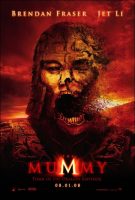

The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor. With a powerful sequence set in the Shanghai Museum, principal photography kicked off at Mel’s Cite du Cinema in Montreal. Rick and Evy O’Connell have been convinced to take the Eye of Shangri-la back to China, but with grave consequences…

The scenes were shot on a magnificent set imagined by production designer Nigel Phelps. Of course, there would be an intricate stunt pivotal to the scene, and the designer would need to coordinate around it. Explains Phelps, “We had to design a way into the space for Alex and Lin to arrive without being seen. That was a hard set to design because we had to incorporate all of that, and the chariot [driven by the Dragon Emperor Mummy] had yet to be designed. So, we were pulling and stretching and reshaping everything to accommodate.”

Production next moved outside to shoot on the stupa (gateway to Shangri-la) courtyard set, constructed next to the linking set of the Gateway, an enormous section of mountains that represented the Himalayas and sheltered a hidden gateway to the mysterious pool of eternal life in Shangri-la. The courtyard was dressed with fake snow, created by SFX supervisor Bruce Steinheimer’s team. “Rob was very specific on the snow he wanted,” explains Steinheimer. “We used 160 tons of magnesium sulfate for the ground snow.”

The fall weather in Montreal is very unpredictable, and, one night, a huge storm hit the set and washed away all the snow. In a bit of its own magic, the set dressing team was called in during the early hours to repair the damage; when the crew arrived at 7:00 a.m., there was no sign that anything damaging had happened.

Again, designs from the script would be adjusted once Phelps, DP Duggan and Cohen had regarded the model sets and discussed the best way to shoot the action. In scenes with the stupa as backdrop, the O’Connells, Jonathan and Lin confront the Emperor Mummy, and a rip-roaring gunfight, followed by help from some Yeti, ensues.

Action unit director Vic Armstrong orchestrated a complex sequence on the Gateway set, but he needed to allow for hero Yeti and mountains of snow to be strategically placed in later. In the scene, the O’Connells have been pinned down by General Yang’s army, but they are rescued by ferocious saviors. “Yang gets kicked out onto the rope bridge, and a big avalanche is formed,” recounts Armstrong, “which is actually caused deliberately by one of our heroes to wipe out his army. The avalanche rages through and collapses the bridge.”

Having successfully avoided most of the bad weather, the production moved out to the ADF stage about 40 minutes from Mel’s. There, Phelps’s team created one of the most awe-inspiring sets from the film: the mausoleum. During excavations, Alex has discovered the tomb of the Emperor. Entering the crypt, he stumbles into an incredible mausoleum filled with thousands of Terracotta Warriors. As he makes his way through the ranks, he and his companions find themselves in a series of deadly booby traps.

“When I did the research into the real Terracotta Warriors, I saw that they were all in ranks of four,” recalls Phelps. “Another surprise was that I had imagined they were little people, but, in fact, they were about six feet tall, and every one is different. The set decorator, Anne Kuljian, was remarkable with the detail for the soldiers. We made 20 different heads that you could interchange.”

It was up to the team to re-create weapons stolen hundreds of years ago by tomb looters “We bought one kind of soldier and horse in China, and then we mass produced them in a workshop in Montreal,” explains Kuljian. “I had all the weapons, armor and other items needed-like the horses’ bridles and mausoleum ornaments made in China by a team headed by propmaster Kim Wai Chung, and then shipped to Montreal.”

Returning to Mel’s, the production moved into the mysterious world of the Foundation Chamber: the setting for the brutal hand-to-hand battle between the Emperor and Rick O’Connell. This was the first scene to be shot with Jet Li.

“In the script, there is emphasis on the core of the Great Wall,” Phelps recalls.“The notion was that during the construction of the Great Wall, enemies were buried alive in the foundations. It contained a temple at the center, and the ceiling of the foundation room reflects a subterranean world that held all their bodies and souls. That forms the core of the Foundation Army that rises to attack the Terracotta Army.”

From the brutality of the fight, the production moved to the tranquility of the Shangri-la cave. This served as the backdrop for the touching reunion of Zi Yuan and the daughter from whom she’s been separated for two millennia. “Rob nailed it…how he wanted the different facets of our reaction after 2,000 years of separation,” recalls Yeoh. “It was pure joy at seeing my child again. On the flip side, for Lin, it was the outpouring of grief. All those years away of sorrow and fending for herself. ”

The cave shimmered with candlelight that illuminated the magnificent sleeping Buddha that lay along the length of it. The alcoves were filled with beautifully carved statues and a stunning pagoda that stood at the entry. The team’s goal was a simple one: make Shangri-la feel as large, open, lush and magical as possible.

