The Academy Award-winning team of Tom Hanks and director Robert Zemeckis (Forrest Gump, Cast Away) reunite for The Polar Express, an inspiring adventure based on the beloved Caldecott Medal children’s book by Chris Van Allsburg. When a doubting young boy takes an extraordinary train ride to the North Pole, he embarks on a journey of self-discovery that shows him that the wonder of life never fades for those who believe.

Combining classic storytelling with cutting-edge filmmaking, The Polar Express debuts a highly advanced version of motion capture technology developed and tailored to meet Zemeckis’ uncompromising vision and is the first feature ever to be shot entirely in this format.

For nearly 20 years, families around the world have made Chris Van Allsburg’s enchanting story The Polar Express part of their holiday celebrations, as much a treasured part of the season as hanging stockings by the fire, exchanging warm wishes and coming together with friends and family.

“It became an annual tradition to read the story to my son while he was growing up and it never failed to fascinate him,” says filmmaker Robert Zemeckis, a fan of the book since its 1985 publication. “The imagery has an otherworldly quality, existing somewhere between dreams and reality, which captures the mystery of a restless Christmas eve.”

“There was a visceral element to the story, I hoped would find its voice for the screen,” adds Tom Hanks, himself a father of four who has logged countless bedtime story hours of his own. “For years, between November and December, depending on the children’s ages,” he recalls, “I think I read it four times a week, twice a night, over and over again. So I’ve been aware of the story since my 14-year-old was three.”

He and Playtone partner, producer Gary Goetzman, proposed the idea of a big screen version to author Van Allsburg and producer William Teitler, partners in Golden Mean Productions, and Hanks ultimately brought the project to longtime friend and colleague Zemeckis. Together, the Oscar-winning pair had previously explored issues of the human spirit in Forrest Gump and Cast Away. Both were intrigued by the important spiritual journey taken by the nameless young hero in The Polar Express.

Beloved by children, the The Polar Express holds a special appeal for adults as well, who see themselves in the character of the young boy and remember their own childhood excitement and anticipation on that one most important night of the year. Perhaps they also remember the moment when the first shadowy doubts crept into their own young hearts and they realized that growing up might mean losing something precious and intangible forever, something they couldn’t quite define but they could certainly feel.

The Polar Express is about that moment, that crucial juncture of innocence and maturity where a child can choose one path that will close his heart forever or another, where he learns that faith has no age, no rules and no limits.

“The book took me distinctly into what I call the ‘waking space,’ that state of mind between sleeping and waking where you have a touchstone in reality but are still seeing through a dreamlike filter and you’re vulnerable to a lot of emotions that wash over you,” says producer Steve Starkey, Zemeckis’ longtime producing partner and an Oscar winner for his work on Forrest Gump. “I said to Bob, ‘this is a place worth transporting people to.’”

Zemeckis, who wrote the screenplay with William Broyles, Jr. (Cast Away, Apollo 13) and went on to direct The Polar Express, acknowledges that, “It’s a story everyone can relate to. So many of us, as children or adults, have questioned our belief in something or gone through the process of having our faith tested and restored. Kids can take the story literally as a journey to find Santa Claus, while older readers understand it as a metaphor for much bigger ideas. It deals with the symbols of Christmas but at its core is a universal story about belief in things you don’t completely see or understand.

“Hopefully,” the director continues, “as you grow older you don’t become so cynical that you stop believing. The idea of Christmas is warmth and unselfishness. Santa Claus is a symbol of that but you don’t have to believe in him to have that feeling.”

Once on the train, the boy meets a number of other children, each with his or her own circumstances and lessons to learn. “Much like The Wizard of Oz,” notes executive producer Jack Rapke, “each child aboard this magic train is on his or her own personal journey, and each must find what they’re missing to make themselves complete. There’s a girl who has all the talent, spirit and intelligence to be a good leader but she lacks confidence, a know-it-all character who lacks humility and another boy we call Lonely Boy, who grew up in a loveless environment and needs to have faith in other people. These rich themes play out on an inner, character level while simultaneously there’s the tremendous spectacle of the outer journey as the train speeds towards the North Pole.”

