The Passion of the Christ Movie Trailer. “The Passion” (taken from the Latin for suffering, but also meaning a profound and transcendent love) refers to the agonizing and ultimately redemptive events in the final 12 hours of Jesus Christ’s life, of which there are four separate accounts in the New Testament of the Bible, and the legacy of which has been reflected upon for the last 2000 years. The powerful imagery surrounding The Passion has long inspired the artistic imagination, becoming a deep and abiding influence in Western painting as well as inspiring numerous motion pictures in the last century.

As early as the silent movies of Thomas Edison, The Passion was a theme addressed by the most ambitious of filmmakers. In 1927, Cecil B. DeMille directed the first epic treatment of Jesus’ life and death with the silent film The King of Kings. Then, in 1953, 20th Century Fox kicked off the new CinemaScope technology with The Robe, starring Richard Burton as a Roman tribune who seeks redemption after the crucifixion. By the 1960s, Biblical epics had become a whole film genre unto themselves, with George Stevens creating the monumental The Greatest Story Ever Told featuring lavish sets and an all-star “cast of thousands.”

Around the same time, the Italian film master Pier Paolo Pasolini approached the subject in an entirely fresh way with The Gospel According to St. Matthew, which featured a completely non-professional cast, a naturalistic style and language taken directly from the Bible, and became the most successful film of Pasolini’s career. In the 1970s, The Passion was represented in two counter-culture musicals: Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar. More recently, director Martin Scorsese was also drawn to examine Christ’s final days with his own controversial The Last Temptation of Christ.

But never before has any filmmaker attempted to bring this story of passionate sacrifice to life with such intensely focused cinematic detail and realism. For Mel Gibson, creating such a film was a long-lived dream, taking a significant amount of his own passion and that of many others, including his Icon producing partners Bruce Davey and Steve McEveety, to turn into reality.

“My intention for this film was to create a lasting work of art and to stimulate serious thought and reflection among diverse audiences of all backgrounds,” says Gibson. He continues: “My ultimate hope is that this story’s message of tremendous courage and sacrifice might inspire tolerance, love and forgiveness. We’re definitely in need of those things in today’s world.”

Gibson first began to research the scriptures and events surrounding The Passion more than 12 years ago, when he found himself in the midst of a spiritual crisis which led him to re-examine his own faith, and in particular, to meditate upon the nature of suffering, pain, forgiveness and redemption. Gibson, who as a director last brought to life 13th Century Scotland in the Oscar-winning Braveheart, realized he now had a unique opportunity to put his art where his heart resided. He imagined bringing the full power of modern motion picture technology – and especially current cinema’s realistic and visceral cinematography, production design and performance styles – to the subject of The Passion.

Gibson co-wrote a screenplay with Benedict Fitzgerald Wise Blood that drew faithfully from the Gospel accounts of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John as the script’s main sources. Still, Gibson knew he was going into largely unexplored artistic territory ‘ into the realm where art, storytelling and personal devotion meet. “When you tackle a story that is so widely known and has so many different pre-conceptions, the only thing you can do is remain as true as possible to the story and your own way of expressing it creatively,” Gibson says. “This is what I tried to do.”

As for his decision to highlight physical realism, Gibson says: “I really wanted to express the hugeness of the sacrifice, as well as the horror of it. But I also wanted a film that has moments of real lyricism and beauty and an abiding sense of love, because it is ultimately a story of faith, hope and love. That, in my view, is the greatest story we can ever tell.”

The Passion of The Christ is directed by Mel Gibson and produced by Bruce Davey, Gibson and Steve McEveety. Enzo Sisti is the executive producer. Among the talented crew joining the production are four-time Oscar nominee Caleb Deschanel as director of photography, award-winning Italian production designer Francesco Frigeri, double Oscar nominee Maurizio Millenotti as costume designer, the special effects makeup team of Keith VanderLaan and Greg Cannom (who has twice won an Academy Award) and two-time Oscar nominee John Wright as editor.