Lensing in China

On October 15, production completed filming in Montreal and prepared for an even bigger adventure: shooting in China. From the beginning, it was important to the production that period authenticity be maintained. Explains Ducsay, “Even though these movies are great fantasies that take creative liberties, there is honesty to them because we actually shoot them in the locations where they are supposed to take place.”

Fortunately, the move from Montreal to China was quite smooth. Cohen recollects: “Our executive producer Chris Brigham, Chinese producers Chiu Wah Lee and Doris Tse Karwai and the China production supervisors Mitch Dauterive and Er Dong Liu actually performed a miracle. To move 200 westerners on a Friday to shoot on Tuesday seemed virtually impossible, but they did it.”

The decision to shoot this much of the movie in China was both a practical one and a creative one. Explains Brigham: “The location at Shanghai Studios, the setting for the incredible chase sequence, doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world. Once we made the decision to come here, we also needed to build sets as cover. The Tian Mo location was then added, by default, as we were already going to be here.”

Now in China, the cast and crew required to complete the epic scenes grew substantially. At one point, there were more than 2,000 people working on it. The group was comprised of 200 Americans and Quebecois, 1,700 from Mainland China and 100 from Hong Kong, as well as crew from Malaysia, Croatia, Slovenia and Taiwan.

Though many languages were spoken on set, the director didn’t worry about what could get lost in translation. “I have always felt a brotherhood among international film people,” says Cohen. “Everyone’s problems seem to be the same: money, time, vision. My C-camera operator in China, TONY CHEUNG, has been the cinematographer of many films. When he, Simon and I talk T-stops, filters and lens ratios, the words may be different, but the meaning is crystal clear.”

The Asian portion of the shoot began in the desert of Tian Mo. “We have made the move to China. Hundreds of our Chinese art department have labored for months to prepare the site for this day,” marveled Cohen on his production blog. “The dawn is breaking over the Great Wall, the original wall made of tamped earth that towers over the horizon. The sun is real; I had the wall built. The Dragon Emperor himself will mount a 50-foot-high colossus to wake his 5,000 Terracotta Warriors from 20 centuries underground and lead them in one final battle against the O’Connells and the mystical forces of his ancient enemy, Ming Guo, who has been raised by Zi Yuan. Armies will clash. Good vs. Evil. The Living vs. the Undead. In other words, it’s Monday on the set of The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor.”

The Tian Mo locale hosted multiple scenes, including the stunning sword fight between Jet Li and Michelle Yeoh and the film’s climactic, epic battle sequence between the armies of the undead. “To create the battlefield, it was necessary to design something graphically recognizable, so you would instantly know which side the Terracotta Army was coming from and which were the Foundation Warriors,” explains Phelps. “Basically, it was just a big empty space; we created the ruins to add interest.”

The Great Wall could not have been constructed without the instruction of Chinese art director MR. YI, both a historical and technical advisor to the production. This marked the sixth time the artist supervised a build of one of the Seven Wonders of the World. Other scenes shot in Tian Mo were of General Yang’s camp, constructed in a Ming Dynasty village located in a complex of caves close to Tian Mo, and the interior of the black tent in which the Emperor meets with his generals.

While at Tian Mo, the crew was housed approximately an hour’s drive away in the city of Yanqing. The area roads were heavily congested with transportation trucks, so the production and transportation teams devised a support system of staff stationed along the way-directing vehicles along the best route for the particular time of day.

Save an occasional sandstorm, the production was fortunate with the weather. Toward the end of the shoot, however, temperatures dropped rapidly and the team retreated south to Shanghai. Shooting continued at the famous Shanghai Film Studios, which lie approximately an hour’s drive outside the city.

The studio has an enormous set devoted to the streets of Shanghai in the 1940s, filled with full-size churches, bars, clubs and restaurants, as well as houses and a trolley bus. These streets provided the backdrop for the chase sequence between the O’Connells and the Emperor Mummy set during the Chinese New Year. Between the main unit and action unit work, the night shoot took three weeks to complete. While the main unit filmed in inner Mongolia, action unit director Vic Armstrong and team shot the bulk of the SFX work, plus some of the stunts, before the main unit arrived.

The chase through the streets of Shanghai offered a complicated sequence that married physical action for the actors and stunt team with CG. Bronze horses pulled a chariot with the Terracotta Emperor at the reins (as Alex and Lin hung on underneath). Hundreds of extras in period costume ducked around art deco buildings as Rick, Evy and Jonathan maneuvered a truck loaded with fireworks to stop the Emperor.