Author and artist Chris Van Allsburg, one of the most respected names in children’s literature, earned a 1986 Caldecott Medal for the oil pastel drawings that illustrate The Polar Express. Noted for his imaginative and original tales, Van Allsburg began his publishing career with The Garden of Abdul Gasazi in 1979, which drew unprecedented praise and a Caldecott Honor Award, a rare achievement for a debut publication. He followed that with the fanciful Jumanji, in 1981 (the source for the 1995 feature film starring Robin Williams) and The Polar Express in 1985 – both of them Caldecott Medal winners, placing Van Allsburg among a small group of authors who have earned that coveted award twice.

“Lucky are the children who know there’s a jolly fat man in a red suit who pilots a flying sleigh,” says Van Allsburg, who likewise credit grown-ups who manage to cross into adulthood without jettisoning their sense of wonder. “We should envy them. The inclination to believe in the fantastic may strike some as a failure in logic, or even gullibility, but it’s really a gift. A world that might have Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster is clearly superior to one that definitely does not.”

Creating a Visual Landscape as Magical as the Story Itself

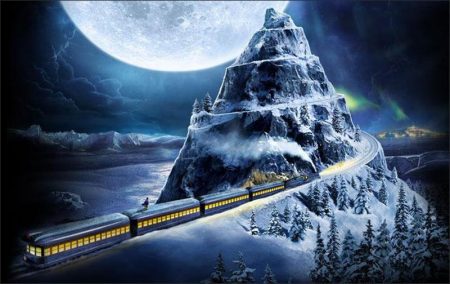

Zemeckis was equally captivated by the book’s rich and sensitively rendered illustrations. Genuine warmth emanates from the faces of the children in the cozy Polar Express train compartment while, outside, the ever-changing landscape appears simultaneously mysterious and inviting with its deep, dark forests and snowy mountains.

“Chris’s illustrations are honest and familiar and at the same time wonderfully transcendent,” notes Zemeckis, who sought to recreate that quality on the screen, offering audiences a chance to experience what a midnight trip to The North Pole might look like through the eyes of a young boy. “It’s easy to see yourself, your children, or the kids you grew up with in the faces and personalities of these characters, and the landscape that the train passes through is like the dreams we all had about distant places where magical and exciting things could happen.”

“There’s something absolutely haunting about his artwork,” Hanks describes. “It has a tactile feeling that’s really the emotion he communicates through the artwork itself. When he’s talking about the little boy lying quietly in bed, the picture really gives you the sense of it. When the train pulls up on his front lawn you can hear the chugging and the steam.” As he recalls, he and Zemeckis agreed it would be a good idea “to recreate each painting in the book at some point throughout the movie. We might create an elegant film that would present the Christmas spirit in a brand new way.”

Adds Zemeckis, “We wanted to offer the beauty and richness of Chris’ illustrations from the book as if it were a moving oil painting, with all the warmth, immediacy and subtleties of a human performance.”

But how? Not only would a live action film of such far-reaching landscapes be staggeringly impractical if not impossible, it would lack the luminous texture the filmmakers were committed to recreating. Another possible option – animation – had its own limitations. “The problem with traditional animation for a project like this,” says Zemeckis, who isn’t averse to employing the technique in its rightful place, “is that it falls short in depicting authentic human characters. With exaggerated images, fantasies like Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, or cartoons, it’s great. But I was looking for something more realistically alive.”

Zemeckis presented his unique challenge to visual effects wizard Ken Ralston, a multiple Academy Award-winner for his work and currently a senior visual effects supervisor at Sony Pictures Imageworks, an industry leader in digital production. Ralston dates his creative collaboration with Zemeckis back to the 1985 sci fi comedy adventure Back to the Future, a film remembered as much for its heart and deft storytelling as for its dazzling special effects.

Raltson proposed motion capture, a process by which an actor’s live performance is digitally captured by computerized cameras and becomes a human blueprint for creating virtual characters. Zemeckis was familiar with the technique but would not have expected it to serve his purposes for The Polar Express, based on applications he had seen. But this was no ordinary mo-cap his friend had in mind. It would have to be a giant step beyond current standards in order to achieve the depth and visual complexity Zemeckis required.

Coincidentally, Ralston and his Imageworks colleague, visual effects supervisor Jerome Chen, had been doing preliminary work on just such an advanced process, to be the next generation of mo-cap, far more sophisticated than anything ever seen before. Beyond mere motion, this highly developed system was designed to capture every discernable movement and the subtlety of human expression from an actor’s performance, down to the slightest nuance or flutter of an eyelid. Additionally, unlike existing mo-cap systems that are limited in range, it could simultaneously record 3-dimensional, high-fidelity facial and body movements from multiple actors, through a system of digital cameras providing a full 360 degrees of coverage.