Aramaic: An Ancient Language Comes Alive

One of Mel Gibson’s earliest decisions as director of The Passion of The Christ was to have the Jesus of his film speak the same language that the historical Jesus spoke 2,000 years ago. That language is Aramaic, an ancient Semitic tongue closely related to Hebrew that today is considered by some linguists to be a “dead language,” still used in dialects by only a small number of people in remote parts of the Middle East.

“Once, however, Aramaic was the lingua franca of its time, the language of education and trade spoken the world over, rather like English is today. By the 8th Century, B.C. the Aramaic tongue was widely in use from Egypt to Asia Major to Pakistan and was the main language of the great empires of Assyria, Babylon, and later the Chaldean Empire and the Imperial government of Mesopotamia. The language also spread to Palestine, supplanting Hebrew as the main tongue some time between 721 and 500 B.C. Much of Jewish law was formed, debated and transmitted in Aramaic, and it was the language that formed the basis of the Talmud.

Jesus would have spoken and written what is now known as Western Aramaic, which was the dialect of the Jews during his lifetime. After his death, early Christians wrote portions of scripture in Aramaic, spreading the stories of Jesus’ life and messages in that language across many lands.

As the historical language of expressing religious ideas, Aramaic is a common thread that ties together both Judaism and Christianity. Professor Franz Rosenthal wrote in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies: “In my view, the history of Aramaic represents the purest triumph of the human spirit as embodied in language (which is the mind’s most direct form of physical expression)… [It was] powerfully active in the promulgation of spiritual matters.” For Gibson, too, there was something ineffably powerful about hearing Christ’s words spoken in their original language. But to bring Aramaic to life on the modern motion picture screen was going to be an enormous challenge. After all, how do you create a film in a lost First Century tongue in the middle of the 21st Century’

Gibson sought the help of Father William Fulco, Chair of Mediterranean Studies at Loyal Marymount University and one the world’s foremost experts on the Aramaic language and classical Semitic cultures. Fulco translated the script for The Passion of The Christ entirely into First Century Aramaic for the Jewish characters and “street Latin” for the Roman characters, drawing on his extensive linguistic and cultural knowledge. After translating the script, Fulco served as an on-set dialogue coach and remained “on call” to the production, providing last-minute translations and consultations. To further authenticate the language, Gibson also consulted native speakers of Aramaic dialects to get a sense of how the language sounds to the ear. The beauty of hearing this dying language spoken aloud, he recalls.

Ultimately, the entire international cast of The Passion of The Christ had to learn portions of Aramaic ‘ most doing so phonetically ‘ becoming perhaps one of the largest groups of artists ever to take on an ancient tongue en masse. For Gibson, the film’s “foreign language” had another benefit: learning Aramaic became a uniting factor among a cast made up of many languages, cultures and backgrounds. “To bring a cast from all over the world to one place and have them all learn this one language gave them a sense of common ground, of what they share and of connections that transcend language”, he says.

It also compelled the cast to look more deeply into their physical and emotional resources above and beyond the use of words. “Speaking in Aramaic required something different from the actors”, observes Gibson, “because they had to compensate for the usual clarity of their own native language. It brought out a different level of performance. In a sense, it became good old-fashioned filmmaking because we were so committed to telling the story with pure imagery and expressiveness as much as anything else”.

Labors of Larger Love: The Cast Takes on Their Roles

From the beginning, Mel Gibson knew a key to making The Passion of The Christ would be finding an actor capable of embodying to the highest degree possible both the humanity and spiritual transcendence of Jesus Christ. Gibson sought an actor who could lose himself in the role entirely, and whose identity would not interfere with the realism the director was seeking.

The search led Gibson to James Caviezel, last seen in The Count of Monte Cristo. Gibson had been riveted by a picture he had seen of Caviezel ‘ especially by the actor’s penetrating eyes and transparent expressions, which Gibson felt had the rare ability to convey the essence of love and compassion in utter silence.

When Gibson called Caviezel early on, the actor was so taken aback his response was “Mel Who'” Gibson jovially responded “Mel Brooks”. But the conversation soon turned serious when Gibson explained the role that he had in mind for Caviezel – a role Gibson told the actor he considered so tough and fraught with potential pitfalls he himself would balk at playing it.

