Taglines: The last thing on his mind is murder.

The Man Who Wasn’t There. 1949, Santa Rosa, California. A laconic, chain-smoking barber with fallen arches tells a story of a man trying to escape a humdrum life. It’s a tale of suspected adultery, blackmail, foul play, death, Sacramento city slickers, racial slurs, invented war heroics, shaved legs, a gamine piano player, aliens, and Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle.

Ed Crane cuts hair in his in-law’s shop; his wife drinks and may be having an affair with her boss, Big Dave, who has $10,000 to invest in a second department store. Ed gets wind of a chance to make money in dry cleaning. Blackmail and investment are his opportunity to be more than a man no one notices. Settle in the chair and listen.

The Man Who Wasn’t There is a 2001 British-American neo-noir crime film written, produced and directed by Joel and Ethan Coen. Billy Bob Thornton stars in the title role. Also featured are Tony Shalhoub, Scarlett Johansson, James Gandolfini, and Coen regulars Frances McDormand, Michael Badalucco, Richard Jenkins and Jon Polito. Joel Coen won the Best Director Award at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival. Ethan Coen, Joel Coen’s brother and co-director of the film, did not receive the Best Director Award as he was not credited as a director.

Film Review for The Man Who Wasn’t There

“Didja ever think about hair ?” asks The Barber, played by Billy Bob Thornton, snipping away at a chipmunk-favoured, comic-book-reading little boy, the crown of whose head he has turned into a hypnotic blond whorl. “How it’s a part of us? How it keeps on coming, and we just cut it off and throw it away?”

His colleague tells him to cut it out: his weird intense talk is going to scare the kid. But the Barber persists. “I’m gonna throw this hair away now and mingle it with common house dirt,” he says wonderingly, quietly, apparently on the verge of some kind of breakdown. But then, with an infinitesimally dismissive wince, the Barber waves the thought away and replaces his ever-present cigarette: “Skip it.”

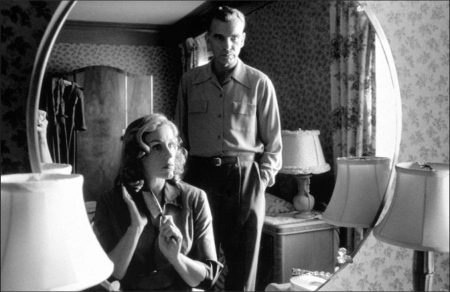

All of the power, the understatement and the profound enigma of Billy Bob Thornton’s magnificent performance is contained in that brilliantly controlled and modulated scene, difficult though it is to single that out or anything else. This movie is quite simply the Coen brothers’ masterpiece, and Thornton’s brooding presence as the Barber, Ed Crane, is a stunning achievement. He is reticent, watchful, neither ingenuous nor jaded, but toughly stoic; he’s quietly cynical and even desperate yet with a strong strain of decency, even quaintness: his strongest oath is “Heavens to Betsy!”

Ed Crane’s Americanness runs through him like a stick of rock. He has hardly any dialogue, but dominates the movie through his rumbling, tenor voiceover: he is indeed there but not there. This is a classic performance from Thornton, displaying the kind of maturity and technical mastery that we hardly dared hope for from this actor. His Ed Crane forms a kind of triangle with Henry Fonda in The Wrong Man and Gary Cooper in High Noon: a paradigm of virile, yet faintly baffled American ordinariness.

The work is a thriller in the style of James M Cain, set in suburban California in 1949 and obviously influenced by the movies of the period, yet somehow transmitting the atmospheric crackle of a strange tale from The Twilight Zone. It is the story of how self-effacing Ed Crane, in yearning for a better station in life than that of the humble barber, with his smock and scissors, succeeds only in getting mixed up in the adulterous affair being conducted by his wife Doris, played by Frances McDormand, and her boss Big Dave (James Gandolfini), leading to blackmail, bloodshed, and the shadow of the electric chair.

The Man Who Wasn’t There is shot in black-and-white by the Coens’ long-standing cinematographer Roger Deakins, with superbly observed loca tions and sets: exquisitely lit, designed and furnished. As in so many of the Coens’ films, an entire universe is summoned up, partly recognisable as our own, and yet different, a quirky variant on real life with its very own fixtures, fittings and brand names.

Doris and Big Dave work in a department store with the jocose name of Nirdlinger’s, whose creepy manikins and hulking display cabinets are shown in the empty store at night. Ed Crane reads pulp magazines with names like Stalwart, Muscle Power and Salute. Yet in one shot he’s also frowning over Life magazine, whose cover advertises an arresting article: “Evelyn Waugh: Catholics In The US”. In a previous scene we’ve seen Ed and Doris attending church on a Tuesday night for the charity bingo session: a secular High Mass for the semi-believers.

Frances McDormand is the second compelling reason to see this film, the querulous wife who married our dourly taciturn Ed after a courtship of just two weeks, and on being asked if they should get to know each other more, simply replied: “Does it get better?”

Ed is to reveal, glumly, that he and Doris “have not performed the sex act for many years”, yet somehow their relationship is saturated with a gamey erotic perfume, like the ones she gets from Nirdlinger’s with her staff discount. She lounges in the bath, asking languidly for a drag of his cigarette and getting him to shave her legs, which he does humbly, unhesitatingly: an uxorious moment of displaced sexuality which is recalled in the movie’s final, devastating scene.

With extraordinary clarity and economy, Joel and Ethan Coen present scenes from a marriage as fascinatingly fraught as anything in the cinema. All the time, Thornton’s face looms over everything, a one-man Mount Rushmore of disquiet. Later on, Ed’s pushy lawyer is to describe him as a piece of modern art, and that indeed is what he is, a piece of art, one moreover that the camera loves: his face is a composite of planes and lines, crags and wrinkles, defined by the crows’ feet that fan out as he squints into the sun, or to filter out the cigarette smoke.

What a stunning, mesmeric movie this is. I can only hope that on Oscar night the Academy are not so cauterised with dumbness and cliche that they cannot recognise its originality and playful brilliance. Noir is the catch-all term given to movies like this – yet the Coens achieve their greatest, most disturbing moments in fierce sunlight, in the outdoors and in the dazzling white light of the final sequence. So I propose a new genre for this film – noir-blanc , a seriocomic masterpiece which transforms the quotidian ordinariness of waking lives. It is the best American film of the year.

The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001)

Directed by: Joel Coen

Starring: Billy Bob Thornton, Frances McDormand, Scarlett Johansson, Michael Badalucco, James Gandolfini, Katherine Borowitz, Richard Jenkins, Tony Shalhoub

Screenplay by: Ethan Coen, Joel Coen

Cinematography by: Roger Deakins

Film Editing by: Roderick Jaynes, Tricia Cooke

Costume Design by: Mary Zophres

Set Decoration by: Chris L. Spellman

Art Direction by: Chris Gorak

Music by: Carter Burwell

MPAA Rating: R for a scene of violenc.

Distributed by: USA Films

Release Date: November 2, 2001

Views: 138