Cohen recalls filming a section of the chase with no less than eight cameras: “Vic Armstrong blew up a trolley on the main street in the Shanghai Bund section. Rick and Jonathan took the mother of all rockets and aimed it right at the fleeing chariot. Jonathan lit the fuse with his Dunhill lighter; the rocket ripped down the boulevard, and the mummy deflected the rocket straight into the trolley. The trolley blew 10 feet straight up into the air, with a fireworks display that could be seen from outer space.

“R. Bruce Steinheimer had designed the event with an extensive team of American and Chinese fireworks experts,” Cohen continues. “The concussion was so intense that it broke every window in the street and the rocket’s red glare set the third story of the set on fire. It was glorious!”

Shanghai Studios also housed several other sets, including the Emperor’s Throne Room, a testament to craftsmanship. A team of Chinese cultural advisors aided Cohen in understanding the complex Qin Dynasty language, ceremonies and behaviors. He relates, “This film has been packed with new knowledge: art and intellect people would stand at the Emperor’s left, military at his right; musicians were not allowed swords; no one was allowed to turn their back to the Emperor. The film gods dwell in the details; even if it’s a world that you are not familiar with, it feels true.”

The final scenes of the shoot took place in Jonathan’s fantastic 1940s Egyptian-style nightclub (in a nod to the first two films, it was named Imhotep’s) on the Bund run. It was created to be a believable hot spot one might expect of Shanghai in the era-glamorous and larger than life.

While the main unit finished its work at Shanghai Studios, the action unit took a four-hour drive south of Shanghai to shoot a dramatic battle sequence at Hengdian World Studios. One of the largest studios in Asia, Hengdian offers complex environments that showcase different periods from Chinese dynasties. These include life-size replicas of Emperor Qin’s palace, Qing Ming Shang He Tu, the palaces of the Ming and Qing dynasties and the Grand Hall of Dazhi Temple-complete with a figure of Sakyamuni 28.8 meters high, the tallest indoor figure of Buddha in China.

The filmmakers were duly impressed by propmasters such as Chueng Kim Wai, who managed a crew that replicated the mystical world in which the Emperor lived. For example, it wasn’t unusual to find a master craftsman carving an intricately-detailed altar for the temple square on a massive block of polystyrene-with only a small, out-of-focus, black-and-white photo of the altar as reference material.

The production designer was stunned to find that many of the Hendigan props were actually real. Remembers Phelps: “The weapons for the 500 figures in the Terracotta Army were all made of bronze, and all the crossbows had working mechanisms. A lot of things get lost in translation, but no one expected bronze weapons, because it would be crazy in a budgetary sense. However, the way they do it here…it is actually cheaper to do it for real than to make it out of fiberglass. It adds another level of believability when the actors touch the swords and they are cold.”

Creating an Epic Backdrop: Production Design

When Phelps first met with the director, he knew they would be embarking on an immensely challenging creative journey. It was vital to Cohen that The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor have an epic look and feel to it, and that meant Phelps would need to give the production a unique and mythic visual canvas. A lifelong dream of the director’s-to share the fantastic culture and heritage of China in a film with the scope of this picture-the shoot was a challenge like nothing the two men had ever faced. And it all started with the design.

“When you begin a project like this and everything has to look huge, you have to decide how much will be physically built and how much will be digital,” explains Phelps. “That’s the equation you work out with the director. Going to China completely opened up the world to do a lot more physical scenery than we could have done anywhere else. When you conceive sets like a mausoleum that contains the Terracotta Army, it’s obviously not going to be an intimate little set.”

The style of the film naturally evolved from Cohen’s lifelong passion for Chinese culture and his Buddhist studies. He was concerned to make everything as true as possible, and the partners in design depicted a good deal of spiritual scenery in the film-particularly in the Himalayas and the stupa courtyard. For Cohen, the film’s design informed a world that reflected “Chinese history in an unusual way, and had a lot of fun with it as we explore two periods: the true history of 200 B.C. and the state of affairs in China in 1946.”

While collaborating with Phelps for the film’s look, Cohen voraciously read of the stories of the Terracotta Warriors of Xi’an, the Warring States period before the unification of China, the First Emperor’s immortality quest and the Great Wall’s construction.

The director and production designer agreed they did not want to be restricted in camera moves when it came time to lens the world’s most powerful emperor roaring across the continent (within two periods of two millennia), so the majority of the sets had to offer cinematographer Simon Duggan and his crew “360-degree shoots.” To create these enormous set pieces in Canada and China, Phelps began study that continued throughout the production. A team of Montreal researchers assisted him as they all worked at a rapid pace to design; it continued as they moved from set to set, followed by hundreds of construction crew workers to manifest their sketches.

