing family members, cringe at social slights, and spend more time than they should hoping to fall in love, even when the local prospects don’t seem that promising. In short, her people are just like us-but without the commute and the twelve-to-fourteen hour workday.

After finishing Karen Joy Fowler’s book, I found myself mulling over the contemporary impulse to withdraw into private refuges. The pace of our lives has turned us all into introverted extroverts, tucked up at home (for many of us home is now a workplace too); ichatting, tapping out emails, browsing networking sites and on-line bookstores, text-voting for American Idol even as our Blackberries vibrate beside the dinner plate.

In the “global village”, we have never been more available to each other- and paradoxically, never more isolated. In an era of “niche marketing”, let’s face it, we’re all in our niches. And yet here was Karen Joy Fowler’s wonderful novel, in which she describes a brave act of full-dimensional, non-virtual community. Smack in the midst of dealing with divorce, dating, bereavement and changing jobs, six people agree to read six books by Jane Austen, and then drive across town to meet in person to discuss them. Such heroism, in such an intimate story!

Adapting any book is essentially an endeavor of interpretation. The first film images that came to me as I sat with Fowler’s book became the opening montage of our movie. The story would take place where so many of us live now-at the intersection of suburbia and exurbia, next door to no one we know. At first glance our characters would be strangers we might notice briefly; people, much like ourselves, all of us in the midst of busy lives-in a hurry, on the cell phone, maybe carrying too many things; losing a parking space just when we’re late for work; this person loading groceries and wrangling kids, that person just missing the elevator; all of us beset by myriad technological irritations that Jane Austen could never have imagined.

The story would open in a setting of apparent community-a funeral for Jocelyn’s dog. Quickly we’d see: Nobody feels terribly communal. Daniel derides Jocelyn’s grief, wants to leave early. Allegra takes petty offense.

Sylvia rejects Bernadette’s suggestion that they all do something to make Jocelyn feel better. “We really should,” agrees Sylvia, then gives everyone the perfect out, “But she lives so far away.

All of Jane Austen’s novels examine order in a community, giving particular attention to an individual’s responsibility to others. In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Darcy is disliked initially because he will not provide the community service of dancing at a party where many young women are unpartnered. In Emma, the young heroine is shamed when she inadvertently insults a widow-in Austen’s rulebook, people blessed with good fortune must take care not to humiliate those of lower status. Communal order vs. one’s personal desire is a subject always lurking in the deep structures of Austen’s novels, well below the plot lines that we all love. Where else could a Jane Austen story take place except in or around a village, or in a closed social world, such as in Bath?

And in the absence of a village-say, at the anonymous intersection of suburbia and exurbia-could an Austen story even be told? What would that story look like?

I knew that in our film the character’s stories would parallel the story lines of Austen’s novels, hewing perhaps even more closely than they did in Karen Joy Fowler’s book. And yes, everyone would get each other wrong at first, as in every Austen novel, and eventually they’d find love, of course. But more importantly (at least for me), we’d see the deep subtext of Austen’s novels also played out.

When we met our characters, we’d recognize ourselves in them, living in a semblance of community, not strangers to each other, but nonetheless somehow estranged. We’d watch each person carry forward their separate storyline-but over the course of the film, we’d witness our characters fighting out their differences in book club, doubting their own ability to keep the group together, coming up against their own imperfections, and eventually we’d see these people begin to join their narratives as they figure out what it takes to come together in a meaningful way.

After I knew the shape and intention of our story, I had an overwhelming urge to write this movie as soon as possible. As I wrote and planned for the film, the Austenian idea of having to face our own imperfections was never far from my mind. In fact, during pre-production, I had a hoodie sweatshirt embroidered on the reverse, “imperfect”. When I wore it to the set the first week, a crew member jokingly objected, saying, “That’s so negative, are you saying we can’t get it perfect for you?” And our production designer Rusty Smith, quickly stepped in: “No, it’s good. It means we have freedom.” –Robin Swicord

About the Production

Like a Jane Austen heroine, director Robin Swicord and her cast and crew had to be resourceful, clever, thrifty, and amicable to make The Jane Austen Book Club-and to have fun doing it. With a fast schedule, a lean budget, and a large ensemble cast sharing so much screen time, this witty depiction of modern-day love and friendship needed a real-life atmosphere of harmony, productivity, and authenticity to look great and ring true.