Working together, the Polar and Imageworks teams ran a practical test of the process, using Tom Hanks as their first subject.

“I didn’t know anything about this,” Zemeckis says of the groundbreaking process, which they ultimately – and appropriately – christened Performance Capture. “When we did the test and the results came back, it turned out to be the perfect way to do The Polar Express.

“In fact,” he admits, “if this hadn’t been possible, or hadn’t evolved to this degree, I likely would not have moved forward with the project.”

Here was a way – the only way – to achieve the oil painting imagery from Van Allsburg’s drawings onscreen while maintaining the immediacy of real human performances. As Ralston describes it, “Performance Capture offers a vivid rendering of the Van Allsburg world while infusing a sense of heightened realism into the performances. It’s like putting the soul of a live person into a virtual character.”

The process not only exponentially increases the amount of live material that can be captured and interpreted digitally, it also provides unparalleled versatility in the director’s storytelling choices. While traditional film editing is dependent upon the range of coverage or angles from which scenes are photographed during production, Performance Capture technology offered full, limitless coverage that allowed Zemeckis to literally create custom shots during the editing process. He could select from a range of depths and perspectives and move characters in relationship to their cyber surroundings to emphasize nuances of expression or other details, all with natural camera movements. The oil painting effect, so essential to Zemeckis, would be enhanced in layers during the post-performance phase, through state-of-the-art CG rendering.

The Polar Express is the first feature film to be shot entirely in Performance Capture. Those who have seen the final footage attest that it defies easy categorization. Familiar comparisons fall short of the mark. Often it’s described in terms of what it is not – as in not traditional animation, not merely motion capture and not strictly live action. An art form in its own right, Performance Capture effectively breaks new ground to offer images like nothing seen before.

Never one to introduce a new technique on screen for its own sake, Zemeckis can look back upon a filmmaking career marked by many striking innovations, secure in the knowledge that each and every time he broke creative ground it was in service to a story.

In Forrest Gump, for example, Tom Hanks as the fictional Gump casually and seamlessly turns up in authentic archival footage where he is seen interacting with historic figures such as President Kennedy. Recalling that startling effect, Zemeckis now says, matter-of-factly, “Well, we had a story about a guy who had met presidents. It was in the script. It was assumed that he would be on film at these meetings so we took news footage of real presidential appearances and then figured out a way, with the computer, to do it. “It’s easy to do that kind of thing now,” he admits. “But then, it was tough.”

Prior to Forrest Gump, Zemeckis charmed audiences with a lively blend of live action and manic animation in the 1988 classic action comedy Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, another fresh use of technology that the director simply acknowledges as a case of “using the modern tools we had to integrate a 2-dimensional cartoon character into a 3-dimensional world.”

“Bob will make a movie to test the art form, or to wrestle with some aspect of emotion or human nature,” says Hanks. “He doesn’t take his job lightly. He’s interested in making films that somehow break a mold or challenge not only himself as a filmmaker but the entire motion picture oeuvre in some way.”

What matters most is telling a story in the best way possible. Essentially, Zemeckis believes, either with or without cutting-edge effects, “the entire spectacle of cinema is illusion. Even the most basic techniques are illusion – a cut, a close-up, it’s all fake. It’s magic. It doesn’t exist in real life. So, if you look at it that way, all movies are illusions anyway, and some of the things I do are just extensions of that. That’s what’s so much fun about being a movie director.”

The Polar Express (2004)

Directed by: Robert Zemeckis

Starring: Tom Hanks, Daryl Sabara, Nona Gaye, Jimmy Bennett, Eddie Deezen, Michael Jeter, Brendan King, Andy Pellick, Mark Goodman, Rolandas Hendricks, Gregory Gast

Screenplay by: Robert Zemeckis, William Broyles Jr.

Production Design by: Rick Carter, Doug Chiang

Cinematography by: Don Burgess, Robert Presley

Film Editing by: R. Orlando Duenas, Jeremiah O’Driscoll

Costume Design by: Joanna Johnston

Set Decoration by: Karen O’Hara

Music by: Alan Silvestri

MPAA Rating: G for general audience.

Distributed by: Warner Bros. Pictures

Release Date: November 10, 2004

Views: 105