Form would not always follow the original screenplay’s function; Phelps and Cohen remained open to expanding upon the script as they scouted locations. The designer gives an example that altered the film’s original beginning: “When we first came to China to scout, we traveled to Ningxia to look at these sand dunes the size of Denmark. I was flipping through a hotel brochure, a sort of `What’s on in Ningxia,’ and I discovered these pyramids that were absolutely phenomenal.

“The landscape is very similar, geographically, to what we had in Tian Mo [a desert area north of Beijing]-the foothills, the mountains and everything surrounding it,” he continues. “The shot was unscripted, but I knew Rob would love it so I brought him the idea and we decided to use it at the beginning of the film. People will look at the pyramids and think they are CG…you just don’t expect to see these things in China.”

The massive pyramids reside in a valley of hundreds of tombs that contained the remains of a race of Chinese annihilated by the Mongolians-because members of their tribe shot the arrow that killed Genghis Khan. It has only been a couple of hundred years since the Chinese began uncovering this land that had been completely forgotten. These tombs are the last vestiges of the culture of a people who killed the terrifying ruler.

The designer, veteran of such epic films as the blockbuster Troy, explains his unique take on imagining a film: “When I read a script, I look at the story and I see everything in terms of light and shape. This is light, and that is dark; this is tall, thin and that is short, fat. You want a variety and balance that goes with the way everything works with the script narrative. It’s a bit like music; the same principle applies to color.”

As his team worked on illustrations for The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor, Phelps was inspired to have gold light serve as the primary influence on the film’s color palette. For example, one of the first sets his team created was the stupa courtyard set, in which they used thangkas (colorful painted scrolls) with frescoes on the perimeter. As the set was in shadow and Phelps and DP Duggan needed a swatch of color to catch the audience’s eyes, a member of the team suggested they use gold leaf on certain sections of the paintings.

“Gold is a great color that goes with everything,” concludes Phelps. “You can take it up or take it down; it works really well with the earth tones and the reds. It became a link in all of the sets-even in Imhotep’s nightclub set, where the color temperature of the lights gave that amber color through everything.”

Battling the Undead: Swordplay and Martial Arts

It wouldn’t be a Mummy movie without intricate fight sequences. Any sequence involving master martial artist Jet Li raises the bar, but add to the film Brendan Fraser’s Krav Maga, Michelle Yeoh’s swordplay, Isabella Leong’s kung fu, Luke Ford’s martial arts-inspired street fighting and Maria Bello’s combination punches and you have a feast for fight fans.

Jet Li commends what was impressive about his director’s grasp of staging an exciting fight: “Rob has a very good understanding of the timing and the fast pace that is so important in a fight sequence, and he uses very interesting angles.”

Key fights in the production include one set in the Foundation Chamber, the subterranean temple in which the Emperor attempts to raise his Terracotta Army. With ceilings formed from the bones of conquered enemies, the chamber is filled with flickering flames that line the walkway as the Emperor weaves his dark magic.

In the sequence, Rick O’Connell confronts the Emperor by throwing a knife into his back. The Emperor, only slightly inconvenienced, yanks it out and attacks O’Connell with a rage pent up over centuries of being cursed. O’Connell races at him, and an incredible hand-to-hand battle ensues.

Cohen came up with the idea that, in the years since we last met our hero, O’Connell had become skilled in the type of practical street fighting found in the short, sharp moves of Krav Maga. “It’s a system of combat defense devised by the Czech Jews during the Second World War,” explains Fraser. “They started fighting back by using a system of body motions based on instinct. Basically, you go to the problem, rather than let it come to you. It’s confidence building and, needless to say, great exercise.”

“Brendan is a fantastic action actor,” commends Vic Armstrong. “He’s really been working out, and he is rock solid. He loves his action and knows what he is good at, so we catered to that in all fights we’ve done with him.

Asian fight coordinator Mike Lambert, who worked with Michelle Yeoh in her breakout role in Tomorrow Never Dies, was primarily responsible for training the actors and choreographing the fight sequences in conjunction with stunt coordinator Mark Southworth. Lambert, who has lived in Hong Kong for years, knew many of the film’s actors from having taught them in that country.

One sequence that fascinated the Chinese press was the sword fight between Jet Li and his longtime friend Michelle Yeoh. The fight takes place in the desolate beauty of Tian Mo desert and represents the first time Li and Yeoh have been on opposing sides of a film fight. “It’s funny,” says Yeoh. “If you looked at our shooting schedule, it said, `The fight that the whole of Asia is waiting for.’”