“My most important task was to create an environment for these terrific actors to come together as an ensemble and make the chemistry happen,” says Swicord. “We worked very hard and fast, but we always maintained a spirit of play. Before the shoot, we did some ensemble-building theater exercises, and we named ourselves the SMUJies- Slightly Mentally Unhinged Janeites-complete with cheap T-shirts. I followed the `go with your gut’ rule in casting, and so I ended up with a set of actors who were very simpatico. This production was serious fun.”

Jimmy Smits, who has seen many a film shoot, agrees: “I haven’t felt so relaxed on a set in a long time, and I see that with all the actors. I think that will come across onscreen in a big way.”

With only six weeks to prep and thirty days to shoot, Swicord made sure that her actors had as much rehearsal time as they could squeeze in to get comfortable with their characters and each other. “Rehearsal before we began shooting was so valuable in refining the script and the blocking,” recalls Swicord.

“This screenplay didn’t go through the usual studio development process of story meetings that can sometimes flatten out a script; Sony Pictures Classics loved the original book, gave my adaptation the green light, and we were off and running. So working with the actors was the proving ground. I watched where the dialogue ran smoothly, and where actors hesitated or felt awkward, or when they seemed to need a line or a movement, and I’d pick up those cues and make adjustments. Even after we started shooting 12-hour days, I would always set aside an hour for rehearsal in the morning, knowing that we’d make up the time in richer performances and fewer takes.”

Indeed, as Kathy Baker marveled: “Robin `made her day’ every single day”-meaning that the very full daily schedule was always accomplished. “That’s a record!” A first-time feature director (though a twenty-year veteran of film production as an acclaimed screenwriter), Swicord was supported by a top-notch production team, from renowned producer John Calley, whose prolific filmography attests to a love for discovering and nurturing directorial talent, to a technical crew “that were all so game,” says Swicord. “This film was blessed with amazing filmmakers at the top of their professions. We were able to get these people-a low-budget movie on a very ambitious schedule-largely because we shot in and around Los Angeles, where the best film crews in the world like to go home at night and sleep in their own beds.”

One key crew member, however, was very far from home: Director of Photography John Toon agreed to leave his farm in New Zealand after he and Swicord clicked in the course of a four-hour phone call. “I hit the lottery that John Toon would come here and shoot this. He even agreed to stay in my house with my family to save money!”

Swicord’s goal of creating an authentic slice of life led to her choice of DP. “I wanted the look of the film to be very real-very `here’s how we live now,’ just as Jane Austen gave us such a detailed portrait of how people lived day-to-day in her time. I admired John’s camera technique in Glory Road and Sylvia, because he draws the viewer in to feel like you’re right there, an immediate observer. He invented a camera rigging that’s just a bit looser, more like human movement-barely noticeable, not handheld-jiggly, but not Steadicam-smooth either. He uses a lot of natural light, which strengthens that sense of immediacy.”

And, as John Toon notes, “What budget constraints mean is that you’re in a hurry, and you don’t get a chance to reshoot things that go wrong. So nothing does go wrong because you get one shot at making it look good.”

An anecdote related by Swicord illustrates how director and DP found the sweet spot between swift efficiency and strong performances: “We were shooting the scene of Trey and Prudie about to kiss in the car outside the school when she sees her husband approach. It’s a tense scene. John Toon and I had worked out our coverage: intimate singles from the side, and also sitting in the back seat looking over, and then going out through the windshield for the point of view shot of Dean approaching. When we shot the close-up singles inside the car, the actors were just getting warmed up, and by the time we had the cameras focused through the windshield, they were really getting good-serious chemistry. I whispered to John, “we’re going to reshoot the singles”-which meant resetting lights and cameras-and he said “no, no, we don’t go backwards,” and I said “you’re going to have to trust me on this!” And- warp speed-everybody starting resetting and we shot fast and never fell behind and I got the singles I wanted. That was a baby director’s lesson for me: don’t do the intimate singles first, always warm up with something else. Next day Tooney said “We’re gonna start with a wide shot, awright!”