Caviezel was daunted but energized by the challenge before him. It struck him as a remarkable coincidence that he had just turned 33, the same age as Jesus in the last year of his life. A practicing Catholic, Caviezel also found inspiration in his own religious beliefs and devotion, using prayer as a means to more deeply explore the character, words and tribulations of Jesus.

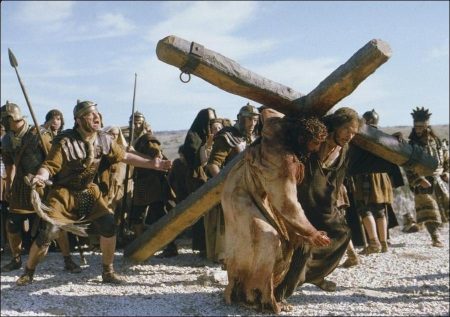

But really nothing could have prepared him for the incredible journey he would undergo during the production of The Passion of The Christ. As Caviezel explains: “For day after day of filming, I was spat upon, beaten up, flagellated and forced to carry a heavy cross on my back in the freezing cold. It was a brutal experience, almost beyond description. But I considered it all worth it to play this role”.

Gibson was quite clear to Caviezel from the start that it was his intention to film Jesus’ suffering with as much authenticity as possible, never flinching from the chaos and violence that Christ was swept up in according to accounts. Even for Caviezel, the torment Jesus endures throughout the film was terrifying at times but he says: “No one has ever showed Jesus in this way before, and I think Mel is showing the truth. Mel hasn’t used violence for violence’s sake and it has never felt gratuitous. I do think the realism will probably shock some people but that is why the film is so incredibly powerful”.

During the demanding production, Caviezel had to face his own physical vulnerabilities in a profound way. In one of the film’s most graphic sequences, Christ is scourged ‘ or whipped ‘ extensively, then further flayed with an infamous Roman torture device known as a flagrum, or “the cat o’ nine tails,” a whip designed with multiple straps and embedded with barbed metal tips to catch and shred the skin and cause considerable blood loss. To capture Christ’s resulting wounds, Caviezel had to undergo grueling, full-body makeup sessions that lasted for hours. But that was just the beginning of his trials, for the irritating makeup soon caused his skin to blister, preventing him from even sleeping during this time.

He also spent more than two weeks filming the crucifixion scenes, during which he had to carry, or more often drag under great duress, a 150-pound cross (about the half the weight of a real crucifixion cross) to Golgotha, and later to be suspended from it. Caviezel trained for the tortuous positions he would have to stand in by holding squats against a wall for up to ten minutes at a time and lifting weights to strengthen his lower back. In addition, he spent these weeks working in a loin cloth in the middle of the Italian winter, and experienced several bouts with hypothermia, often becoming so cold he could no longer speak. At times, the crew had to put heat packs on Caviezel’s frozen face just to warm up his lips enough to move.

It was fire and ice for Caviezel, culminating in one of the most literally shocking moments on the set when both Caviezel and assistant director Jan Michelini were struck by lightning while shooting in the midst of a thunderstorm. The bolt went right through Michelini’s umbrella and zapped Caviezel as well. Astonishingly, neither man was seriously injured.

The toll of physical and mental stress on Caviezel continued to build through the production. The actor suffered a lung infection at one point and an excruciating shoulder dislocation, as well as numerous cuts and bruises. “But if I hadn’t gone through all that, the suffering would never have been authentic,” Caviezel comments, “so it had to be done”.

There were also unexpected psychological, and spiritual, challenges. “It was bizarre,” he admits. “I was thinking I’m just an actor playing a role but I also began to see that this couldn’t be just another role. I had no idea how much I would have to pray during this film to keep things in perspective”.

Ultimately, Caviezel feels he learned many vital lessons. “The role changed my life in the sense that now I’m no longer afraid of doing the right thing”, he explains. “I’m now more afraid of not doing the right thing”.