Of the duo’s fighting sequences and trainers, Yeoh offers, “Jet’s fight coordinator, De De Ku [affectionately known as Master De], is a longtime collaborator. He is so brilliant…we just stand there and let him weave his artistry around us. Jet and I understand each other. We are on the same beat and just doing the best we can.”

Jet Li agrees: “When you find a good player to fight with you, it’s like having a good opponent at tennis. You have to be on the same level to play well. I very much enjoyed working with Michelle, and I hope to do so in the future.”

Other actors also had their fair share of the action. Maria Bello lived a childhood dream in a fantasy sword fight sequence-an homage to swashbucklers-as Evy. “Maria’s character is a lot more refined,” explains Lambert. “She is a little more expert in martial arts, but she has also picked up Rick’s street-fighting style. Alex is a bit of a stylist, but again with a little bit of his father’s raw, street-fighting style mixed in.”

Luke Ford prepared for almost three months before production began. Necessary, as he would have to dodge a barrage of booby traps to awaken the planet’s newest threat. “I spent five days a week working on the fight training,” explains the actor. “I began with cardio, weights and stretching. Then I progressed into training for the fights; there were some martial arts, but also a lot of swashbuckling, punching and kicking. It was pretty intense.”

Ford’s sparring partner, Leong, also spent much time training in martial arts. Adds Lambert, “Every spare opportunity Isabella had, she came to train and stretch. She put in a lot of hours and it really inspired her to do more.”

Known for pushing the envelope in his action sequences, Armstrong went all out for this production. “It is just nonstop,” says the master stunt choreographer. “It’s the kind of film I can really get my teeth into-with all sorts of action, from large scale down to interesting chases, fights and Jet Li’s martial arts.”

During the key Shanghai chase sequence in which the Emperor Mummy drives through Shanghai on his chariot of four horses (filmed at Shanghai Studios), the sarcophagus flies through the streets while Lin and Alex desperately hang on. All the time, it is closely followed by the rest of the O’Connells on a truck loaded with fireworks. “It’s a bit like Stagecoach crossed with Ben-Hur,” laughs Armstrong. “We’ve got the two young leads in the movie fighting with Yang, who’s on the front of the chariot with the Emperor. It was a huge sequence and very complicated. We had a 500-person crowd every night for about two weeks.”

There was also a fair amount of horse riding needed for the film; this took place in Tian Mo. Much of the horse work was done by the actors themselves, and the necessary stunt work was accomplished by Chinese stunt riders. Michelle Yeoh rides with Russell Wong, who has action sequences with his group of 12 warriors, and Jet Li rides his horse into battle.

Once Armstrong and crew had completed work on key chases, they moved down to Hengdian World Studio to complete the final action sequences. Armstrong reflects, “With every sequel, you have to raise the bar, and the ones that have gone before have been very good, so it was quite a challenge. It’s really interesting watching Rob work, with the speed of the shots he wants as much as the length of the shots.”

Cohen also enjoyed their collaboration, especially Armstrong’s ability to execute ambitious projects with a keen eye for safety. “Vic has done everything from the Bond films and Indiana Jones to everything in between,” nods the director. “He is one of those guys who takes your idea, builds on it and knows how to create it so it can be done safely.”

VFX and SFX: Blending Fantasy and Reality

To create the most complex sequences in The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor, a seamless blend of visual and mechanical artistry would be required. With an amazing range of effects-from ancient creatures and avalanches to intricate battle sequences with massive numbers of digital characters in digital environments and practical effects-the filmmakers had an enormous task at hand.

Accomplished VFX producer Ginger Theisen headed the visual effects department. For the large number of VFX shots required, more than 800 at last count, Theisen brought on two digital houses: Digital Domain, headed by VFX supervisors Matt Butler and Joel Hynek, and Rhythm & Hues, headed by VFX producer Derek Spears.

The SFX department was led by industry veteran SFX supervisor R. Bruce Steinheimer. In order to develop the large number of mechanical effects for the film, he oversaw four different SFX shops in Montreal and China. Says Steinheimer, “We had over 100 people working in effects on different continents at the same time in order to make sure all the effects would be ready for both the main and the action units.”

Steinheimer was tasked with creating mechanical effects that would blend into digital extensions of CG creatures. In the Shanghai chase sequence, for example, the chariot needed to interact with its surroundings as if it was being pulled by real horses. He explains, “We put a plow on the front of it so we could crash into things, because the Terracotta Emperor and the bronze horses are in the digital realm. As the part of the chariot, they are on separates and start to spin out of control, so we used a hydraulic spin rig that travels down a track to create that effect. It ejects the sarcophagus, which slides through the streets, causing mayhem and destruction.”