Swicord forged such strongly collaborative relationships with the rest of her team. “Producer Julie Lynn can marshal armies. She had a two-year¬old while we were shooting this, and we agreed that if you can be a mother you could do anything. I needed someone who could make a little money go a long way, and who could stand by my side and be another pair of creative eyes. Plus, she’s a lawyer, so she saved us all kinds of money on legal stuff!”

Rusty Smith, the production designer, designed Swicord’s short film, The Red Coat, ten years ago. “He’s become a top big-budget designer, so he said it was refreshing to work on our modest, realistic scale, bringing the details of these characters to life on a shoestring. With an ensemble cast, the viewer has to get to know the characters very fast through their homes and clothes and surroundings, and Rusty was a genius at finding perfect locations that were true to the characters and could also be used and re-used and recycled for several different scenes. Rusty made drawings of every location, and I bought a set of Fisher-Price Little People-I let the cast pick out who they wanted to be-and moved them around to find the blocking.”

That down-to-the-details authenticity extended throughout the production. “The set decorator, Meg Everist, would do things like leave a basket of unfolded laundry on a counter that you couldn’t even see in the shot-but the actors could see it and it brought their characters’ reality to life a bit more. It’s a pet peeve of mine when movie characters live in houses and dress in clothes that are ridiculously beyond their means. I sat down with the costume designer, Johnetta Boone, and figured out where each of these characters would really shop, and that’s where Johnetta bought their clothes. If you’re a schoolteacher like Prudie, you may have style but you sure don’t have a lot of money.”

To cut The Jane Austen Book Club, Swicord-surprisingly-sought a film editor with an action-movie background. “When the book club meets and there’s bickering and colliding story lines and tension, Maryann Brandon treats it like an action scene, cutting among the quips and retorts and meaningful glances, creating momentum-we didn’t want a static bunch of talky people stuck in a room together. Her action bona fides pay off in keeping things dynamic.”

The actors, too, brought collaborative warmth and generosity to the project. “Everybody felt inspired to give extra. Emily Blunt came in to do readings with actors when we were casting Trey-I picked Kevin Zegers because he made her blush. Emily paid to have a wig made because she felt that Prudie should have that tidy French bob, and she couldn’t cut her hair because of her next commitment. We couldn’t afford a wig. Maria Bello was the first lead cast. She came in early every day to run lines. She cooked a ziti dinner for everybody. Nobody snoozed in their trailer-they all got together and rehearsed and gave it their all.”

Swicord continues: “The actors saved the day with our only real white-knuckle anxious moment: we originally cast Kathy Baker as Sky, Prudie’s mother, and Kathy said, “I’ll play Sky, but really, I was born to play Bernadette.” A light bulb went off and I switched her to Bernadette, but the actor we then cast as Sky had to drop out at the last minute. Literally two days before Sky’s scenes were scheduled to shoot, Lynn Redgrave, who was in Los Angeles with her one-woman show, agreed to do the role. It was a huge act of generosity. She played with us for two days and then rushed back to her stage show in the evenings.”

Swicord speaks warmly and admiringly of all her cast. “They’re a brainy bunch. I knew Hugh Dancy was an intellectual-he’s such a bookworm- but he’s hysterically funny, too, which I didn’t expect. I have a wonderful photo of all these actresses standing around chatting, and in the middle sits Hugh with his book, and every woman’s hand is resting lightly on his head and shoulders like he’s a beloved pet. I can’t enumerate all the wonderful things about this cast, because I’m afraid I’ll leave someone out. Amy Brenneman, Maggie Grace, Jimmy Smits, Marc Blucas-these are great actors because they’re smart and warm and generous.”

Swicord sums up the satisfying experience of directing her first feature with a quote from Jane Austen, the muse who was never far from the production’s heart: “In a letter to her niece, Austen speaks of her writing as “The little bit (two Inches wide) of Ivory on which I work with so fine a Brush, as produces little effect after much labour.” Making a movie is a world away from Jane metaphorically carving a piece of scrimshaw, but we’re really after the same thing: telling stories that reveal our lives and how we feel about love and friendship.”

About Jane Austen

December 16, 1775 to July 18, 1817

Jane Austen’s brilliantly witty, elegantly structured satirical fiction marks the transition in English literature from 18th century neo¬classicism to 19th century romanticism.