To play Mary, the mother of Jesus, Gibson went farther afield, choosing Maia Morgenstern, a renowned Romanian actress of Jewish descent. Gibson had viewed Morgenstern in a decade-old European movie and upon seeing the tenderness in her face, immediately thought of her for the role. With little else to go on, he set out on a quest to meet her, discovering she is considered one of the greatest actresses of her generation in her country.

Morgenstern says taking the role “wasn’t so much a choice as recognizing a real chance in my life to do something important, to have a unique life experience”. To gain a greater understanding of Mary, Morgenstern scoured paintings, sculptures and literature for portraits. “I was very inspired by art in my preparation”, she says, “because seeing Mary in so many different ways, I opened myself up to see what emotions came to my soul”. She also read the script more than 200 times to make the story an integral part of her own fabric ‘ and she found great meaning in scenes that reveal Mary’s affectionate and joyful relationship with Jesus before these events.

As she meditated upon the nature of Mary, Morgenstern began to see the character on a larger level. “Capturing Mary for me was about understanding a way of life, about how someone transcends pain and suffering, and turns it into love”, she explains. “I believe it is the most painful thing imaginable to see your son wounded as Mary does, to lose your child as Mary does, but all she can do is keep loving and trusting and try to use all the compassion in her heart. That is what I wanted to get across on the screen”. In an interesting twist, Morgenstern was herself pregnant while playing the role, giving her further inspiration into exploring the depths of maternal love.

Morgenstern also sees the film as having real relevance to modern audiences, regardless of their religious background. “The beauty of the movie for me is that it speaks so powerfully about humanity, and also the lack of humanity that has caused us to continue killing one another for the last 2000 years”, she observes. “These are very important things to think about”.

Also immersing herself into the life of a woman beloved through the centuries is international film star Monica Bellucci (The Matrix series) who portrays Mary Magdalene. When Bellucci heard that Mel Gibson was making a film about The Passion, she was so intrigued by it, she immediately pursued him. “I thought it was such a strong and courageous project to take on”, she explains. “I knew it would not be an easy movie, but it is also the kind of movie that you know audiences are going to think about for a long time afterwards. This is what drew my interest”.

After meeting with Gibson, he cast her as Mary Magdalene, which thrilled Bellucci. She comments: “I wanted to play Mary Magdalene because for me she is so human. When Jesus saves her it’s as if he makes her aware of her own worth as a human being, and for the first time she experiences a man looking at her in a different way. To me, she is a woman who gets to know herself and finds a better person than she ever thought she could be”.

Learning Aramaic came almost naturally to Bellucci. “Maybe it is because I am Italian, but for me it felt very familiar and very beautiful,” she says. “But even though we spent so much time learning Aramaic, I think of the film almost as a silent film because we went deeper than language in the performances”.

On the set, Bellucci was impressed not only by the devotion of the cast, but by the wide range of cultures and beliefs she encountered. “What I liked is that even though this is a movie about the life and death of Jesus, there were people from everywhere, every religion, every background, all together working on creating this one film. Not just as an actress, but as a human being, this was a great experience”.

She also found a real affinity with Mel Gibson’s directorial style. “He’s a very instinctive director”, she comments. “He doesn’t talk a lot but it is as if he can tell you more things with his body and mannerisms than with talk. Of course, he’s very intelligent, but he also feels things very quickly and deeply and to me, this is very important for a director”.

The Passion of the Christ (2004)

Directed by: Mel Gibson

Starring: Jim Caviezel, Maia Morgenstern, Monica Bellucci, Mattia Sbragia, Hristo Shopov, Claudia Gerini, Maia Morgenstern, Francesco De Vito, Luca Lionello, Fabio Sartor

Screenplay by: Enzo Sisti, Mel Gibson, Steve McEveety

Production Design by: Francesco Frigeri

Cinematography by: Caleb Deschanel

Film Editing by: Steve Mirkovich, John Wright

Costume Design by: Maurizio Millenotti

Set Decoration by: Carlo Gervasi

Art Direction by: Pierfranco Luscrì, Daniela Pareschi, Nazzareno Piana

Music by: John Debney

MPAA Rating: R for sequences of graphic violence.

Distributed by: Newmarket Films

Release Date: February 25, 2004

Views: 153