After the shots of the chariot crashing through buildings were completed, a plastic horse was attached to the front of the chariot to give reference for the performers when they filmed. “This gave our actors something to ride on,” explains VFX producer Spears. “We replaced the plastic horse with our CG bronze horse later.”

“All the horses were, originally, very heavy bronze statues built by the ancient Chinese,” explains animation director Craig Talmy. “When they buried their dead emperor, they adorned his burial place with regal statues of horses.” After Alex O’Connell accidentally lifts the curse, the horses “come alive.” “We had to make them look like real horses,” continues Talmy, “with their weight, structure and underlying bones and musculature. At the same time, they’re made of bronze, so they have to move in a way that suggests hollow metal about an inch thick.”

Raising the Emperor Mummy

For the Emperor Mummy and his legion of Terracotta Warriors, the effects team developed a series of “liquid solid” warriors made of clay, who were able to flex and bend at will. Whenever they move, they crack and reform.

In order to begin work on the character of the Emperor Mummy, a cyberscan was performed on Jet Li using multiple three-dimensional cameras; a submillimeter three-dimensional model of his entire body was created. Digital Domain motion captioned his entire body, then “staccatoed it” to infuse the characteristics of a terracotta statue.

Cohen expands upon the process: “Instead of using makeup, we created a three-dimensional image of Jet Li’s face by taking very complex measurements of his face while he acted the part. Then, we made a CG image of him that can talk, which is the essence of the real actor. We wrote in new algorithms to describe geometries which fracture and reform. So, every time he speaks, it fractures; it is constantly breaking and reforming.”

As the Emperor has control over all of the elements (earth, fire, air, water and wood), he is quite a dangerous foe. To add insult to injury, he possesses off-the-chart healing powers. Explains Joel Hynek, co-VFX supervisor at Digital Domain: “He is filled with magma, so when he cracks, pieces fall off; the magma comes to the surface and rapidly solidifies-and he becomes the replenished terracotta-statue emperor.”

The trick for the VFX team was to give the Emperor movement without making him look as if he was a human wearing a rubber mask. Digital Domain had some science experiments of its own as they performed stress studies on terracotta. They wanted to know what it looked like when it was expanded, cracked and crushed, and incorporated the results into the look of the mummy and his legion of doom. Hynek elaborates, “The Terracotta Warriors don’t heal unless they can get across the wall; they will continually deteriorate. However, if they can cross the wall, they become immortal.”

Crafting Legions of Warriors

Though only a fraction of the Terracotta Warriors have been excavated from the depths of Chinese soil, the production was tasked with bringing them all back to life. Digital Domain was responsible for the creation of the vast armies of both the Terracotta Warriors (the Emperor’s men) and the Foundation Army (those killed by the Emperor). They had to render a total of 2,500 Foundation Soldiers and 4,800 Terracotta Warriors.

“The Foundation Army are the good guys,” explains co-VFX supervisor Butler. “These are the workers that have been incarcerated under the Great Wall of China for a couple of thousand years. They come to life as desiccated beings that have a really spooky look. We didn’t just build them as skeletons, but in a multitude of degraded states-from `healthy guys’ to complete `bone men.’ It was tough, actually, because it was hard to depict a desiccated being as having a good character.”

By examining reference materials from ancient embalming imagery to often-macabre books on anatomy and physiology, the team became quick studies on kinesiology and musculature. “Using the research material,” explains Butler, “we built a set of tools that enabled us to take a body from an undamaged-but-aged form down to muscles, tendons and sinew-in their decayed form-down to bare bones.”

In order to give each character independent movement, Digital Domain used a program called Massive, developed by Stephen Regelous and used for battle scenes for multiple films-including those of The Lord of the Rings trilogy. “Stephen designed and created a tool set that allows you to render thousands of sentient beings, whether they are humans or creatures,” explains Butler. “They all have their own individual decision-making capabilities. He refers to these individual characters as `agents.’ Each agent has the capability of making his own decision, based on rule sets designed by the artist. So the artist is literally designing the brain.”

The original Terracotta Warriors provided their own reference, as each of the Xi’an Warriors was crafted with a unique face, hairstyle and body type. After scanning images of them, the team devised cunning ways to swap and exchange body parts, so the audience never sees two of the same soldier as they roar across a battlefield. When a geometric library of warriors were married with an assortment of terracotta textures, lighting, shade and movement helped to render thousands of unique soldiers.

Now, the team just needed to provide motion to the warriors, while they broke apart again and again. Not an easy task, because they had to take inanimate objects and build motion and fighting movements into their repertoire of behaviors. “Before we did anything, we did a Battle Action Reference Shoot,” explains Hynek. “Vic Armstrong, Matt Butler and I started working with different battle actions, then Matt and Vic worked in Montreal to capture what we needed.”