Jane Austen was born on December 16, 1775, at the rectory in the village of Steventon, near Basingstoke, in Hampshire. The seventh of eight children of the Reverend George Austen and his wife, Cassandra, she was educated mainly at home and never lived apart from her family. She had a happy childhood amongst all her brothers and the other boys who lodged with the family and whom Mr. Austen tutored. From her older sister, Cassandra, she was inseparable. To amuse themselves, the children wrote and performed plays and charades, and even as a little girl Jane was encouraged to write. The reading that she did of the books in her father’s extensive library provided material for the short satirical sketches she wrote as a girl.

At the age of 14 she wrote her first novel, Love and Freindship (sic) and then A History of England by a partial, prejudiced and ignorant Historian, together with other very amusing juvenilia. In her early twenties Jane Austen wrote the novels that were later to be re-worked and published as Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey. She also began a novel called The Watsons, which was never completed.

As a young woman Jane enjoyed dancing (an activity which features frequently in her novels) and she attended balls in many of the great houses of the neighborhood. She loved the country, enjoyed long country walks, and had many Hampshire friends. It therefore came as a considerable shock when her parents suddenly announced in 1801 that the family would be moving away to Bath. Mr. Austen gave the Steventon living to his son James and retired to Bath with his wife and two daughters.

The next four years were difficult ones for Jane Austen. She disliked the confines of a busy town and missed her Steventon life. After her father’s death in 1805, his widow and daughters also suffered financial difficulties and were forced to rely on the charity of the Austen sons. It was also at this time that, while on holiday in the West country, Jane fell in love, and when the young man died, she was deeply upset. Later she accepted a proposal of marriage from Harris Bigg-Wither, a wealthy landowner and brother to some of her closest friends, but she changed her mind the next morning and was greatly upset by the whole episode.

After the death of Mr. Austen, the Austen ladies moved to Southampton to share the home of Jane’s naval brother Frank and his wife Mary. There were occasional visits to London, where Jane stayed with her favorite brother Henry, at that time a prosperous banker, and where she enjoyed visits to the theatre and art exhibitions. However, she wrote little in Bath and nothing at all in Southampton.

Then, in July 1809, on her brother Edward offering his mother and sisters a permanent home on his Chawton estate, the Austen ladies moved back to their beloved Hampshire countryside. It was a small but comfortable house, with a pretty garden, and most importantly it provided the settled home which Jane Austen needed in order to write. In the seven and a half years that she lived in this house, she revised Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice and published them (in 1811 and 1813) and then embarked on a period of intense productivity. Mansfield Park came out in 1814, followed by Emma in 1816, and she completed Persuasion (which was published together with Northanger Abbey in 1818, the year after her death). None of the books published in her lifetime had her name on them – they were described as being written “By a Lady”. In the winter of 1816 she started Sanditon, but illness prevented its completion.

Jane Austen had contracted Addisons Disease, a tubercular disease of the kidneys. No longer able to walk far, she used to drive out in a little donkey carriage, which can still be seen at the Jane Austen Museum at Chawton. By May 1817 she was so ill that she and Cassandra, to be near Jane’s physician, rented rooms in Winchester. Tragically, there was then no cure and Jane Austen died in her sister’s arms in the early hours of 18 July, 1817. She was 41 years old. She is buried in Winchester Cathedral.

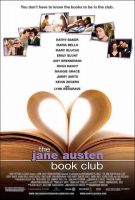

The Jane Austen Book Club (2007)

Directed by: Robin Swicord

Starring: Maria Bello, Emily Blunt, Jimmy Smits, Amy Brenneman, Hugh Dancy, Maggie Grace, Kevin Zegers, Lynn Redgrave, Kathy Baker, Marc Blucas, Catherine Schreiber, Parisa Fitz-Henley

Screenplay by: Robin Swicord

Production Design by: Rusty Smith

Cinematography by: John Toon

Film Editing by: Maryann Brandon

Costume Design by: Johnetta Boone

Set Decoration by: Meg Everist

Art Direction by: Sebastian Schroder

Music by: Aaron Zigman

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for mature thematic material, sexual content, brief strong language and drug use.

Distributed by: Sony Pictures Classics

Release Date: September 21, 2007

Views: 129