“It was important to Rob that the warriors look real and not just like replicated figures,” explains Armstrong. “They are very grandiose, epic-style battles and, luckily, 21st-century technology is a big help. I worked closely with the VFX guys to plot every shot. I did a lot of motion-capture work with a mixture of live people to represent the two armies-blue suits for the Terracotta Warriors and green suits for the Foundation Army. They are actually fighting, so it looks realistic. The computer took the physical movement of a real person and replaced it with the CG terracotta and skeletal figures. The staging of the fight is also important. It has to have enough humor to release the tension, but, at the same time, it has to look violent and realistic.”

Building New Creatures

In addition to his incarnation of the Terracotta Emperor, Jet Li’s character also has the ability to morph into other forms, specifically a three-headed gorgon that is derived from a mixture of Western and Chinese mythology. Image Matrix projected Li’s performance onto the CG creature that spits fire, snatches a victim and flies away.

“The Emperor chose his first incarnation to be a 30-foot, three-headed gorgon,” explains Rhythm & Hues’ digital supervisor Bob Mercier, “so we had to decide how much the face should look like Jet Li and how much it should look like the head of a reptile. It needed to have the spirit of Jet, yet the Mummy character should somehow come through as snakelike, but with a soul underneath. It was our goal to give an Asian influence to the gorgon’s face. You can see a ghost of Jet Li there, but it still works as a creature.”

Another incarnation of the Emperor is the Nian, a half-lion/half-dog creature based on the Foo Dog, a temple guardian of ancient China. Shares Cohen, “We’ve taken it into a much more extreme bestial concept; it is a very large creature about nine-feet high who can grab a plane right out of the skies. Jet’s character is a shape-shifter, and this is one of the different creatures he can become.”

For each creature, Rhythm & Hues produced a 3-D computer-generated model, which shows muscle tone and skin texture. This was sent to the filmmakers for their input. “Once the model was agreed on by everyone, we moved forward and began the animation,” explains animation director Talmy. “We send it down the pipeline to the rigging department-the people who populate the models with all the mechanics to allow them to not just move, but move in the way we want them to.”

As no one has seen a Yeti up close and lived to tell the story, the characters were computer generated and the VFX team was given free reign in the designing the brutes. “The Yeti have always been a favorite part of the movie for the filmmakers,” states producer Daniel. We’ve always thought it was just really cool to have the Yeti and Shangri-la be a part of this movie. The Yeti are other creatures, like the Mummy, that people from all cultures can relate to.”

Cohen wanted his abominable snowmen to have unique personalities. With no dialogue for the Yeti (save roars and grunts), the animation team needed to convey everything through body language. Laughs Talmy, “We had to find a way to pump character performances into a scene where all that’s required of our character is that he run down a hill and smash a guy in the face.”

The Yeti were originally designed to be a cross between a man, polar bear and snow leopard. Over time, the animators moved the design closer to that of a man. They liked the fact that the creature-when obeying the enigmatic Lin-could pick up an enemy, give him a razor-sharp look of disdain, then toss him into the frozen wilderness.

Action Costuming

The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor is the third collaboration between costume designer Sanja Milkovic Hays and Cohen. One of the biggest challenges was creating costumes for the beginning of the film. “There was very little to go on,” explains Hays. “There was some reference to jewelry, a few drawings, a bit of cloth and discovered mummies. I based most ideas on research from museums and books. The most useful were findings from Xi’an; we went there to look at the Warriors.”

Hays and two sketch artists worked nonstop for four months to imagine the costumes for Cohen’s world. “After you have a sketch approved, the second part of the creative process starts,” she explains. “You look for fabrics and the details from all over the world-from Hong Kong, China, Thailand and India to New York and Europe. I used hundreds of yards of fabric, many which I bought in Montreal.” Particularly, silks-which take dyes beautifully-were used to complement the film’s Asian themes.

The designer supervised a large team on two continents. She created a huge workshop at Mel’s Cite du Cinema, where she employed craftsmen from every area of expertise: a sketch artist, cutter fitters, embroiderers and jewelry makers. She also outsourced to Film Illusions, a company that specializes in unique costumes for the film industry and was responsible for creating the Emperor’s armor.

Hays designed a new look for Rick, therefore more mellow outfits were created for Fraser, more “John Wayne.” She says, “Brendan now wears a few suits and looks terrific in the ’40s look; he is so built now. As the action begins, we put him in a bomber jacket to toughen him up, and, toward the end of the movie, he goes back to his `mummy chaser’ look: pants, shirts and big guns…so he becomes the Rick O’Connell everyone knows.”

Designing for Luke Ford was amusing. “Luke starts the movie down and dirty; a Marlboro man with a 1946 leather jacket, unshaven,” she explains. “He carries that look beautifully, as he is tall and has such great charisma. Then, we clean him up and switch him into the white tuxedo, Bogart-style. Alex is more like a ’40s hip-hop, with the big, baggy pilot pants, big old shoes, big jacket. It all is very proper period, but the silhouette is more modern and appealing.”

Isabella Leong’s character begins as an anonymous assassin. Cohen and Hays agreed on a tunic look that kept the moving shadow hidden…and tricked the unsuspecting into believing Lin is a man. “For the scene in the museum where she tries to save Rick and Evy,” Hays explains, “I dressed her up for Chinese New Year in a coat-a little Matrix-style. She needed to be ready for action, so we added dress pants underneath. The coat is a long cut, so when she flies through the air, it flies behind her.” For Li’s long trek back to Shangri-la, the costumer provided her with a warm outfit inspired by the Tibetan national costumes.

The designer created nine stunning costumes for Michelle Yeoh, designs not exactly determined by the period. Hays notes, “She is a sorceress, so it gave me more freedom. When Michelle put them on, they became alive. She is so graceful and wears the costume so beautifully. The way she moves and holds her neck…she almost floats.”

One of Yeoh’s costumes was inspired by Chinese ethnic minority clothes. Recounts Hays, “It was for the big sword fight with Jet Li where she wears a pleated skirt. I bought a knee-length skirt for myself in Shanghai; I swirled in it, and the way it moved was amazing. We made it in a long version, and one of the girls here, Malika, went through hell trying to figure out how they did it. Everything was hand-pleated, but we finally figured it out. The skirt is very straight when Michelle is standing, but when she kicks, fights and swirls in it, it flies out in a full circle. I can’t wait to see it on screen.”

Designing armor for Jet Li was a long process, one Hays started months before photography began. It was the first thing she designed, as many needed to know what the armor was going to be-in particular the visual effects and art departments.

Hays had to design several versions of the armor, as each served a different purpose. “For the scenes where he walks around and looks majestic, we created the heavier outfits, which used the replica jade pieces. We had to come up with a much lighter version for the fight sequences, so he is able to move properly. Finally, we needed a version for VFX as he turns into terracotta, covered in mud and goo.

“Initially, I got into these philosophical discussions about the Emperor and his search for immortality with Rob,” Hays concludes. “We realized that the jade in ancient China was connected with immortality, and that he may have been dressed in jade just before he died. Rob and I got very excited because armor had never been made out of jade. Then the search started for the perfect piece of jade to give it the color, and how to make it. Each piece was individually done and they are connected.”

After 91 days of shooting and more than 2,000 shots filmed on two continents, The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor wrapped. For Rick O’Connell himself, it was hard to say good-bye again, but he was excited that another chapter was beginning. Brendan Fraser closes: “The spirit of this film is one of adventure, fun, romance, things that go bang, lots of action, some great fights. We’re here to entertain.”

To celebrate the wrap of principal photography in truly Chinese style, SFX supervisor Steinheimer created a fireworks display that lasted nearly eight minutes. Crewmembers, who inevitably had become blasé to the excitement of explosions, stunts and other daily events, stood wide-eyed at the incredible showstopper-a fitting end to the roller-coaster action-adventure of The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor.

The parting words go to our director. Concludes Cohen of time spent immersed in a culture he cherishes: “China was a great place to set a movie that has fantasy, imagery, history and incredible action. I would like people to feel that the culture of China has been dealt with very fairly and beautifully. The Chinese are very warm and emotional people. If you have the proper respect for their culture, they will meet you not just halfway, but 80 percent of the way. They are wonderful, artistic collaborators.”

The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor (2008)

Directed by: Rob Cohen

Starring: Brendan Fraser, Maria Bello, Jet Li, John Hannah, Michelle Yeoh, Isabella Leong, Anthony Chau-Sang Wong, Russell Wong, Liam Cunningham, Albert Kwan, Jessey Meng, Tian Liang

Screenplay by: Alfred Gough

Production Design by: Nigel Phelps

Cinematography by: Simon Duggan

Film Editing by: Kelly Matsumoto, Joel Negron

Costume Design by: Sanja Milkovic Hays

Set Decoration by: Anne Kuljian, Philippe Lord

Art Direction by: John Dexter, David Gaucher, Isabelle Guay, Nicolas Lepage, Jean-Pierre Paquet, Scott Zuber

Special Effects: Koordinatörü R. Bruce Steinheimer

Music by: Randy Edelman

MPAA Rating: PG-13 for adventure action and violence.

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Release Date: August 1, 2008

Views: 165